From her studio in Tehran, formerly exiled Iranian artist Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian explains why she reconnected with her country and how cultures collide in her signature mirror works.

Tehran is a bright, whirling, magnificent wilderness. The air blows hot and heavy from the desert and brings with it the earth’s scorched residue; dust from another place where people are scarce and the moon hangs low, like a luminous stamp above stretches of sand and rocky outcrop. Through built-up streets this desert wind blows, past gridlocked cars from a forgotten era, against bodies swathed in cloth and faces shielded by headscarves. The people of Tehran carry on, remaining resolute against the dry heat.

This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who presents a special curation of our pictures on ZEIT Magazin Online.

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian lives on the other side of town. Tehran is more shining, shimmying colossus than common metropolis, and crossing the city’s dense sprawl takes resolve. After gender-divided subway systems are negotiated, heaving alleyways and human tidewaters, the foothills of the Alborz Mountains are reached. Monir’s house and studio live in close proximity to one another in the affluent neighborhood of Tajrish, which is located in the northern reaches of the city and flanked by a vast and snow-domed mountain range. Old trees line the avenues of Tajrish and create awnings of shade against the sun’s midday glare. The studio is unassuming—it lies within a walled enclosure off a side street and its white peeling paintwork looks tired, its gate a little rusty. A modest, light-patched courtyard gives way to the heavy doors of the studio itself and a blaze, far stronger than the Iranian sun, awaits inside. Monir’s studio dazzles and transfixes the visitor. Mirrored works hang from every surface and compete against one another in their quest to replicate and redefine. Fractured light glimmers from wall to floor to ceiling. In the centre stands Monir; her work surrounding her, engulfing her. She is 92-years-old and small, and her smile is wide.

The mirror works that Monir creates first took shape in the 1960s and ’70s when she returned to her native Iran after spending over 26 exiled years in New York after the Iranian Revolution. Her journey as an artist began long before the Shah’s overthrow; Monir’s artistic trajectory spans from her early days studying at the Fine Arts College of Tehran followed by graphic design work in New York and extensive traveling to Iran’s more remote regions. It was during this period that traditional Persian craftsmanship, Islamic pattern design, and western principles merged in the form of Monir’s distinctive art practice. After her return to Iran in 2004 and the establishment of her studio and design workshop, Monir resumed work with many of the craftsmen with whom she had initially collaborated in the 1970s. “When I came back from America, I lived in many different cities in Iran, and traveled all around Iran to find my country,” she says. “I was very young when I left… when I returned to Iran I wanted to see what my country was really like. What was this 3,000 year old culture? I went to many different cities as well as to the countryside to see what the history of our architecture and fine art was like. I traveled.” When asked what informs and inspires her, Monir replies: “Everything. Traveling, being born here in Iran, seeing mirror works in Shiraz, the mosques, the palaces—everything.”

