Istanbul based Zeynep Erekli is unique, almost an alternative specimen of her species with light running through her veins instead of blood. She is luminous. Much like an arborist cultivating, managing and studying individual trees, shrubs, vines and plants, she explores streets, uncovers histories and attunes herself with current tendencies. She is a free-spirited soul and intrepid traveller. Impressions from her travels are distilled and translated into the magazine she works for, Bone Magazine. As one of the most eligible publishing coordinators in the scene, her dromomania knows no end.

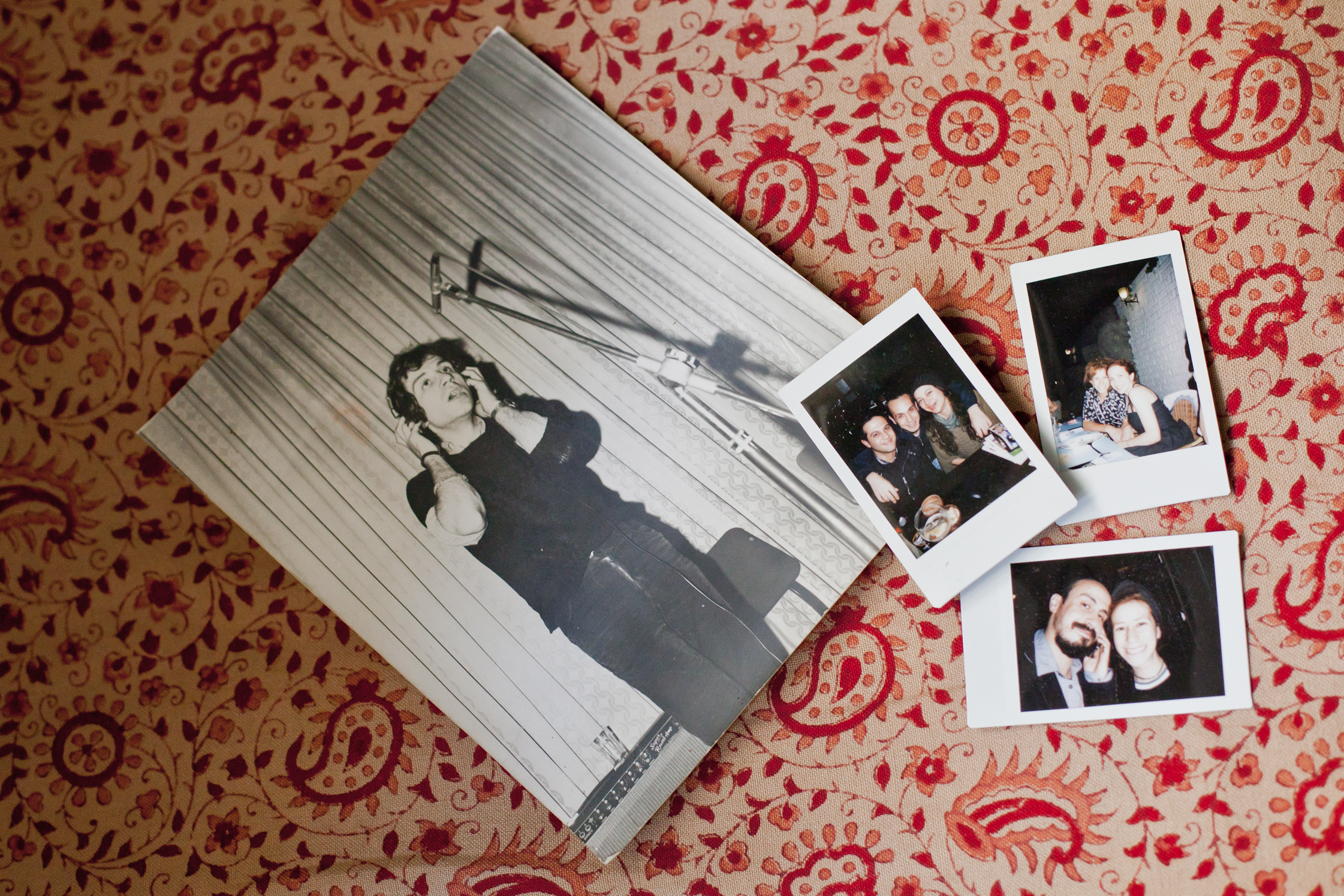

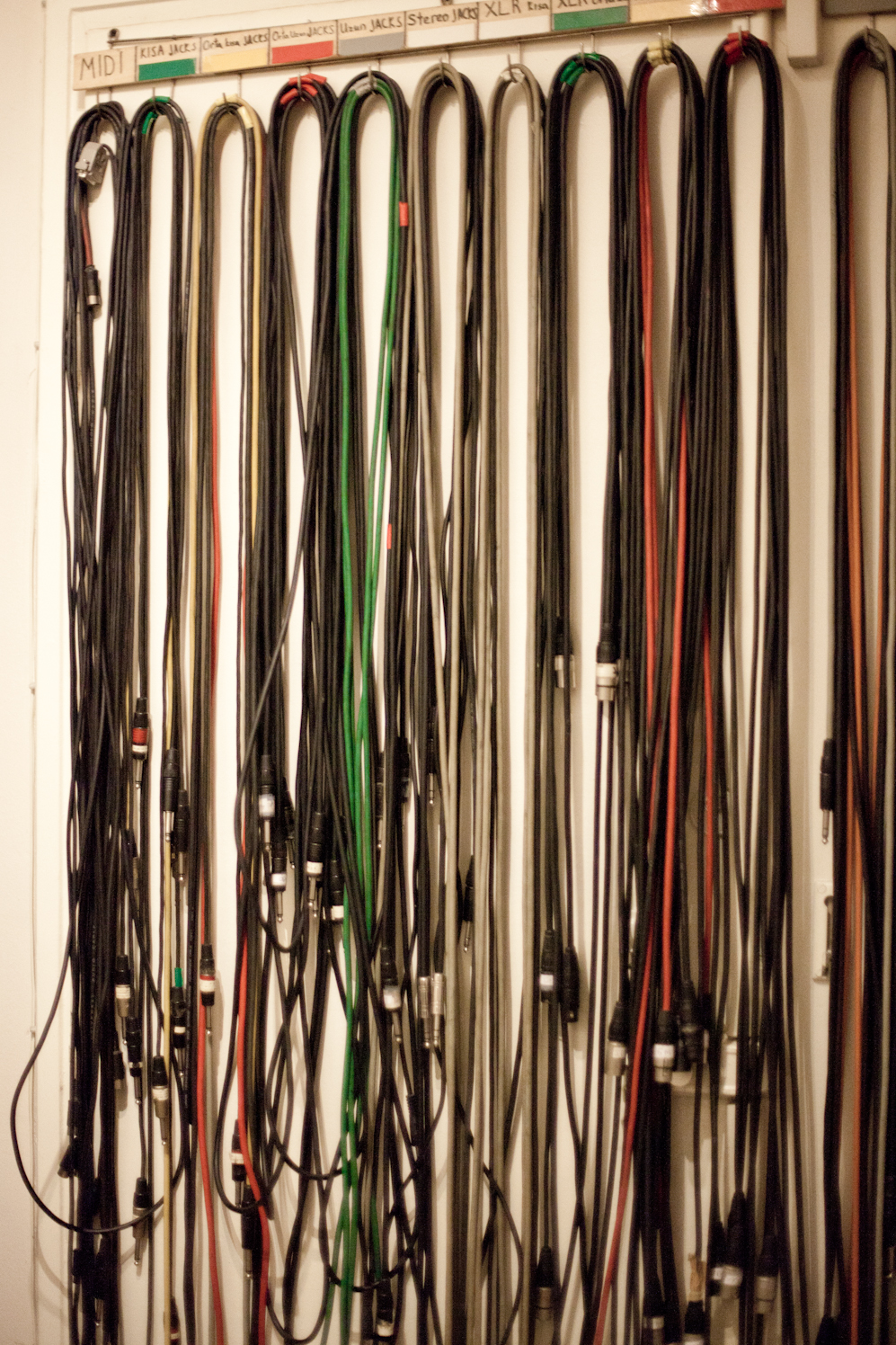

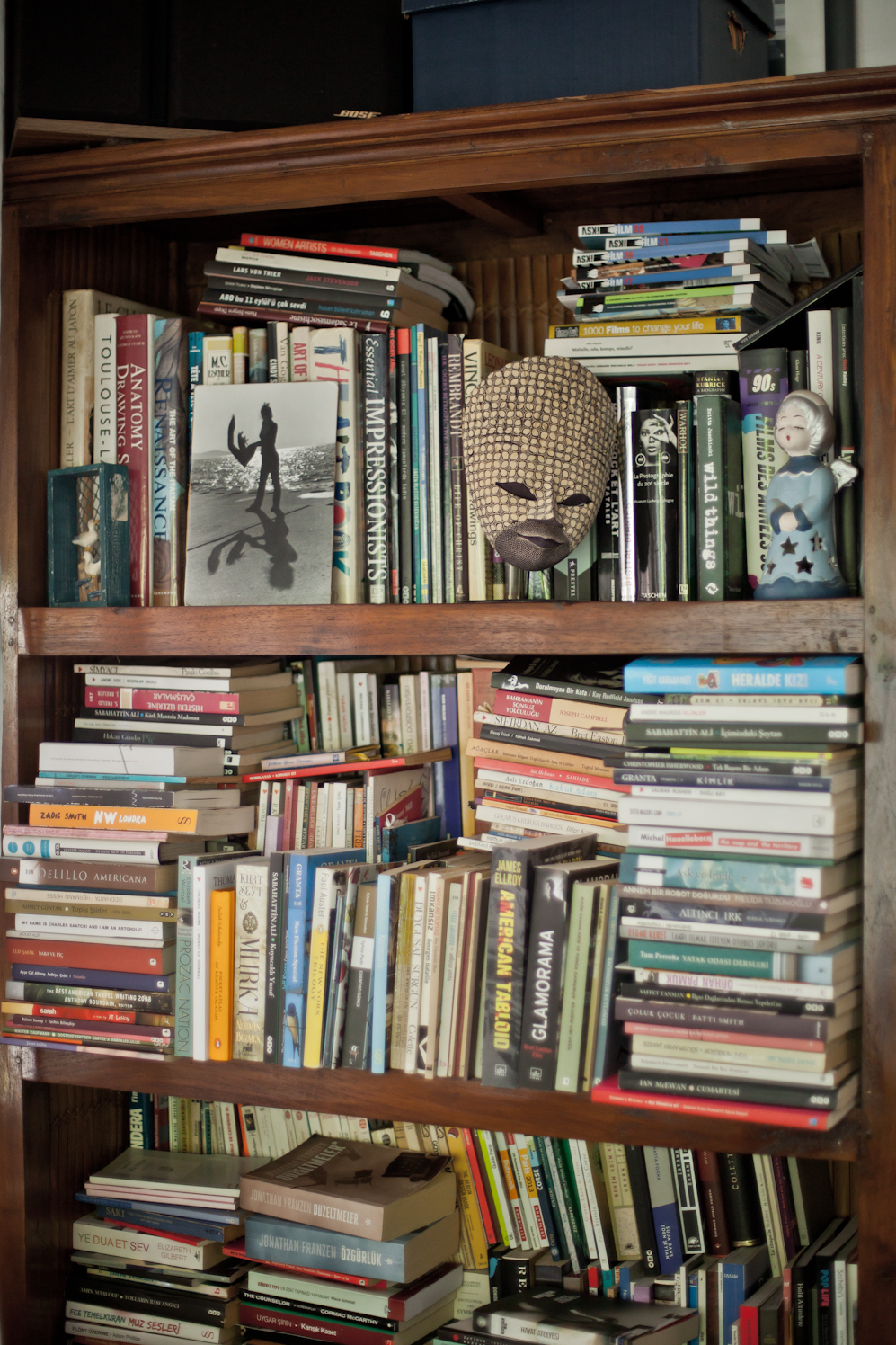

However, when she is in town, you can be assured to find her in one particular part of town: Moda. Her house is one of the most distinctive residences in this established coastal neighborhood. Located at the end of a long street, at a tiny intersection, the house is surrounded by windows and balconies that allow light to enter the interior from different angles at different hours of the day. Her father, R?za Erekli – a renowned producer, composer and songwriter – runs Erekli-Tunç Studios which is located on the ground floor of the building. The detached quarters reflect a nostalgic and subdued atmosphere. The elegant classicism of the surroundings