In Japan, one’s lifetime is measured in 60-year cycles. When you reach the age of 60, you celebrate birth once more, returning to the world as a newborn baby. Mikio Hasui says this year, when he turns 60, he will hit the reset button on life.

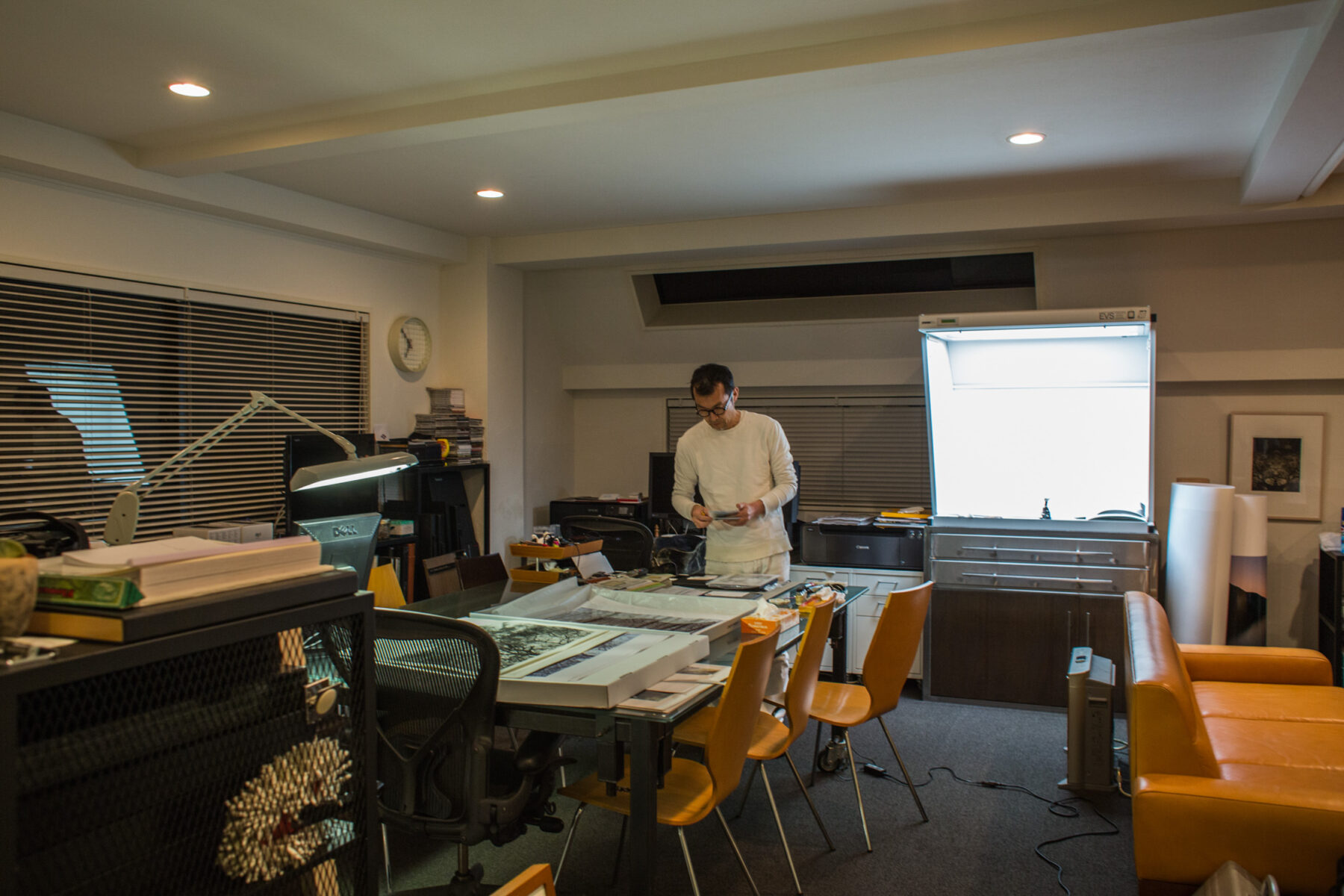

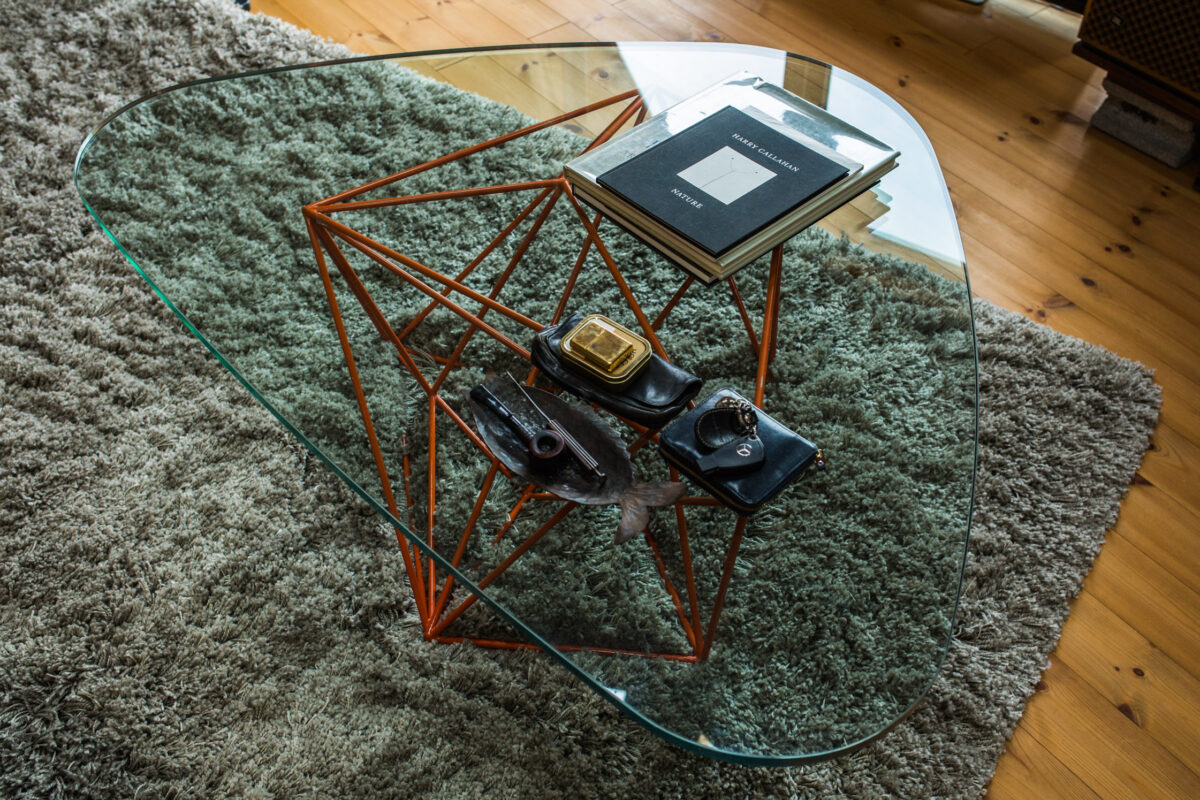

Hasui makes the perfect cup of coffee, from Tanzanian beans roasted in his kitchen. A selection of mellow jazz tunes play in the background on two large Altec Lansing speakers from the 1960s. It is the first few days of the rainy season in Tokyo, and the colors in his studio are muted and hazy. One of the first things he says is how much he misses the kissaten culture, where one sits for hours over coffee and cigarettes in traditional tearooms. Surrounded by his work and favorite objects, it seems that he has recreated his own kissaten here.

It is an ideal time and place for reflection – on his commercial and personal works; his two marriages and three kids; his identity; his views and responsibilities; his place in the world. What comes next, when he turns 60? For starters, he’s planning a big move across the world to New York, where he says he will eat crab sandwiches until the day he can properly order himself a club sandwich for lunch.

This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who presents a special curation of our pictures on ZEIT Magazin Online.

-

How do you introduce yourself to those who don’t know you?

