There’s a rich rumble to Ralph Steadman’s voice when he recites Shakespeare. Noticing that the audio recorder has been turned on, he breaks mid-sentence to reel off a verse from Macbeth with hushed gusto.

“…Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.”

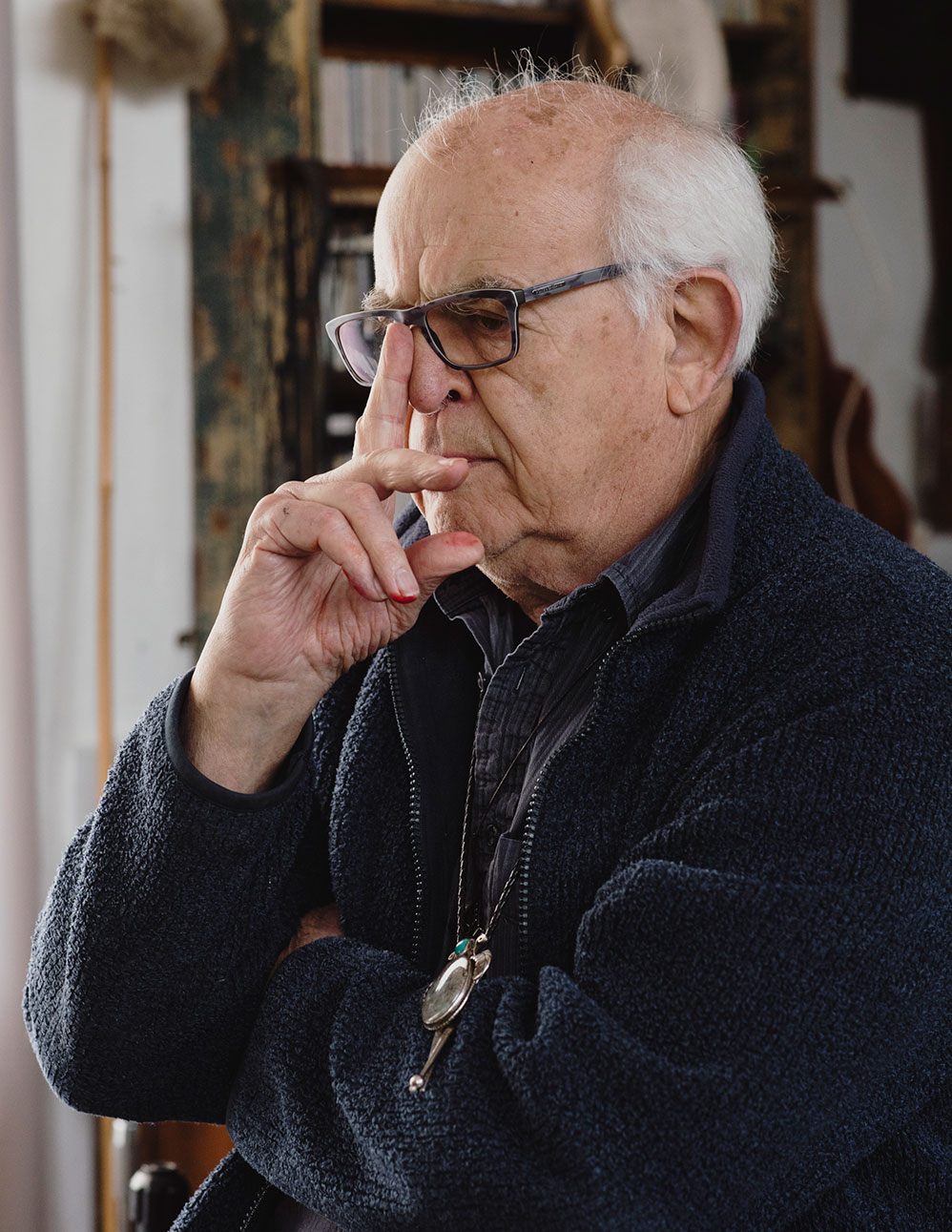

When he’s not reciting Shakespeare and 20th century nonsense poems, Ralph speaks of the Kent village where he has lived since the early ’80s. About Leonardo da Vinci and Louis Armstrong and William S. Burroughs. About ‘Hunter’, of course. Occasionally, he gives a direct answer to a direct question, but only very occasionally. It is in freewheeling form that Ralph is at his most vibrant. It is in the unexpected outliers of his instinctive approach to art, and interviews, and the wider world, that Ralph is at his most insightful.

This portrait of the exuberant illustrator was produced in collaboration with Sonos and is part of our series exploring the impact of music in inspiring individuals’ lives.