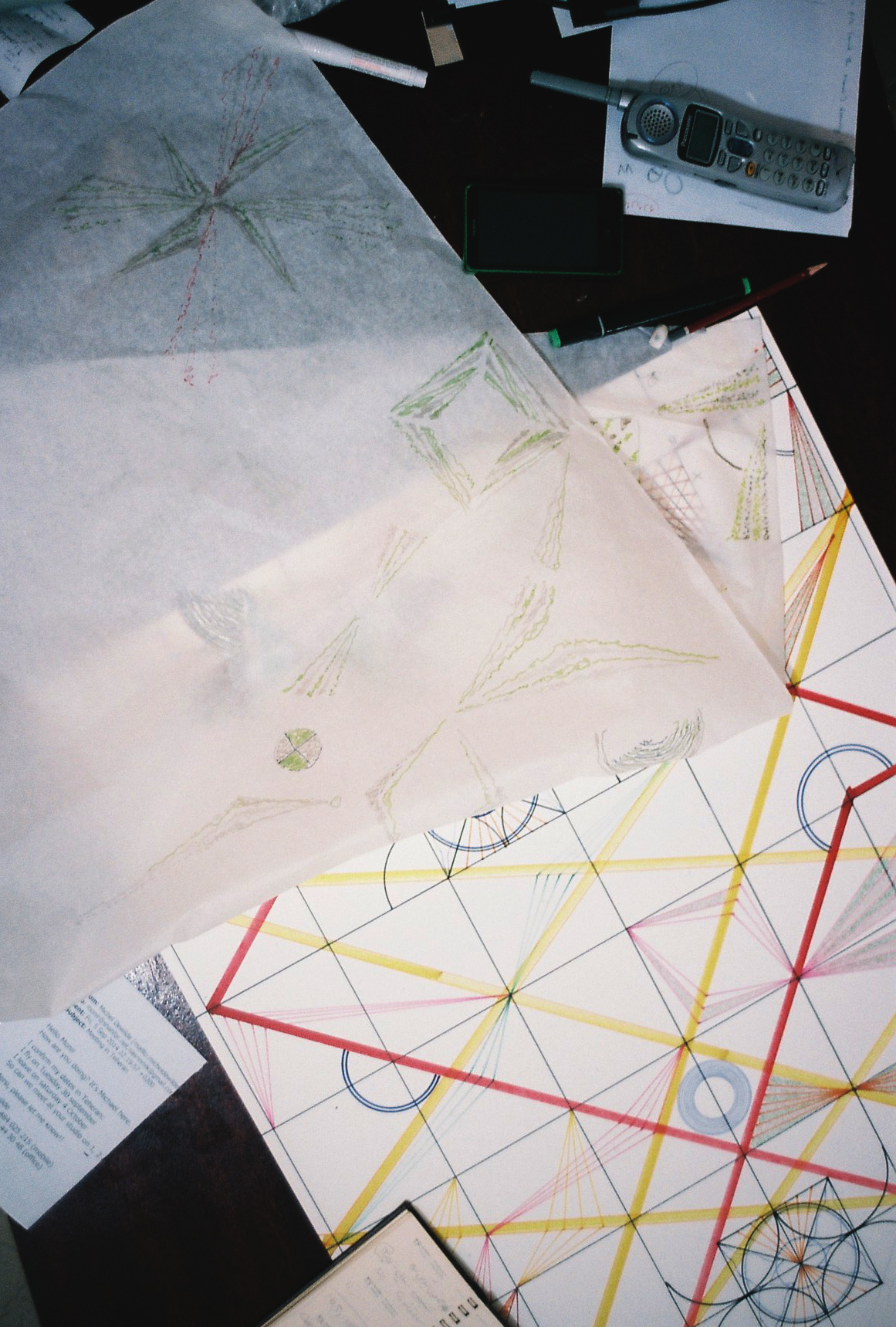

The age-old Persian artistic temperament lies at the very heart of Iranian culture, despite tensions between pre and post-Revolutionary Iran. Monir’s work draws from both these worlds; she delves headlong into Persian mysticism while simultaneously invoking the current social and political landscape of Islam. Her mirror works reflect this collision. Monir refers to her mirrored pieces as ‘geometric families’, the essence of which is easily recognizable in the geometry of Iran’s heritage. The mosques, shrines and palaces that extend throughout the nation are laced with mirror work and geometrically exacting decorative features.

