Guilherme Coelho doesn’t care for aesthetics — at least not where his work is concerned. His take on architecture speaks to the heart, not the eyes, valuing life-changing impact over superficial notions of beauty. Operating in underdeveloped nations like South Africa, Lesotho, Afghanistan and Yemen, Coelho constructs healthcare facilities with a remarkably simple approach.

Based in Berlin, his Prenzlauer Berg flat is charming and clean, if unassuming in its look; what stands out is the sound of Samba music filtering in from the kitchen, the smell of something spicy on the stove, and the vibrant photos of children dancing that hang in his foyer. “I took those in Mozambique,” Coelho tells me from the kitchen, raising his voice to be heard over the music, “I’ve been working with Medecins Sans Frontieres in Africa, and it’s shown me a completely different world, literally!”

Coelho likes to keep things simple. Simple flat: plain white walls, washed wood floors. Simple setting: we talk over cups of hot spiced tea. Simple lifestyle: school, family, friends, work. He’s not one for excess, and it quickly becomes clear that the value he places on the simple things comes from his true passion: his work.

“I fell in love with healthcare architecture because it’s very rational.”

Coelho relocated to Berlin from Brazil in 2014 to complete his PhD at the Technische Universität. Now an architect by trade, he specializes in the design and construction of healthcare facilities — hospitals, emergency stations, clinics — a craft that’s taken him everywhere from Sudan to Afghanistan. “I fell in love with healthcare architecture because it’s very rational. The distance between what you think and what I think is very narrow.” He continues, “All the decisions should be based on technical principles, and if you really understand those principles and concepts, you start to understand everything, really.”

He defined the subject for his PhD after visiting Mozambique with the Medecins Sans Frontieres (MFS): “I’ve seen so much. I’ve learned so much. We’re talking the poorest countries in the world. I decided to focus on infection control because from what I saw in Africa and from my contact with the doctors out there… It’s popped up as the issue. The most important thing.”

In between bouts in Brussels working at the MSF headquarters, and stays in Kandahar, Coelho’s work, both with MSF and later with the International Committee of the Red Cross, brought him to low-income countries where he has had a hand in various humanitarian projects.

In the 2014, he helped design an emergency annex at the Mirwais Hospital in Kandahar, a center that has doubled the hospital’s original operational surgical capacity. 2009 saw his participation in the first temporary, then permanent medical facility in South Sudan, during the peace agreement between the north and south.

He’s worked on field operations in South Africa, Lethoso, and Yemen, to name a few — talking with Coelho about his various accomplishments is intimidating to say the least. But despite it all, he remains steadfastly modest, insisting that the feature we’re working on together keep his work, not his profile, as the main focus.

“I’m much more involved in the planning stage of these projects. I organize, I take all the considerations and fit them into the design. But at times, I’m also involved in the actual construction and logistics,” Coelho explains of his in-field work. “Sometimes, we’ll go in for a short time to build a temporary facility like we did in South Sudan. We only have about three months to do the construction, and we use pre-fabricated materials. You need quick solutions to the problems sometimes.”

These quick solutions mean that more often than not, Coelho and his teams’ designs are purely functional: architecture as we tend to think of it plays little to no role in his conceptions, even when it comes to permanent buildings. He smiles when I suggest that it’s kind of the “anti-design” design.

“The question is less about how to make a beautiful or elegant building, and more about how to build something that is functional,” he says, “We have to think crucially about what materials are available locally. How a specific culture approaches architecture in these developing nations has little to do with aesthetic decisions or being concerned about the beauty of certain materials. It has to do with the technical solutions they’ve found to solve their own problems.”

Becoming ingrained in the culture in which they’re building is essential to Coelho’s cause — the study of infection control in underdeveloped and low-income nations. “Today, we know that the most important thing in controlling infections is the hands,” Coelho remarks, “It’s very important to understand how each culture understands hygiene, because if you understand that, you can improve it.”

Hospital Project in Afghanistan

One of the projects Gui has completed with international Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC)

This is a process that deeply affects the way that Coelho approaches his architecture, arguably the most important step in a pre-construction plan. Where some architects would consider artistic or symbolic significance, Coelho’s concerns are more literal. “Usually it takes some time to understand the local culture. You need to understand that each place is different, and especially that these countries have values and ideas that are different than what we have in Europe. That means there is a different way of providing healthcare,” he explains.

“Culturally speaking, we need to consider how people behave. This is important in the design and setup of the building. Technically speaking, we have to think about everything from what technical equipment they have access to, to how they build things here. It’s very important to use local knowledge because in the long term, the people of this culture will be the ones to fix and maintain these buildings.”

