For years Florian Holzherr has photographed not only the buildings of the most important architects in the world, but also for renowned international artists. He’s collaborated intensively with James Turrell, for whom he frequently photographed the Roden Crater – a spectacular sky and light observatory in the Arizona desert.

Privately, the Munich native has fulfilled a very special dream. Specifically, that the architect Andreas Meck created a futuristic workroom for him in his garden.

In the interview, the 44-year-old architectural photographer explains why artists don’t have friends and that he would never trade places with a fashion photographer.

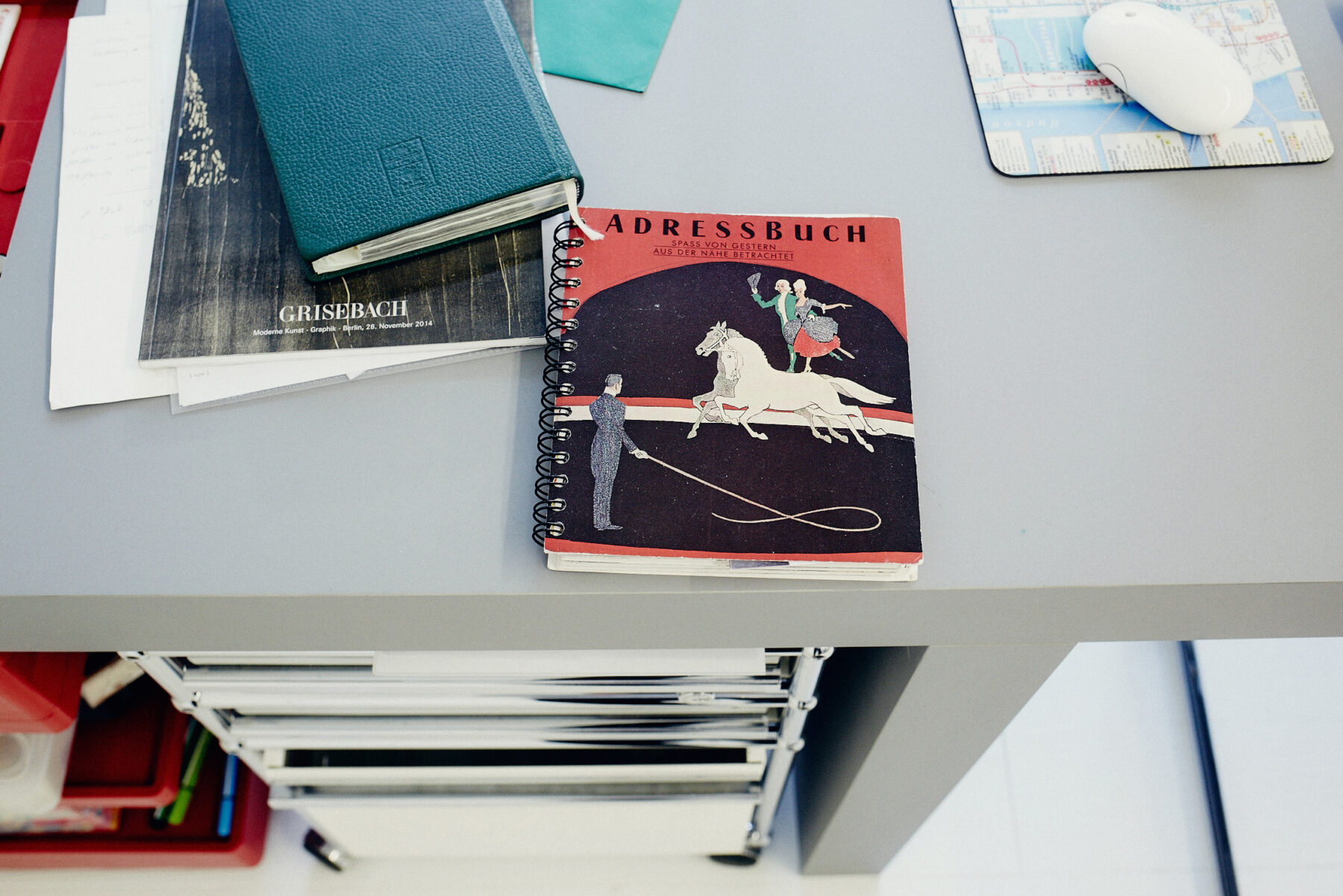

This portrait is produced together with USM and is part of the series “Personalities by USM.” See a different angle to this story with an interior focus here.

