A cool morning in Bagru, a man with blue hands opens a gate to the village compound. Behind the chipped grey steel lies a world of color — not just the dry gold dust and impossibly azure skies of Rajasthan, but fields that shimmer with pink and indigo.

A house to the left, draped in fluttering skeins of butter yellow. A cow with purple ears ambles past, and you catch yourself wondering if Bagru is where rainbows come when they need a coat of fresh paint. Humming to himself on the way home from a temple, Vijendra Chhipa beams as he spots visitors. Seven years ago, another visitor, on a morning just like this, had changed the fate of his village forever.

The Chhipas, a caste settled in Bagru, but also found in other parts of Rajasthan, Gujarat and Nepal, have traditionally worked as cloth dyers and printers for generations, an occupation with a somewhat violent origin in Hindu mythology. According to the story, when the entire Kshatriya (warrior) caste was facing genocide at the hands of a vengeful lord called Parashuram, one pair of Kshatriya brothers hid themselves in the temple of a goddess. Sympathetic to their mortal plight, she offered them a chance at redemption by handing one a needle and thread, and the other, the leaf of a red betel plant to make pigment with. Since castes in India were believed to be mainly occupational – even though they are reinforced in both social practice and discrimination until today – it was thus that some warriors were transformed into a caste of “dyers”, or those who make colors with natural pigments, and tailors.

This portrait has been produced in collaboration with BMZ.

Vijendra Chhipa’s earliest memory is of sitting under a four-by-four foot wide wooden table, at his father’s feet, hand block printing on discarded scraps of cloth, a far cry from his own well-lit, airy and spacious studio, which is lined with vast, endless tables, walls covered with shelves that hold blocks of every style and vintage. Born to the fourth generation of a family of dyers and printers, Vijendra always loved fabric and color — but like millions of Indians, he had hoped that a college degree would allow him to break away from tradition and choose his own profession, instead of the other way around. When he was a young boy, Vijendra recalls , printing and dyeing wasn’t much of an industry anyway.

“We printed fabric to barter for provisions, for instance we’d give some cloth to a farmer in exchange for wheat. My father printed about 35 to 40 metres of cloth every week, and we’d sell that at the local fair every week” he says. Studying hard to fulfill his dream of becoming an air force pilot, Vijendra continued to read about the world of textiles, blocks and pigments in his free time, wishing that he could share some of his new knowledge with the generations of printers and dyers that lived around his home in Bagru.

“…To delve deeper into the craft, understand where the materials came from, how they were made, why they were made in a particular way… this was very important to me. The people of Bagru, who are traditional printers, only knew how to do their work, with no idea of how, what or why they were doing certain things. They weren’t able to communicate the fact that they were using a process that was over three or four hundred years old, they didn’t understand that this was something that adds value to a finished product,” he mused.