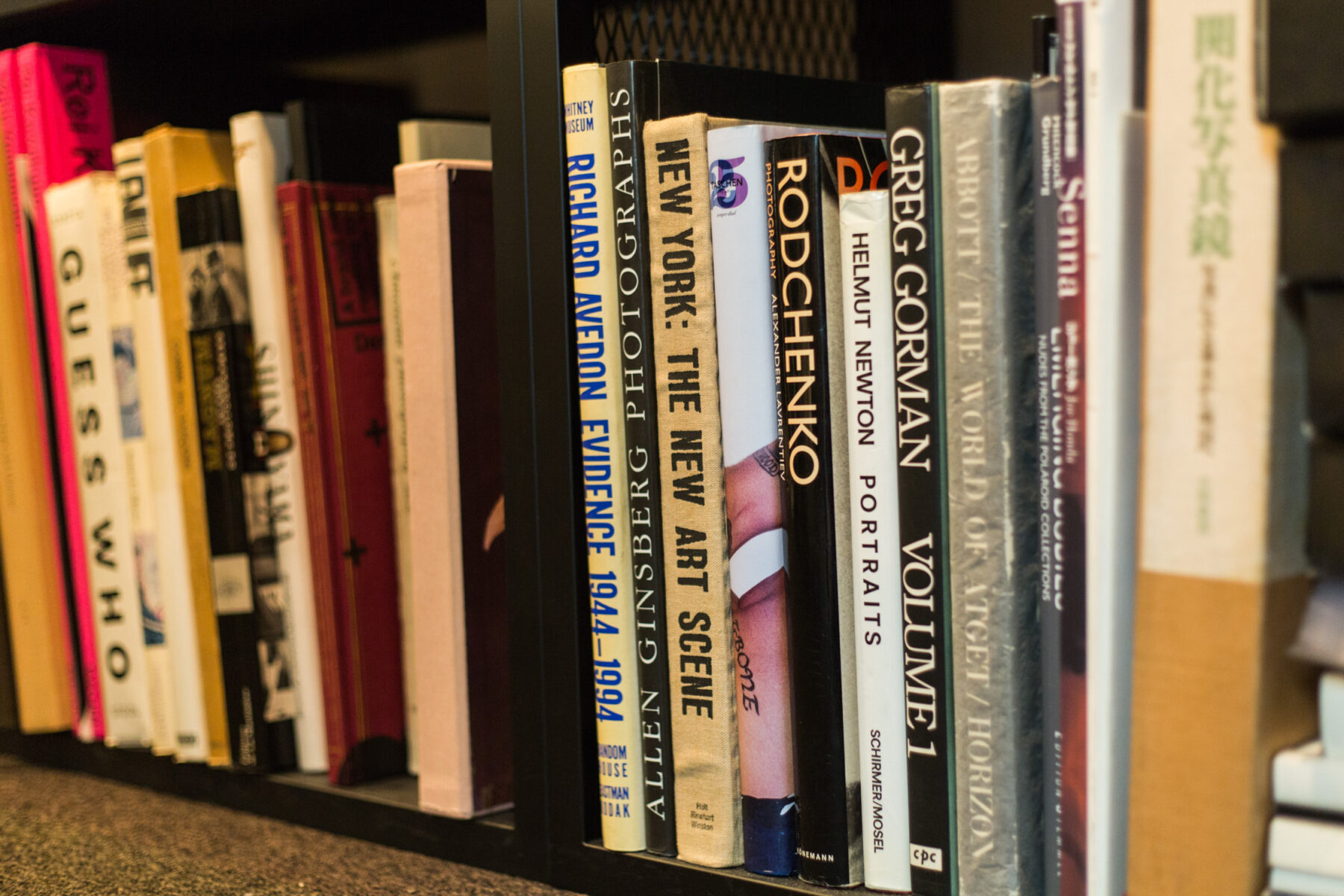

I’m a photographer first. The core of what I do is photography, so I call myself a photographer. It’s the most straightforward way to describe myself. I’m not an academic photographer, though – I never studied art. I’ve never worked for another photographer so I’ve never been an assistant. It’s all been self-taught, self-learned. But because I don’t have an art school or photography background, I’m not bound to the title. Photography is a language I use to communicate. I’m also a director, artist and designer.

-

When you were a kid, what did you want to be when you grew up?