-

Florian, you’re often in New York and Los Angeles as well as in the deserts of the US. What takes you there?

My collaborations with Donald Judd and the land artist James Turrell. From 2000 to 2008 I was frequently in Marfa, Texas for the Judd Foundation. Very impressive! I’m always going back to Flagstaff, Arizona because Turrell has his crater there – the Roden Crater, an extinct volcano, which Turrell has developed over the last 40 years as a spectacular sky and light observatory. I really do a lot of photography for him. All of the artists that I think are amazing, are in the desert, like Michael Heizer and Walter de Maria, who unfortunately died in 2013. All of them realized huge projects in different states.

-

Did you ever think about just completely moving to the US?

Yes, in 2003, but then I met my wife and I stayed here. New York is wonderful, but if you really need to live there, it’s insanely difficult, brutal and expensive. You won’t live in Manhattan or Queens, but somewhere outside. You have a certain advantage when you go from Germany to the US as a photographer. Americans love “Made in Germany” photography.

-

What do Americans associate with the label of “German photographer?”

Quality. Unobtrusiveness. A different way of photographing. The American architecture photography is partially super-kitsch and colorful. In Germany the photography is drier.

-

Let’s look into the past. How did you become a photographer?

There were always three things that interested me: art, architecture and photography. I’m not an artist, because the idea has to stem from you. I was scared stiff of becoming an architect and in hindsight, I have to say: fortunately. What architects have to deal with is awful.