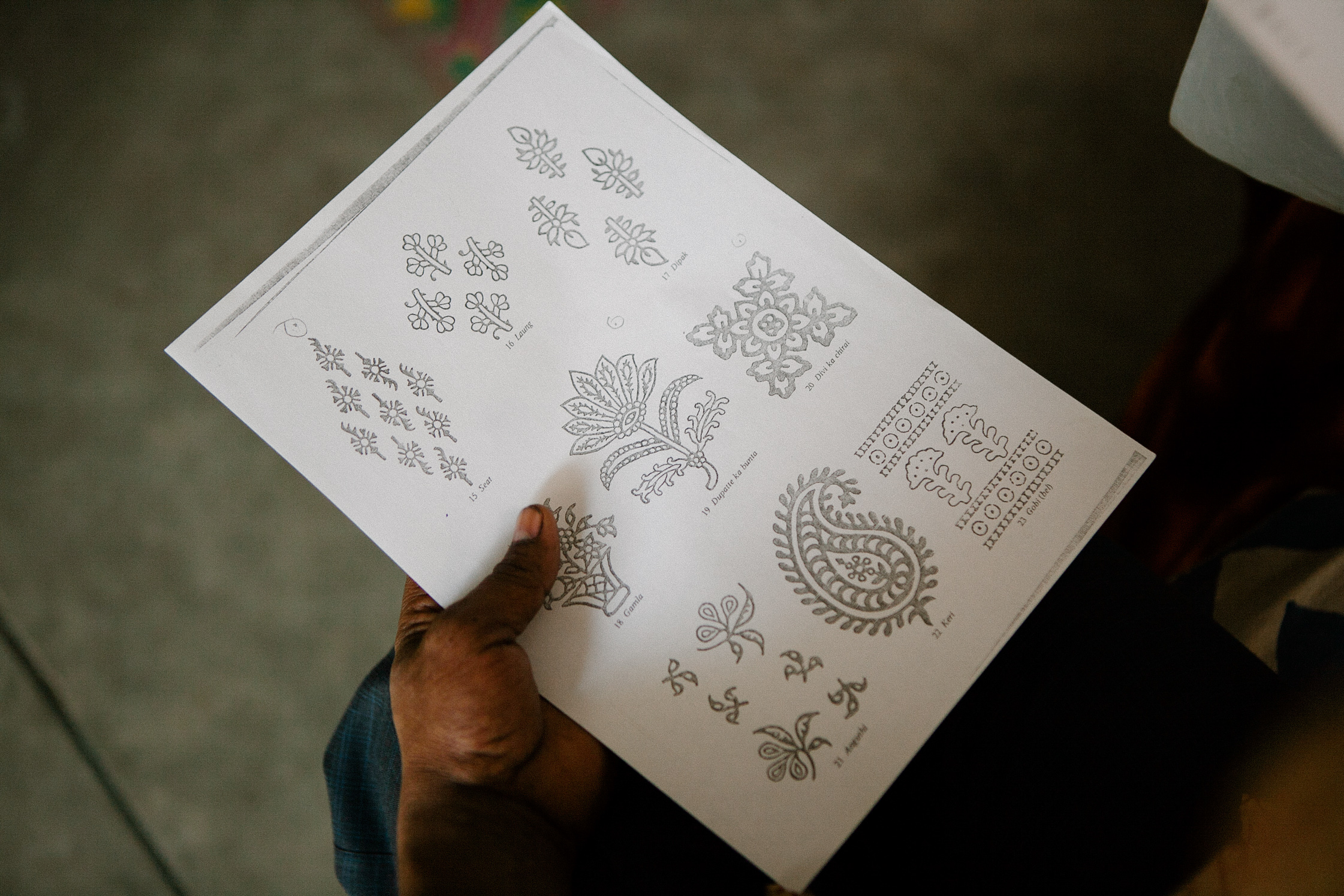

It was only during this time that Vijendra truly began to understand the wisdom of the traditional way – hand block printing with vegetable and mineral dyes produced less cloth than the machines that were swarming the market, but at far lesser cost to the environment. The vivid blues came from Indigofera tinctoria, the lush pinks, reds and oranges from begar, alum turned prints grey, and the longer one fermented syahi, the deeper a dyer’s blacks would become, darker than a starless night. Before dyeing, fabric had to be soaked in harda or a natural mordant, to bind color to the natural fabric.

In the extreme climate of Rajasthan – where summer months can be as hot as 49 degrees Celsius and winter nights as cold as 2 degrees – land and water were essential to survival. Vijendra realized that a traditional home-based unit, like the one that generations of his family had used, meant that one needn’t spend money on vast tracts of land to set up factories. Further, since the dyes were mostly derived from natural plant and mineral dyestuff, the water used to make and wash them could be re-used to irrigate crops. As he learned more and more, young Vijendra became consumed with telling the story of the Chhipas and the tradition of hand block printing.

Telling the story was becoming easier for other reasons too. Moonlighting as a hotel receptionist when he wasn’t at school, Vijendra was rapidly becoming the proficient in English. Entrepreneurial in spirit and determined to share the craft and history of hand block printing, Vijendra was soon trying out new words and phrases on the hotel’s meagre clientele of college students and businessmen. Today, Vijendra’s own children, Chehika and Yash, speak in the fast-paced, emotive English of their favorite movie stars. Smiling proudly at their sassy repartee with his foreign visitors, Vijendra’s eyes mist over when asked if he expects them to join the family profession someday, “That depends on what their dreams are,” he says.

