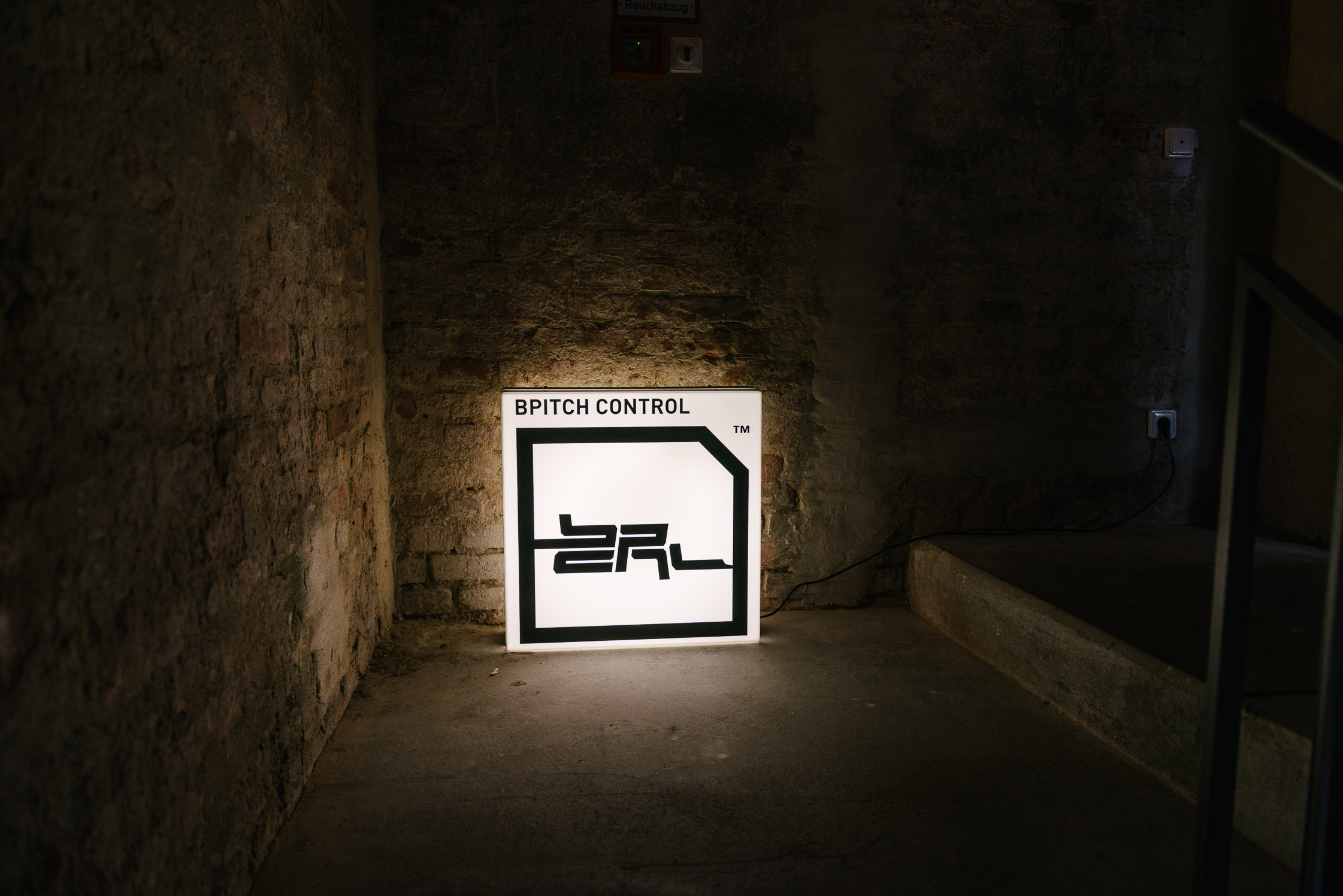

Much of Berlin’s rollicking techno and club culture owes itself to the musical pioneers of the early 1990s and 2000s. One such visionary who still effects a remarkable influence today is the artist, producer, and founder of BPitch Control records, Ellen Allien.

