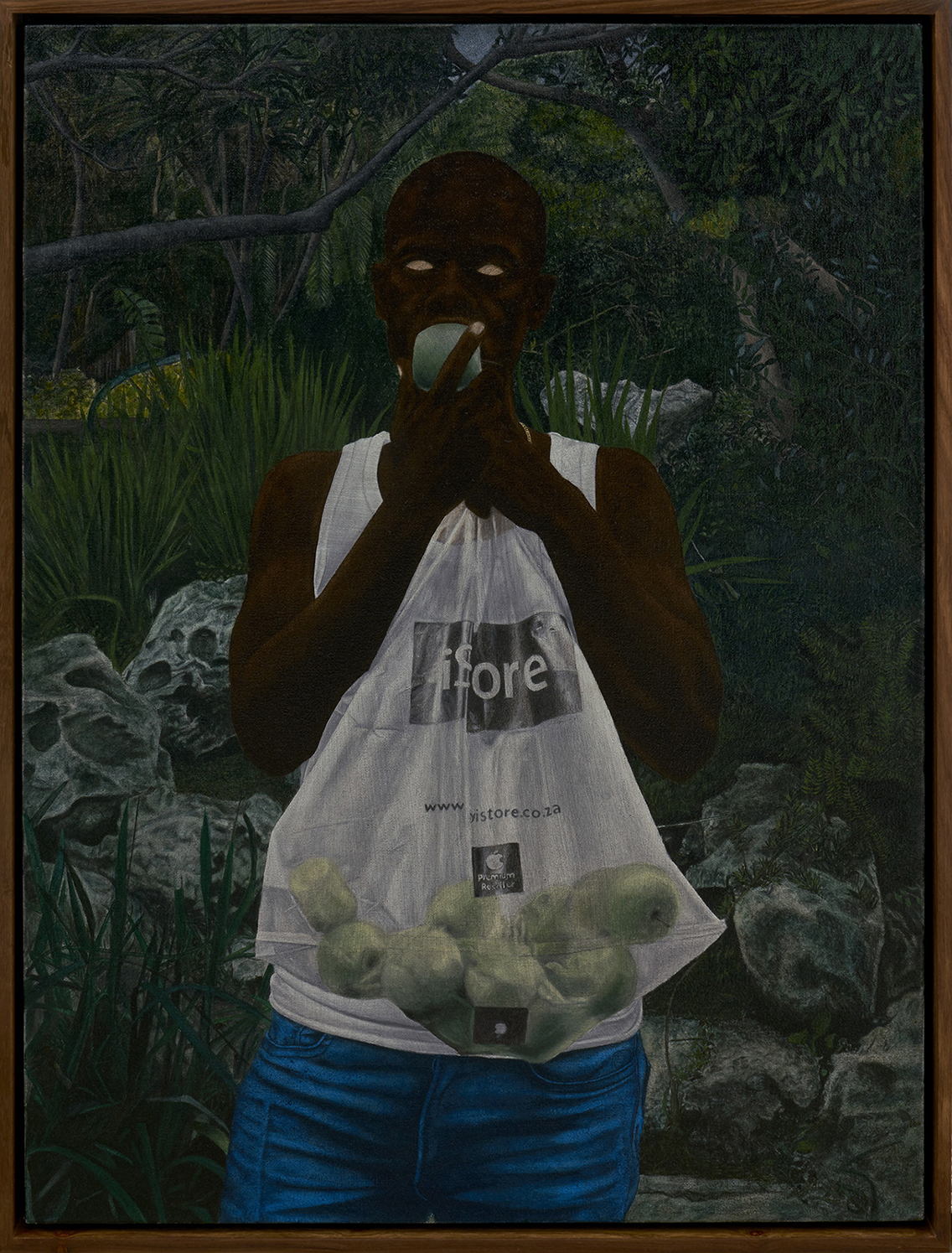

South African artist Cinga Samson was born in 1986 under apartheid. Having grown up in a small town on South Africa’s remote Eastern Cape, he has emerged in recent years as an increasingly influential painter known for his otherworldly yet realistic portraits of young black men in contemporary clothes, posed against deep-hued backdrops of tropical ferns, flowers, and rocky shorelines.

In this episode of the Friends of Friends podcast, Cinga joins Saskia Miller from his home in Cape Town for a conversation about how he developed his trademark style and what kind of legacy he wants to leave with his artwork.

Below are a selection of highlights from the conversation, as well as related links where you can find out more about Cinga’s work.

This episode is part of the FF archive introducing the FF Podcast, a series dedicated to exploring the stories behind the creative changemakers in our community.

On getting into art

“Kids are very creative. Somehow I never lost that. When I was 20 or 21, an artist from a local studio here in Cape Town asked to look at my drawings, and then he gave me paper to do more. I took that as an invite. The following day I brought boards, plastics, and materials to work with: I didn’t own any paints at that time. I was ready to work and be part of the studio space. This wasn’t negotiated, I didn’t ask permission. I had many plans to do different things with my life, and I had applied to many different schools. But when I walked in that studio it changed everything. That was all I wanted to do. I became obsessed.”

On artists that he admires

“At first, the three artists in the studio I worked in… were like gods to me. They seemed to know everything I wanted to know. I had never seen oil paints before, or so many different types of brushes in real life. At that time, I didn’t know many other artists from outside, or even inside, South Africa. But I had this book on Francis Bacon, and he just grabbed me. I was mesmerised by him. He still has a hold on me even now.”

On his time at Stellenbosch Academy of Design and Photography

“I did a one year course, I received a scholarship for underprivileged kids. It was the first time I went into a space with mostly white South Africans. I started to feel different. I started to be aware I was Black. It wasn’t necessarily that people were being racist, but I could just see the difference in resources. I had to travel a long way to get to school, whereas almost all of the other kids were driving. I felt like life wasn’t embracing me, even though I was at home in my own country. So I made a show, Lord forgive me for my sins ’cause here I come, feeling betrayed, somehow.”

On portraying young Black men

“I made a decision when I turned 30 to celebrate, embrace, and honour my life, even if no one else would. Most of my paintings are portraits of myself. I never intended to depict myself. I just couldn’t afford a model. But I could see myself in the mirror, and I fitted what I wanted to portray.”

On including references to luxury brands in his work

“The bags, the brands, the sneakers, the Versace shirts, all of these are included as a desperate cry to be noticed. They’re a means of saying: notice me, I’m cool, I’m something special. Do you see me?”

On leaving his figures’ eyes blank, without a pupil or iris

“When portraits don’t have pupils, you’re not sure if they’re looking at you or not. I really enjoy the feeling that the figure is completely aware of your presence.”

On religion and spirituality

“I don’t think much about my ancestors. I’m not religious. I need more proof of an afterlife. But I do respect the fact that the African continent is convinced that there is one. I’ve had many superstitious encounters and things that I can’t explain. I know there’s more to life than the physical experience we are having. I want my paintings to encapsulate that. I come from people who are strong believers in other dimensions. How can you tell the story of this continent without touching on those beliefs? You can’t.”