Nature, awareness, deceleration, meditation: shinrin-yoku, meaning ”‘bathing in the forest,” is a recognized treatment in Japan. It’s also spreading to Germany as a by-product of the general mindfulness trend.

In Upper Bavaria’s Mangfall Valley, the forest is still surprisingly lush. There has hardly been any deforestation in the water basin around Munich, and the woodlands are left largely to their own devices. Leading a tour through this untouched landscape, Emma Wisser and her partner Carlos Ponte reflect on the meaning of shinrin-yoku, the Japanese method of experiencing the woods with all your senses. “In a figurative sense, it means absorbing the forest, enjoying it, placing oneself in a direct relationship with nature, the trees, wind, light, and soil,” Wisser elaborates.

Bathing in the forest is an officially recognized form of therapy in Japan and the United States. Is it just a walk? Is it going to be strenuous? “Bathing in the forest is not athletic at all. But neither is it a walk. It’s actually more of a sojourn. We are in the forest, with the forest, and can allow ourselves to be surprised by what happens. How we feel, what we sense—the responses are always very personal.” Shinrin-yoku was introduced by Japan’s Ministry of Agriculture in the early 1980s. It started out as a marketing campaign: The idea was to encourage people to appreciate the forest, to recognize its beneficial effects, and to stop perceiving it merely as an economic resource. The ministry poured millions into researching the forest and its salubrious effects. Soon afterwards, the first center for forest therapy opened its doors; these days, medical students at Japanese universities can even qualify as specialists in forest medicine. In Germany, forests cover almost a third of the land, making it one of the most wood-laden countries in the European Union. Medicinal forests are emerging, especially in the rich woodlands of Mecklenburg-West Pomerania. Across both countries, it is said that the forest can alleviate physical symptoms and provide relief from emotional afflictions.

