His friends just call him “Doc,” but, much like a mad professor, it doesn’t bother Florian at all. When we meet with him in his immense old building in the middle of the 9th district of Vienna, his neatly tied-back hair gives him the air of a successful young entrepreneur. This isn’t entirely untrue. After completing his doctorate in biology, with a focus on spider research, Doc lead two companies to success. With the first he concentrated on the sale of niche analog products, but in the end, everyone jumped for one product: Polaroid film, which at the time was barely even available.When Polaroid completely stopped the production of instant film, together with two partners Florian overtook the last working factory of the company in the Dutch city of Enschede and with The Impossible Project, began to produce the film again. After a few busy years he decided to operatively withdraw from the project and dedicate himself to a new project in his hometown of Vienna again. He discovered the most beautiful business location in the city – in the form of a palazzo built in the Venetian style in the center of the 2nd district. It’s the ideal location to realize his concept of a world of analog experiences for the senses: Supersense.This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who presents a special curation of our pictures on Zeit Magazin.

How does one go from studies in biology to being an entrepreneur?

My time in the sciences was one in which I was experimenting and tinkering, for example, how electrodes are implanted in spider’s eye muscles. But pretty quickly my grandmother asked a pretty big question, she said, “I’m proud of you and what you’re doing is great, but how do you want to earn a living? What does anyone need this for?”

After a short attempt at getting a foothold as a scientist, a friend told me that I should apply for a job as an Internet project manager – this was in 1998, and the Internet was just beginning to come together. In the beginning you could become an Internet project manager if you could write your name correctly.

I thought to myself, “Okay, why not?” I really got some offers, including from the Lomographic Society, where I had a crazy job interview. They said, “Good, you know about spider’s eyes, these are optical systems. We need someone to market 10,000 night vision devices, which are also optical systems.” And I got into the field of photography via the Lomographic Society.

Was it logical for you to stay in the same field?

What I realized with the lomographers was the fascinating possibilities of inspiring people all over the world for something. I specialized in this, I built up the online shop and community. Later, I wanted to create something independently and dared to take a step away from photography.

This didn’t work out so well: shortly afterwards I founded the company Unsaleable. Our goal was to again excite people for products or goods which have an analog quality, but no longer seem to be relevant. One of our products, instant film, was above the others. Relatively quickly we began to only sell instant film.

Selling analog product over the Internet, was this a form of opposition?

No. I think it’s a brilliant combination. For a long time everyone thought that the digital would wipe out the analog. Yet, I believe that it’s become clear that the combination of both is perfect. The digital gave the analog a new chance. What’s exciting is that now the younger generation, who were raised with the digital, are the most excited about analog and for the continued development of analog worlds.

Why?

Through the digital everything is accessible, but somehow behind a glass window. You can’t touch it, you can’t smell it, and this is precisely why a new awareness for analog has taken place. Additionally, the digital gives all these niche products and producers a huge opportunity, because they can sell to the entire world from a small location or workshop. For me this is a positive and beautiful symbiosis.

What is the major difference between analog and digital? Is analog automatically better?