Nothing. I didn’t want to become anything. I just wanted to play. I hated school work. When I was in elementary school, my mom celebrated by making sekihan – rice with red beans – when I came home with a C, because I usually just got D’s and E’s. The final year of middle school, I got called to the teacher’s office and was told that I should find a job straight out of middle school and not even try to get into high school. I think my parents hoped that I would at least finish high school so I took the entrance exams, but I failed all of them. No one would accept me as a student. In the end, there was one school, Meiji Gakuin, the most hopeless high school of my time, that was accepting second-call applicants who had not gotten into any other schools. I managed to somehow squeeze in there.

-

Have you always lived in Tokyo?

Yes, mostly in Tokyo. I grew up a bit in Osaka, from when I was four until my last year of middle school. Since then, I’ve always been in Tokyo.

-

When did you move to your current studio?

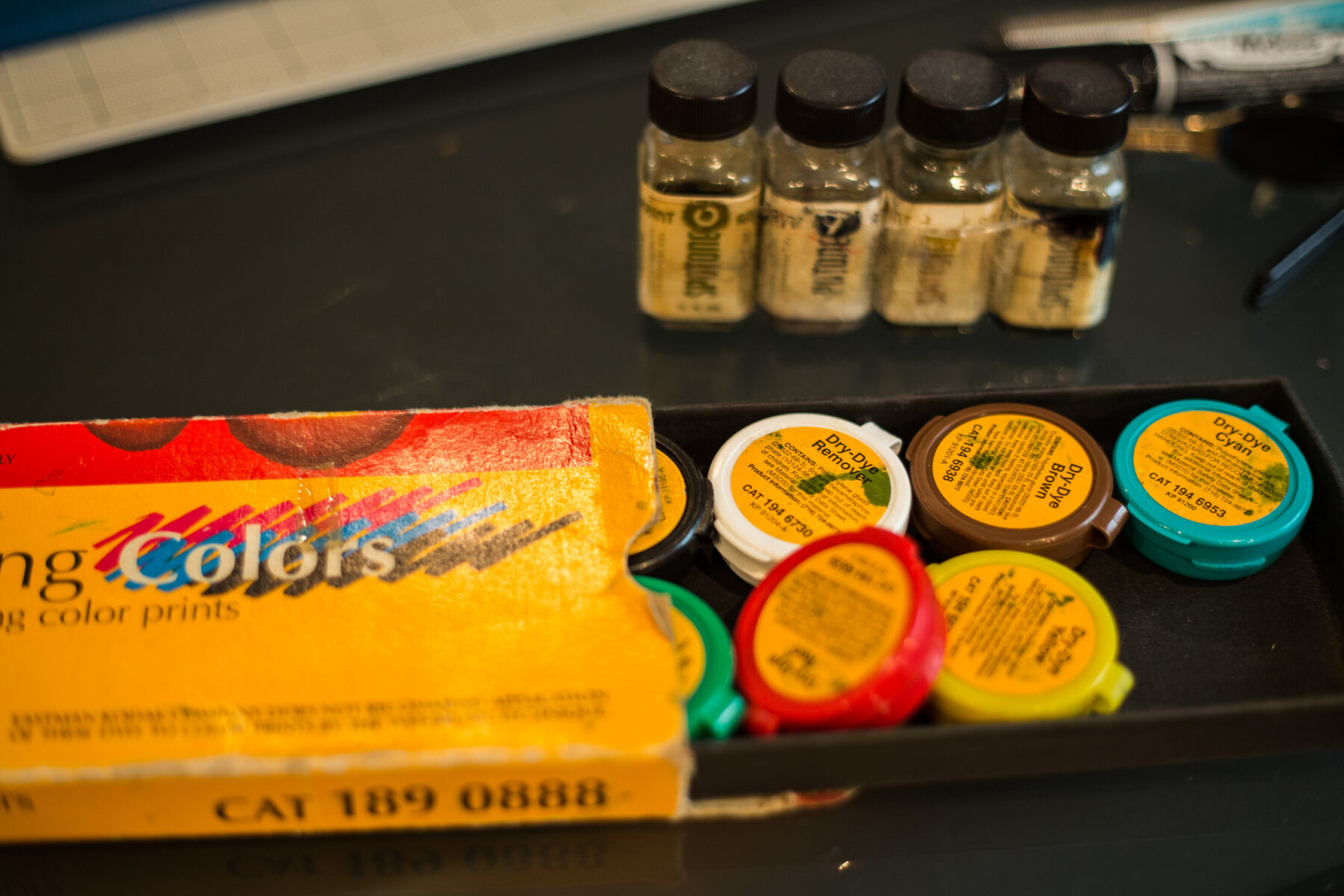

I built the studio here in Gohongi in 2000. I brought my mom to live on the second floor and made the first floor my atelier and studio. I have my darkroom set-up here, as well as my office. I also built a house in Fujisawa, where I lived with my wife and youngest daughter. When we got divorced and they left that home, I sold the house.

-

And when did you move into your current home?

As I was wondering where I should live, I went to Chino in Nagano for a job, and thought, this is it. I want to build a house here and live here. I was already looking into dome homes built by a company called Bess. Dome homes are strong and can withstand storms and natural disasters, and the space inside is such a unique shape and works well for sound.

-

You own some serious audio systems – are you an audiophile?

I wanted to be a jazz musician at one point. I was practicing to be a saxophone player and would frequent jazz kissaten during that time. This was more than 40 years ago, but the cafes would have these huge audio systems and they would play music really, really loudly. It was always my dream to own my own audio set-up, and in my 50s – when I was finally able to build my own home – that audio dream came true.

-

You keep a blog, as well. Do you enjoy expressing yourself using the written word?

Words, they’re difficult. I’m not a good writer. When I write, I feel like my thoughts get whittled down, smaller and smaller. With a photograph that I think is beautiful, eight out of ten people will also think it’s beautiful. The other two people may think it’s sad, and that’s okay by me. With words, beautiful is beautiful. You don’t read the word ‘beautiful’ as ‘sad’. The reaction people have to my photos can be unexpected, and I like that.