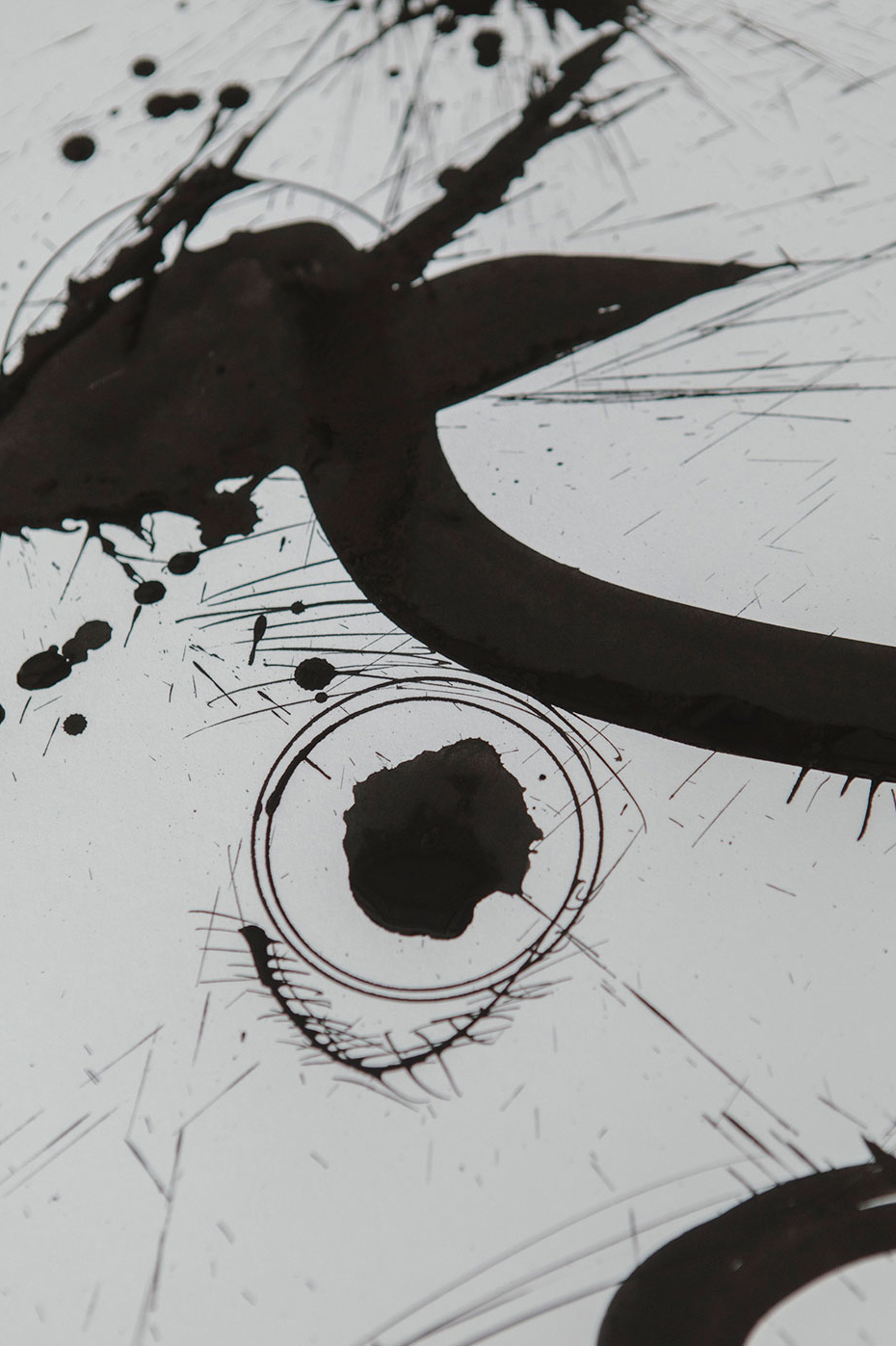

Sound and fury. It’s a phrase that hangs in Ralph’s studio long after the words have left his mouth on this particular morning, capturing something of the work that fills the space. Standing at his desk, he is surrounded by ink-flecked tools and paint-splashed memorabilia. Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes blare out via a cassette tape. He looms protectively over the spotless white sheet of paper placed in front of him for some time.