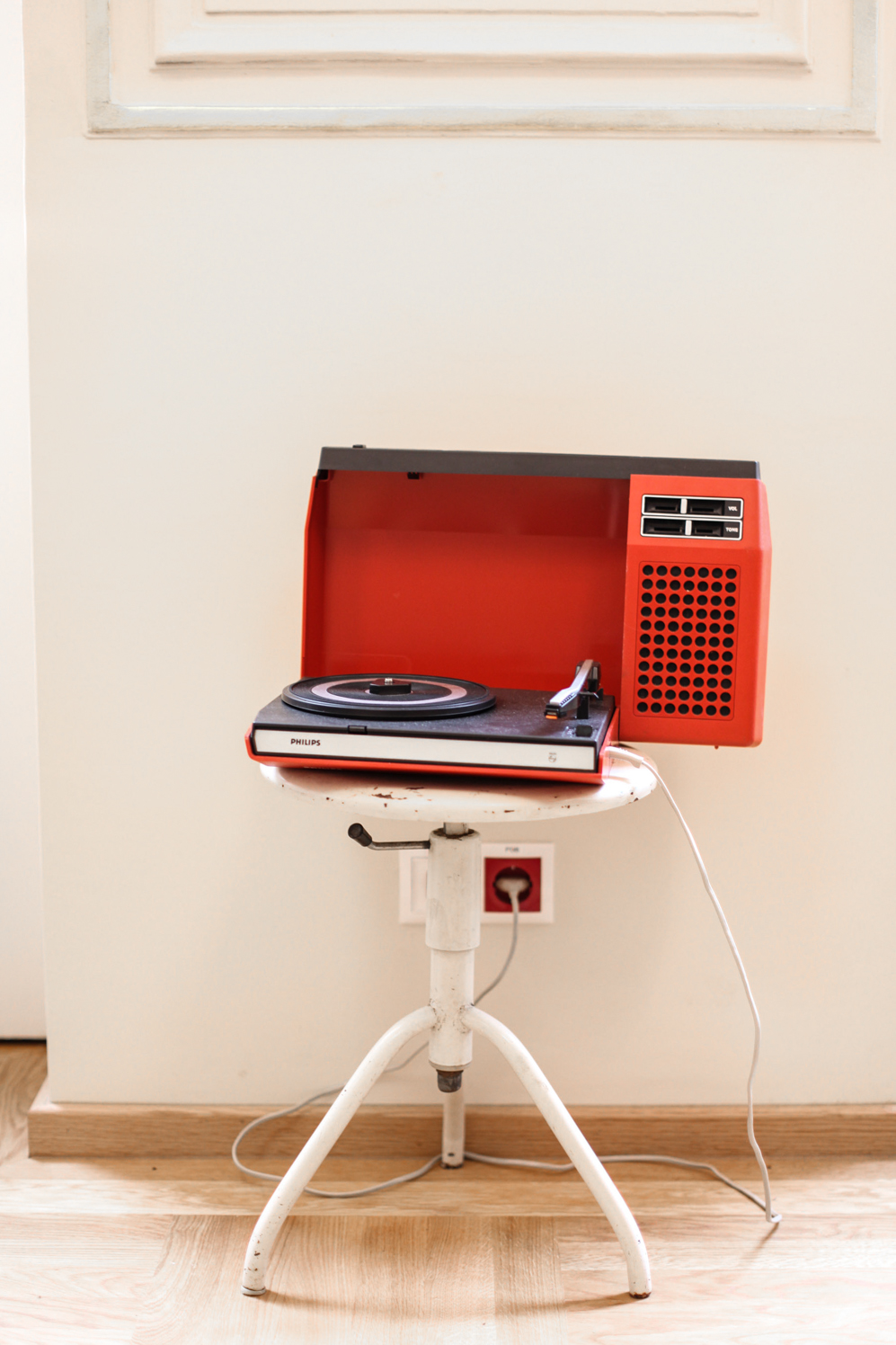

I wouldn’t say that, I’m not a religious “Analog-ist.” I believe it’s about the multi-sensory. You can grasp the analog, you can smell it, it’s there, it’s real, it’s unpredictable, it always feels warmer. These are organically grown, chemical reactions that are simply closer to reality. For me the digital is more superficial. Of course it’s faster and this also has its advantages. Perhaps this fits well as an example: When you’re driving in your car or out and about, you hear music as an MP3, or on a CD. But when you come home, prepare a nice meal, drink a glass of red wine, then you put on a record. This has more depth, it’s a pause in an increasingly fast world.

You had huge commercial success with the sale of instant film. What did it mean for you when in 2008, exactly on the 60th anniversary of the technology, they discontinued production?

At the time it was extremely painful. It showed that at just that moment that we had the feeling that it was the beginning of the re-discovery of instant film – at the time we had 10,000 customers globally – Polaroid demonstrated a complete lack of understanding for this new niche market.

At the time we signaled to Polaroid that we would, in some way, like to pursue this operation. But they probably thought I was crazy. For a long time there was no response, other than an invitation to the closing of the factory. I immediately went there and got to know the production manager, André, who was supposed to keep an eye on me, to make sure that I wasn’t up to anything. But he told me that there really was a chance to continued production of instant film, and he was excited by the possibility. So I allied with him and eventually we saw the whole thing through.

The Polaroid management thought you were crazy?

Exactly. In all the discussions – we negotiated for over a year – they always said that it was impossible to continue production of instant film at the factory. I told them that I would call the firm “Impossible,” but that they should simply give us a chance to try it. It was clear to everyone: if the machines and the factory were scrapped at any point, there would be no more possibilities to create this product.

It would have been impossible, if not for the FBI, by chance during the negotiations, storming the headquarters and jailing most of the management for tax evasion. As luck would have it, this gave me access to a friendly-minded manager who had the power to sign off for ten whole days. He called and said, “Florian, we have ten days to handle this sale. If you can come up with 180,000 Euros, then we can sign the papers and the factory will be yours.” And, actually, at that point, we already had so many investors on our side, that we could buy the factory and finance its restart.

How did your friends react when you told them, “So, we’re buying the factory?”

They’re used to it. Looking back, this was a very logical step. We had the customer base, we had years of experience in the field, and we knew there was new interest.

I have to say that we didn’t have any idea at the time how complicated and twisted everything would be. Thank god we didn’t! I thought to myself, great, now we’ll produce our own film and we’re independent from Polaroid. In the end, this was just one of the crazy things that my family has been through with me.