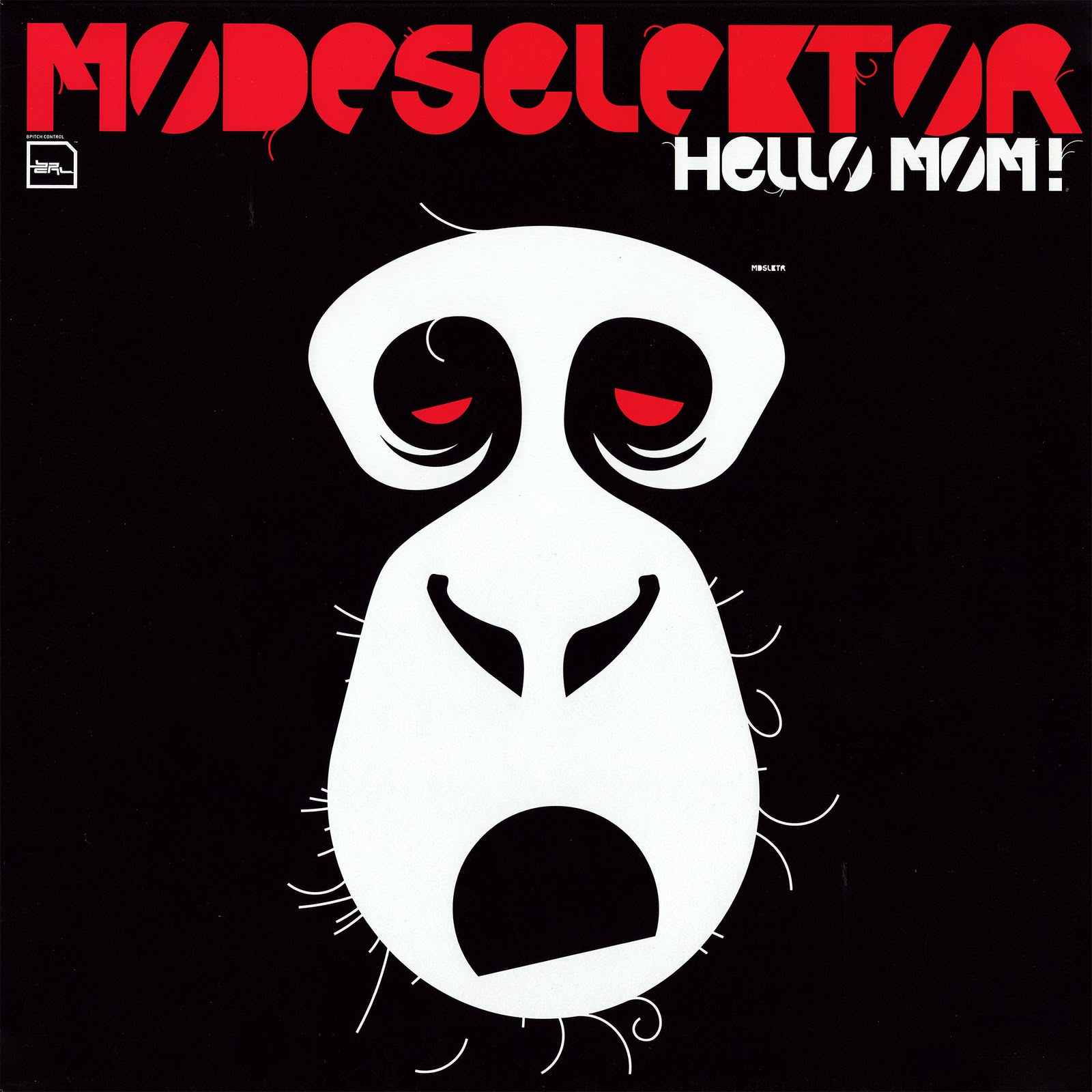

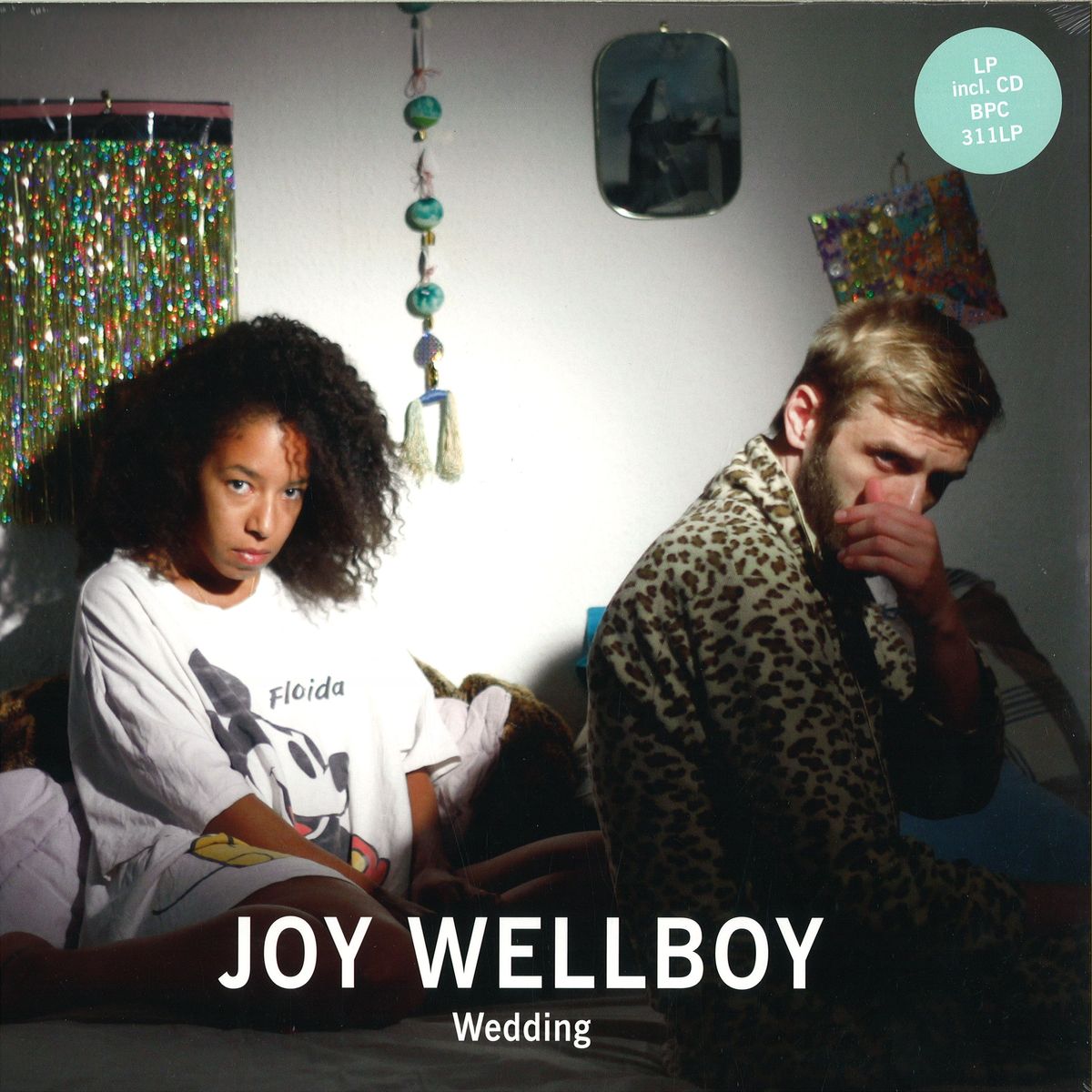

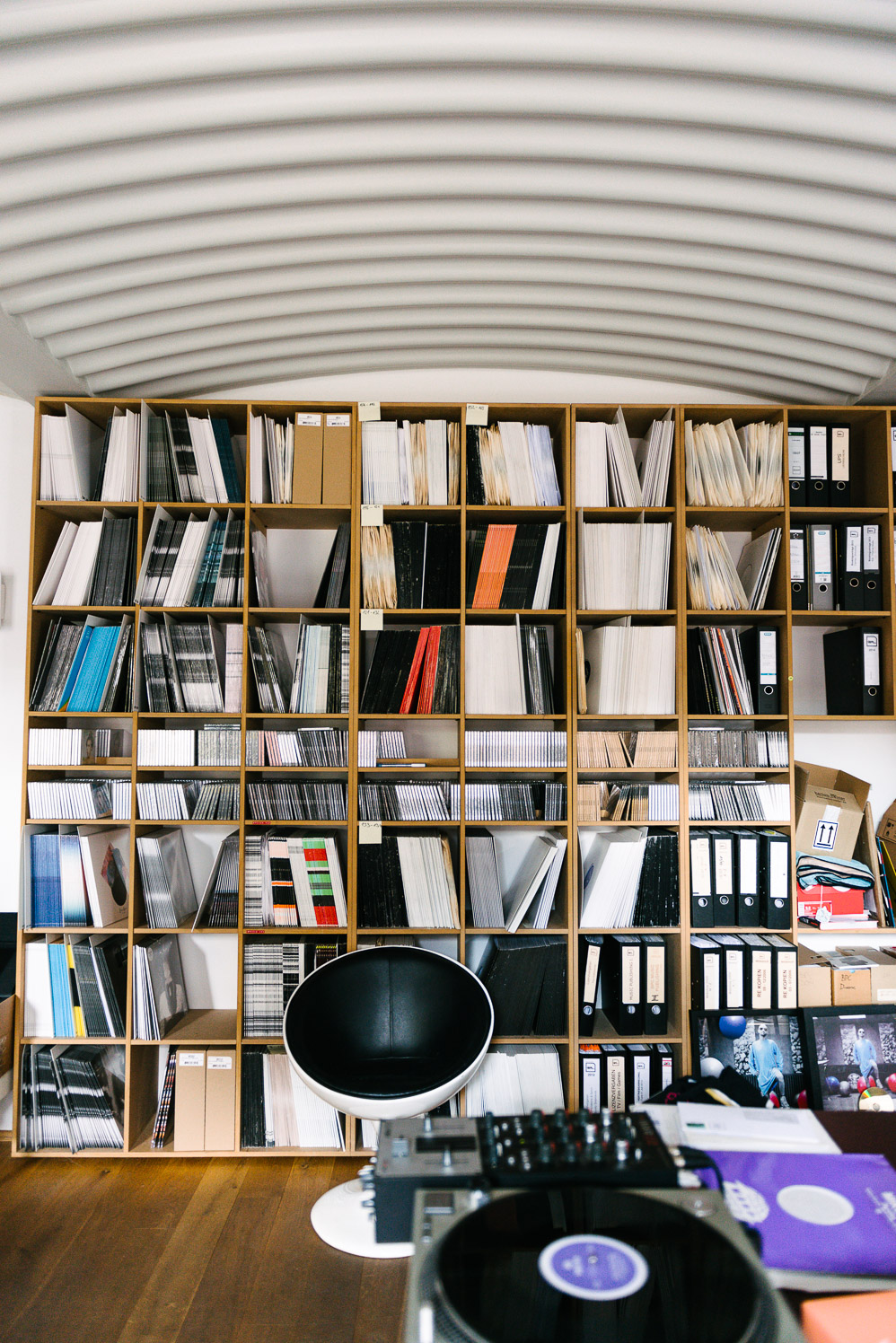

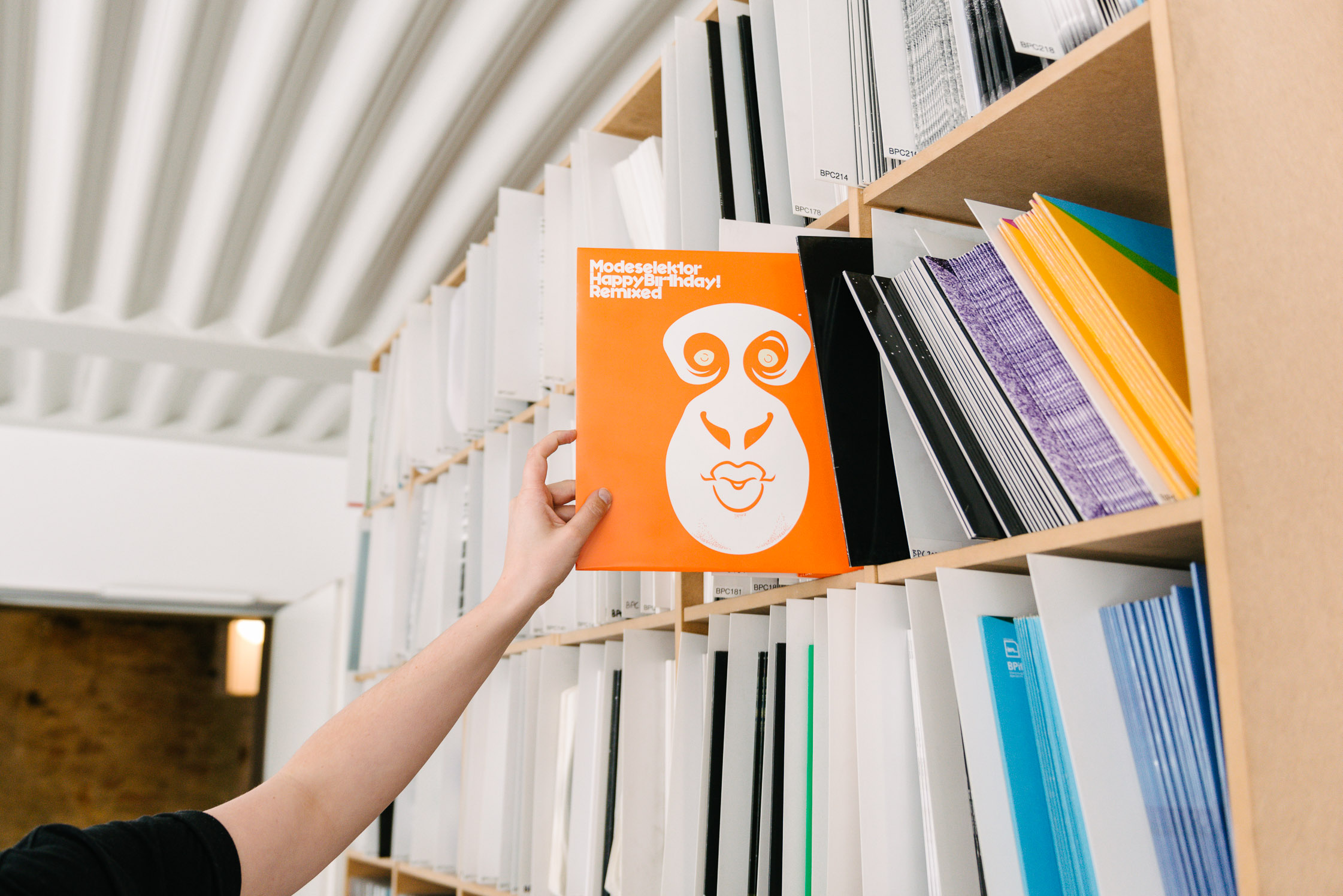

Ellen played a key role in transforming a small, localized phenomenon into an internationally celebrated movement. Her artistic drive is stronger than ever: She tours frequently and releases regular albums to consistent critical praise. Since 1994, her label has grown from a host of underground parties to a figurehead of Berlin techno, home to more than 50 artists, including Apparat, Telefon Tel Aviv, Modeselektor, and Dillon. But much of Ellen’s current success belies years of hard work, persistence, and self-belief—a long struggle that began in a divided city and blossomed amid the cultural and political revolutions that sprung from the rubble and dust of the Berlin Wall.

