The second female director of the Kunstverein Munich—one of Germany’s oldest art institutions—reflects on her diverse career, the importance of paying fair wages, and ensuring art institutions don’t reproduce the systems they are criticising in their exhibitions.

Unlike many of her contemporaries in the art world, curator Maurin Dietrich spent little time in galleries and museums as a child. She attributes this to her non-academic background. “Art institutions are historically intertwined with the bourgeoisie and that still bears traces today. At least in the German context, it is an urgent task to become more inclusive, not only in terms of race and sexuality, but in terms of class identities as well.”

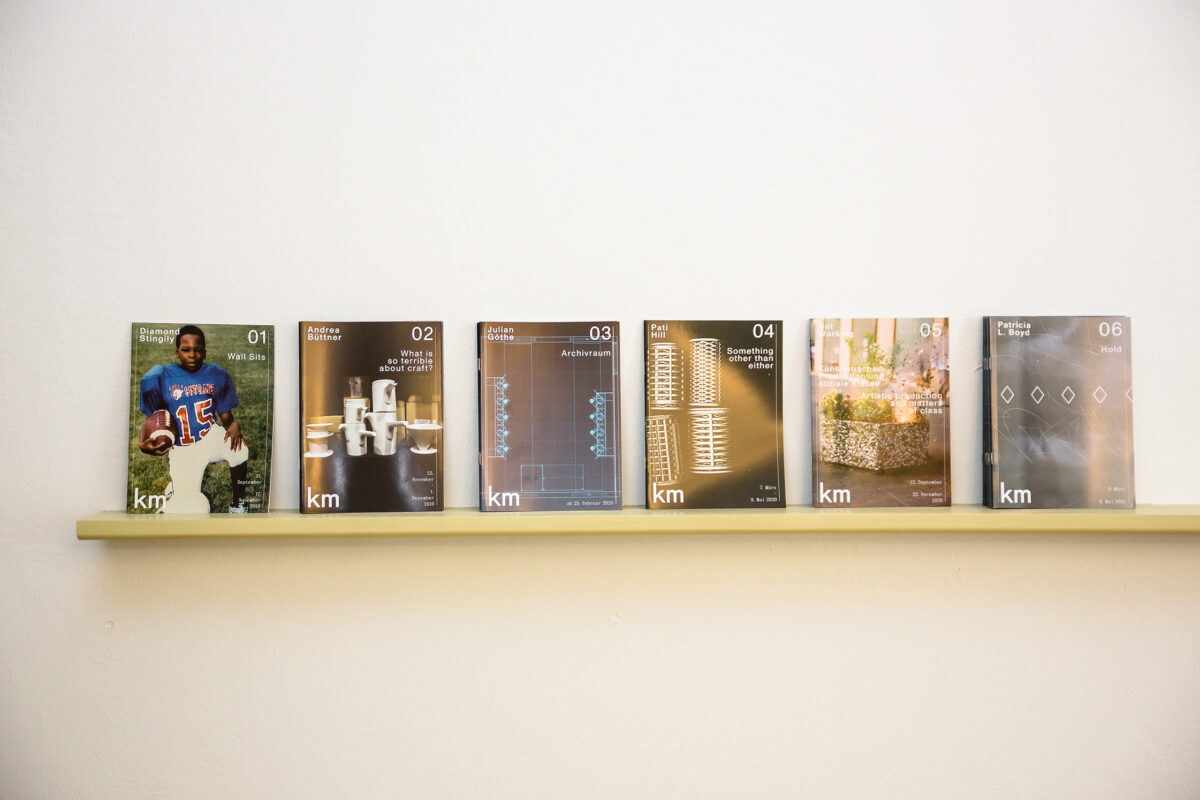

In contrast, Dietrich’s introduction to the visual art world was by way of reading, writing, and storytelling. Spending hours in her local library from a young age, Dietrich went on to study comparative literature and art history at The Free University of Berlin. “The ways we tell stories about the world to each other and to ourselves, and how these serve as an identity construct, have been a recurring interest for me. Most of the artists I find myself interested in come from writing and have moved to visual art practices a lot later in their lives,” she explains, citing US-American writer and photocopy artist Patti Hill and New York-based artist and poet Diamond Stingily as examples with which she both worked.