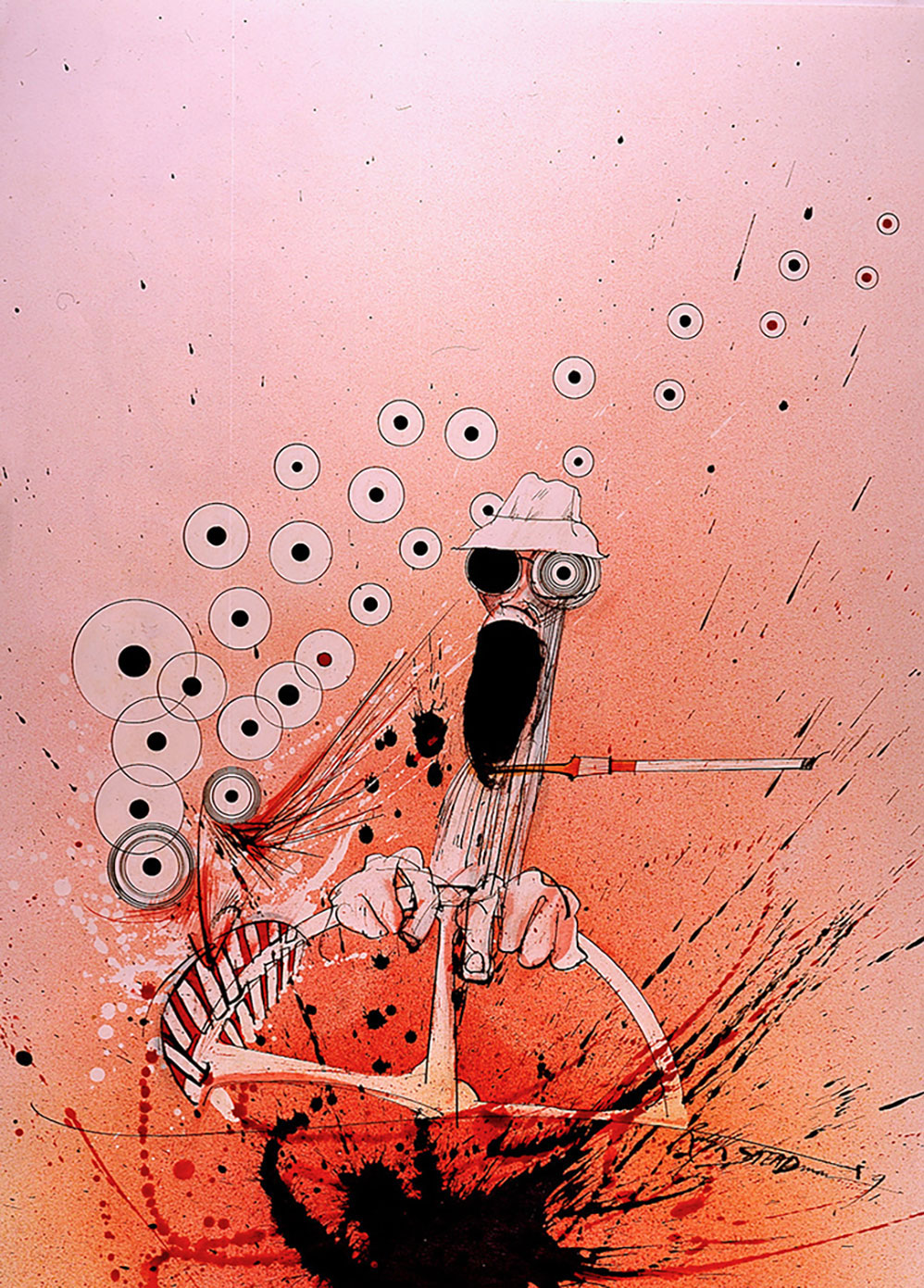

“Really, you should capture the paper now, how it is,” he says. “Look at it! How beautiful and pure…” Already though, one hand has moved to a small pot of black, acrylic ink into which he then plunges a stiffly-weathered paintbrush. The blackened brush is lifted with a studied flourish before hurtling down towards its bright, blank target. Thwack! Odds and ends, odds and ends, wails Dylan in the background. A dense mass of ink coagulates at the point of impact. Spotted trails of black spew forth in different directions.

Sound and fury. Out, out, brief candle! Ralph takes less than a second to appraise his handiwork, holding the inky shape to some unknowable personal standard, already preparing the brush once more. “Oh, that’s good! That’s a really good one…” Thwack!

Later, he adds great circular eyeballs to the face that has begun to form on the page—meticulously round thanks to the protractor he employs for this part of the process. “I actually studied technical drawing because I had originally wanted to make aeroplanes, believe it or not,” Ralph explains. “That’s where the protractors come from, and the very straight lines that I would also use in my work [alongside the splashes of ink and brushstrokes].” He pauses, before adding, “working in a factory though…it wasn’t for me, I couldn’t get along with it.” He doesn’t say this archly, with his eyebrows raised, but utterly seriously and almost apologetically, as though the fault lies with him, rather than the creativity-stifling monotony that so many would find unbearable in production-line work.

