Over the last three decades, the lead singer of German avant-garde outfit Die Goldenen Zitronen has evolved from a punk provocateur into a sought after theater director and arguably one of the most important left wing intellectuals in Germany.

In the Volksbühne canteen, Schorsch Kamerun is enjoying a lunch of braised cucumbers, minced meat, and potatoes. Wearing flip-flops, a polo shirt, and a welcoming smile, the director looks cool and collected despite being in the midst of rehearsals. The piece we’re here to talk about is his requiem for the Bauhaus, a sprawling musical theater production and multimedia installation that will stretch over several areas of the Volksbühne, including the main stage, the Grüner Salon, and the Sternfoyer. There are more than fifty people involved in the project and, accordingly, the organization and logistical efforts are immense. Is he feeling stressed? “No… but, of course, there is some pressure to get things right.”

“In the 1990s, the Volksbühne kind of invented it for theaters to be open to different forms of programming.”

Working at the intersection of the arts, music, and theater, as well as directing the occasional radio play and running Hamburg’s infamous Golden Pudel Club, Kamerun is arguably one of the most important left-leaning intellectuals in the German-speaking world. Born 1963 in Timmendorfer Strand, a community of roughly 8,900 people in the northernmost German state Schleswig Holstein, Kamerun moved to Hamburg in the early 1980s. In his semi fictional autobiography Die Jugend ist die schönste Zeit des Lebens (Youth is the most beautiful time of life) he sums up his coming of age in Timmendorfer Strand as follows: “the futility of those days was unbearable.”

When Kamerum arrived in Hamburg, the city couldn’t be more different than the sleepy town he grew up in. It was in the midst of a countercultural rebellion, with squatted buildings in the neighbourhoods of Hafenstraße and St. Pauli becoming beacons of resistance against state authority. Unsurprisingly, this setting was a breeding ground for punk bands such as the one Kamerun co-founded in 1984—Die Goldenen Zitronen. Starting out as a fun punk outfit with a serious edge, the band provided critical commentary on society from the very beginning, and, to this day, continue to question our current political and economic frameworks. In 2004, Kamerun put on one of his first theater pieces, The Golden Age Of Punk And Working, and has since directed plays based on the works of authors like the Norwegian writer and artist Matias Faldbakken. Most recently, he reenacted the ongoing gentrification of a former working class neighborhood in Nordstadt Phantasien (Nordstadt Phantasies) at the Ruhrtriennale 2018. For Kamerun, this progression is “intuitive. As long as I can express myself, a topic works for me. Whether it’s the Pudel Club, music or theater. All this comes from a very important motivation of me wanting to interfere, to irritate.”

“Everything that is radical will end up in mainstream.”