While studying, Dietrich was surrounded by books both in and out of university: she spent most of her free time working part-time jobs, taking coats at the Berlin State Opera, doing night shifts at the academy of arts and eventually working at publishing house and art bookshop Walther König’s main Berlin store. “It was an essential part of my education. I often had hours during which no one would come by. I would take the time to read and look at expensive publications,” she says. “I also just needed to make money. From the beginning of my degree I wasn’t sure if I had the resources to actually make it in the art field.”

During this time, Dietrich also undertook a variety of unpaid internships, including a stint at organising residencies for Middle Eastern artists traveling between Tel Aviv and Berlin on a regular basis. Upon completing her studies, Dietrich was hired at Berlin’s renowned KW Institute of Contemporary Art. “I could do what I loved and make the rent, so it was a really important moment for me.” Starting out as a project assistant, before working her way up to the position of curator, Dietrich—along with her fellow curator Cathrin Mayer—began to question how she could open up the spaces of KW to make the community surrounding it feel part of the institution.“When you’re at the very beginning of your artistic practice it’s not like you’re immediately invited to have a solo show at KW. So, I wondered, what could be people’s way in?” She was also interested in finding a way of bringing life (and nightlife in particular) back to the area around the institution, located just off Berlin Mitte’s famous Auguststrasse. While stretching across the city centre and being full of other contemporary art galleries, the street is “heavily gentrified”. “It feels like a film set. You’re literally in the middle of Berlin, but if you’re there after 10:00pm you feel like you’re the only person out there.”

The outcome of these ruminations was Pogo Bar, a regular show, taking place every week in KW’s basement bar to present new performance commissions by young artists. “It felt like the underbelly of the official program. It was the exact opposite of the white cube setting upstairs and held so much warmth and intimacy,” says Dietrich. The curators and bartender Neda Sanai even asked each of the artists who performed there to devise their own cocktail as part of their work. For example, Croatian spoken word artist Nora Turato, who delivered her first performance outside of Amsterdam at Pogo Bar, came up with a twist on a Bellini. Considering that Pogo Bar was the first stop on many artists’—such as Turato’s—road to recognition, it seems strange that all the performances there went largely undocumented. But according to Dietrich, “this was the beauty of it, it was transitory, ephemeral. There were hardly any images taken: you were either there that evening, or you weren’t.”

Similar questions and motivations triggered Dietrich to set up her own project space andsmall residency, Fragile, in collaboration with the artist Jonas Wendelinat Leipzigerstrasse. “More and more, I got the feeling that I wanted to create a space in which to put on shows by artists who didn’t necessarily want to have the pressure of a big institution, such as KW, behind them.” Fragile developed organically over years of conversation with Jonas Wendelin and eventually opened its doors with a performance by the musician Sophie on the hottest summer day of 2018.Sophie—who tragically died last year—,“opened the space with a musical performance exploring ideas around the notion of “Klangkörper”—a room that is needed in order to produce sound.” Fragile went on to present solo exhibitions by artists such as Sean Mullins, Sung Tieu, Analisa Teachworth, Dese Escobar, Kandis Williams, or chef/artist Caique Tizzi, who transformed the space into a kitchen from which to serve food all night.

Looking back at this “intense” time, working at KW, running Fragile, as well as other curatorial projects on the side—such as mentoring at the Berlin Programme for Artists upon invitation from her friends Simon Denny and Willem de Rooij—Dietrich is unsure as to how she managed to juggle all her commitments. “I think I just never really slept much during those years,’ she says, laughing. “Now most of my friends make fun of me because my favourite hobby is sleeping. Maybe I just have some sleep to catch up on.”

In her current position as the Director of Kunstverein Munich, one of Germany’s oldest art institutions, however, there is little time to catch up on sleep. “Kunstverein Munich has a really rich history of working with artists at incredibly fragile moments, often very early onin their careers,” says Dietrich. “For this reason, the institution has always resonated with me. But I never dreamt of being able to direct it.” After seeing a job advertisement on E-Flux, however, she felt more than ready to step up to the challenge. “I already had a full programme of what I wanted to do there in my head. So I took some time to write it all down. It felt genuine and wild to imagine the space of Kunstverein as a curatorial home.”

“I would love it if the art world and the cultural sector in general could become more inclusive, not only in terms of race and sexuality, but in terms of class identities as well.”

