In the 21st century, cities are facing a crisis. On one hand, they’re more desirable than ever: Young people are flooding back to urban areas and start-up offices are bringing dynamic industries back to forgotten neighborhoods.

On the other, gentrification is raising real estate prices beyond the reach of many with urban space increasingly occupied by luxury development projects not to mention national economies are still recovering from the recession. On the front lines of climate change, cities put immense pressure the environment as well.

Architecture and design are inextricably involved in this condition. Our built environments shape how we live on a daily basis so shouldn’t those in this field be the first to adapt? Ilias Papageorgiou, the young Greek architect and partner at the award-winning New York architecture firm SO – IL believes architects have been slow in responding to the new state of cities. Confronting the need for sustainable, flexible urban development, MINI Living worked in collaboration with SO – IL to design Breathe, a pop-up residential building in Milan that represents one possible method to confront these urban issues.

Nestled among Milan’s bustling alleys, Breathe appears like an apparition that looks like it came from nowhere, and might suddenly disappear as well.

“One of the biggest urban challenges is how we can change architectural and urban design from a rather passive condition into an active ecosystem.”

MINI Living is an ongoing initiative for the company that leverages the same “creative use of space” in their cars as it does for domestic spaces as well by working to develop solutions to housing problems. In 2016, MINI launched Do Disturb, a 30-square-meter apartment that featured dynamic walls able to format the space in multiple configurations. The home becomes a “micro-neighborhood”, with specific customizable areas devoted to socializing or privacy, work or play. It’s all about matching the pared-down lifestyle of modern city dwellers with a new kind of efficient space.

Breathe, too, is about efficiency and mobility. The push toward city centers “creates some challenges, such as highly densified urban conditions lacking human scale and disconnecting us from our natural surroundings,” says Oke Hauser, Creative Lead at MINI Living. “One of the biggest urban challenges is how we can change architectural and urban design from a rather passive condition into an active ecosystem,” he adds. This is where MINI’s collaboration with SO – IL’s comes into play.

