Finding Martin Rein-Cano isn’t easy – even if you do manage to locate the doorway to his corner building in Prenzlauer Berg, you’ll still see multiple doorbells with his name on them.

Martin created his shared apartment 20 years ago in this historical building in Berlin’s Bötzow district, and the landscape architect has lived within these same four walls ever since. Though there have been a few additions over time – namely, a passageway to the neighboring apartment as well as a small family. Martin’s wife, the composer Rebecca Saunders from London, also has her studio here.

The co-founder and partner of the landscape architecture firm TOPOTEK1, Martin is one of the most important practitioners of his craft in the world. As a company, the self-proclaimed group of “Topotekten” established their office on Sophienstraße once they completed their first work after the fall of the Berlin Wall – today they are working on projects across the globe.

This portrait is produced together with USM for the series “Personalities by USM.” See a different angle to this story with a focus on Martin’s interior here.

“I like to speak about the aesthetic of conflict.”

According to Martin, landscape architects shouldn’t be thought of as fussy mediators. He calls on the profession to do more, and in spite of his peaceful art and friendly demeanor, his work has a penchant for provocation and subversion. That’s why the architect raves about Tempelhof Park and explains that it reminds him of Versailles. He also feels cities are spaces where conflict is cultivated; it’s in cities that Martin locates the challenge for his craft, feeling that conflict should not be ignored or concealed, but rather illuminated.

-

Martin, you’re originally from Argentina – how did you end up in Berlin?

I was born in Buenos Aires and lived there until I was 13. On my father’s side I’m descended from a Jewish-Lithuanian family. My mother was born in Spain. They were both immigrants to Argentina, where, when they were young, they met as members of the Communist Party. Their quasi multi-religious, multi-ethnic marriage only lasted a year. My mother met a German aid worker in Uruguay and fell in love with him, after that we moved to Frankfurt.

-

Why did you choose to study landscape architecture?

I started off studying art history. It was all a bit too dry and academic for me. Then I attended a class on the care of historic gardens, which, at that time, was a relatively new field of study. Through that I traveled to Italian Renaissance gardens and thought it was really cool!

The mother of my girlfriend at the time was a landscape architect, so I learned more about the discipline and transferred to Hannover to study it. I began to live and work in Berlin in 1994 and two years later I founded my own firm

-

How long have you lived in this apartment?

Since 1995. At first it was a shared apartment. At that time, there were still so many apartments to choose from. That was nearly 20 years ago! Soon after that my wife and I took over the neighboring apartment as well. It was empty, so we made a passageway between the two spaces. The previous tenants all moved out, they didn’t like it here. It was quite a deprived area, not at all like Kollwitzplatz. My wife has another apartment in the building where you can find her studio.

-

Do you maintain a strict division between your home and office?

At home I’m with my family for the most part. I don’t work there. But I’m not a strictly creative architect or designer, I’m more of a communicator, an associate designer: I don’t just sit down, sketch something and send it to others to work with. But with cell phones, e-mail and laptops, you’re never really out of the office. In that sense, there isn’t really a clear division. That said, I do find that the intensive design process doesn’t happen at home.

-

Where do you buy your furniture?