Taking the reins of the institution in 2019, Dietrich is only the second female director in the history of the Kunstverein. When asked if championing women in the art world is one of her ambitions as director—under her leadership the institution has predominantly shown work by female artists, theorists, and writers—she says that “our intention is not to amplify female voices alone. Rather, Gloria Hasnay(the curator)—,Gina Merz (the assistant curator),and I talk about practices that we find urgent, and most of these just end up being “non-male.”

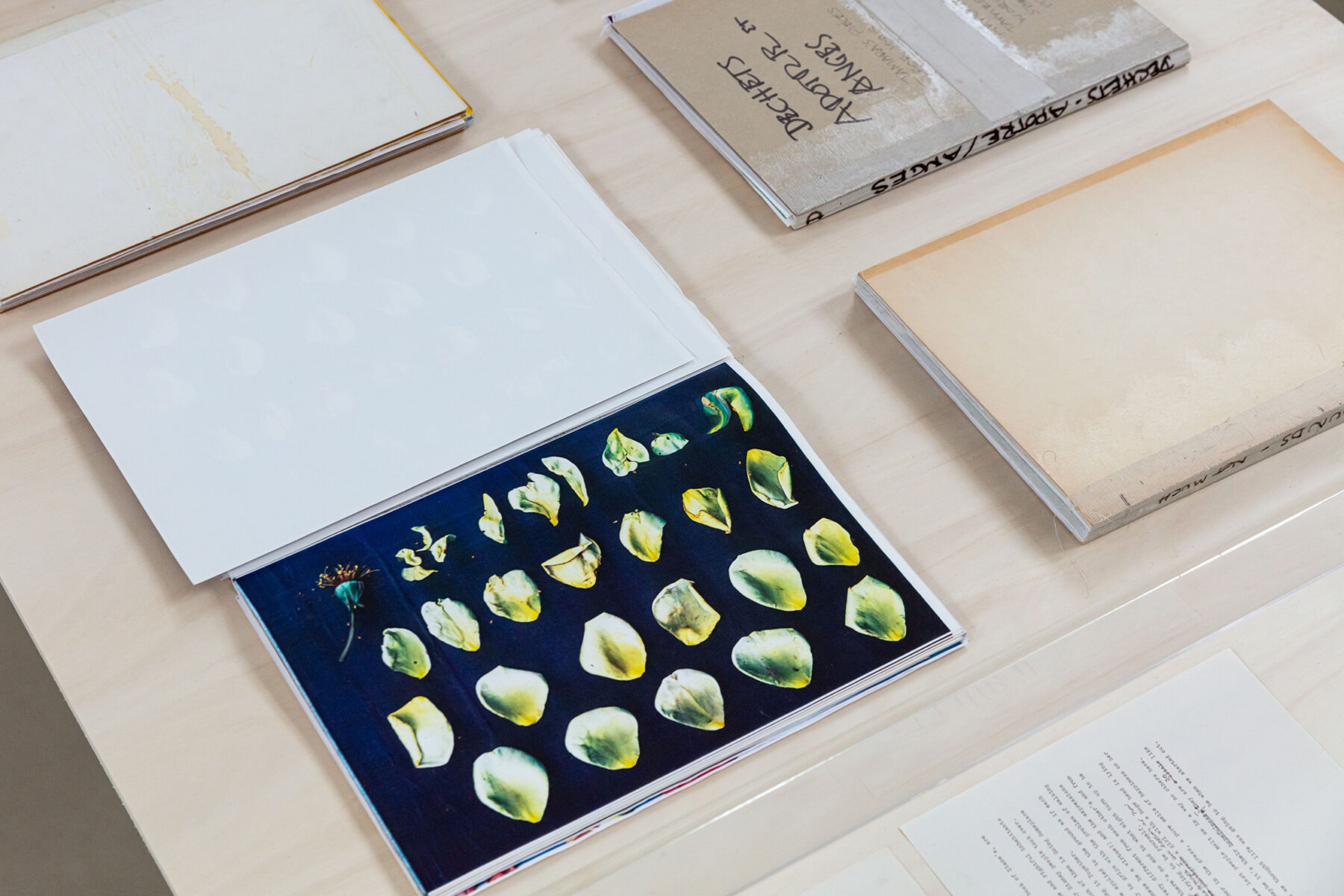

During her tenure, Dietrich wants to achieve many other things. She has already made structural changes, including cutting down the Kunstverein’s programme from six to four shows per year. “This has meant higher production fees and better payment for everyone involved. It has also allowed us to do more publishing work.” Paying fair wages is particularly important in the context of Munich: the rising costs of living makes it extremely difficult for artists and cultural workers to remain in the city. “Munich is not so much a space for production, it’s a space for presentation. Artists are struggling to afford studio spaces,” says Dietrich.