As these initial hurdles were overcome, you spent a year trying to find a new chemical composition.

Exactly, that took a year. Really it was sensational, because normally this kind of development process usually takes much longer. But, like I said, I had underestimated how hard it would be. We had great success with expired Polaroid film, and at the time I thought, it can only get better. But our first products were very experimental. There was film that dissolved and film that was extremely overexposed. It was a rocky road to quality – we needed to appeal to a larger customer base outside of experienced and experimental photographers.

Edwin Land, the founder of Polaroid, once said, “Don’t start any project before it’s really important – and almost impossible.” Could this be your motto?

Yes, absolutely. I’ve always been fascinated by things that seem impossible at first glance. To swim a bit against the current. To tell these stories and to excite people for something outside of the mainstream, even if it’s considered impossible or irrelevant – this is definitely something that runs through my life.

In 2013 you operatively withdrew yourself from the Impossible Project. Was the idea for Supersense already there?

It was always there because I met so many other crazies through the Impossible Project and wanted to start something with them. With the Impossible Project, as a serious business, it would have been difficult. I increasingly found myself in board meetings and in front of Excel spreadsheets instead of working with creative people or developing new products. I remain, however, a proud founder of the Impossible Project, it’s an important part of me.

You mentioned storytelling earlier. Is there a story that you want to tell about Supersense?