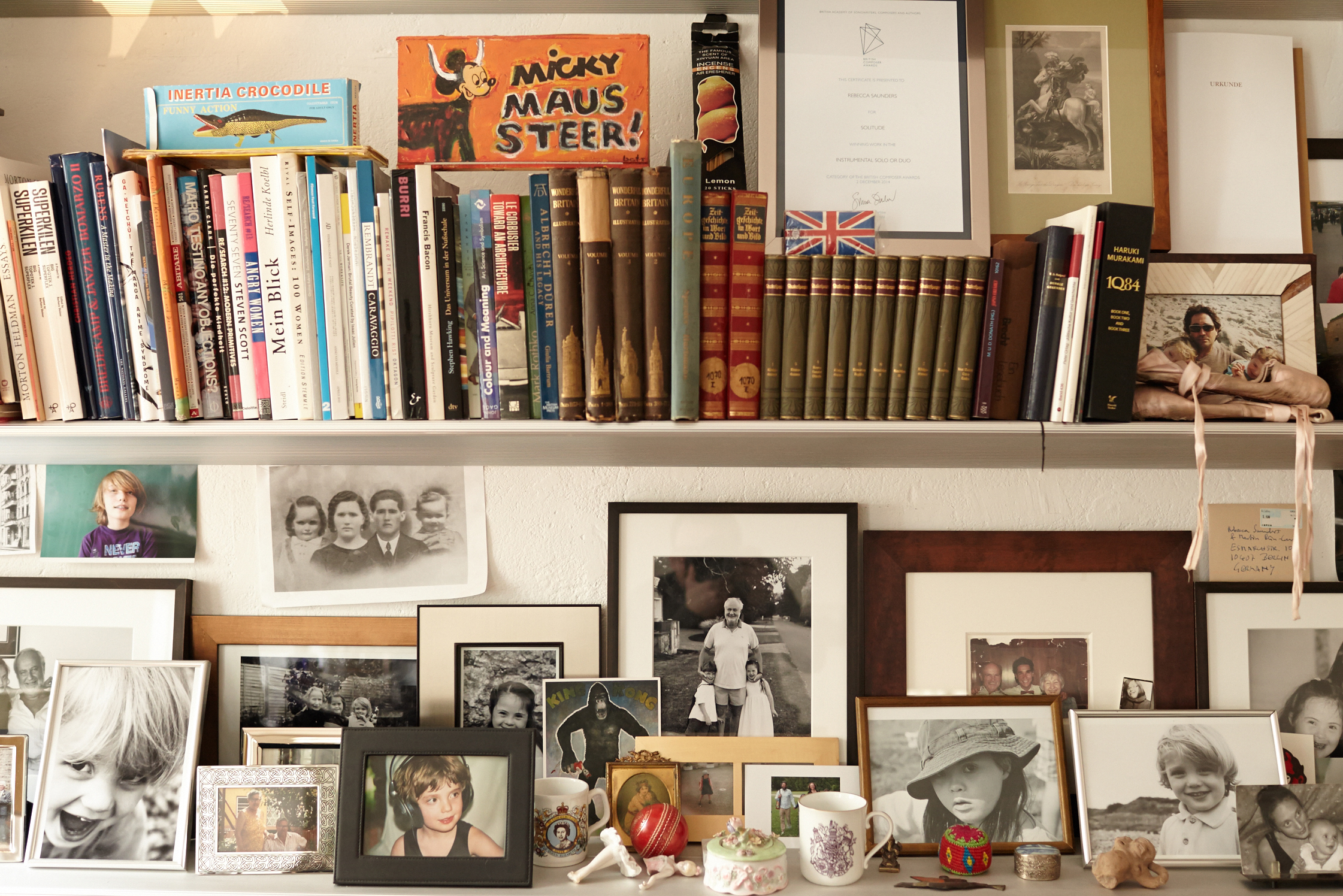

I really like to go to flea markets, but they’re not as fun since the fall of the Wall. The writing desk is from a rummage sale and I found the table set on the street, someone had just thrown it out!

-

Tell me a little about the art in your apartment.

It’s all my friends’ work! For example, Anna Lehmann-Brauns, who is a school friend from Frankfurt, or Martin Liebscher, whose work also hangs in the Berlin Philarmonie. He is also a Frankfurter and teaches at the design school in Offenbach. I also have the “Hare” by Dürer! (laughs)

I have an object that I made with my wife for the Architecture Biennial in Venice. In 2006, Armand Grüntuch and Almut Ernst designed the German Pavilion, and we, as one of the other firms selected, just had a small box in which to present our work. That wasn’t really adequate for us. We thought that the only option for the space we were given was to fill it with sound. We worked with the overlapping of sound and you, as a visitor, were engaged in the exhibit, the art awakened you a little to your life. This is polytonality. It is just so cool when different aspects of it come together! Actually, it is a lot more beautiful than a single, dull melody.

-

How has Bötzow district changed since you arrived?

It was only ten years ago that it began to change – and then it all happened quickly. Our house was the last one that was still unrenovated. Now the area is a bit bourgeois; everyone is like you or me and has two children. In 30 or 40 years, they will all be walking through the streets with walkers. (laughs)

-

Why is the architecture so conservative in such a cool city?

When I have to explain to a foreigner why German architecture, and especially Berlin’s architecture, is so conservative, I say: “Berlin had so many experiments in politics and architecture in the 20th century and they all failed! Since then, there’s been very little interest in experimenting. Berliners just look for something functional. But, actually, this is a fallacy. There are some stylistic qualities in Berlin. The fracturing of the city is certainly a theme. Whether or not that is really a quality? At any rate, it’s disappearing little by little.

-

True, a significant part of central East Berlin is disappearing and the area between the TV Tower and the Spree is being built up.

I’m on the side of the people who want to build on it – even though this goes against my professional interests! I don’t agree with huge, empty spaces in the middle of a city. It’s not even attractive. Ultimately, I would argue that densifying the city is a civic duty, because it is the easiest way to make the city sustainable. When you close gaps in a city, you have shorter distances to go and you can use the space that’s closed at the moment.

In fact, I would say that right now there’s too much empty space in Berlin, not too little. If we consider this empty space, we always have to think about the “Culture of Cultivation.” Care and cultivation are key within a garden or park; development is important to the value of these places, but the city can hardly afford it. It’s always sad when new plants begin to grow that don’t adhere to the space – or don’t look right from the start.