“There is a kind of basic five things that human beings need in life: security, water, shelter, food, sanitation. Beauty? That’s something extra.”

What does this mean for his designs? Function over form. “There is a kind of basic five things that human beings need in life: security, water, shelter, food, sanitation. Beauty? That’s something extra,” Coelho continues, “When we talk about those five basic needs and we say shelter, we don’t mean a beautiful home. It’s just to have a roof over our heads. For the wind, for the cold, for the weather… For protection.” In practice, this concept means that workers like Coelho need to keep certain considerations in mind: absence of wastefulness (as some materials might be in short supply), using local building techniques, and practical design. “Expats sometimes come in to make a project and they try to bring this mentality of beauty and design and buildings that look ‘cool.’ I don’t judge. But for me, it’s not the priority.”

“I made and I saw a lot of mistakes. Of course, it’s something new for all of us and something very new for me,” Coelho notes when I ask about the difference between design in the Western world, and design in underdeveloped nations. “I’d never in my life before had to build a building that generates smoke, for example. But in the sterilization units in many African countries, you’ll find that the heat source is wood. The building produces smoke, which actually means there’s a lot of things to consider: you have to be sure that the smoke doesn’t affect the patients, you have to think about waste management, you have to avoid the contamination of groundwater… You’d never think about in a Western or developed country.”

“People find a way to find happiness. This is beautiful.”

In the notes that Coelho sent to me before I visited his flat, a sentence stood out: “The physical environment of healthcare facilities has a direct impact on the quality of care.” I read the sentence out loud to Coelho and it is clear that this has heavy significance for him. “The idea is that we could have much more impact in quality of care in developing countries than we actually could in developed ones,” he notes, “Clinical activities and medical activities, they are so strict in their procedures, so if you consider something like sterilization… This is a process. There is no question, you have to start at A and finish at Z. Every step is essential.

This is actually a kind of production process: you need to create a space that will help you to follow these steps exactly. At the end of the day, the environment can help you to do a better or easier sterilization.” It’s a relatively simple concept — true to Coelho’s form, it seems — but a crucial one. At one point during our chat, I ask Coelho if he has a mantra or motto, words that, like some other architects, he considers ones to live by. (He doesn’t.) They might not be the most poetic, but this sentence, that physical environment has a direct impact on quality of care, is a stark, absolute representation of his design ethos.