convey a sense of welcome. Coffee tables and buffets collected by Zeynep’s mother on her trips to Pakistan and the Far East play a leading role. Strong family bonds are evident through countless photos and heirloom antique furniture. These connections are carried through in Zeynep’s character, influenced by her mother’s exceptionally warm hospitality and father’s captivating eccentricities. We see inside her world and gain some qualified travel tips.

This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who presents a special curation of our pictures on Zeit Magazin Online.

Where did you grow up?

I am from Kad?köy, Moda, born and raised. I attended Lycée Saint-Joseph here for eight years. My cinema obsession comes from Süreyya Sinemas? – currently functioning as an opera building – and Rexx Sinemas?, that is still here. I experienced the pleasure of being a barfly for the first time at Karga Bar which is still intact as well. I have a love for the streets and their melancholy and feel a connection to

rock ‘n’ roll and grunge. You could say I grew up to be a complete Kad?köy gal. To be honest, ‘growing up’ is the wrong word; because the very essence of being a Kad?köy person is the resistance against growing up or simply not wanting to.

How would you describe a ‘Moda’ resident? What are the main difference between other districts of Istanbul and Moda?

Moda is the dead end. This small district holds one end of Kalam?? Bay. The streets connect to the sea. It is not an artery. It is a nuisance to go around with a car especially in traffic, and this physical state is reflected in its character. The streets are old but clean. There are a lot of trees. Almost every house and apartment has a garden or a backyard. The animals on the streets are as content as a house pet. Nobody needs to sacrifice their habits or attitude. In this sense, Moda is not open to transition. Although the population is getting younger and younger, as far as I can see, there are no intruders to the soul of this place. Big city people can’t survive here, they get bored. People like to walk by the coast here, they own pets, and embrace an easy-going lifestyle. Moda’s coastal stretch is one of the few places in Istanbul where you can enjoy yourself without cars and crowds. I love to eat breakfast in a low-key tea garden. On Sundays I love to simply lie on the grass or go to Nefess Studio for yoga. Sometimes I go for some Rak? at Koço, which is an institution that was established in 1928, or a beer at Zeplin.

There is quite a history connected to this area isn’t there?

Intellectually, the history of Kad?köy, which includes Moda, goes way back before Istanbul’s history. During the Ottoman Empire, Moda was a neighborhood with many minorities coming from Europe. Essentially, most of the British people coming to Istanbul settled here. During the Westernization period, The Ottoman elite, Rums, bureaucrats, artists and scientists showed an intense interest in the neighborhood and slowly it began being referred to as ‘Moda’ (which means fashion in Turkish). One can still see the various architectural works, Western influenced schools and churches that bore witness to this process. Despite the transitions Moda preserves the characteristics of an upper middle class neighborhood.

How would you define your occupation?

Sometimes when someone asks me what I do, I simply say ‘travel writer’. Then comes the silence and the curious looks as it is not a common occupation in Turkey. I work in publishing. Until a few years ago, I would say ‘magazine publishing’, but now there is the Internet side of it with Bone. With the rise of social media, I found myself trying to understand and execute many different aspects in publishing. The funny thing is, I actually wanted to study fine arts. I failed to pass the exams for the classes I wanted to attend, so I applied to study French Philology, as my second talent was writing. In my free time, I interned for Time Out Istanbul magazine. After a short period, I got recruited and the rest fell into place. To be perfectly honest, I got stuck with publishing.