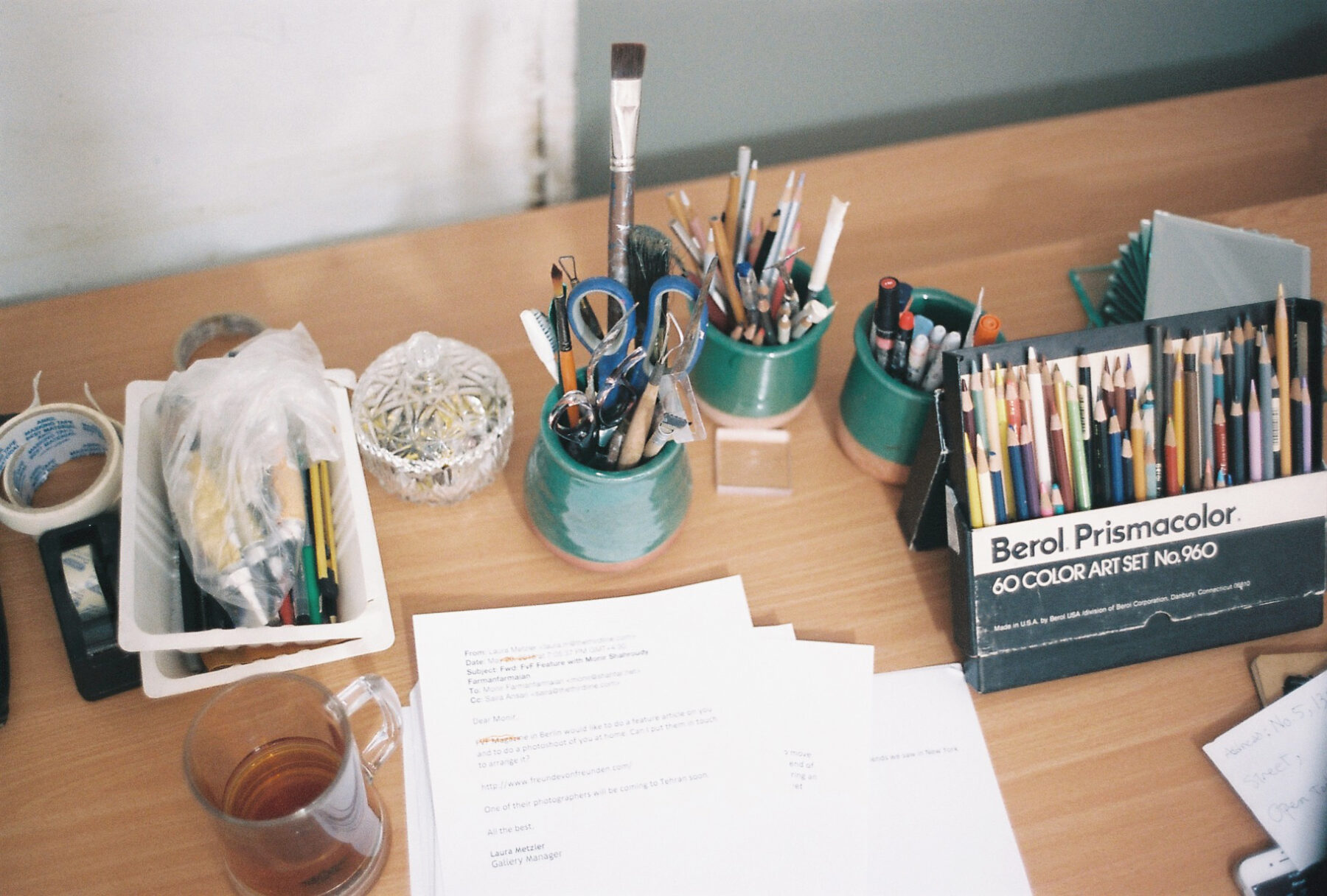

The mirror sculptures that are housed within Monir’s studio are a mixture of old and new work. Having recently returned from a trip to New York for the opening of her first comprehensive exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum, Monir wastes no time in reinstating her studio practice. Her workshop, which adjoins the studio, emits a gentle hum as glass is scored and cut by local craftsmen, using the techniques of Islamic design principles. “My work is based on geometry, and geometry starts from the triangle, square, pentagon, hexagon, octagon and all that. And you can design many different forms in many different materials from these geometric foundations and principles.”

Monir, thank you for letting us into your captivating world and studio. Find out more about Monir’s internationally renowned work on The Third Line gallery’s website.

Want to see more artists’ studios and creative spaces? Head over to our workplaces section.

Photography: James Whineray

Text: Lucy Byrnes