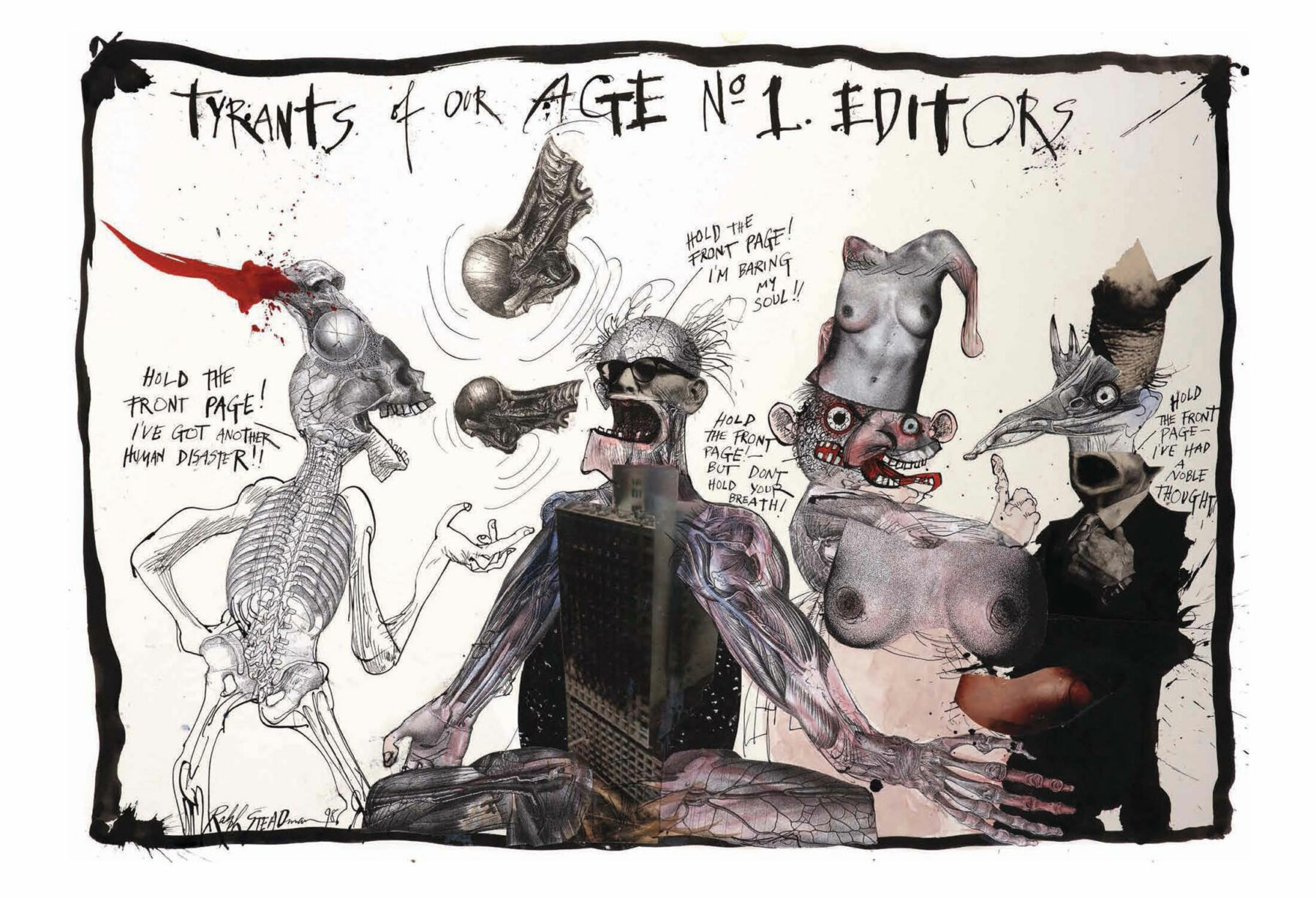

There are other quiet, tender moments like this dotted across Ralph’s dramatic storytelling and musings. They can take you by surprise, contrasting as they do with the savagery of his brush strokes and the fierceness with which his work can attack its targets. Initially, for example, he is less than enthused about beginning another piece of work, stating with some remorse that these days he sometimes considers himself, “a pollutant”, creating ‘unnecessary’ pieces of art almost for the sake of it. “You know, I always wanted to change the world with my drawings, but did I? If I did, looking at the state of it now, it was for the worse.”

The fire still burns, however, when the mood takes him, or a particularly interesting commission comes along. Ralph still lampoons political figures occasionally in the pages of the left-wing British weekly, the New Statesman, and when conversation turns to the topic of Trump, Brexit and the previous British Prime Minister (“that dreadful Mr. Cameron”) there are flashes of the same unabashed distaste that he famously employed when railing against Nixon and the Vietnam war.

