While it may be harder to work creatively in a society restricted by censorship, Iranian translator and gallerist Lili Golestan has never taken no for an answer.

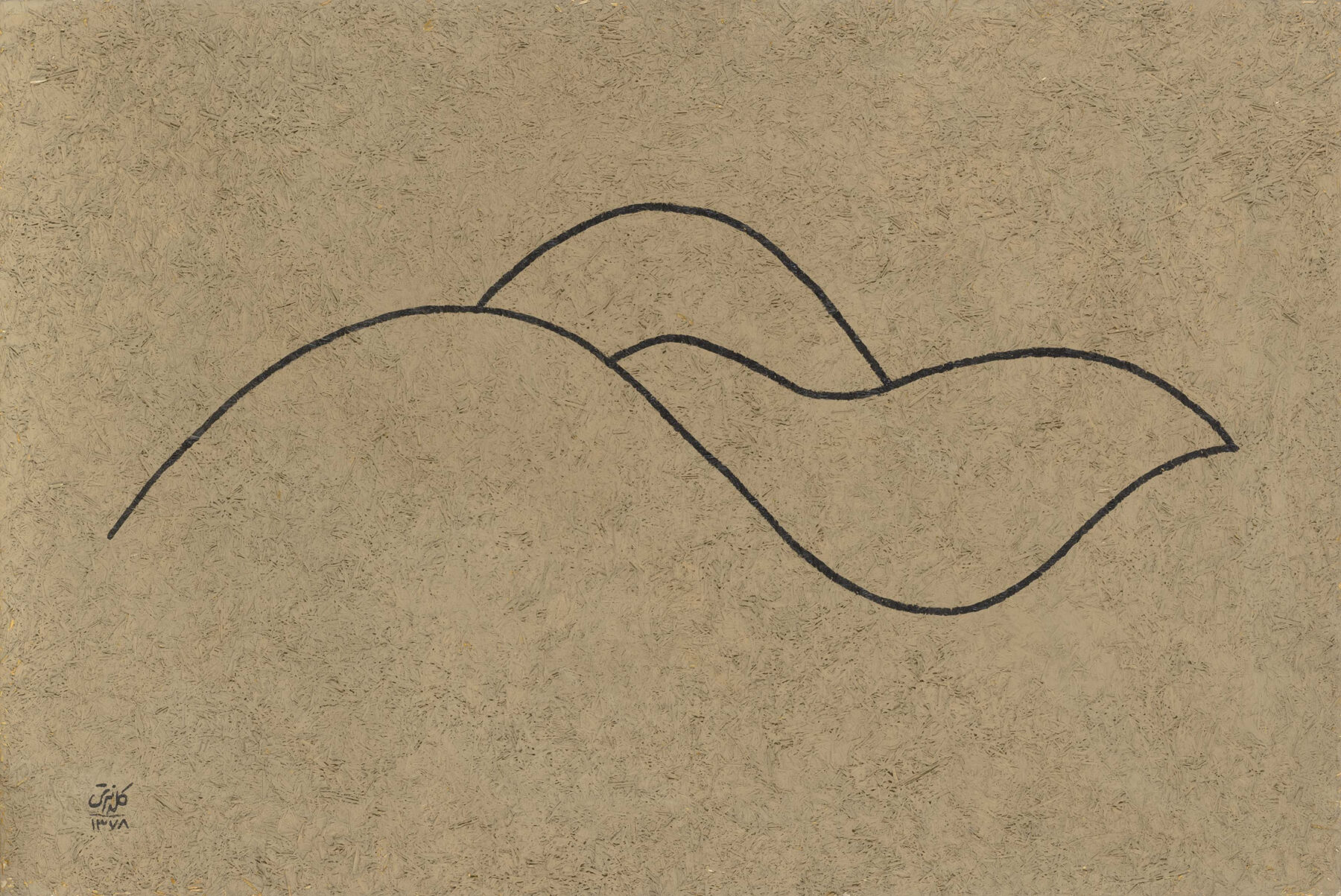

Lili Golestan has prepared black tea and cream puffs for her guests on a rather damp Sunday morning—the kind where the air spits a fine mist that never becomes fully-fledged rain. She tentatively opens the front gates to her residence, revealing a lush, green garden. Sculptural artworks are scattered along the small path leading up to the living space, adjacent to the art gallery that she has run for almost 30 years. Located in Darrous, an affluent suburb in Northern Tehran, Golestan has lived in this three-story house for 40 years. It’s where she raised her three children (she is the mother of Mani Haghighi, the acclaimed Iranian filmmaker) and showcases her most precious belongings: an art collection of about 80 works, which includes works by Iranian contemporary artists Monir Farmanfarmaian and Sohrab Sepehri. Her favorite piece is Red Lines by the painter and sculptor Charles-Hossein Zenderoudi.

Golestan is the owner and artistic director of the Golestan Gallery as well as the translator of 34 books, and undoubtedly one of the most influential characters in Tehran’s contemporary art scene. Straight to the point, she’s is nothing if not frank: “I always say what I think.” Her wardrobe is also impeccable: velvet pants, a bourbon-colored blouse, matching jewelry, and black pumps. Her hair is perfectly coiffed. “I know you don’t see it, but I’m 74-years-old this year,” she says, grinning.

“I’m not very nostalgic. The past is the past and it’s finished. I’m going to move forward. I will stay and I will work.”

Golestan was born into one of Tehran’s most notable families; her father was Ebrahim Golestan, a writer and filmmaker whose career spanned over half a century. Her brother, Kaveh Golestan, who was killed by a landmine in 2003, was a renowned photojournalist, best-known for his coverage of the Iranian Revolution and the Iran-Iraq