Born in Hammersmith, London in 1963, Lawrence Watson left school at 16 to apprentice in a darkroom on Old Street. He then graduated to work at London Weekend Television, and while there developed his portfolio in the evenings and weekends. Lawrence discovered his passion for photography in London, playing in the basement darkroom of a friend’s father. Still in his teen years, Watson rose to prominence as a photographer for London’s New Musical Express, where he gained attention for his striking images of musicians and concerts.

In the early 80s, Watson was commissioned to document the emerging New York hip-hop scene, where he explored the new genre of music developing in America. Since that time, he has photographed musicians like Paul Weller, Morrissey, Snoop Dogg and Grace Jones, to name a few. Though Watson is extraordinarily humble, he is one of the most talented photographers in the music business. Here, he talks to us about his last book in collaboration with Adidas, darkrooms, and how to catch the moments in-between. Find more information about his exhibition with Noel Gallagher below the interview.

What was the first camera you ever used?

I think it was a little old Yashica. I can’t really remember the code of it, but it was second hand.

Do you remember what age?

About 15. Yeah, a friend’s Dad had a little darkroom in his basement and I found it pretty fun to work in there. When I was about 16 I had the choice of going back to school and doing A levels, but my Dad told me I should get a job. He asked me what I liked doing, and the only thing I had done at that point was a bit of photography.

And you were able to make some money from it?

Not very much in the beginning. I worked in a darkroom down on Old St in the beginning. But then my brother started writing for the New Musical Express, so I started going to the concerts and gigs and taking pictures there and after a time NME started publishing the pictures and I got into music photography.

So, was there a point in time where you decided to make a living out of photography?

No, it just so happened that I fell into it and it was something I enjoy doing. And I suppose it’s always the best if you can make money out of something you enjoy doing. That’s always the best.

And so, how did the transfer go? Did you start with music photography?

The pictures I took for myself were initially all reportage-y sort of things. I had all the right wing movements and right wing parties and demonstrations.

But it was all kind of action-oriented documentary? People moving around and sound?

Yeah.

Did you always have an interest in music?

I tried to play bass guitar but wasn’t that good at it. I used to be a bass player in an old punk band called UK Subs, and they used to play in a club called Club Garden. They had a darkroom in there as well where I could do some printing. but I think they gave up on me after about six weeks of trying to play “Walk on the Wild Side.”

So, have you always shot analog?

Yeah, I started with it and I still try to do a lot of my work on film, but I can finally confess that I have a digital camera now. But it’s fine, it’s a tool and I’m starting to make it do what I want it to do.

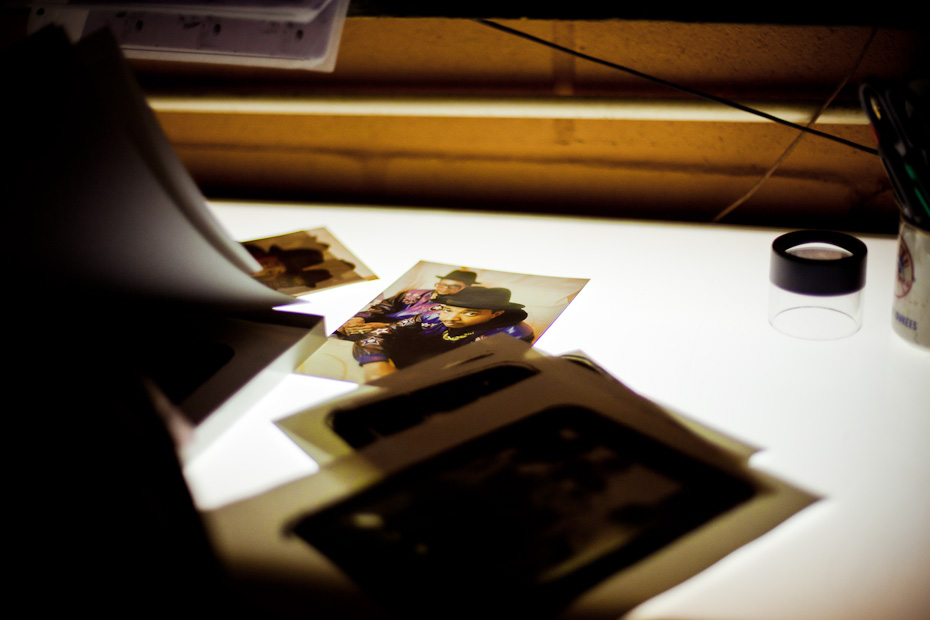

Do you like the production process behind analog photography?