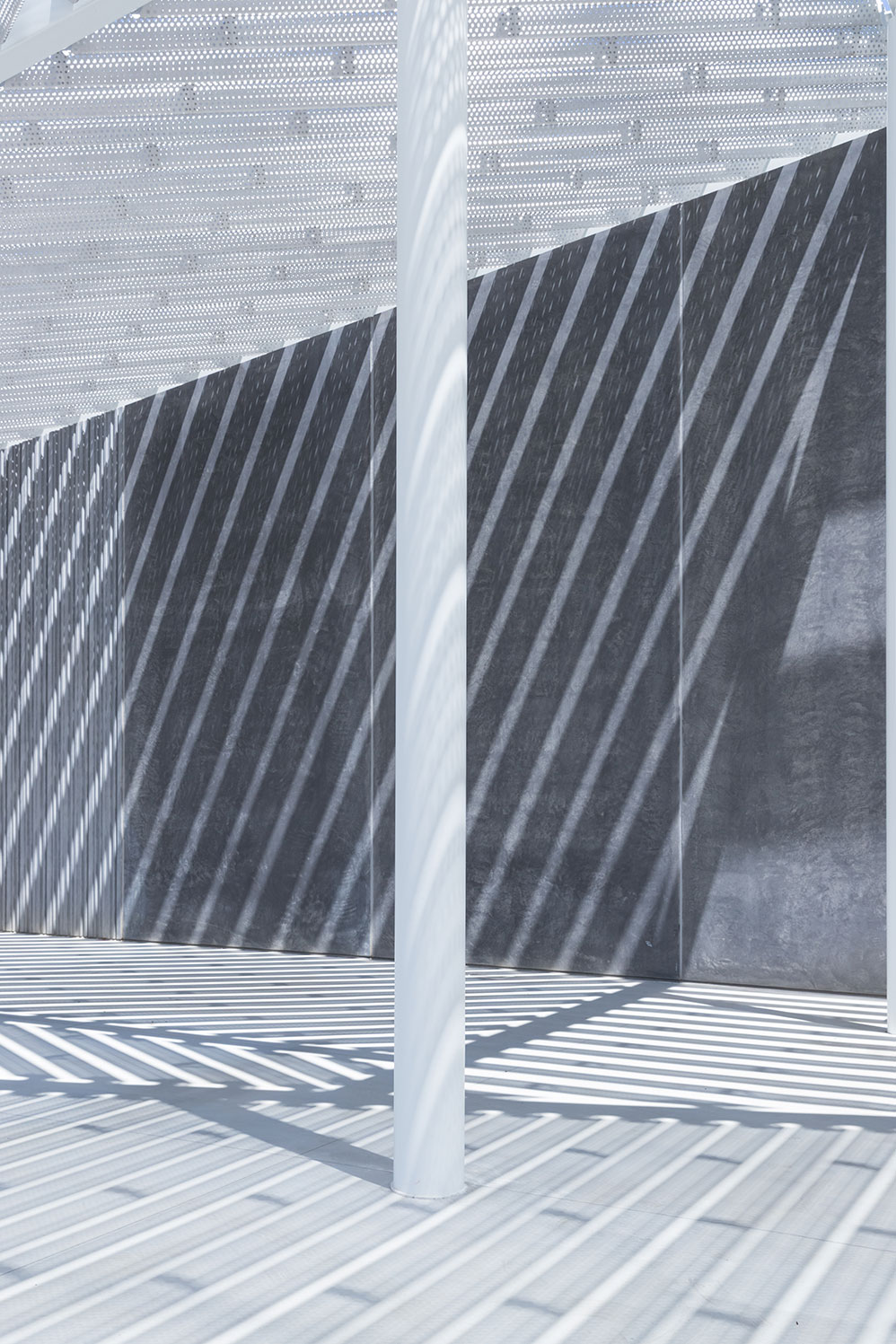

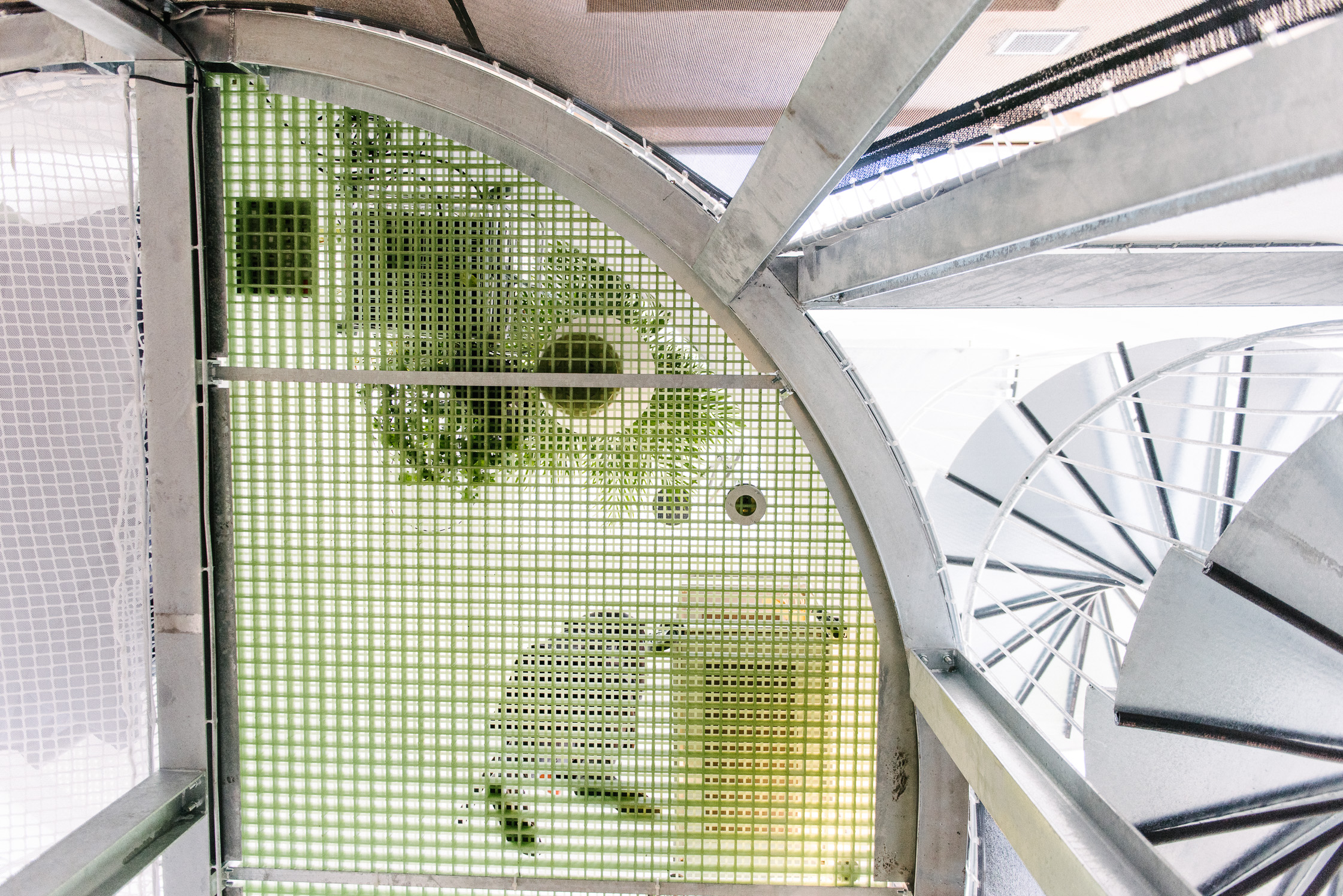

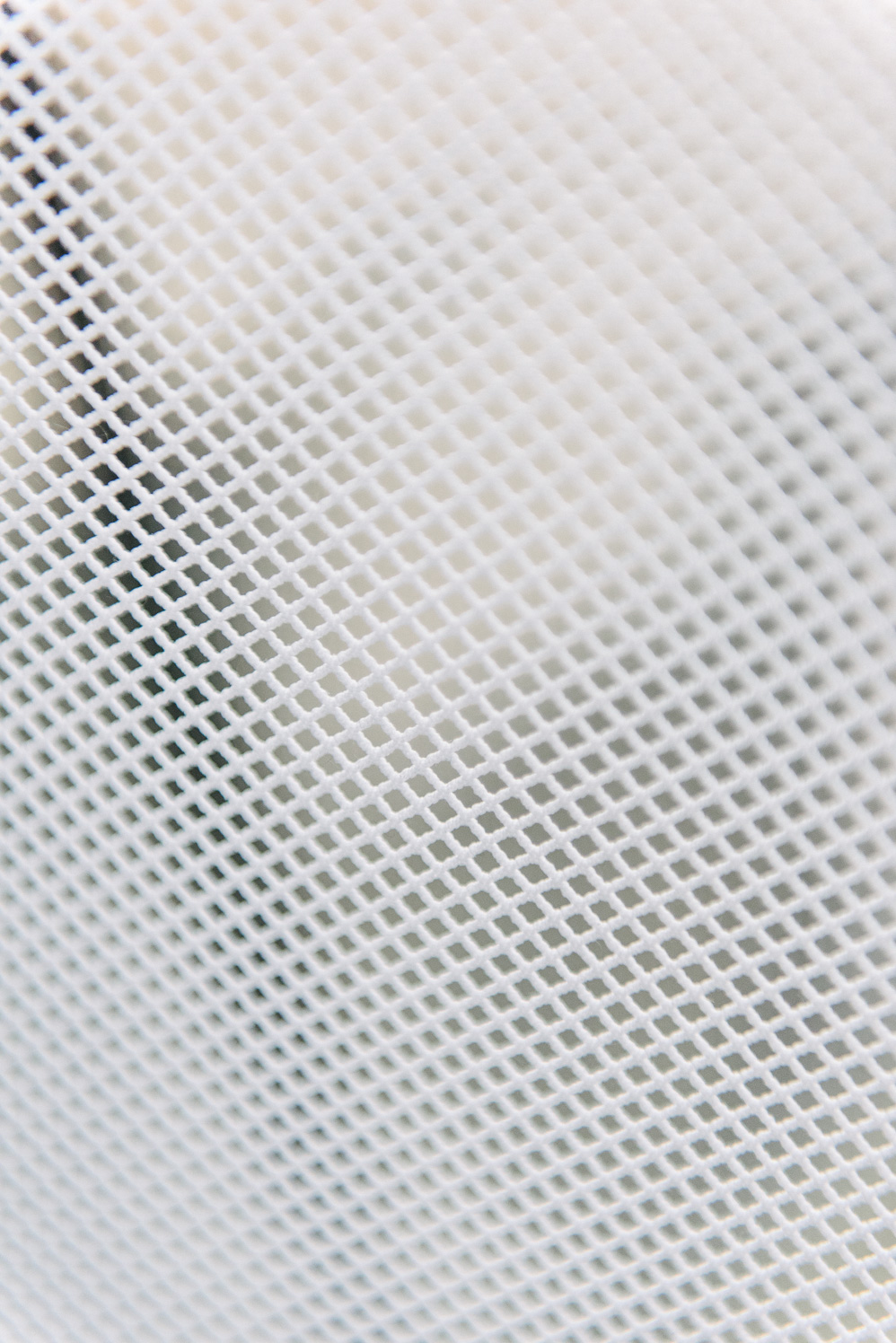

Constructed of a semi-transparent mesh fabric stretched over a metal armature and installed in a Milan alley for the Salone del Mobile 2017, the Breathe building might be described as something of a “ghost,” as Ilias puts it: an apparition that looks like it appeared from nowhere, and might suddenly disappear as well. It’s fleeting in purpose as well as construction, alighting in a pocket of unused space in the warp and weave of the bustling Italian city.