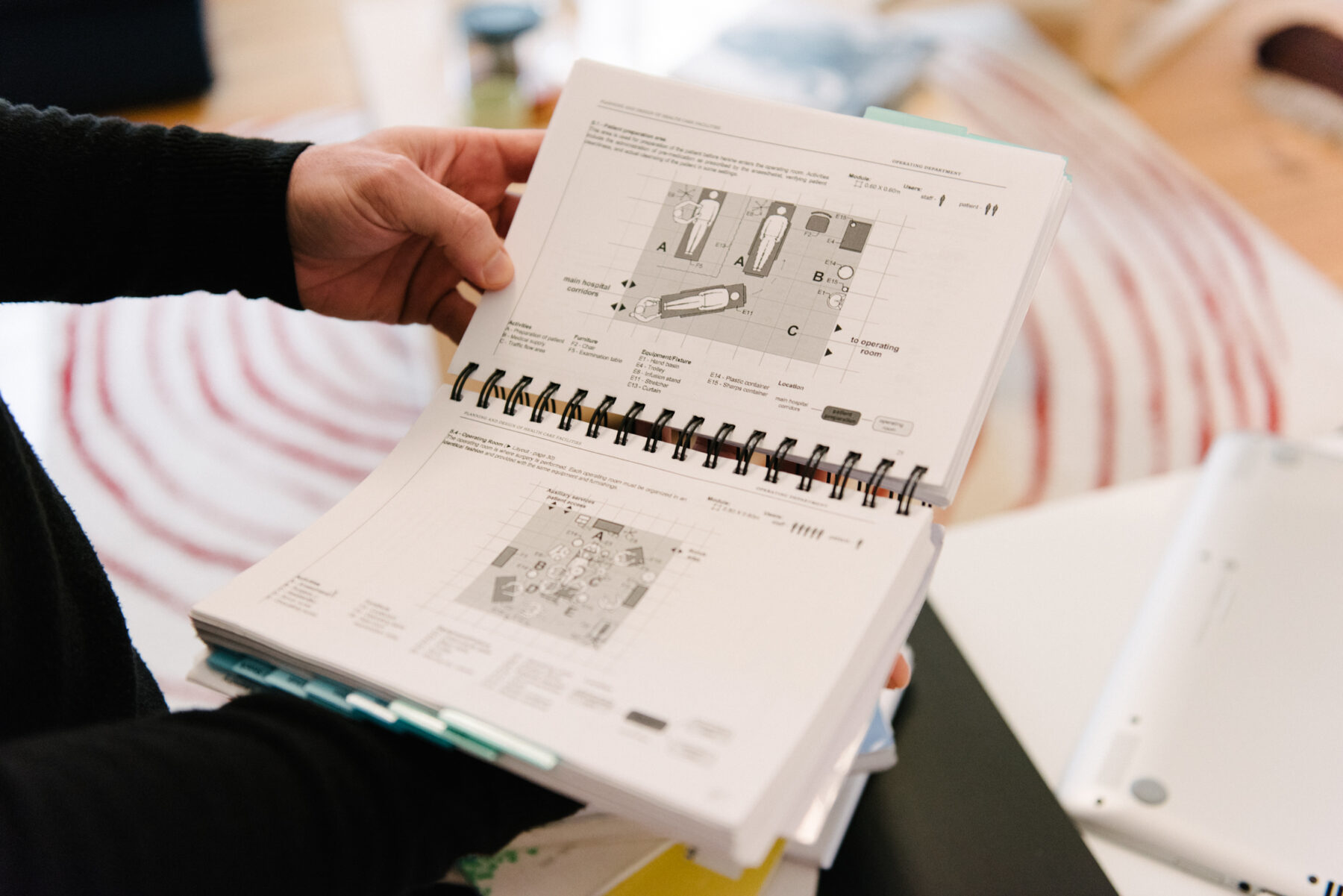

Planning and Design for Health Care Facilities:

The book Gui developed in collaboration with 25 other specialists

Part way through our talk, Coelho pulls out a book. It is plain; unfussy black typeface printed on white pages, spiral bound, with color-coded divider tabs. He flips through it with gusto. It is the Planning and Design of Health Care Facilities, a book he developed in 2013 with 25 other specialists and the MSF. It acts as a guide to professionals involved in his field, providing recommendations intended to improve the standards they so dutifully adhere to.

If at any point it seemed like Coelho’s field was a “niche” one, the book proves that this cause is much bigger than it seems. “This domain doesn’t get a lot of attention,” Coelho explains. And yet, he is, of course, able to remain positive: “But the good thing is that it doesn’t have a lot of money pumped into it. That means that there’s not a lot of sophisticated technology, there’s no high-pressure, low-pressure buildings, ventilations, so it takes out a layer of complexity, and actually makes our jobs easier.”

“If there’s anything I’ve learned working in this field, it is that there is no worse problem in the world than war. Conflict. This is the worst that could happen to any person,” Coelho continues, “Yes, my job at times makes me feel very sad. I don’t have much hope for the near future where this is concerned. For right now, I’m not very hopeful that things will change for these nations.”

I had planned on asking him about melancholy; the idea that beauty can come from the ugliness that he mentioned. “The world is a very big place,” he says after a moment, “There is so much beauty in the world, and also so much suffering. For example, when I took the pictures you saw in the hallway, it was during a huge festival organized by the United Nations in Mozambique. They invited all the representatives of this culture from different countries, and they all met at the village that I was staying in. It made me realize that we are not just treating HIV patients or people who have been affected by war or conflict. We are keeping this culture alive. This was something amazing, it was the first time I’d seen beauty in the work that my organization does. You know, it’s not just people suffering and atrocity and saving lives. Yes, of course, it’s this, but it’s people actually living. And not just living: celebrating.”

Snapshots from Mozambique: 2007

“We are not just treating HIV patients. We are keeping this culture alive.”

For Coelho, beauty comes in forms sometimes far removed from the beauty that we’ve defined. He waxes nostalgic not on the romance of architecture or the allure of design, but on how his buildings are bringing to light the beauty in the cultures he’s helping to prosper: “People find a way to find happiness. Compared to the standard of life that we know, looking at them, seeing how they manage to smile and be happy… Sometimes even happier than we are. This is beautiful. This is a beautiful thing.”

Thank you, Gui, for inviting us into your home, and letting us in on the history of some of your fascinating projects.

This portrait was produced with the support of concert promoter and artist agent Scumeck Sabottka.

Berlin never ceases to amaze us – it’s one of the cross-roads of the world. Spend hours exploring the projects of its fascinating inhabitants.

Interview & Text:Emma Robertson

Photography: Robert Rieger