I find it a really lovely, wondrous thing…You don’t know until you actually process the film, then contact it. It’s great to look at the contact sheet and think, oh I’ve got it.

Is that the best part of the process?

That’s the fun bit, definitely. Because, as you see in the darkroom, I mean I’ve taken my sons down there and stuff and they can’t get their heads around it, you know, that this horrible little smelly room is where I get my kicks. You know, it has all the fungus on the walls and the horrible, smelly chemicals. But this is really where it comes together, where I know I’ve got the shot I’m happy with.

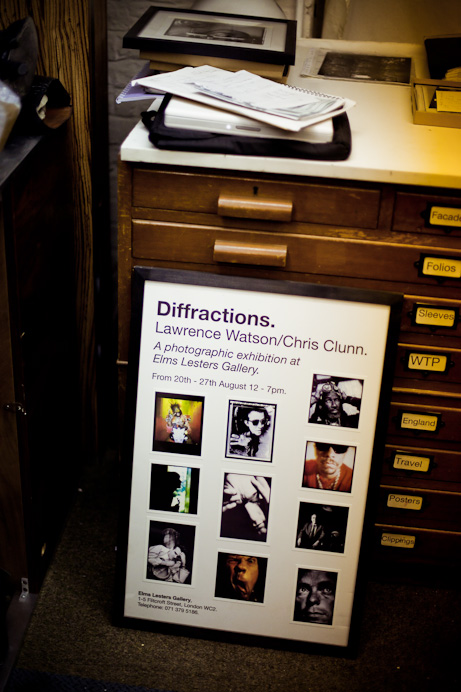

Tell us a little bit about how the book The World is Yours evolved.

The book came initially from an exhibition on Redchurch Street in East London, at Maverik Showroom with Angelo Carnielo. In the back of my mind I knew I’d always wanted to do a book, and then a friend Gary over at Adidas asked what I wanted to do with it, and I told him I’d love to do a book. He noticed that a lot of the musicians were clad head to toe in Adidas gear and told me to go talk to them when I was ready.

So did Adidas handle the art direction?

Well, I used my art directors, a company called Fruit Machine, but it was an ongoing collaboration between Adidas and my guys.

Did you get the selection that you wanted or was it a push for more Adidas?

It was a bit of “one for me, one for you” kind of thing going on… but it was fine, they helped out a lot with the book, so it was something worth doing because I wouldn’t have been able to afford putting that book out myself. Collaborations with brands are always great when you have a brand that supports the artist and doesn’t do too much to it. Adidas wasn’t doing it as a chief advertising campaign. It’s still somebody’s document, you know.

Did you shoot the Beatles, ever?

McCartney’s in the book. I think it was the first time he’d been back to London in 18 years, so I was very lucky to get a picture of him, and low and behold he’s wearing Adidas!

So, who was the most fun to photograph?

I enjoy the company of musicians, because I think most of the good ones enjoy what they do. I think the ones who really enjoy their music aren’t too bad about having their photograph taken. They’ve gotta do these pictures, but I try and make it as painless of an experience as possible.

When you photograph musicians, do you have them just carry on as they would have, or do you stage them?

I try and let things happen organically and naturally.

Catch the moments in-between, like photographers always say?

Yeah, I think these kind of pictures always stand the test of time. That’s not to say that when I’m out on location I can’t do a bit of direction, but once I’ve got subjects roughly where I want them, I normally leave them to their own devices. I’m not really a hands-on kind of photographer.

Any crazy stories from projects?

I’ve gotta protect the innocent. But there are lots of funny things that have happened/ It was always great doing the hip-hop projects in America because people would wonder, “Why did these two white dudes just come all the way to America to do these interviews when the papers in England and our own country aren’t even writing about us?”

How did you find out about new musicians?

When we went on trips, I’d always check out the local record shops and look for old classic or vintage stuff, like old James Brown. So I’d end up going to all these black record stores and hear what would be playing. I once went to a little record store in Philadelphia and came back with a Schooly D album that I passed on to somebody and then suddenly Schooly D was signed.

So you had a natural curiosity about music too?

Yeah, and a lot of it was the journalists that I traveled with, too. They did a lot of tracking. But I’d be given a long list of records to hunt down as well because my stepbrother was DJing a lot. That was always the pastime when we were in America, to track down all these vintage things.

How do you build a connection with the people you photograph?

I don’t know if there are any secrets, really. A lot of it has to do with not using pictures without proper consent – Having respect for what the musicians do. Also, how you go into a photo shoot is important as well. I’ve never been a fan of those photographers that go in with a big ego because it changes the whole dimension of the shoot. I’ve always been happy to be the fly on the wall and I think lots of musicians prefer that.