-

When you work on commercial photography as opposed to your personal work, what’s something you refuse to compromise on?

I ask myself if I am being true to myself. I won’t take the job if I can’t be real with myself in order to get it done. Some people can separate their commercial work from their personal art. I can’t. They’re both me. With commercial work, if you do it right, you can get a little bit of love in there. You can be thoughtful. There’s not that much difference in the things that are born from me. That’s why I still do commercial work.

-

That can be really difficult. Do you think you’re good at navigating that process?

I don’t like it when there’s no reaction. I like feedback. An artist can put things out into the world and commit to just that. But with commercial work, when you put something out into the world, you get something back. There was someone I used to work with who would give feedback like, “Can you please make it brighter? Hasui-san, this won’t work as is.” Before, I used to retaliate and say stuff like, “you don’t know what you’re talking about.” But not now. Now, I appreciate that perspective. I’ve learned to say, “If we just make it brighter, we’ll lose these elements, so let’s revise it like this instead.” Through that process, I’ve learned to be curious about people, and to understand people. In my mind, I’m thinking, that guy is actually pretty dark and brooding, that’s why he prefers bright, cheery images. I’ve learned to enjoy those kinds of interactions with people.

-

When you shoot, do you prefer people as subjects, or nature?

I like both. The reason I shoot nature is, when you go into the woods it’s refreshing to everyone. Everyone’s hearts melt a little bit when they look at the sunset. It’s just nature, but why are we all moved by it in the same way? I think it’s because it’s in our DNA. It’s programmed in our DNA to love nature and to protect nature. I used to rebel against that and never photograph sunsets, because every shot turns out like a postcard photo. Now, I just follow my human heart and instincts and take the photos, remaining conscious of framing, angles, the color or tone. I take that sunset photo but try and make it new, seeing it with fresh eyes. I think there’s creative opportunity in that.

-

Did falling in love, getting married and raising kids influence your work?

Everything that has happened has influenced my work – my children, my past marriages, all of that. My work was made while I was with all of these people, so that’s come out in my expressions. I think it would be kind of sad if it didn’t.

-

Have any of your children pursued the arts?