“We were aware that if we were doing a show questioning the concept of class, we couldn’t just reproduce the mechanisms that we were trying to address.”

This being said, the city has a “very supportive art scene. I’m surrounded by incredibly smart colleagues from other institutions”—in this connection Dietrich mentions Andrea Lissoni who went from working at Tate to directing Haus der Kunst—“who I’m constantly in conversation with. Everyone of us knows that we are utterly dependent on each other.” Dietrich is also trying to help redistribute resources in the city. “There are loads of people here that have the assets we need.” For example, over dinnertime conversations, she has managed to convince the owners of a property located at a nearby lake to open it up for 20 artists to live and work there. She also set up writers residencies aimed at authors and critics, as well as artists whose practice is based on writing, at a villa at Lake Starnberg.The intention is to approach fiction and narration outside of traditional exhibition spaces. Central to the residency is having time and space to write—an activity that is often inadequately remunerated and too rarely adressed by funding programs within the art context. “We think about the writers’ residency in the context of curation, which derives from the Latin word curare, which means to look after, to care for, and was originally used in relation to objects, but over time became associated with people and hospitality.”

These topics not only permeate the Kunstverein’s operations: Dietrich also placed them front and center in the institution’s 2020 show Not Working, which explored questions of class and artistic production. “The topic has been so heavily overlooked. It felt so incredible and urgent to do this project in Munich’s context, but it has also been a way of coming to terms with my own background.”

Bringing together international artists, theorists, and writers—including Angharad Williams, Annette Wehrmann, Gili Tal, Ramaya Tegegne, Marina Vishmidt and Lise Soskolne to name a few—who examined the interdependence between artistic production and social class through their work, the exhibition was accompanied by film and discussion programs, as well as a publication going even deeper into its themes. “If any of the artists who were contributing artwork also wanted to be part of other areas of the project, we made sure that they would get another fee on top,” says Dietrich, circling back to the topic of fair wages. “We were aware that in questioning the concept of class, we couldn’t just reproduce the precarious mechanisms that we were trying to address. Thankfully, we got a substantial grant from the German cultural foundation that made it possible. We were transparent with the artists and told them that if we didn’t get the money, we wouldn’t go through with the project. We really wanted to be able to pay €1,000 for a text and didn’t want anyone to have to work for free.”

“Everyone of us knows that we are utterly dependent on each other”

In 2023, Kunstverein Munchen will celebrate its 200th anniversary. “From the beginning I knew that this anniversary would fall into the period that me and my team would be directing the institution,” says Dietrich. “At first, I was only sure of what I did not want: making a coffee table book that no one would ever use or live with in any meaningful way.” Instead, she decided to distribute the budget over three years, and also hired an archivist full time to delve into the history of the institution. “We aren’t simply looking at the documents that are already in the archive, but also at what isn’t there and at what should be.”

In the lead-up to the bicentennial anniversary Dietrich also commissioned the artist Julian Göthe to conceive an installation that draws on the building’s architecture and the history of the Kunstverein’s program. Now the archive space includes a room designated to preserving, examining, and understanding the institution’s history, while making space for public formats which are conceived in collaboration with archivists, art historians, and artists. Considering Dietrich got into visual art through literature and storytelling, it feels fitting that she is now passionate about using her position as a way of drawing attention to untold stories. We can’t wait to hear more of her activities and plans for the Kunstverein in the future.

Maurin Dietrich is the current director of Kunstverein Munchen, one of Germany’s oldest art associations. She previously worked as a curator at KW in Berlin, and ran her own gallery space, Fragile. If you would like to find out more about her work follow the Kunstverein on Instagram or check out their website. Or, if you’d like to read more stories about the German art scene, why not take a look at this profile of Berlin-based auction house CEO Diandra Donecker, or this interview with Sarah Haugeneder, a board member of Munich-based art initiative Various Others.

Interview: Emily May

Photography: Manuel Nieberle