-

Do you have an example of bad landscape architecture in Berlin?

The park by Nordbahnhof is terrible, just hideous! It’s an attempt to design arte povera within a park. Then again, we also have parks that are just for our dogs and that can’t be! Parks should always be something special, they should be a city’s treasured possession. If a city can’t even provide this, then it is better off without any parks at all.

-

You designed a sports field on Niebuhrstraße in Charlottenburg. It invites those who use the space to negotiate their way through it. Do you consider the idea of occupancy to be a recurring theme in your work?

Definitely. I’m particularly interested in referencing this theme of free space because I like to consider the aesthetics of conflict. Free spaces are frequently places of conflict: people from different cultures and different social groups come together; they have different requirements when using the space; they are different ages, different genders, etc. We should consider how to use this conflict and friction productively, and how energy can be produced while still remaining interesting. Cities cultivate conflict. Therefore, gardens and parks are good places for this cultivation to be maintained.

-

Do you have a favorite public space in Berlin?

I think Tempelhof is really quite lovely – at the moment, without urban planning, it is the communal “place to be.” The space is created through people’s use of it. And it couldn’t be better. If a landscape architect set about working on it, without a doubt it would be worse off. But if someone strays from Neukölln onto the airstrip, from the small footways by the cemetery, that’s hard to beat. I think Tempelhof is like Versailles: it provides a similar feeling of space, one where the sky is suddenly incredibly apparent.

-

What makes TOPOTEK1 different from other landscape architecture firms?

We don’t have any stress or conflict. It’s a long-held opinion that gardening and landscape architecture are peaceful crafts. But the city is controlled and there’s hardly any space for those who come to “de-control” it. For me, I can spot conflict within this free space that is left. In the parks – especially if there aren’t very many – you encounter urban society. It’s public art, just like the publication of a book. Americans refer to “self-editing” – for me, parks are my form of “self-editing” where I can do my bit for the urban population.

-

Is that why you included a boxing ring into Superkilen Park in Copenhagen?

We asked ourselves, “How can we engage with the issue of conflict in a district which, at times, is really quite violent?” I wondered if I should try a style derived from Schinkel and design a classic park or impose this conflict upon the existing structure and quality of the place. Good cities are always places of cultivated conflict – Berlin as well.

“I think Tempelhof is like Versailles: it provides a similar feeling of space, one where the sky is suddenly incredibly apparent.”

-

What do you want out of your work?

I really love the work of BIG – the Copenhagen-based architecture firm TOPOTEK1 collaborated with on Superkilen Park. They provide a form of unmitigated positivity. Everything is fun, everything is nice, everything is easy-peasy. Naturally, this is all foreign to my work, where themes of violence, sorrow, discrimination and yearning are all hugely powerful and are provoked both within people and the city.

On the other hand, I am a child of 80s and am therefore probably also inclined towards post-modernism and Individualism. I believe that these are currently my two strongest tendencies. But stronger politicization, such as a return to humanism, which is both anti-religious and anti-national, as well as old leftist attitudes, also come out of my work.

I don’t have a universal solution. Instead, I make decisions intuitively – with careful pragmatism, but always with a desire to subvert. When an unexpected opportunity arises I often try to make use of these chances. Sometimes it allows me to play around. When that happens, it is certainly post-modern.

-

What are your thoughts on the other ways Berlin has developed?

The big question is whether Berlin has evolved into a classic metropolis. During the Imperial Era, Berlin was actually a boring city. Then, in the 1920s, the city gained a certain dynamism to its culture. Even then, Berlin could never stand in comparison to Paris, London or Rome.

Perhaps Berlin is so interesting at the moment because the 20th century is still so present here. In Berlin, like a doctor, you can still identify the open wounds – at some point this will surely disappear. It remains to be seen whether it will still be so sexy when the body is all stitched up.

-

You have projects around the world, but none in South America. Why?

People should know that landscape architecture is particularly present in Protestant countries. In South America we found that they still adhere to Romanticism, even if this tendency is weakening. If we think of a park today, we actually think of a romantic English garden with a couple of trees, a footpath, a pond. Perhaps a ruin or something as well… (smiles)

By contrast, in Mediterranean and Latin American countries, public space is used as a continuation of private space. People live outdoors; even the grandmas walk along the streets in the evening. What is more, Spain and Latin America have a different style for their parks. An insanely good example is the Paseo del Prado in Madrid. It’s a long promenade that is very green but paved as well. This style, halfway between park and square, creates a wonderful space because in the evenings people can walk to and fro, but also sit under the shade of the trees.

Find more information about TOPOTEK1’s landscape architecture projects here.

This portrait is produced together with USM for the series “Personalities by USM.” See a different angle to this story with a focus on Martin’s interior here.

Photography: Matthias Weingärtner

Interview: Achim Reese