A twist of fate, devised by a mischievous goddess that favored the Chhipas of Bagru, or the Indian Air Force – depending on one’s beliefs – had destroyed Vijendra’s dreams of becoming a pilot, by rendering him ineligible to take the exam. Defeated, but not broken, he began to sell insurance to earn money, and was doing reasonably well for himself, when his father passed away in 2007, leaving the small dyeing and printing business to Vijendra and his five siblings. Two of his sisters were married into families that had their own businesses, one of his his brothers was a local political representative, and the other had a screen printing business outside Bagru — which left Vijendra as the only party interested in hand block printing natural cloth.

Even though he was now running the ship, Vijendra was not satisfied with running a small, isolated operation like the other dyer-printers of Bagru. He was constantly looking for ways to apply his education and contacts to improving the lives of the Chhipa community. He would write to various ministries to enable artisans to take bank loans and extend their businesses. He lobbied with local representatives to get Bagru’s artisans a Geographical Index tag, so no middlemen or frauds could claim credit for their craft. Vijendra dreamed of expanding his small workshop into a cooperative of many printers, but he just needed a client.

As luck would have it, in 2010 an American Fullbright scholar and textile historian introduced him to Lily Stockman, a painter living in Jaipur with a keen interest in traditional block printing. Vijendra’s rich knowledge of natural dye chemistry and Stockman’s blocky, minimalist design language was a perfect fit; after Lily’s sister, textile designer Hopie Stockman, visited the Chhipas to prototype new designs, Block Shop Textiles was born; which is now Vijendra’s oldest and largest client. During those early years, Vijendra had another visitor at Bagru, Jeremy Fritzhand, a recent Union College graduate and a Minerva fellow, who quickly became Vijendra’s “best friend, brother and business partner.”

“Jeremy explained that he could only apply for a grant to his college if we could come up with a way to help the entire community of dyers and printers at Bagru. This worked for me. I had always wanted to do something for my people,” said Vijendra.

Together, the two of them founded Bagru Textiles, which in addition to its all-natural appeal for the environmentally conscious, is also socially and economically responsible. In its current capacity, the company employs sixteen families of master printers, dyers, block carvers, dhobiwalas and designers, all of whom ‘pitch’ or come up with various designs that are put up on the Bagru Textiles webpage. If designers like their work, the family that made the pitch gets the bulk of work, at double the market wage rate. In addition, at least eight of the sixteen families are always occupied producing custom orders that designers send them — thereby expanding the aesthetic vocabulary of both producers, and consumers. Furthermore, a substantial portion of Bagru Textiles’ total proceeds go towards comunity initiatives for the entire Chhipa community in the village. This social impact approach is important to how Vijendra does business, and it’s important to his most loyal clients, too: Block Shop invests 5% of their profits into long-term healthcare projects they develop with the community. Last year they co-sponsored a mobile healthcare clinic for the entire Bagru community, and are currently installing much-needed water filters in the homes of all co-op members. For Vijendra, it’s not just business, it really is family.

While Fritzhand looks after the virtual logistics and site branding for the page, Vijendra communicates what designers want to his team or master printers by creating samples with his own hands in the workshop, for them to replicate. Bagru Textiles now prints for clients as far-flung as Los Angeles and Melbourne.

It’s been four years since Vijendra Chhipa last took his children on a vacation, but the lean, bronzed man with a wiry moustache never stops smiling once through our interview. The man who once wondered how he’d ever tell his story, is now visiting faculty and instructor at various colleges across the country, sharing with young, aspirational designers the secrets of his craft.

“Maybe, if the goddess wills it, we will grow bigger and I can hire someone to help,” he says. “At the moment, it’s very expensive to hire English speakers, and even I can’t afford to replace me!”

Vijendra, thank you for sharing your beautiful story and introducing us to your village’s traditions and craftsmanship. Vijendra hired his first English-speaking local manager two weeks ago. The future looks bright for him and the block printers of Bagru.

Head over to Bagru Textiles to find out more about Vijendra and Jeremy’s initiative.

Looking for more videos to watch? Browse all of the FvF Videos we’ve produced thus far. This is our first story from India but there’s definitely a lot more to explore there!

Video: FvF Productions

DoP: Andrew Kaineder

Director: Frederik Frede

Original Music: Infinite Rework

Text: Nishita Jha

Photos: Amy Tuxworth