You have quite a strong and particular stance regarding your work. How did you shape it over the years?

I studied in a French Lycée. Perhaps my approach may have blossomed from a French influence. With teachers schooling you about humanism, Descartes’ Cartesian Theory or Camus’ “Le Mythe de Sisyphe” at a young age, it allows you to conceptualize things differently. No wonder this makes you stronger. I became an editor at Time Out Istanbul in 2001 and I was a novice in such a dynamic structure. I remember running through Istanbul for interviews, chasing news and coming back to the office for preparation and typesetting. Most of my friends were at university and they hadn’t quite figured out what to do with their lives while I was wrestling with deadlines, insufferable art directors and constant phone calls from the print shop saying “Come on now, we are waiting for the documents!’’ These experiences instilled a strict discipline and work ethic. So I was injected with this particular standing throughout my career. The motivation you need either for work or in your personal life does not lie in the outer world, but within.

How did this stance evolve?

Stance is a very strong word, especially in Turkey when you do not have so many options. In Turkey, it’s very problematic to work in the media. It is impossible to separate it from national culture. During all periods and in every aspect, the media has been used as a tool by government elites. Especially now with what Turkey is going through, it is heart breaking for me. I can honestly say there is no newspaper I can read. I read columnists instead. A monopoly has been reached via corruption and a total moral breakdown has spread out from government to media, and from media to the public. I am on the lifestyle and travel side of it, but even in this particular area, you can feel the waves of this current. Going back to my own career, perhaps, if I had taken more political steps, maybe I would have had a column in one of the daily newspapers by now – but then I have no intention of doing this. Working independently is hard but rewarding. The creative agency I am a part of now, Dukkan Publishing, protects its position of independence and tries to make its business as ethical and respectable as possible.

Would you describe yourself as a workaholic?

I became the Turkey correspondent for Travel + Leisure in 2006, and during that time I only travelled and wrote articles. Work was the center of my life, nothing else. But for the last two years I have been working for Bone, I broke the habit of being a workaholic and the obsession of thinking about work all the time. It is healthier this way.

What defines you individually, apart from being a publishing coordinator?

I travel abroad a lot and I am in the center of the most active part of the arts and culture scene in Istanbul. My life seems very colorful but if you ask me, it is very simple. I have a small and sweet group of people I see regularly. I stay at home unless there is an interesting event on. I practice yoga regularly. One of my short-term goals is to receive my yoga instructors certificate. The ‘human carnival’ is a bit too much for me, because of the current status in Turkey. It has made everybody neurotic and insane. After the Gezi protests, everybody around me changed spiritually and delved into another state of mind, filled with pain and concern, and naturally I am a part of it as well.

Can you tell us about your personal style a bit? It seems it is reflected in your endless energy and pragmatism.

I follow fashion but not religiously. I do not like the prototyping aspect of it. Having said that, I do not think I can say I own a particular style, an eclectic taste maybe. I wear hoods, bandanas, shawls, hats and capes. I like flowing loose clothes, maybe because I am a mobile person. I love music and dancing, I like errands, climbing a ladder two-steps at a time. These accessories correspond to that. I mostly wear black in winter and color in summer. I do not like heels or bags. The way I see it, style is about vivacity or melancholy, a self-expression, and something bought from a boutique does not add to that feeling.

In your opinion what is the basis of creating a solid audience for a travel and lifestyle magazine in Turkey?

Working a lot, creating the right language on every page, line and throughout every photograph. These are the ingredients for a consistent high quality publication. The audience follows your tips eagerly when you show them details that do not exist in mainstream travel publications. For example, rather than pointing someone in the direction of the Hagia Sophia Basilica when visiting Istanbul, it is a far more valuable to point out the Kariye Museum, and wander around the Balat neighborhood while nearby. Travellers do not have very much time. It is important to be precise and thoughtful with content. Readers notice this.