War. She describes her family as artsy and remembers growing up surrounded by painters and intellectuals. Golestan herself spent some of her formative years in Paris studying textile design before moving back to Tehran, landing her first job in TV as a costume and stage designer. “That was the best time of my life, we had so much fun,” she recalls. She left the job to care for her first child but resented the idea of having to stay home, and it wasn’t long until she was searching for her next creative project.

Thanks to her first translation of Nothing, and So Be It—a seminal first-hand account on the Vietnam War by the Italian journalist Oriana Fallaci—Golestan became famous overnight. Although it put her under a lot of pressure (“I felt a responsibility to do it right”), it also gave her the opportunity to break away from her father—a man she describes as bad-tempered, dominant, and unreasonable—and see “that I am myself and that I have to take care of it. I have to respect myself and move with caution.” She also overcame a stutter she had suffered from since her childhood.

Golestan has translated from French to Farsi, sometimes from Italian, at times from Spanish—she has even translated from Greek—and has tackled novels, biographies, and poetry. Six months ago, her translation of Romain Gary’s 1975 novel The Life Before Us hit the stands and has been republished eight times in one month. It took Golestan 12 years to fight for its release. Did the government reject a piece about a young Muslim orphan because the book deals with prostitution? “No,” Golestan explains. “[It was] because he’s not very intellectual, nor polite. They told me to make him sound polite. I said: ‘How? I can’t censor him myself. I’m not allowed to change the character of this little boy.’” Golestan is as deliberate and idiosyncratic as her startling, relentless quest to fight for artistic freedom in her home country, however uncomfortable that might be; she’s had to fight for each of her translations and five are currently banned from being republished.

The Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance—or, as Golestan calls it, “the ministry without any culture”—is located in an imposing building in downtown Tehran. Close to some of the city’s most professional, privately-run galleries and the Iranian Artist Forum, the institution’s title, written in bold letters across the concrete building is unmissable. In Iran, the ministry determines whether creative initiatives can be pursued or not, what title they can own (they have to be in Farsi) and whether they are able to include or be hosted in public spaces or not. Golestan is not an unfamiliar face here. “I have argued with the ministers a lot, but I’ve won every time. Because I have rights. It was very hard to speak to them, they couldn’t understand me. I couldn’t understand them, either. Like seeing two people from two different worlds. I would spend days arguing about just one phrase. My energy was gone. It’s very hard, but I must do it,” she says. Does she just walk into the ministry, one that has forced numerous local businesses to cease operations, and make her case over a cup of tea? “Yes, just like that, without any fear. Why should I be afraid? I am more intellectual, smarter, and more knowledgeable [than them]. They must learn from us,” she says, laughing. Was the fact that she is a woman ever an obstacle? “No, not at all,” she responds. Her gallery also had her cross paths with the ministry, although, according to Golestan, literature was—and is—a much bigger deal to them. Her instinct and willpower, paired with a singular competence in recognizing and promoting local, emerging talent has led her to become an integral, almost indelible figure in Iran’s cultural scene for the past four decades.

“Why should I be afraid? I am more intellectual, smarter, and more knowledgeable [than The Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance].”

At the age of 30, while maintaining her translation career, caring for three children, and managing a household, Golestan separated from her husband, cinematographer Nemat Haghighi. “I realized that while I was doing all that, he was living independently with no boundaries, no responsibilities,” she says. However difficult the split was for Golestan, it felt right. “Those days were the hardest of my life because I didn’t have a job. I was a 30-year-old woman with all of her dreams and wishes but with no money.” The income from the books wasn’t sufficient, but what she did have was a house with a spare garage, built by her father, that she turned into a bookstore, before relaunching the space as her gallery in 1988. Despite the tumultuous period (the Iran-Iraq war lasted from 1980 to 1988)—“everyone told me that it was not the time to do it”—her gut feeling and openness to taking risks proved her right. The vernissage attracted throngs of people, as well as police officers who, when they learned that poet and painter Sohrab Sepehri’s works were on show, laughed and left. Golestan was flabbergasted. “Until I remembered that his poems were read all over the national television and radio shows,” she says. “They liked him!” First, Golestan built the gallery with her father’s collection but soon turned it into a platform for unknown talent—something she still does to this day.

Lili Golestan’s Private Collection

Iran-based gallerists are required to seek permission for every single work they exhibit, something Golestan is unwilling to accept. Ten years ago, she therefore approached the ministry to announce she wouldn’t ask for the go-ahead anymore. To her surprise, they didn’t close down the gallery. Instead, she encouraged fellow owners to follow suit—Tehran is home to about 200 independent galleries—and most of them did. “It was like a new rule,” she recalls. “We must have the courage to fight the ministry, the things they do aren’t fair or good.”

Was she ever afraid of anything? “The war; the bombings,” she responds, raising her head to the sky above her terrace. But she always remained fiercely loyal to her home country, including the obstacles and advantages that living here brings. “We’re staying to keep everything in our hands; we’re not going anywhere,” she says, referring to those who stayed in Iran after the revolution. Golestan initially supported the revolution and its successful efforts to overthrow the country’s monarchy and the ouster of Iran’s king, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Her support didn’t last with the death of supreme leader Ayatollah Khomeini, following which “the country went the wrong way,” due to corruption. Nostalgia is not her thing, though. “The past is the past and it’s finished. I’m going to move forward. I will stay and I will work,” she says. And she is busy: Golestan Gallery is booked up until 2021, with one new exhibition opening every Friday, all featuring Iranian artists. “It’s a very strange country, with very strange people. Unpredictable, but very lovely. Challenges are interesting to me. When I go out of Iran, I get bored.”

Lili Golestan is the owner and artistic director of Golestan Gallery based in Northern Tehran. For almost 30 years, the space has exhibited up-and-coming Iranian artists whose works span painting, photography, and sculpture. Golestan is also renowned for her literary work, having translated 34 books into Farsi.

Text: Ann-Christin Schubert

Photography: Negar Yaghmaian