This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online. Head over to ZEIT Magazin Online to see more images and further insights on Ellen.

“As a kid, and all my life until the Wall came down, I felt I was in a cage.”

Ellen grew up in West Berlin, an island of democracy totally contained within the communist GDR. Tensions in the city were high and the continuous threat of war dominated daily life. “Growing up, I remember playing in the forest directly by the wall,” Ellen says. “As a kid, and all my life until the wall came down, I felt I was in a cage. I mean, I could see the watchtowers. Newspapers and fliers in the street were always talking about military things: tank training, shooting practice. The Second World War had a great effect on us.”

But out of this tension arose an unexpected side-effect. After the Berlin crisis of 1961, which saw Soviet and American tanks face off at Friedrichstraße’s Checkpoint Charlie, many West Berlin residents fled the city for the more prosperous and the less volatile West. In response, the West German government subsidized housing in the city to stymie the flow. Young students, drifters, artists, and musicians flooded in to occupy apartments that now lay abandoned.

“When I was 18, I lived in a squat in Schöneberg for five years,” Ellen says. “It was this loud, colorful place—full of artists who were political. I learned how to live without pressure and fear. Being away from my parents, finding myself, I didn’t worry so much any more about my future. I tried new things and new ideas. I went to acrobatic school, and dancing school, for instance, and then I worked in a record shop.”

It was around this time that Ellen’s musical talents began to emerge. She’d taken guitar, singing, and piano lessons as a girl, but it wasn’t until she met her first boyfriend at the Schöneberg squat that she started experimenting artistically. “My boyfriend had some turntables,” she says. “I bought old records and started mixing and making demos. At the same time, he was recording and producing bands in the squat where we lived—black music, a type of sound I’d never heard before.”

Creativity and freedom were common in West Berlin’s squats during this period, and this exuberant atmosphere was about to spread across a reunified Berlin. After an on-air flub by a misinformed East German spokesman during a televised interview in November 1989, thousands flocked to checkpoints on both sides of the wall, believing that travel restrictions had been spontaneously lifted. As Eastern soldiers stood around scratching their heads over the ambiguous directive and made frantic phone calls higher up the chain, the crowds surged forward, crossing the border. Within hours, men and women were hacking the wall to pieces with mallets and sledgehammers and dancing in the streets. Twenty eight years of prison-like confinement had come to an abrupt and euphoric end.

“When the Wall came down, the club scene had space. There was freedom to be ourselves.”

“When I heard the wall had fallen, I rode my bike through the East to see what it was like. It was incredible—all the places and people I’d never seen before,” Ellen says. The Berlin youth were filled with optimism, and Ellen and her friends started going to underground parties in the West and newly opened East. “The early clubs were a meeting point for a new generation who were trying to find something creative. There was an amazing intellectual and music scene in the East using early electronics, though it had been controlled,” she recalls. “Young people from the East and West came together for the first time at these parties and discovered new lifestyles. When the wall came down, the club scene had space. There was freedom to be ourselves. The music was the music of the zeitgeist: it wasn’t rock anymore; it was electronic.”

“Back then Dimitri Hegemann, who later opened the club Tresor, opened the UFO club and Fischlabor bar in Schöneberg,” she continues. “I started working at Fischlabor because it was in my neighbourhood. I didn’t work there because of techno; I started working because I needed to pay for school! I was studying acrobatics, dancing, acting, and art. I needed a night job and this was a real night job. That’s how I met all the DJs on the scene at the time and how eventually I started DJing publicly myself. Everybody was there—it was the meeting point for the future musicians of the scene.”

