The Canadian designer on modernism, systems thinking, and how his thirty-year career in architecture informs his fashion pieces.

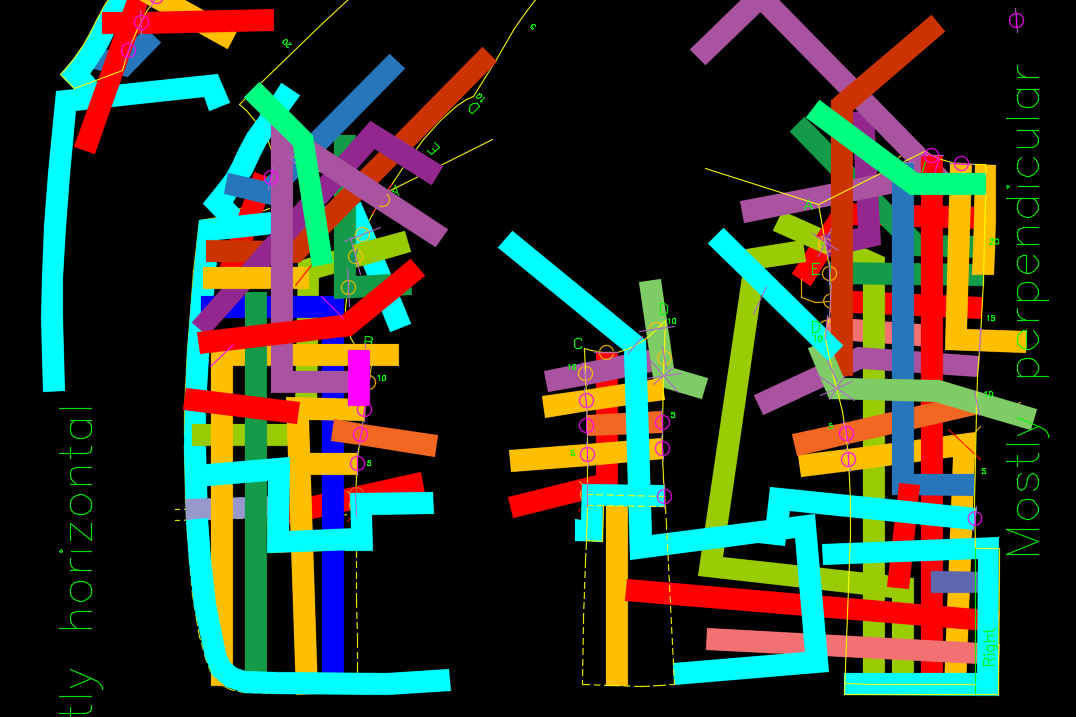

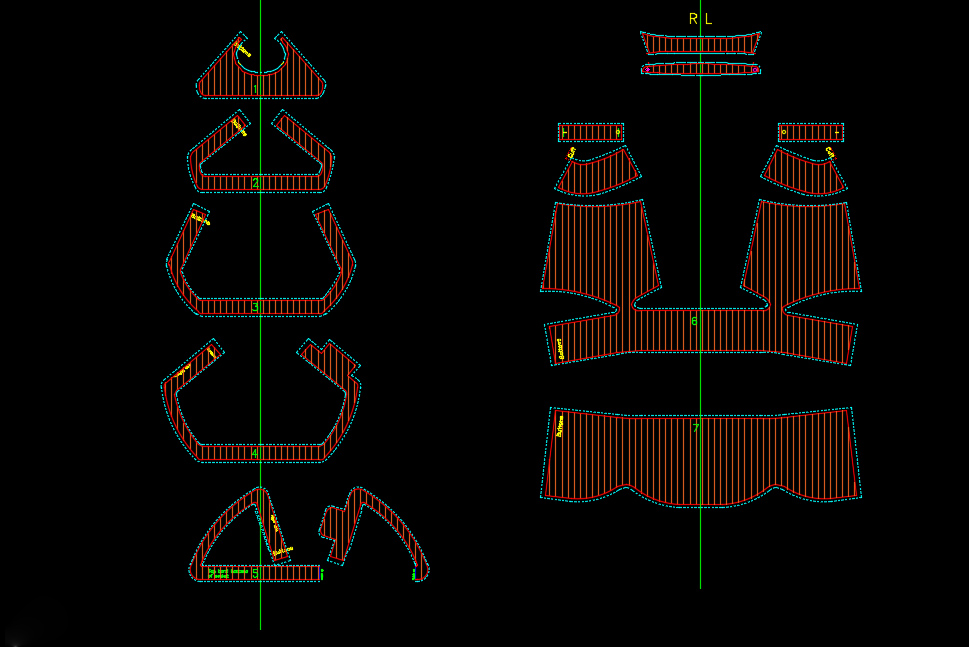

In the back room of his bright fourth floor apartment—aptly located close to Kurfürstendamm, one of the biggest shopping streets in Berlin—designer Mark Krayenhoff van de Leur is busy constructing his garments. Binders full of drawings spill out onto the table, bright patterned swatches pop from the wall, and on a laptop, busy colorful lines form abstract shapes—pieces of puzzles waiting to be formed. The half completed Jacket 3 – Basketweave, composed of perpendicular strips of fabric tape, hangs on a mannequin waiting to be finished. This is a precise design process in action. The Canadian designer’s garments come to life through a distinctive method informed by an over thirty-year career in architecture.

“I always felt like the weird one, like I didn’t quite fit in, like nobody got me,

and I had to sort of hold myself in.”