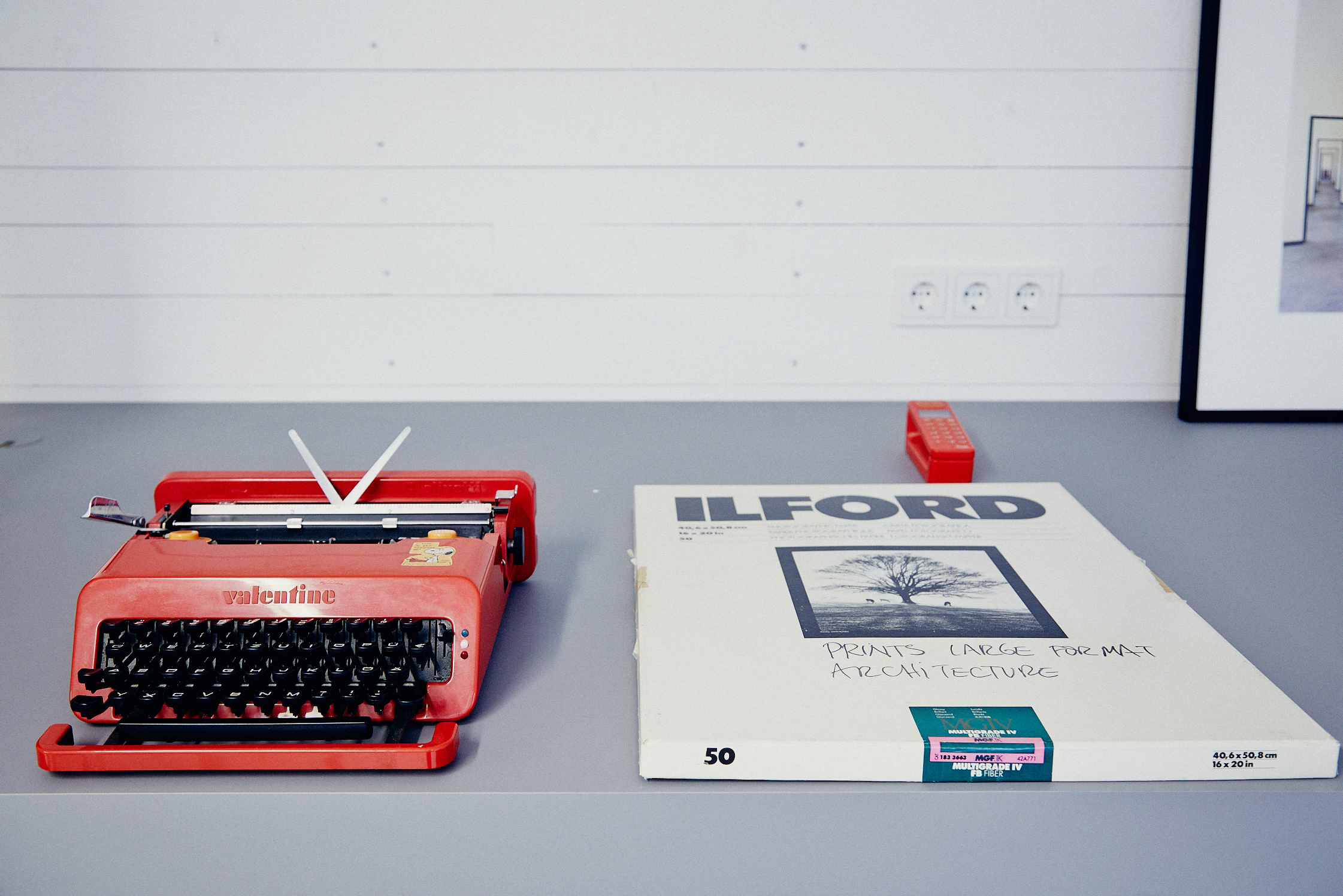

Then I applied to the photography school in Munich. The first time I was rejected. The next year I tried in Zurich, Berlin, Düsseldorf and Munich and was accepted at all of them. At the time, photography school was crazy expensive, because digital photography wasn’t happening yet. You were giving out 500 Euros a month for film and paper. So I finished three years of schooling at the Academy of Photo Design – which is, by the way, the oldest photography school in the world.

-

How did you enter the workforce after school?

Meeting James Turrell in 1989 was really important. At the time he was working in Munich. My sister studied art and was his assistant. Then there was the key experience: at school we were supposed to photograph celebrities. Among others, I sought the architects Herzog & de Meuron, who were not so easy to approach. At some point my phone rang and they said that I could do a portrait of them. I would have 15 minutes. My heart was pounding.

A few weeks after the portrait I was allowed to photograph a house for Herzog & de Meuron. This was a door opener. I always needed a spark. I got to know incredible people: Michael Govan, the director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art – I still work for him. I also work for the foundation of minimalist artist, Dan Flavin, Donald Judd’s Chinati Foundation and the artist James Turrell.

-

What fascinates you about James Turrell?

Turrell is like a polymath from the Baroque era. You can talk to him about raising cattle, because he has 2,000 cows. He has every pilot’s license that there is. He can restore cars. He’s a complete work of art. I spent a lot of time with him in America, and not only for work – we go to breakfast or flying together.

-

So, you would say there’s a real friendship that connects you and Turrell?

Yes, although artist have few friends. It’s always about the project and you can decide if you want to go with them on that journey. Most artists are insane egomaniacs, many aren’t even nice, Dan Favin wasn’t nice, Donald Judd wasn’t nice. Turrell is incredibly nice.

-

Which other artists are friendly?

Ólafur Elíasson. He had a major exhibition in Spain and asked me if I could photograph it. That was really interesting. He’s really easy going, not at all vain. His team is completely professional. You often have to deal with chaotic artists.

-

Is your way of working chaotic?