What do you think are the elements that add value to a hard copy publication in the age of Internet?

The need to touch paper is an emotional bond. In order to sustain print publishing, this bond must be fed. In order to produce quality content, detailed reporting and contacting interesting people face to face are important. Delivering striking photography and rigorous page designs encourage a reader to buy a magazine. If a reader is genuinely interested in a topic they will archive that issue. An example is the Nuri Bilge Ceylan interview that was published in Altyaz? cinema magazine. It was published just after his movie ‘K?? Uykusu’ won the Palm d’Or award. The interview was amazing and I wanted to buy the issue and archive it myself. The only way out for print media is power and prestige. Print must do well by prestige.

What can you say about magazine readers in Turkey generally?

The biggest magazine audience in Turkey is made up of magazine employees! I am serious. All the publishers and editors from the 90s and the beginning of millennium still buy all the fashion-music-travel-agenda magazines. From my observations, the new generation does not have the same feelings, curiosities or motivations. They are not interested in what others do. They live behind computer screens immersed in the Internet. In a broader sense, reading habits are insufficient. You could say this is only natural, as people’s first priorities are justice, environmental politics, education, human rights and safety in their town and country. Reading a magazine can be a luxurious treat for our people and this is no surprise.

Of all your travels, which city has influenced you the most?

Tel Aviv. When I was writing an article on the city, I used the words ‘fragile and hedonistic’ to describe it. Why would a person visit a city under the threat of a bomb attack? The answer lies in the bones of a traveller who wants to understand the history and the soul of a time. The irresistible pull of problematic metropolises such as Tel Aviv, Beirut and Istanbul exist in their character and the electric wires surrounding them. A unique hedonism, a rare joy of living, and a different kind of humor, flexibility, tolerance and a pulse you cannot find anywhere else are located in cities like these. Israeli politics have a tendency of favoring the right, but Tel Aviv youth is liberal. Observing this was awe-inspiring. Now we are watching Israel’s operation for Gaza with sheer terror and concern. I talk to people I have met in Tel Aviv. The rebellious feelings towards the system and the effects are parallel to our own.

You have travelled all around Turkey. What are your favorite cities and locations?

Everywhere is extraordinary in Turkey and I don’t say it in a patriotic sense. Especially the eastern cities. Southeast Anatolian cities and villages can give you goose bumps. Mardin on the border of Syria means one thing to me: true love. It’s an antique city standing up to time and the ferocity of civilization. The air you breathe makes you feel alive. Historical locations are spectacular. You can also find the most delicious kebabs in Mardin. Another place I would like to mention is the famous archeological site in Urfa, Göbeklitepe. The archaeologist, Klaus Schmidt, who found the site, died recently and I am curiously following the proceedings of the diggings now. Also, the small island Bozcaada in the Aegean Sea, five hours drive away from Istanbul, is a place I love passionately. I visit it a couple of times every year. I feel like I am at home there.

What are some of your must see destinations in Istanbul?

Istanbul is a monster. Kuzguncuk is a little gem on the Anatolian side of the Bosphorus. It is an elegant neighborhood with many trees and little churches. I would suggest taking a route to good old Karaköy, Eminönü and then walking to Beyaz?t. These are places where you can observe the new world chaos fused with the old Istanbul. But if I had to choose one, I would take a boat and go to the Prince’s Islands. My favorites are Burgazada for taking a walk and Heybeliada for cycling. A visit to the library of Heybeliada Seminary followed by dinner at Mavi is also recommended. Istanbul has fabulous options for eating out. I also love Munferit for its modern Turkish ‘meyhane’ vibe and its interesting new generation meze (traditional Turkish appetizers). For lunch ?imdi and Gram in Asmal?mescit are also great and for a drink in the evening Journey in Cihangir is a favorite.

Zeynep it was a delight to spend time with you. A big thanks for your genuine hospitality. Find out about the agency she works for here and Bone magazine here.

Photography: Ekin Özbiçer Güney

Interview & Text: Heval Okçuo?lu

For more stories in Istanbul you can look here.