Krayenhoff van der Leur’s workspace is set up in the home-cum-studio he shares with his husband, the artist AA Bronson. They moved together to Berlin from New York City in 2013 on the occasion of the DAAD Fellowship offered to Bronson, a one-year opportunity to create new work in Berlin. What was first intended as a work sabbatical, turned into a new permanent home. “Compared to New York, Berlin feels much more human, and human value feels so much more important here,” says Krayenhoff van der Leur of the move. Towards the end of the first year, the couple decided to indefinitely extend their stay. Leaving behind a 30-year-career in architecture, Krayenhoff van der Leur found himself stimulated by a new passion: sewing and garment making. He first began sewing when Bronson commissioned him to make the Folly Tent as part of his performance Tent for Healing at the Stedelijk Museum in 2013. Half architecture, half gown, the tent is a structure created for no purpose, rigid from the outside but gauzy and magical on the inside, like a porthole to another world. According to Krayenhoff van der Leur, Berlin is a wonderful space for ideas to grow and for healthy collaboration to develop. “In retrospect, I feel so much about New York life is the worship of money and power, which can be so distorting on human relations.”

“I create one system that solves every aspect of a shirt at once, making the shirt into a total sculptural form.”

Originally hailing from Canada, Krayenhoff van der Leur grew up in Victoria, British Columbia, an isolated town surrounded by nature. Prompted by the feeling that “there were all sorts of exciting things happening somewhere else, but not where I was,” he moved to Ottawa to study architecture in the 1970’s, realizing that “the closer to a center of culture I was, the happier I was.” He was drawn to architecture because of its possibility to “span the artistic and the scientific,” to push the boundaries of what was possible conceptually, and make it tangible in reality. But the way people dressed, their personal expression of identity through fashion, continued to fascinate him. A formative move to New York in 1998 made the more avant-garde expressions of Krayenhoff van der Leur’s personality through fashion possible in the everyday. “Wherever I had lived before moving to New York,” he says, “I always felt like the weird one, like I didn’t quite fit in, like nobody got me, and I had to sort of hold myself in. When I went to New York, all of a sudden people got me and they got who I was.”

The fashion industry can still be described as a vast economic system, moved by trends, seasons, economics, politics, and labour. To be a fashion designer today is to navigate all those contexts at once. With this in mind, Krayenhoff van der Leur doesn’t see his practice within this structure: “what I do is not fashion, it has no relation to trends,” he says, seeing his work, instead, as a form building exercise, driven by systems thinking and techniques derived from architectural planning. “I have no limits. That means I can take as long as I want to design a pattern, make them extremely elaborate, and take a long time to sew them.” He has developed a flexible design approach, which is applicable to different material contexts. “In any kind of design process, whether it be architecture or clothing, I create a concept in my mind and then use what resources I have at hand to form it—whether it be with textiles, wood-framing, or brick—in order to express those ideas.”

It is clear that studying architecture at a time when modernism was the status quo deeply informed his practice today, which seems to abide by the ethos ‘form follows function,’ initially propagated through the practices of such architects as Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier. For Krayenhoff van der Leur, “what this means is any decorative or aesthetic effect flows naturally from the system of construction and the concept of making.” His approach is functional: “I think of a system to solve a design problem, whether it be the sleeve of a shirt or an interior wall.” A formative architectural project was the construction of Printed Matter, a bookshop run by his husband in New York. The budget was low, but, according to Krayenhoff van der Leur, “The more restrictions you have, the more creative you have to be.” Leaving the construction bare was part of working within those restrictions. “I designed walls that were made of steel studs and then covered them with clear plexiglass. The guts of the building became the interior decoration.”

“The more restrictions you have,

the more creative you have to be.”

If architecture can be described as a system of interlinking aspects, all coming together to create the atmospheres and situations that are lived every day, these garments could be described as small, wearable pieces of architecture. Much like a building, a shirt also has elements that are “useless when separated from each other.” Krayenhoff van der Leur’s pieces are deeply curious objects that challenge the status quo of construction, attempting to rethink centuries old ways of Western pattern making. Some of his shirts, namely Shirt 18A – Splayed, harken back to the 1990’s soft modernism of A-POC, Issey Miyake’s manufacturing method that uses computer technology to create clothing from a single piece of thread in a single process—creating system of clothing from a single length of knit. While the shirts may look rather standard, with a body, sleeves, cuffs and a collar, each one aims to “create one system that solves every aspect of a shirt at once, derived from the shirt as a total sculptural form,” whether it be through considering a shirt as a solid three-dimensional object with his Shirt 15G – Contours or through an organic gathering of textile with Shirt 3A. He maps out the pattern process with the same software used for architectural drawing, the pattern making process producing equally lively drawings. “I start to make elaborate patterns which are not about fluidity of movement, but are re-working the structure of the garment itself.” The shirts final aesthetic is interlinked with how it is built: “I am not trying to make an illusion at all.” Throughout Krayenhoff van der Leur’s work “honesty of expression” is paramount, and he hopes that wearers get pleasure from “the intrinsic idea of the piece. That the most basic problem, how to make a flat piece of cloth three dimensional to fit the body, is solved in a unique way.”

Follow Mark Krayenhoff van der Leur on Instagram for updates on his process. For more of our recent investigations into menswear see our profiles of the designer Don Aretino and the fashion label Goodfight.

Text: Sophie Rzepecky

Photo: Jenny Peñas