My son, Motohiko Hasui, is a fashion photographer. He’s doing really well in Japan. When he was in his final years of high school, he told me, “Dad, I want to become a photographer.” I asked him how he would do it, and he said he wanted to pursue a photography program at a Japanese university. I told him, “No, go study overseas.” So he entered Central Saint Martins in London, then London University for their photography program. He’s been back in Tokyo now for about eight years, and he’s married to Akane Utsunomiya, who is a very talented knitwear designer.

-

Was it your wish that your children spend time overseas and learn to speak English?

Definitely. That was very important. I feel that my lack of English has limited my world considerably. I decided that my son and daughter were to be educated abroad. Their mother was a bit hesitant, but I pushed them to go and I don’t regret it. I think that both of them have grown up to be adults who aren’t limited to Japan. Japan is a wonderful country, and there’s much to be proud of, but it’s also a small country. I think that in this generation, you need to be a global citizen. The more time you spend outside of Japan, the more you appreciate the Japanese-ness inside of you. Isn’t that a great thing? I think there are Japanese people living in Japan who have never fully realized how great it is to be Japanese.

-

What’s next for you?

I’d like to take my next project to New York. I’m applying for an artist visa right now, and ideally, I would like to go back and forth between Tokyo and New York. If I go to New York, I’ll be forced to use English. I’ve done all sorts of things to pick up the language here, but if I’m actually there, I’ll probably use it more.

I’m turning 60 this year, and when I do, I’m thinking of hitting the reset button on my life. Not to say I’ll stop being an artist or a photographer. It’s hard to put into words, but it’s almost like turning something monochrome into color. I’m feeling like I can get to the next step. I’d like to get away from the classic style of photography and move toward the abstract.

-

You’ll probably get much more variety in terms of reactions and feedback through abstract work.

Until now, I had this policy to stay away from violence, sex and discrimination. When those themes become abstract, expressing violence can be anti-violence, and sex can be expressed as a beautiful and positive thing, not just as eroticism or perversion. I despise any sort of racism or hate, but if you change the way you express it, it could counter that message. The strict rules and barriers that I had in me before, have started to change.

-

Did something influence you to remove those rules and barriers?

It’s been a natural path, with age. Perhaps at this point, because you’ve gone through so much life already, you start to realize that you’re going to die someday. It’s huge to really face the reality of impending death.

-

Is this a recent thing for you?

It’s been the last few years. A few of my friends have passed away, but I’m still alive. When you turn on the TV, you see air strikes killing thousands of people on the news, and innocent kids getting caught up in war. We all have this thing called life, but because of geography, of time and place and situation – why do their lives have to be so different than mine? I think about that, and it shocks me and saddens me. I’m born Japanese, and raised in Japan, and now I have this safe place where I live and that I identify with. With that comes two things: one, is that I appreciate it. I want to live in this environment and not take it for granted. The second is, how do I take this gift of life and wealth, and how do I share it with those who are not as privileged? I want to be aware. I never want to be complacent.