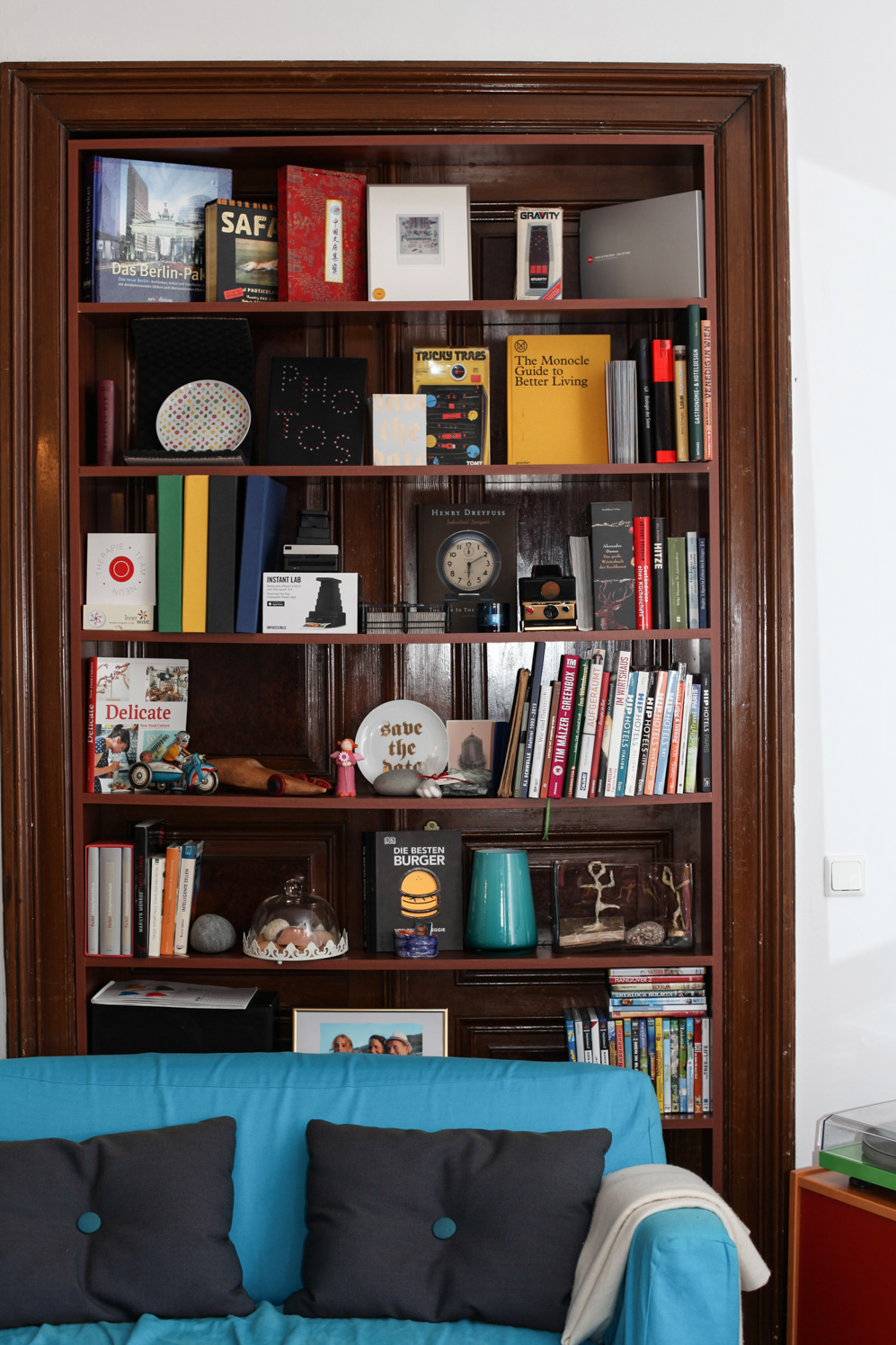

Yes, we have a stage here where we invite people to come and tell their story. Our store has a sort of workshop character, which was more common in the past. Our partners can do what they love, and the customers can’t just buy a product, rather they’re also involved in the manufacturing process. Records are cut here, books and posters are printed, images are made and workshops are held.

I can remember during my childhood going to shoemakers, or these kinds of creators. It smelled like leather there, there you were really close to the production process, it was a sensory experience. With the Impossible Project I saw how all the people who visited the factory had a completely different understanding of the of the product by the time they left. This was the founding idea for Supersense.

Supersense is more than mere storytelling learned from a marketing book, rather it’s always about craftsmanship.

Exactly, there are no machines there that aren’t being used. It’s also not some good looking scene, things are produced there. It should smell like colors, coffee and the acetate that is used on the records. It’s a haptic way of experiencing the world, but not a museum. If it was a museum, then it would have been an active museum. All these things that are there aren’t showpieces, rather really in use. There will always be a young woman or man who will bring these machines back to life and put them into the digital world to present their product and excite people for it.

How do you see Vienna as a basis for such a crazy endeavor? Is it a good place to start absurd things?

Yes, absolutely. In the last few years I traveled the world. I opened stores in Tokyo, New York, London and Paris and through this I’ve learned to really treasure Vienna again. Because in Vienna very, very bizarre, special, and crazy-in-a-good-way things can find a home. Because of this, Vienna is very slow and very proud, many things remain unchanged and through this first digital wave they are being discovered again as interesting, special or valuable.

For example?

Many analog firms that operate worldwide still reside here, for example the Lomographic Society or Peter Coeln with his West/East Light Museum and vintage camera, with which he’s created an incredible monopoly.

Also there are many companies here that have been passed on to a new generation and because of that have taken on a whole new spin. Emblematic of this are the many young vintners in Vienna, who create fantastic, internationally successful products.

There is also good support from the city. Inspiring banks for something impossible or crazy is difficult, but for the creative industries there is great support. Above all the Vienna Business Agencyhas been a great partner and have an open ear for crazy things. At the same time they have strict rules about the economic side of things and I find exactly this combination important.

Would Supersense work everywhere or only here in the 2nd district, on Praterstrasse, in Dogenhof?

The location was deliberately chosen, it has something magical. At the time this building was built, Vienna was crazy about Venice. In Prater there was a “little Venice” and you could go through canals on a gondola. The builder thought it was good and got it in his head to build a Venetian palazzo in the middle of Vienna, with the dream of being able to go from here to the Prater with a gondola.

The location of the Prater fit perfectly, because this was a place of storytelling. The first movie theater was here, the “Woman without an Abdomen,” all of these fascinating stories. And now the Praterstrasse and the whole 2nd district are experiencing a crazy change, and it’s great when we can function as a nucleus.

Apart from spending time at Supersense, where else do you like to go to in Vienna?

For shopping I prefer long-established stores like the Leica Shop in Westbahnstrasse 40 in the 7th district, as well as the Fleischerei Ringl in the Gumpendorfer. When I’m looking for a good meal I go to toma tu tiempo at Zieglergasse 44, in the 7th District and the Swiss House in Vienna’s Prater. The nearby area is also great for walking and jogging.

Last but not least: What is a favorite story of yours, one that you will pass on to your children?

My favorite story is the one of how it all got started. I was at this closing event from Polaroid. This was actually the point at which instant film should have been laid to rest and where my battle would have been lost. And then everything was different and this moment changed an end into a beginning. It changed my life.

The conclusion is that you should never give up hope. Even seemingly hopeless situations can provide insane potential. The unlikely is sometimes actually possible.

We thank Florian for the interview, the excellent espresso and that we were able to enjoy his apartment in the 9th district of Vienna as well as his new multi-sensory world, Supersense. It can be admired in person at Praterstrasse 70 or online here.

This portrait was produced in collaboration with the Vienna Business Agency and its creative center departure. You’ll find more portraits and reports from Vienna’s creative scene here.

Find more stories of creatives in Vienna here.

Interview: Markus Krennmayr

Photography: Martin Stoebich

Video: Nikolaus Sauer