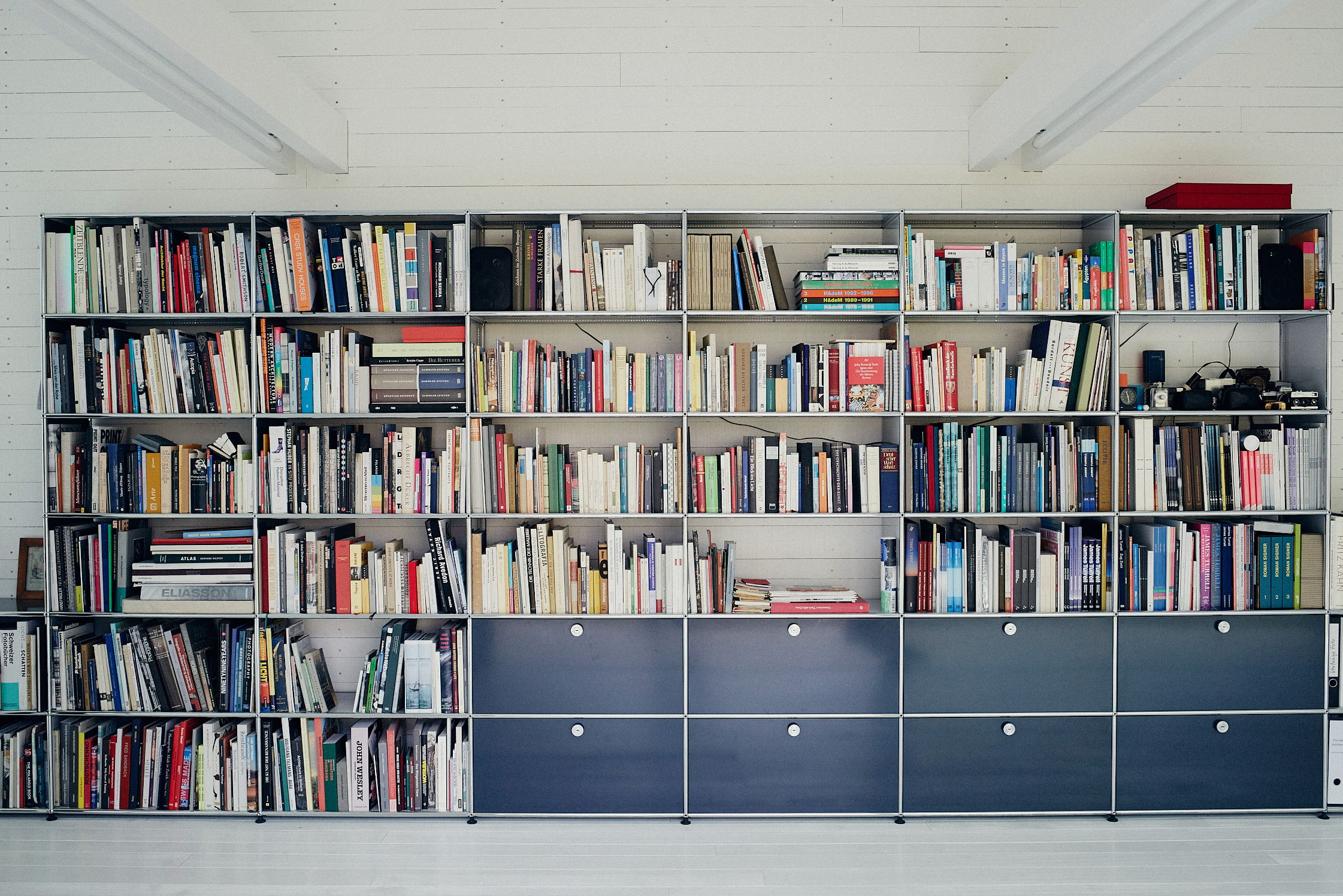

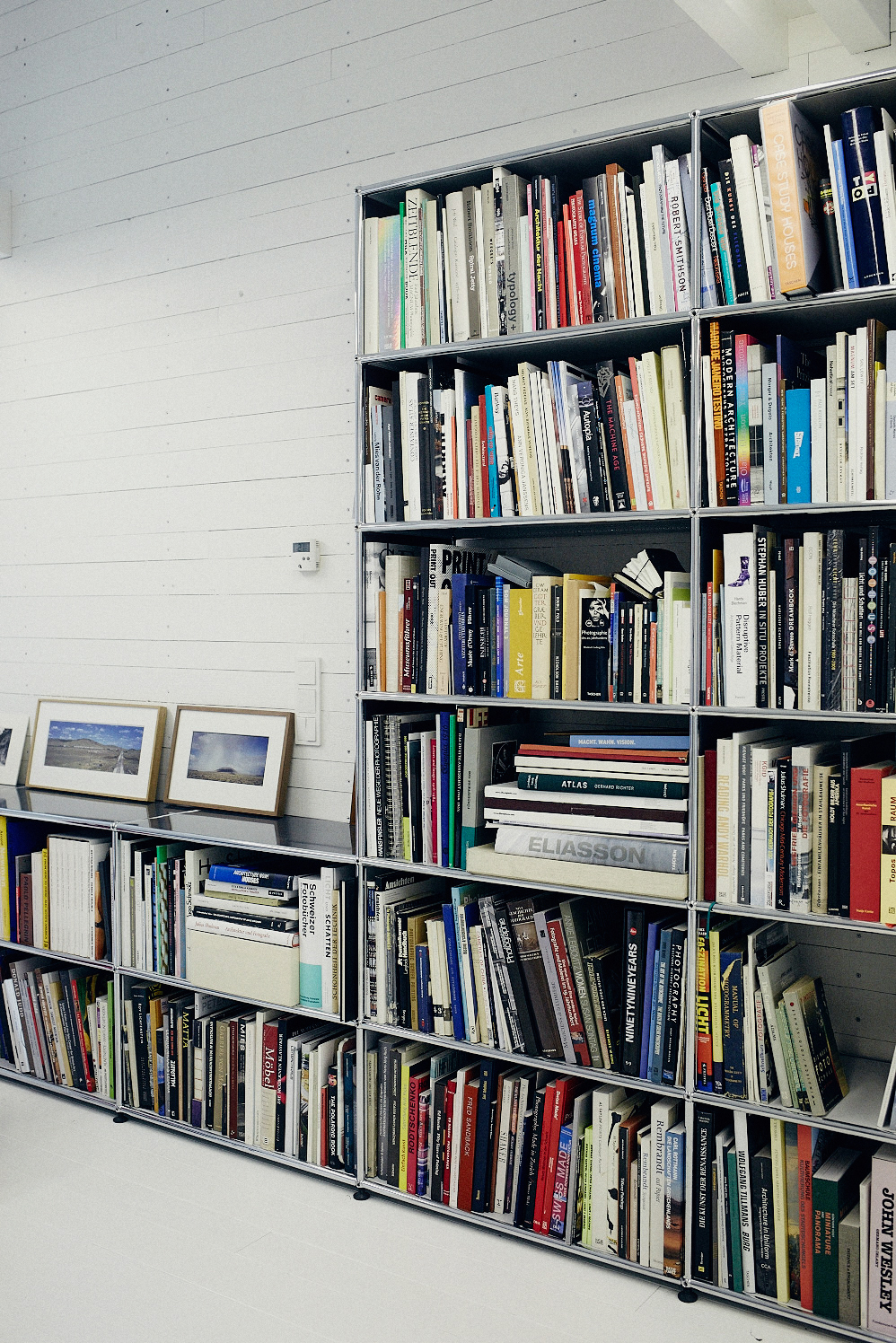

No. Since I’ve had my studio I’m suddenly much more organized than I used to be. This space forces me into order.

-

Could you even work in a place other than your garden house?

