To Sophie Unwin, Founder and Director of Remade Network, circularity is grounded in social justice. Since 2008, her social enterprises have partnered with communities around the UK to put “radical” repair culture in service to people and the planet.

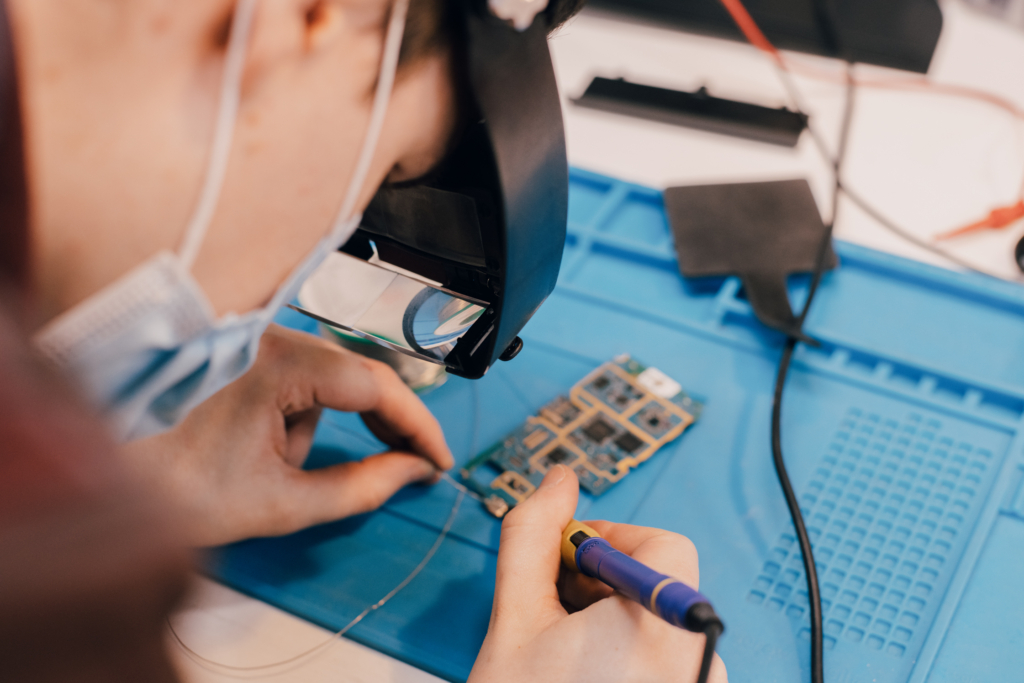

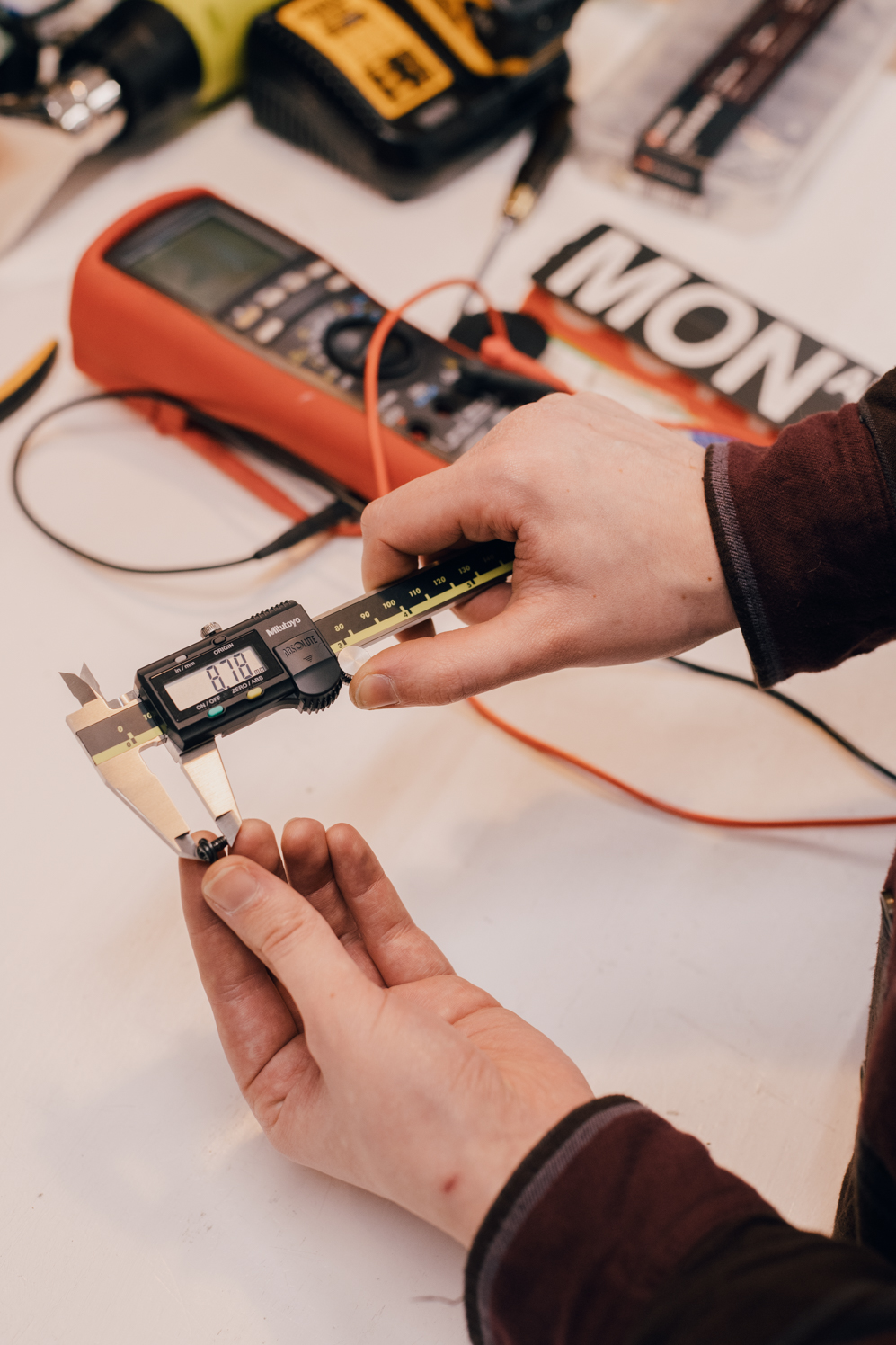

If it’s broken, fix it. Over the decades, this radically simple principle has been abandoned in the tailwinds of capitalism’s rampant trajectory. Charting the course for its revival is Remade Network, the three-year-old Glasgow-based social enterprise empowering community agency and digital inclusion through electronic repair, recycling projects, mending workshops, and job creation programs.

For Remade’s Founder and Director Sophie Unwin, the seeds of circular thinking were sown at the tender age of 18, when she set off to teach English in a remote village in Eastern Nepal. After a year of learning from a society that foregrounded community ties and the environment, she returned to London with intense culture shock at the superfluity of consumer choice. This transformative experience set off Unwin’s journey towards repair revival, which manifested early on in projects such as the Brixton Remakery—a reuse hub opened in 2008 amid the peak of the global financial crisis and during a time when the notion of repair was far from a priority in the mainstream.

Fast-forward to 2022, Remade Network is three years old and scaling up its impact. Between tech drops and city council meetings, Unwin takes the time to share her personal journey to repair culture, her passion for renegotiating power dynamics around community agency, and the importance of valuing the unseen work of women who have been cultivating circular economies of care all along.

This interview is part of “Circular Views”, an editorial series produced in collaboration with subscription-based furnishing company NORNORM. Spotlighting innovative thinkers, each interview explores a different dimension of circularity with the goal of raising awareness and fostering a creatively driven movement rooted in circular practices.

“It’s not a new idea to fix and mend things. It’s as old as time.”

-

What does the circular economy mean to you, and how does repair culture fit into the picture?

Repair culture encompasses a lot of different things which are all about preventing waste at the source rather than dealing with it downstream. With Remade Network, I’ve been motivated by repair culture’s social justice dimension in addition to its environmental one. It’s not a new idea to fix and mend thing, it’s as old as time. For me, the circular economy is about creating redistributive economy where wealth stays within communities or gets distributed to reduce inequality. Inequality is so linked to climate change that I don’t think we can fix the wider issues if we just see circularity as a technological or business efficiency goal. It’s a whole societal shift that’s needed.

-

You spent a formative year living in Nepal. What did this time teach you?