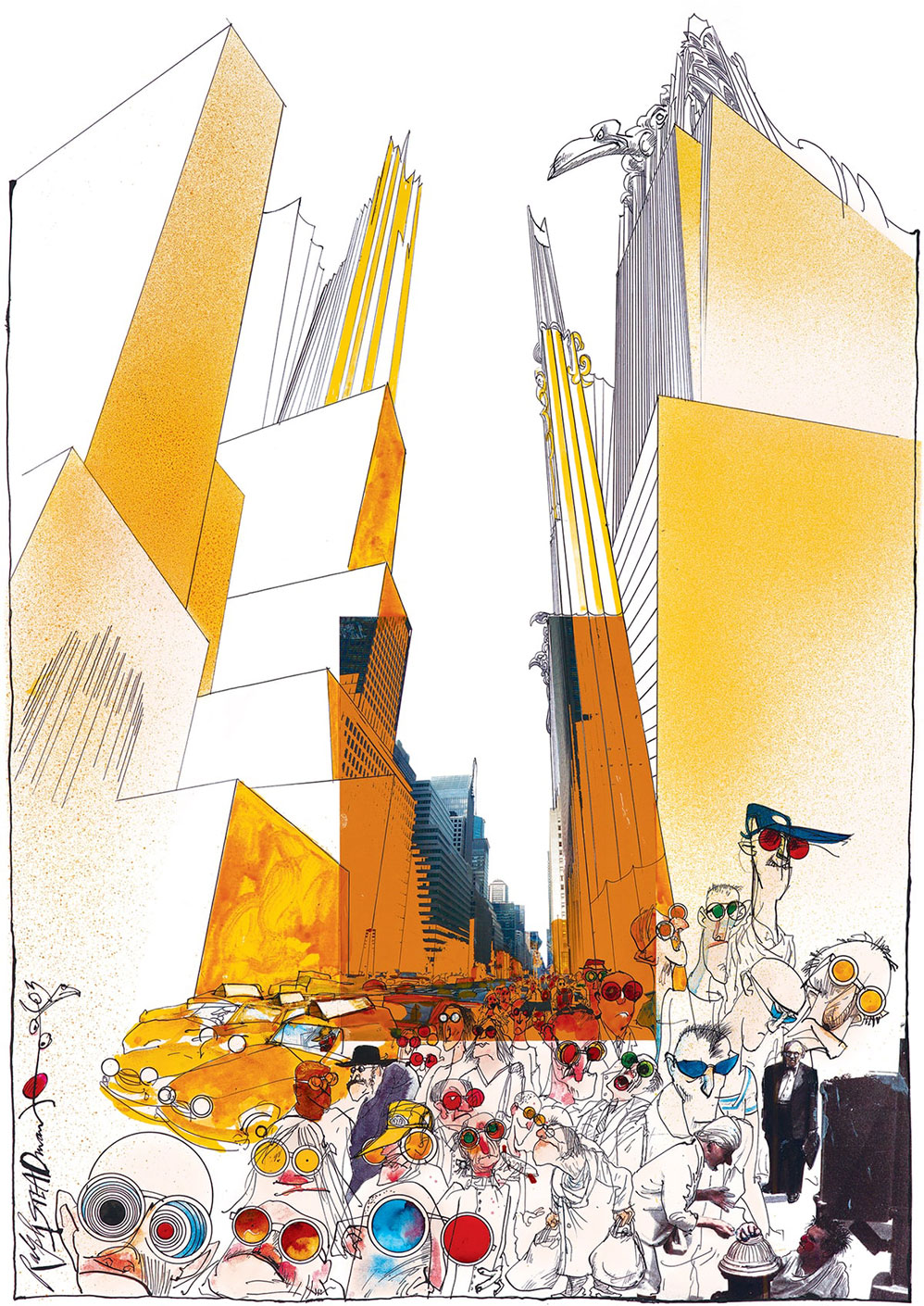

Those targets were of the ’70s, of course, when Ralph’s work was a common fixture across the pages and covers of Rolling Stone. It was the short-lived American publication, Scanlan’s Monthly, however, that first brought Ralph into contact with his most (in)famous partner in crime, Hunter S. Thompson. Sixties flower-power was in its death throes, and Ralph had upped sticks for the states, where he discovered a new lease of life photographing and drawing the vagrants of New York City. While there, he received a call from a mysterious ‘Mister Suarez’, who, in a heavy Brooklyn accent that Ralph still mimics perfectly today, informed him that, “this writer who used to be a Hell’s Angel and had just shaved his head was going to cover the Kentucky Derby for Scanlan’s and would I like to accompany him?”