If you have something as beautiful as this, you probably can’t work somewhere else. It’s unbelievable how this great space influences my work.

-

How did you get this incredible space?

I always wanted to build something here. And my wife and I needed a place to work. She’s a paper conservator and has her desk here as well. The idea was this: For the architect Andreas Meck. I photographed the memorial for the German armed forces in Berlin. We spent a lot of time together, we were going from Munich to Berlin in the mornings and back in the evenings. That was when I told him about my idea for the garden house. I had no idea if I could afford it.

-

What did Andreas Meck think about building you a garden house?

He was really into it and said that we’d manage it somehow. I didn’t even know if the bank would give me the money. But it worked out. The first draft that Meck made was exactly this house, there were only minimal changes that followed.

-

How would your perfect workspace be visualized?

As a hull for working, where the floor, wall and ceilings were the same. My thoughts were to more or less fill it with my work.

-

Was there an inspiration for the garden house?

“Bor” – a weekend cottage from the 1950s in Sweden. Both have a classic cubature. Marcel Breuer built houses at the same time.

-

You have a pretty impressive collection of cameras. Do you use them all?

In the past, I photographed with all of them. I needed a waterproof camera with which I could photograph my three and a half year old daughter on the beach. The underwater camera from Nikon takes super photos. Another great compact camera is the Rollei 35. The design is incredibly beautiful – a small nice camera that you can just carry in your pocket. But I also take 90 percent of my photos with an iPhone. Everyone makes iPhone photos, it doesn’t matter where you are. Terrible.

-

What annoys you about digital photos?

The quality of photos is usually blurry, which digital cameras don’t do so well. Everyone talks about pixels and sharpness. Really, you have to talk more about blur.

-

You said earlier that you don’t see yourself as an artist – how do you see yourself?

As a craftsman. It’s about making art and architecture look as good as possible. I always tell students, you have to take three steps back. Then you can think about how you photograph something. I find being really creative for me personally is difficult. It shouldn’t be fashionable. My photos have a different validity than images made for Vogue.

-

What distinguishes you from fashion photographers?

As a fashion photographer you can go crazy – so that it cracks just so, because in three months no one is interested anyways. The older it is the more the documentation of art and architecture means because it shows our commonly created history. You have a responsibility to the story. Although this sounds insanely pompous.

-

So you’re not at all interested in portrait or fashion photography?

I like portraits, fashion has never interested me. I have friends that do it on a very high level. But I can’t. Thirty people on set, hundreds of thousands of Euros every day. What happens if you mess up? Oh no. The more peace and time I have, the better I am.

-

What kind of art inspires you?

Minimal Art. Of course Donald Judd. I also treasure Chris Burden. I like artists who have an approach and are manic: so someone like Roman Opalka, who has written a lifetime of numbers. That impressed me. I couldn’t do the same thing for years. Or even Turrell, who’s been working towards one goal for years.

-

Do you have another passion besides photography?

Cars. I drive a 1989 sports car. I’d like a BMW Z1. It’s from 1988, but it doesn’t look old. But now I have a daughter, so there’s no goofing around anymore.

-

To finish, name three buildings that have impressed you.

As a young photo assistant the sports center at Pfaffenholz by Herzog & de Meuron. Then, of course, the Salk Institute in La Jolla in San Diego. The Goetz Collection in Munich, which was the first building by Herzog & de Meuron.

-

And what kind of architecture doesn’t speak to you at all?

The buildings I find difficult are those where all of the fanciness is in the façade but there’s nothing special inside. I could give ten examples, but I shouldn’t say such things publically.

We thank Florian for letting us explore his exceptional world of photography and letting us visit his extraordinary studio.Together with USM we’ve been producing portraits for the Series “Personalities by USM“. Find out more about his interior here. Check out Florian’s impressive architecture shots on his website. In our previous story of the series, we met graffiti artist Andreas Ernst in Freiburg.Browse through all of our stories in Munich.

Interview & Text: Annette Walter

Photography: Conny Mirbach