The radio station Kiss FM asked Ellen to host a radio show focusing on this new wave of music. It featured local artists and innovative stunts, including live broadcasts from the now legendary Tresor, housed within a cavernous, disused power plant. The broadcasts featuring house, techno, listening, drum n bass, gathered steam and went on to become Ellen’s first record label, Brain Candy. “It was very abstract,” she muses. “I signed on friends and musicians that I found interesting. We had no money, but it was fun. My distributor, however, disagreed. He was more into commercial music and wanted to change the sound, so in the end, I chose to close it down.”

Brain Candy’s failure was a sign of the times. Despite the initial success of the Berlin club movement, the original venues had lost their way with commercialized music. Many clubs were forced to close because they lost their locations due to gentrification. That’s when Ellen took the initiative. “I started BPitch Control because there was a need: to keep the music alive. Many of the pioneers were tired and had left the club scene. I thought, ‘If I don’t do this, who will?’”

With clubs closing down, Ellen threw a wave of new parties that recruited new artists to the BPitch Control banner. But reviving the club culture was fraught with hurdles. “There was no-one to teach me how to do it,” she says, “so I had to learn along the way. I lost a lot of money and wasn’t playing so often. There was a mafia in the East at that time and they would take money from the promoters and hit them and so on—it was quite raw!”

She also faced challenges from within the techno scene itself. “I think as a woman if you have new ideas and you are cute, men can sometimes be jealous. But it’s always like this, whether you’re an actor or a painter or whatever. There were, of course, the discussions back in the day, ‘Can she mix? Can she produce?’ But you have these discussions about men too.”

Ultimately, Ellen’s distinctive musical voice spoke for her. Her first albums, Stadtkind and Berlinette, were released during this period and had a great effect on local musicians. The dark, glitchy, and original aesthetics demonstrated a deep connection with Berlin and cemented her position in the burgeoning techno scene. This was the time when Ellen started to gain international recognition and Berlin and its club culture were hyped all over the world.

Ellen’s produced a further six albums, with each record approaching Berlin from a different perspective. “I work with different synthesizers on each album,” she says. “The collaboration with Apparat [on 2009’s Orchestra of Bubble] was very poppy and upbeat, which reflects the strong bass lines of the Moog synth we used. After that, I was tired of the Moog and started looking for an ARP. The next album was Sool, which was melodious, but in a minimalist way. My sound changes over each record, but the way I write my lyrics brings them all together with a common theme. I have a lot to say about things in my life, and people can interpret their own meaning from what I sing.”