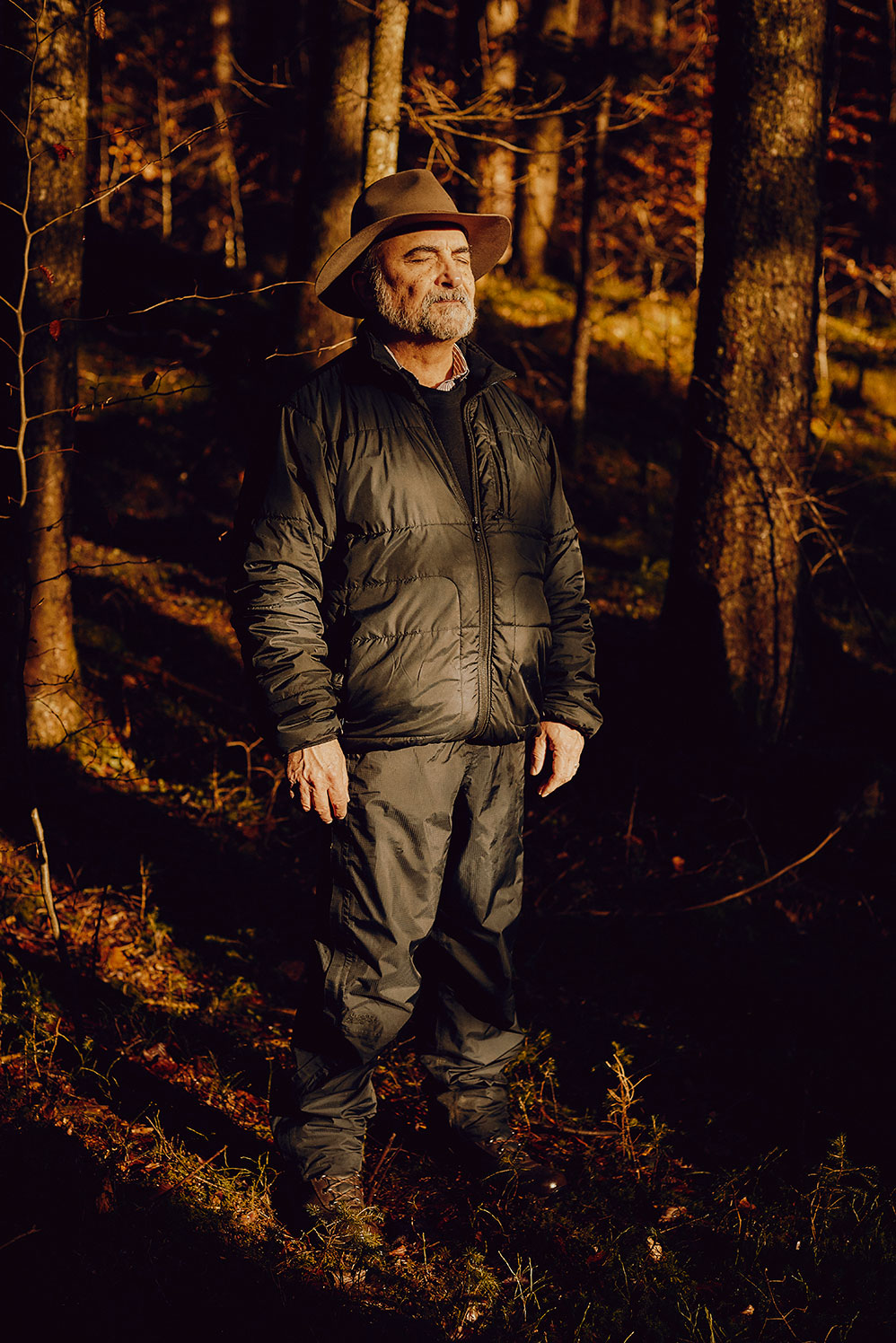

Ponte and Wisser have been organizing these tours for two years now, twice a week in summer and by appointment in winter. What brought them together was meditation, or more precisely, an app. Originally from Argentina, Ponte had worked as an IT forensics specialist in Canada, seven days a week, for decades. “I had no life left,” says Ponte—so he took up meditation. He discovered a meditation app that allowed him to communicate with like-minded people. And he kept coming across a photo of Wisser, who runs a practice for mindfulness and self-compassion in Munich. Ponte and Wisser started messaging, and then talking on the phone, eventually arranging a date to cook together. When they discovered that they share the same birthday, Wisser dropped everything, sold his house in Calgary, and moved to Weyarn in Bavaria. “We decided to work together on mindfulness, with a holiday component. European vacations with a mindfulness twist. Here we have space, peace, and nature around us,” explains Ponte.

“Shinrin-yoku means absorbing the forest, placing oneself in a direct relationship with nature, the trees, wind, light, and soil.”

Scientists around the world are investigating the psychological and physiological effects of shinrin-yoku. Their work began in the ’80s, when biologist Edward O. Wilson proposed the biophilia hypothesis, which describes the innate love that humans feel for all forms of life around them. It is part of our DNA—the result of an evolutionary process spanning millions of years. Swedish scientist Roger Ulrich discovered that hospital patients recover faster if there are trees outside their windows. And Qing Li, a Japanese researcher who has penned dozens of studies on the medicinal effects of the forest, determined that our blood pressure, cortisol levels (stress hormone), and heartbeat drop noticeably after only an hour in the woods.

The Japanese believe that forest air extends life. It’s true: Strolls through woodlands strengthen our cardiovascular systems and boost our natural defenses. Scientists at the Nippon Medical School have found that white blood cell activity can rise by as much as 50 percent after a few hours spent in the forest. Not only do these cells fight germs but they also help to prevent cancer. Qing Li believes that terpenes—messenger substances in trees—are responsible for this effect. Trees use these volatile organic compounds, known as phytoncides, to fight off pests and diseases. Scientists in Germany are now also investigating whether forests, with their significantly different set of trees compared to Japan—oak and beech trees, instead of cedar and larch—could have similar effects.

“Mindfulness enhances the effects of the forest. It’s humbling to see that we’re making a difference in people’s lives, one at a time.”

When it comes to the walks themselves there are no rules. It’s about experiencing the forest like children, tracing hands across the bark and the lush verdant moss, breathing the clean air, and gazing up as the treetops sway in the wind. According to the pair, to experience the woods, we need to open our spirits, dispel nagging doubts, and welcome nature in. “We are trying to find a balance between an academic and an esoteric approach,” says Ponte. “Mindfulness enhances the effects of the forest. It’s humbling to see that we’re making a difference in people’s lives, one at a time. It is rewarding, and a big responsibility.” Ponte recently returned from Japan, where he shared ideas about shinrin-yoku with the prestigious researcher Yoshifumi Miyazaki, and took time to visit the Akasawa National Recreational Forest, to which around five million Japanese flock every year. Forests play a significant role in Japanese history and mythology.

Not only is this nature-based mindfulness a blessing for the spirit—it’s also one for personal growth. Towards the end of each walk, Ponte gives walkers a handout with tips on how to incorporate shinrin-yoku into everyday life—in the green lungs of the city—to take a little break from the rationalism, hedonism, and materialism of urban existence. “For 99.9 percent of history, human beings lived in nature,” says Wisser. And even though around 1,300 square meters of forest would theoretically be available to each person in Germany, hardly any of us make use of it. “We are all part of nature, even if we don’t feel that way,” adds Ponte as he leaves the woods behind. “This is not only a forest. This is home.”

To book a Shinrin-Yoku day retreat or find out more about Carlos Ponte and Emma Wisser’s activities, you can visit their website Mindfulness Vacations & Retreats. This story was originally published in Companion #15, a magazine produced in collaboration with 25Hours hotels. Find more Companion stories here.

Text: Florian Siebeck

Photography: Conny Mirbach