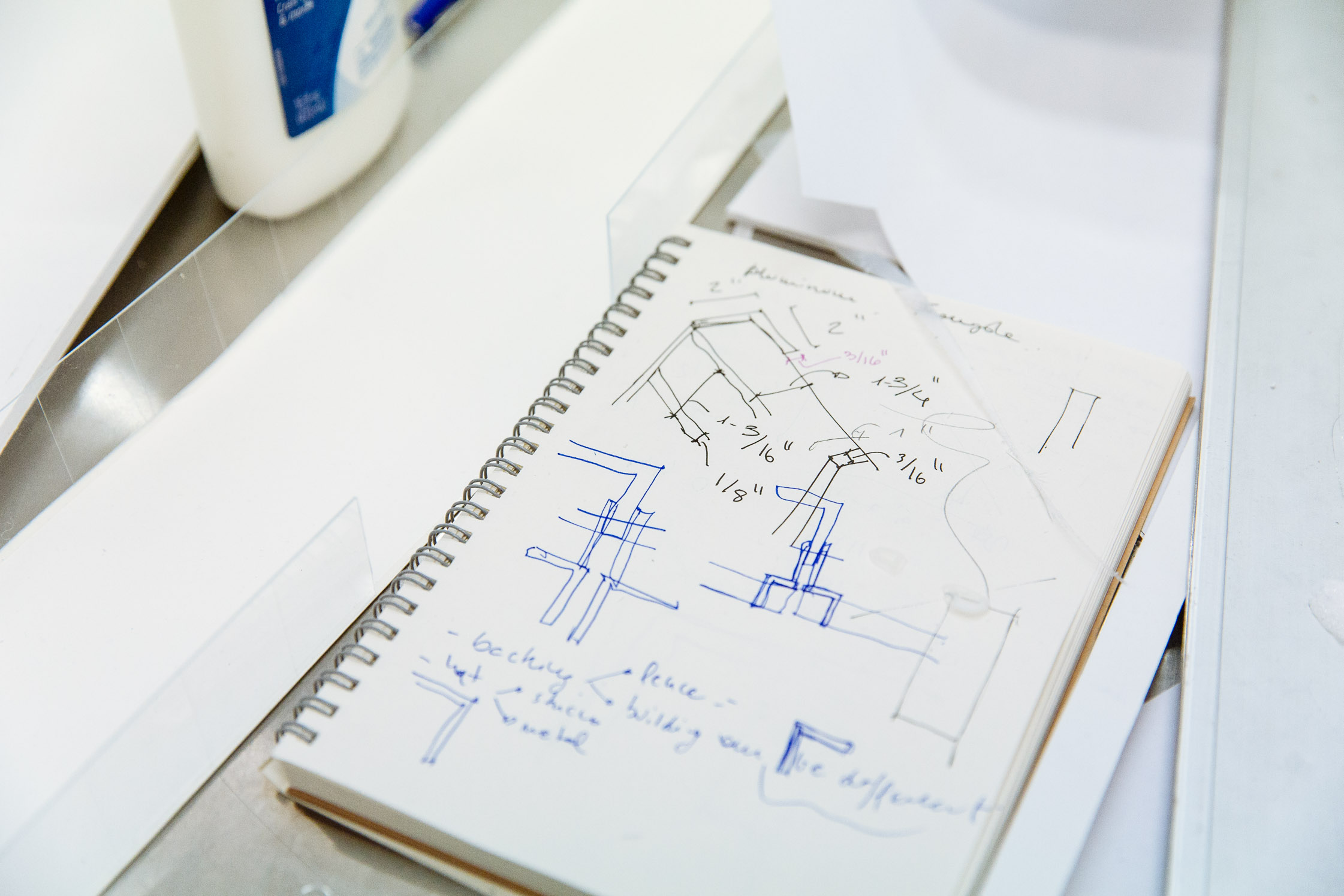

Across the Atlantic, the SO – IL office is a second-floor space in Downtown Brooklyn that used to be a beauty salon, as many of the buildings on the street were. But SO – IL has renovated it into a blank canvas, with pristine white walls, wide windows, glassed-in conference rooms, and a station for sculpting models out of foam board. One such model now completed and on display is of Breathe house. Crafted to look like the skeleton of a building, with an ovular stack and an angular aperture at the bottom so pedestrians can cross underneath it at the end of the skinny Milan alleyway. Its name comes from its ethereal nature as well as the function of the fabric that stretches over its framework. The rubbery Japanese material, which has networks of holes the size of pinheads, actively filters the air around it, removing pollutants. “It’s self cleaning,” Ilias says. As the material heats up, “the sun decomposes dirt and other elements.”

“Sustainability is not just a thing; it’s more a process, something that there’s no end to,” he continues. “Sometimes I think people or architects approach the issue as if it’s a final solution or result.” MINI Living’s Oke Hauser reinforces the notion of process: “We’ve created a house as an active ecosystem that makes a positive contribution to its environment.”

But the transparency of the dwelling as a whole affords another role. “What can you do as an architect that is trying to help people to become more aware of their surroundings and the environment around them,” Ilias says. Air and light flow throughout Breathe, so the entirety of the space is illuminated. Walls don’t really exist; rather, the interior rooms are ambiguous and you’ll always know where the other residents are as they cast shadows on the walls, almost like a traditional Japanese Shōji screen. “We wanted the translucency so we could achieve this connection between people,” the architect continues. “You would sense different sounds and silhouettes of other people moving.”

“The ultimate goal is to cultivate an ethos of caring.”

The ultimate goal, Ilias believes, is to “cultivate an ethos of caring.” The building connects people to people and their surroundings. Yet Breathe is not a traditional family dwelling. Rather, it’s in the vein of co-living arrangements like those created by companies such as WeWork and Roam. Just as the traditional definition of the family has evolved into manifold networks of friends, partners, and colleagues, Breathe is also flexible, able to house a nuclear family or a small communal group. There are three living spaces arranged on top of each other to one side of the segmented structure, a more open shared atrium to the side, and then on the ground floor space, a kitchen and living room. On the roof is a planted terrace that collects water for the house.

Breathe is meant to house the kind of digital nomads that so many people identify as these days. Whether entrepreneurs, artists, DJs, or consultants, jobs and careers are much less fixed than they used to be. Fittingly, Breathe can also adapt to wherever it finds itself. “You move it to a very cold climate, like Siberia, you would put some skin that would create some insulation. Or in New York, maybe we’d need something for sound and acoustics,” Ilias adds as a particularly loud jackhammer runs on the street outside the office.