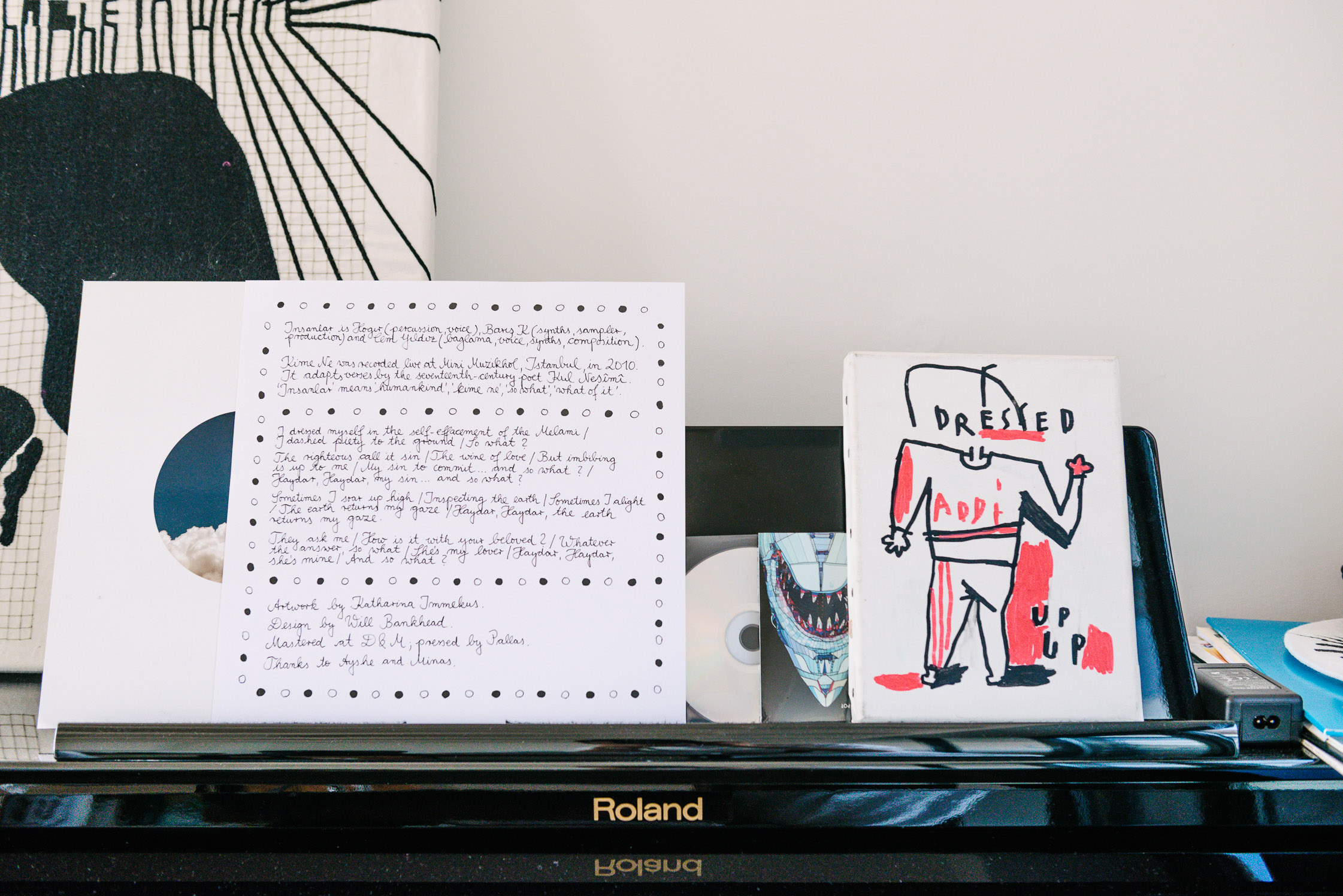

At Ellen Allien’s label and artist agency BPitch Control

“People mourn legends of the past, but those underground clubs still exist today!”

One interpretation would see Ellen’s music as a reflection of the evolving scene and city she helped to shape. She was born in a divided Berlin, witnessed its reunification, and was at the forefront of a new musical movement that celebrated freedom and openness. While some Berliners lament recent changes, like the recent increase of tourists and expats, Ellen’s outlook is overwhelmingly positive. “There are many things about the world I’m not happy about: people using religions to fight wars, my neighborhood being full of H&Ms and Zaras; but Berlin is still really vibrant and exciting. It’s drawing new crowds, new musicians. The clubs still have space and licenses. There are spaces here for people that don’t have space in other cities. Many outsiders, like gays and transexuals, come here and feel at home. I play in so many different clubs, not just the main ones, small clubs too—there’s so much going on!”

And having been there from the start, Ellen is quick to remind critics suffering from nostalgia that Berlin’s club scene wasn’t always so strong. “In the past not everything was better. The music scene is much better now. It’s not true that the club scene is bad or dead—it’s just not true. There are clubs with no rules here that are open all day. People mourn legends of the past, but those underground clubs still exist today! They like to complain but they don’t do anything about it—because, if you ask me, they don’t have the eggs!”

Thanks, Ellen, for sharing your remarkable story and for helping to make Berlin’s techno scene what it is today. Check out Ellen’s website for music and tour dates and BPitch Control for more interesting music artists.

Text:Jack Mahoney

Photography: Daniel Müller