“I mean how remarkable, it was my very first visit to America, and on that very first visit I ended up meeting the exact one person I needed to meet in this world…”

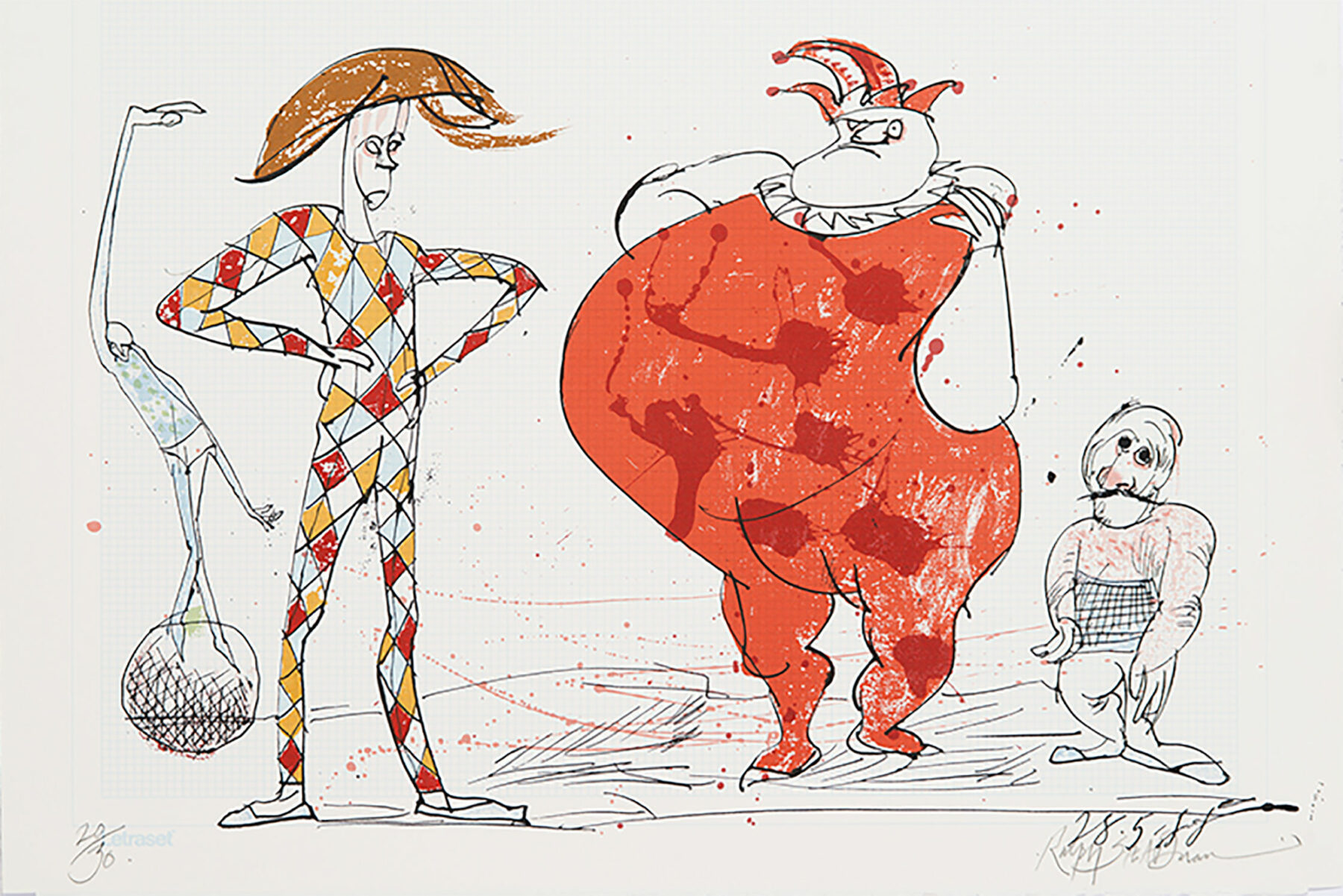

What ensued was a weeklong bonding experience of a bender, enacted by two conflicting yet somehow kindred spirits. Each was obsessed, via their own mediums, with exploring the dark underbelly of Americana. Ralph’s illustrations of the Derby became instant archetypes. The lustful American greed embodied by fat-cat racehorse owners. The freakish proportions of the jockeys squashed against the spines of contorted horses. The horses themselves, all animal aloofness and engorged phalluses.

Paired with Hunter’s searing, mischievously confrontational words, the piece that appeared in the June 1970 edition of Scanlan’s was later heralded as the birth of Gonzo journalism. A year or so later, when Ralph had returned to England, Hunter sent him a copy of what was to become his new, career-defining book, along with a request for accompanying illustrations. It was titled Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, and first exploded from the pages of a Rolling Stone serialization in 1971. The rest, as they say, is history.