You keep their pictures locked away and don’t sell them, right?

Yes, not unless it’s something they want to use. Or, if someone approaches me I can ask the musician’s permission to use it. I mean I got permission to use all of the photographs in my book. But I was lucky enough to get permission for the exhibition and the book because I waited 25 years to show the pictures, so people knew I wasn’t out there abusing the trust.

How was your relationship with Paul Weller, are you still working closely together?

It’s good. Yeah, he’s very much of that era. He’s very important, but what always used to happen with him is that he goes in and out of fashion. But his last album got rave reviews and suddenly everybody’s trying to pat him on the back. He’s nominated again for the Mercury Prize.

When did you meet him?

I used to go and see The Jam when I was 13 and 14, but I didn’t meet Paul until later. The Jam was very important to me when I was growing up. I loved all the punk and reggae bands. Luckily the keyboard player’s then-girlfriend worked at the press office of a TV company that I worked at on the weekends, in their darkroom, and she knew I was a big Jam fan. Paul was really good at encouraging people to come along and take pictures, so I went along once and took some photos and spent the whole weekend printing them. I was very lucky that he liked the pictures and decided to change the artwork on his album.

When you were younger did you have any role models in terms of photography?

All the NME photographers were really good. Anton Corbijn, Penny Smith, Kevin Cummings. At that time the NME was really the place to get your photos printed because they respected them, didn’t put text over them and really let the pictures breathe. I loved all the Magnum photographers: Cartier-Bresson and Eugene Smith. And Robert Frank’s pictures of the Stones.

Because we just talked about the lighting at the venues, are there certain things you always have to look for when you shoot at concerts?

It’s really important to look at where the lights are and how people are performing. You have to be able to wander around. That’s the great thing about having the access, you know, wandering around on stage and finding places where you can get a good picture.

You’ve been documenting the music industry for so long now. How do you think it’s changing at the moment?

Yeah, well there’s not very much money in the music industry anymore, but luckily I’m in it because I love music. So hopefully these changes have weeded out the people that are just trying to make a buck off of it.

Your website is still in the process of rebuilding, right?

Yeah, I’ve got a digital camera at least. I’m not big on the computer side of things, but I’ll get it sorted out eventually.

Do you have all your pictures digitized?

Some of them, the images that I used for the book were all scanned in, and some of the exhibition stuff too. But a lot of it still exists only in negatives. I think that’s probably a five year job for somebody, to sit down and go through it all.

How was it to work with Grace Jones?

Brilliant. That was a memorable session. It happened over a few different days because she ended up having to go back and rehearse with her band for a last minute concert, but she was good to her word and she came back to finish the session. She’s really creative – brings all the clothes and bits and pieces.

Did you have subjects that were more difficult in front of the camera?

Sometimes. But if you’re patient and if you’ve got time, then pictures happen. I compare it to going fishing. You’ve just gotta wait a while sometimes.

Are there any artists that you always wanted to capture but never had the chance to?

I loved all the old music with lots of character, like Johnny Cash – that whole period where rock and roll really took off and was fresh and brand new. Those times, the beginning of things, that’s what’s really magical. Now as I get older it’s probably hard for me to get involved with younger bands. It should be youngsters who are taking those pictures, anyway. The way that I took pictures of those bands in the 80s was exciting because it was the beginning of something, and it was the music of my generation as well.

So what’s coming up for you?

I’ve got another exhibition coming up very soon where I show photography of Noel Gallagher, also in collaboration with Angelo Carnielo. I followed Noel around for 18 months to capture the process behind the creation of his songs. It’s creativity at first hand. Maybe a couple other little book projects also, but I’m not rushing into anything too quickly.

In the early 1980s Lawrence was commissioned to document the emerging New York hip-hop scene and his portraits of legendary artists from that era include Run DMC, Eric B and Rakim and Public Enemy. Lawrence has worked with some of the most famous faces in the business including legendary artists such as David Bowie, Blur, Morrissey, Grace Jones, Pet Shop Boys, Paul Weller, Oasis, Ian Brown, Ramones, New Order, Eurythmics, LL Cool J, Pulp, Snoop Dogg, George Clinton and James Brown. Besides his projects in London, UK, Lawrence told us about his wish to work with German artists and musicians in the near future. We hope to welcome him in Berlin one day.

His exhibition ‘Lawrence Watson photographs Noel Gallagher’ was exhibited at Londonnewcastle Project Space. You can find out more about Lawrence’s photography practice here.

Photography: Ailine Liefeld

Interview: Tim Seifert

Text: Waverly Rose Mandel