-

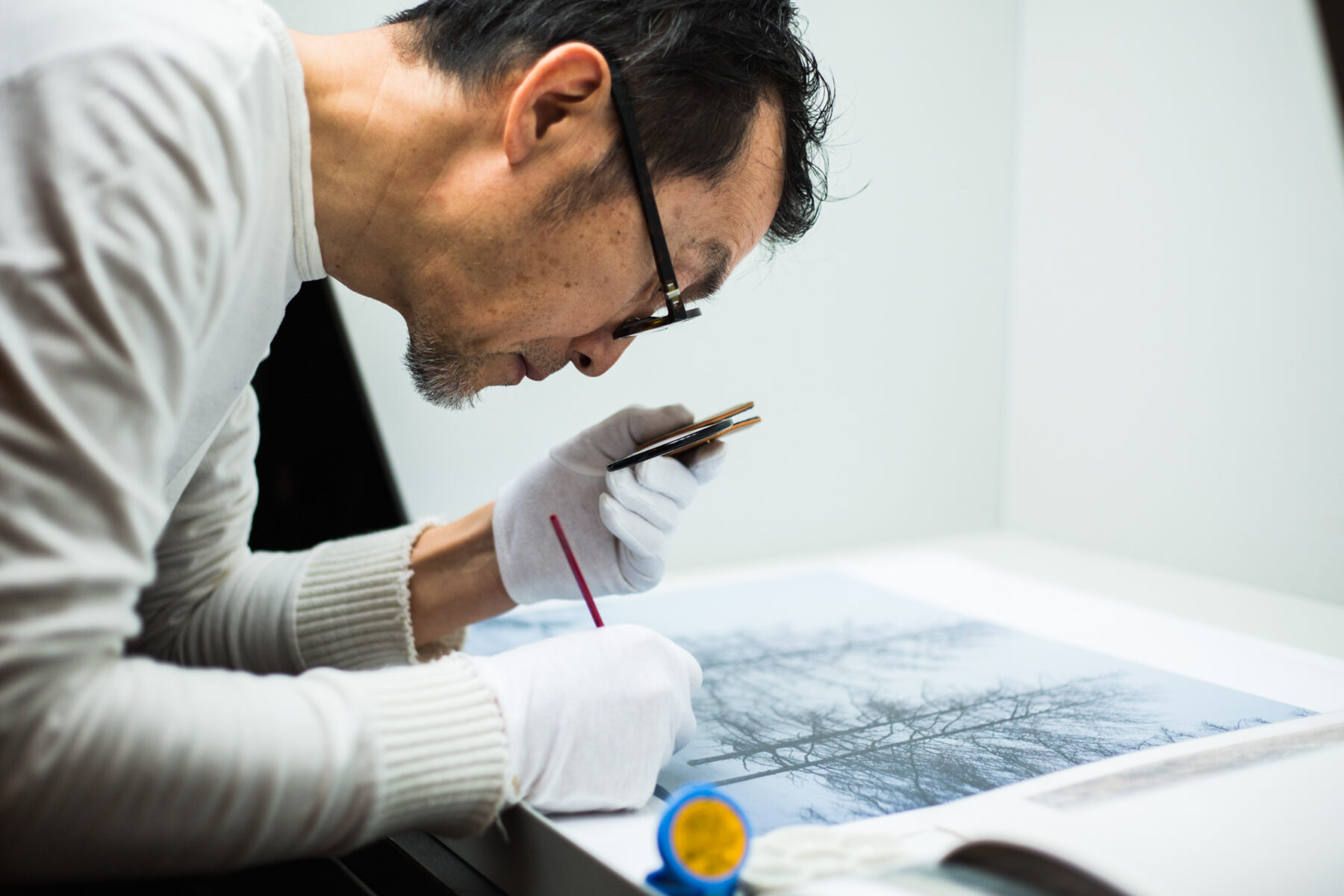

What are you working on right now?

My new photo series is on fogs. They are all white – just fog, with a bit of landscape. So when you go to the gallery, you walk into a room with white photos on the walls. When I went to shoot these images, it just happened to be foggy. I was thinking, I can’t shoot today. I couldn’t see anything, so I waited a bit for the fog to clear. When the fog lifted for one moment, I saw the mountain, covered with trees in bright autumnal colors. But I was thinking that if the fog wasn’t there, and it was just a mountain covered in autumnal leaves, the experience and shot would’ve been pretty boring. It was beautiful because it was hidden, and because it was only revealed for that one moment, just that one part of the mountain.

I felt like it was a metaphor for my life. I’m living in a fog. Even though I’m facing forward, I’m not sure which direction that is. I don’t belong to or work at a company, and I live life day by day. Sometimes I’m like, is this all right? Is this okay? But that’s the kind of thing everyone thinks about. I wonder what’s ahead. Work, marriage, kids – everyone has those questions. But when you’re inside the fog, when everything is foggy, you can’t see (what’s ahead of you). When that fog lifts and you can see even a bit of something, you’ve got to believe in what you just saw, right? When the fog lifts, there’s that mountain covered in trees with beautiful leaves and colors – you can’t see it right now, but it’s there. You’ve got to believe in that.

Hasui-san, thank you for sharing your home and studio with us. Learn more about Mikio Hasui’s photographic work on his website. Read more interviews with intriguing personalities based in Tokyo.

This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who presents a special curation of our pictures on ZEIT Magazin Online.

Photography: Shinji Minegishi

Interview: Akiko Kurematsu