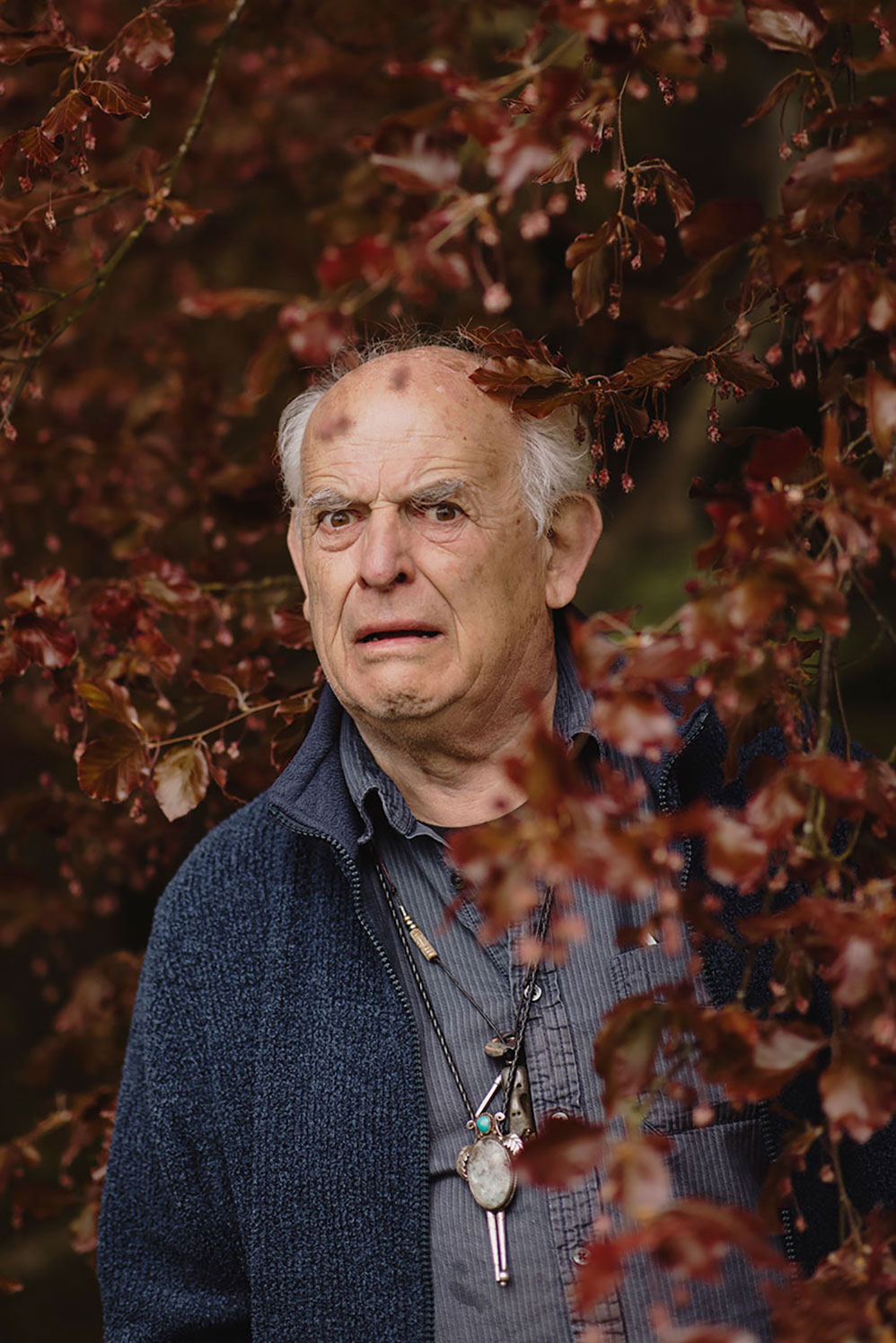

(“I mean how remarkable,” says Ralph towards the end of the day in another moment of softness, while meandering through the gardens that surround his home. “It was my very first visit to America, and on that very first visit I ended up meeting the exact one person I needed to meet in this world. Really, it’s remarkable…”)

“Hunter said to me, ‘Ralph! Don’t write. You will bring shame upon your family.’ He thought that writing was his thing, I suppose.”

The tales of Ralph and Hunter’s various Gonzo escapades are pretty much folklore at this point. And yet, hearing them afresh from Ralph’s own lips, a sparkle in his eyes and various Native American curios jangling from necklaces around his chest as he talks, it’s impossible not to want to share them.

“Now, see that photo there,” he says, pointing to a faded black and white photo of an oblivious naked man with his back to the camera. “Who do you suppose that is? It’s Louis Armstrong! I took that when Hunter and I were in Zaire [now the Democratic Republic of Congo] to cover the fight between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman.” It’s an odd, but perfectly understandable memento to have held on to, given that Hunter and Ralph never actually made it to the most famous boxing match of all time. Hunter, it transpired, had sold their tickets in order to buy a bag of weed, and Ralph was forced to watch the fight from the hotel bar, sketching away with only a crummy television set as his guide.