At the SO – IL offices

The firm has engaged with this idea of flexibility throughout its past decade of history. SO – IL was founded by Florian Idenburg and Jing Liu in 2008 (the two architects are a couple who married in 2006). Ilias was with the firm since its inception; he met Florian while he was a student at Harvard and Florian was working for the Japanese firm Sanaa. SO – IL’s early days were made more difficult by the financial crisis.

Yet the challenge of surviving also helped the firm become what it is today. “We were so small, we could not go smaller,” he says. “Maybe that also allowed us to not start working with huge or commercial projects but more trying to find out, how will we approach architecture?”

“Everything has become untethered. We bounce about, footloose, on a network of intersections and knots.”

The project that made SO – IL’s reputation was an installation called Pole Dance at the Museum of Modern Art PS1 in 2010. The architects won the museum’s Young Architects Program commission series and installed a series of poles in the courtyard that held up netting with beach balls rolling on top. The mesh stretched to encompass hammocks and pools, turning the space into a dynamic party sometimes activated by actual pole dancers, spinning on the structural poles.

This dynamism was reflective of a greater global condition: “Everything has become untethered. We bounce about, footloose, on a network of intersections and knots,” the architects explained in their manifesto for the project. The iconic project instantly drew new clients to the firm even as it established a basic vocabulary for the rest of their work, that stretches to the Breathe house.