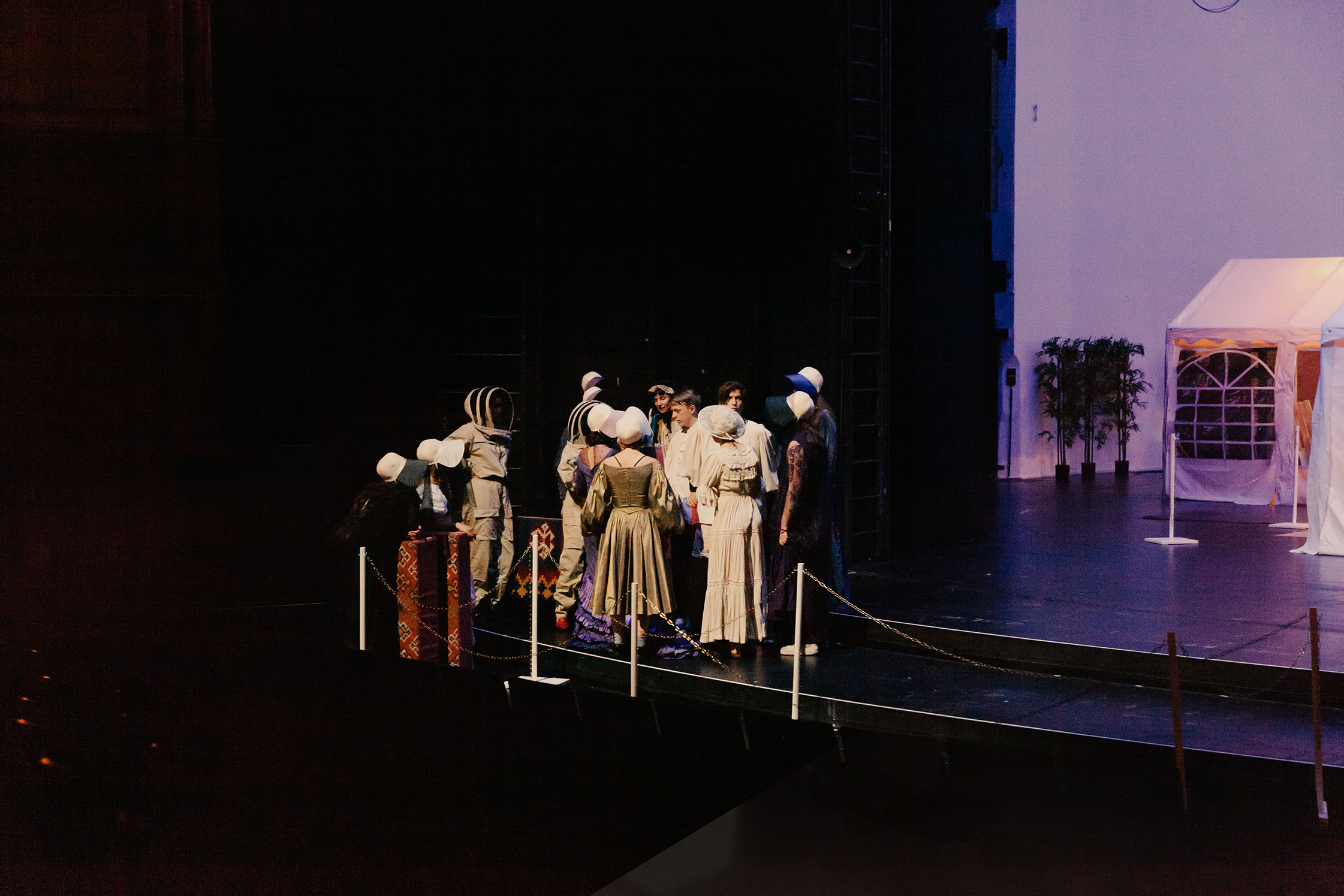

The initial concept for his current project came out of projekt bauhaus, a consortium that’s managing and hosting events around the design school’s 100 year anniversary. “They approached the people at Volksbühne and they thought it might be a good idea to ask me,” explains Kamerun. Initially, he felt “afraid” of the celebratory tone of the centennial and wanted to examine how much, if any, of the initial spirit of the Bauhaus still existed today. “I wondered why I should join this party at all. So, we came up with the idea that we should bury the Bauhaus to really free it. The idea was born to call it a requiem.” Accordingly, the piece is to be understood like a playful burial ceremony for the Bauhaus and will comprise a party, a series of performances, musical installations, and interventions. On the main stage, they’ve installed a camp made of tents. Der Grüne Salon, one of the Volksbühne’s side stages, has been turned into a sports studio for abstract dance, with the space outfitted with an arrangement of levers and covered by transparent awning in blue, red and yellow, the colors of Bauhaus. The Sternfoyer of Volksbühne was turned into a performance space for live music, which will include an opera singer and a musical performance by Kamerun himself.

When it comes to his artistic practice, Kamerun diagnoses himself as an “immaterial artist.” To put it simply, he’s about the ideas. Accordingly, his show at Voksbühne will not be about Bauhaus design or architecture but will focus instead on the kind of mindset and historical moment that materialized when the movement was founded in Weimar in 1919. Europe was shattered after World War I, and it was necessary, according to Kamerun, “to see how to go on as a society in a more loose and non-militaristic way of living together. The modernists were an avantgarde who really were ahead of the game in thinking about how to design society and how to rethink the future.”

For many people, Bauhaus is about chair design and architecture but for Kamerun, the immaterial artist, it’s also about the radical core that lies within some of its utopian ideas. In their time, they were new, fresh and even radical. Yet, Kamerun knows that “everything that is radical will eventually end up in mainstream. There are cakes with the motive of die Rote Flora in Hamburg on them, you know,” he says of the long-standing left-wing cultural center and squat right in the middle of Hamburg’s gentrified Schanzenviertel, “nihilism and irritation can and will become brands. One of the founders of punk, Michael McLaren was a situationist and he knew that. He knew that we live in a society of spectacles,” Kamerun says.

He knows that he is part of the spectacle and he’s not denying it. On the contrary. Throughout his career he developed a keen eye for which projects to choose and how to navigate the cultural sector. He’s very interested in processes of subjectivation, in how people manage their own self under economic pressures. “I’m critical towards this [attitude] but I’m also aware of the ambivalences. Moreover, I’m in the business of contradictions. I’m a brand with parameters that you can pigeonhole,” he explains, referring to what he sees as a shift in how brands and individuals market themselves: “Capitalism reinvented itself. Today, even a cobbler knows what framing is and would call his shop after the quarter he works in.”

Kamerun recognizes that culture and economics are always entwined; when he and the co-owners took over the building at Golden Pudel Club in 1994, nobody wanted it—now that area of Hamburg is seen as one of the most desirable areas to live. He’s very aware that, with his practice, he’s also part of the spearhead that drove gentrification in this area. Nevertheless, Kamerun is also working to counteract these tendencies, or at least to try to keep the momentum of irritation alive and kicking. That is why they in the past they’ve changed the club’s name occasionally, to Dr. Helmut Kohl, for example, the former conservative chancellor of Germany—not the most obvious choice for a space that considers itself leftfield and diverse. But, as Kamerun himself admits: “Contradiction is a brand.”

To delve into the stories and subjects behind his work, Schorsch Kamerun often chooses the path of a wide collaboration. His core team consists of his partner and set designer Katja Eichbaum, costume designer Gloria Brillowska and Berlin-based producer and musician PC Nackt. The Volksbühne cast featured in this production were: Paul Herwig, Paula Kober, Anne Tismer, Corinna Scheurle, Mia von Matt, and Frank Willens.

For Das Bauhaus—Ein rettendes Requiem, Kamerun collaborated with P14, a young performing group from the Volksbühne, an acting class from the University of the Arts in Berlin (UdK), as well as theater collective DIE ETAGE. The show premiered on June 20th.

Text: Fabian Ebeling

Photography: Aimee Shirley