Or how about the time they were sent to cover the prestigious yachting race, The America’s Cup? It was a ‘sport’ that neither character had much interest in, and their reporting peaked with a midnight jaunt out to the docked yachts in a rowing boat. Ralph was armed with a can of spray paint and the intention to graffiti FUCK THE POPE along the side of one of the yachts – “for no particular reason,” he says, chuckling. Inevitably, they were caught in the act. Hunter, wild-eyed and under the influence, fired off a flare gun into the crowded port; chaos ensued.

Of course, years—decades—have passed since these events took place. The friendship between Hunter and Ralph stretched into the 2000s, even if the madcap actions that drew them together had become by that point increasingly unsustainable. Today, we break for lunch at The Chequers, a picturesque village pub a few minutes from Ralph’s home in the village of Loose. Over a plate of Proper Pub Fish And Chips, Ralph tells the story of when he brought Hunter here for the first time. “He wanted a glass of Chivas Regal and I told the barman discreetly, ‘you’d better make it a double’. The barman poured a generous glass and when it was placed down in front of Hunter, he just looked at it and said…” – here Ralph drops his voice into a perfect approximation of Hunter’s gruff timbre – “’…is that the free sample? Where’s the proper serving?’” The story is told with warmth and affection, but one wonders about the increasing effort it presumably took for Ralph, relatively sober for most of his life, to negotiate the excesses of his dear friend.

“Oh, I love Duchamp, love him,” says Ralph. “He was playful and mischievous – you could certainly draw a line to Gonzo [from his work], certainly…”

On February 20th, 2005, Hunter took his own life. “Take your phone off the hook,” Ralph was told, “Hunter’s just shot himself.” One year on, Ralph began marking the event in his own private way, jotting down the exact time and date of Hunter’s death on a sheet of paper before embarking on a new piece. He created commemorative pieces every 12 months for the next six years—works that remain private, that were, Ralph says, “for Hunter.” But it is clear that that the experiences he shared with Hunter are still never far from Ralph’s creative process. You can see it in the GONZO license plate that sits propped in front of Ralph’s workspace; in the kitschy Americana artefacts that Hunter gifted him over the years. You can feel Hunter’s mark in every one of the works that spill in reams from the shelves and surfaces in the studio.

Ralph is returning intermittently to the piece he started that morning. Every now and again he heads over to his Hi-Fi system—a hodge-podge of archaic equipment enlivened by modern speakers from Sonos, who are hosting an exhibition of record covers designed by Ralph in their flagship London and New York stores. He pulls out various cassette tapes, CDs and records to accompany him in his work. First up: a Django Reinhardt CD, to which he air-guitars an approximation of Django’s distinctive two-finger playing style. He explains that, “Allan Hodgkiss, who used to play with Django, actually taught me the guitar.” At one point, the studio is filled with the voices of Richard Hamilton and Marcel Duchamp in conversation, on a cassette tape with beautiful cover art. “Oh, I love Duchamp, love him,” says Ralph. “He was playful and mischievous – you could certainly draw a line to Gonzo [from his work], certainly…”

The last thing that Ralph plays that day, picked out from a cabinet full of vinyl, is a bright red 7” containing two recordings that Ralph himself made. Each comes from a period in the early ’80s when Ralph’s work began to fixate on one of his heroes, Leonardo da Vinci. In 1983 he published I, Leonardo, a first-person narrative book about da Vinci that Ralph both illustrated and wrote. As the stylus bounces lightly onto the record with a gentle crackle, Ralph says with a smile, “Hunter said to me, ‘Ralph! Don’t write. You will bring shame upon your family.’ He thought that writing was his thing, I suppose.”

The first song starts up, and for a moment the noise that fills Ralph’s studio appears to melt away, so that all that remains is Ralph himself, standing silhouetted against a translucent drape, through which the late afternoon light is pouring. His eyes are trained on nothing in particular and he begins to sing softly to himself. As the chorus hits, his voice grows surer, each word of the song’s title cutting through the background recording. It’s a title taken from a Sigmund Freud quote about Leonardo da Vinci, one that had a profound impact on Ralph. It’s called, ‘The Man Who Woke Up In The Dark.’ In Ralph’s incredible, singular world there is often sound of some description. There is not, however, always the need for fury.

For years we have glimpsed into the work and home lives of creatives worldwide. With each visit we have discovered something new, but what we’ve found everywhere is music. The collaboration with our friends at Sonos is special. We’re venturing inside Creators Homes, discovering what drives their passion in their chosen pursuit. For more from the artist Ralph Steadman see his website.

With advances in technology, the way that we listen to music changes. Independent of personal taste, Sonos is the home sound system. Learn more here.

Text: James Darton for FvF Productions

Photography: Ramon Haindl for FvF Productions