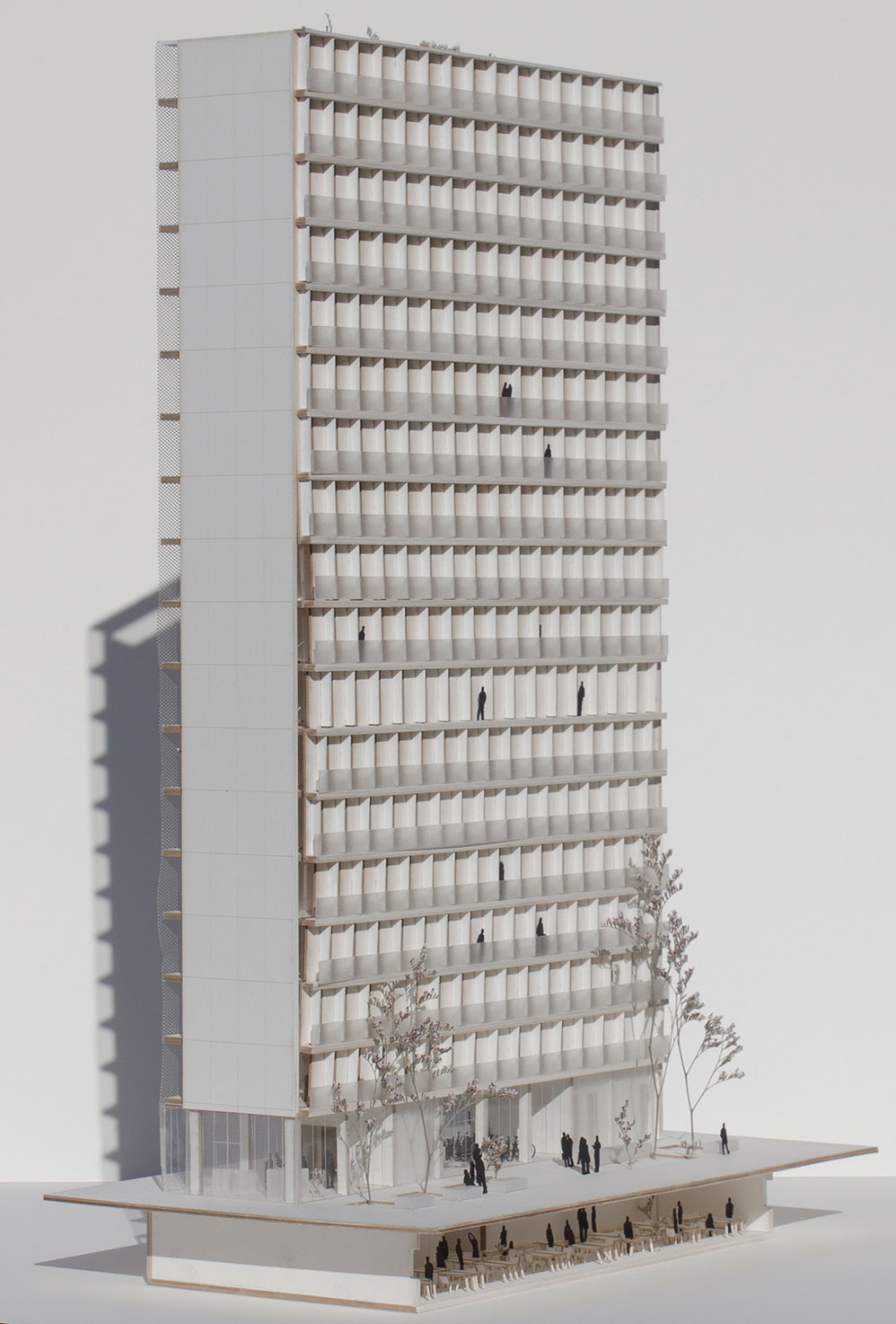

Another model in the SO – IL office is best described as a skinny tower with a patterned facade shot through with large windows. It’s a residential development for Kips Bay in Manhattan that’s meant to test the concept of micro-apartments, individual studio units that contain just enough space for one or two people to live comfortably. The entire building is composed around the needs of individuals rather than families, making it much more dense than the average development. But efficiency doesn’t mean discomfort. “It’s such a thin building so every single apartment has cross ventilation and lighting and exterior space,” the architect says. “They go all the way through.” There’s also a shared office space on the ground floor.

Further north in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Greenpoint is A/D/O, MINI’s experimental creative space designed by nARCHITECTS. The space is seamless and open, transitioning from bookstore to gallery space to coworking office and restaurant, with floor-to-ceiling windows looking out onto the industrial street.

A/D/O is also a part of MINI Living, a way to find new spatial solutions for crowded cities and urban residents in need of flexibility. “We offer studio spaces as well as rigorous programming around current issues through our in-house design academy,” Oke Hauser says. “We are also inviting the public to join: the building was conceived for designers yet is open to all.”

“In our generation, this idea of permanence—that I go to a place and this is where I make my life and stay there forever—is over.”

Over coffee in the sunlit A/D/O cafe, Ilias discusses the lifestyle changes that he sees architecture reacting to, and shaping in turn. Buildings are a slow medium to respond to realities on the ground. “Technology is very good, but it evolves at a much faster pace than architecture,” he says. “We’re not going to change the economy or how things are ordered in society through architecture, but we can maybe define the spaces where these things will take place,” he adds.

“In our generation, this idea of permanence—that I go to a place and this is where I make my life and stay there forever—is over,” the architect says. “It’s nice because you’re able to experience more places in the world, but maybe for us it’s also limiting. We can’t buy property and we’re more precarious.” New typologies of buildings, as designed by SO – IL, will help us cope with the city landscapes changing around us. “I think we can find solutions that can also offer a very good quality of space and experience.”

Le Corbusier defined the house as a “machine for living.” Looking back, Ilias sees it as more like an interface between humans and machines: the appliances, kitchen, and laundry, each a mechanism for converting resources into a domestic life. But now, with food delivery start-ups and Airbnb and coworking spaces and Uber, we don’t need as many machines in our home. That means redefining the home as well.

“It’s nice to cook, but you get everything with the swipe of your finger, so maybe that opens up an opportunity. We can make an amazing environment that doesn’t need all these elements,” he says. “It’s all about experience and place and pleasure.”

FvF and MINI have teamed up to investigate ideas for future urban living through stories from our network as well as by accompanying MINI Living’s international collaborations with architects and designers. To learn more about the work of MINI Living, read the interview with Oke Hauser on FvF or visit MINI Living’s website.