Practical skills weren’t particularly valued in my family or education. It was all about academic achievement. When I was 18, I spent a year in a remote village in Eastern Nepal, 24 hours away from Kathmandu and close to Darjeeling, India. It was a time before they had running water or electricity. That year of living showed me what I lacked. I thought I was going there to teach young people English, but the syllabus was so inappropriate for their needs. It was Chekhov’s short stories, and these kids just wanted to be able to have a conversation, go to the capital, and get a job.

It became clear that we were learning a lot more than we were teaching. We were learning how to cook, how to fix things, really practical stuff. Because we were remote, and because it was expensive to buy new materials, things like plastics were really expensive. It was a different kind of economy to the one I’d left back in London. Our little kerosene stove would always break down, and we’d always go get it fixed rather than buying a new one. We’d get our vegetables unpackaged from the market and refill our containers, and get milk straight from the cow. Everything was refilled, reused, repaired.

-

How did this experience change your perspective on Western consumer culture?

Society there had so many other things I’d lacked. It’s not about romanticizing poverty—it was a community set in a tea plantation. People generally had enough to live on and there was such a strong sense of community. There was a really clean local environment and beautiful air quality. I came back to London and went into a supermarket and saw 20 types of coffee, and had worse culture shock than I’d had going over there. The idea that consumer choice gives you everything you need felt like a fallacy.

With our current economic model, we create so many problems that we then have to fix down the line. Why don’t we prevent them in the first place by valuing other things—not just valuing economic growth, progress and “development”, but valuing community and the environment equally? I thought I was going there to help people, but I didn’t feel that. It changed my previous thinking that “development” is a top-down thing. In fact, it can be quite an imperialist project, and I hadn’t seen that side of it before.

-

From that turning point onwards, could you share your journey towards founding social enterprise initiatives, from Remakery in 2008 to Remade in 2018?

This experience made me shift my idea of what I wanted to do in life to environmental work. I did a Master’s in Sustainable Development, and got a job for an environmental charity where they had funding on a project basis—when the funding ended, the project ended. It frustrated me, because I wanted to do something that was going to last.

At the time, I lived in Brixton, South London, where there was quite a lot of poverty. It was 2008, the time of the financial crash, and we were bailing out the bankers. My neighbor was an elderly Afro-Caribbean man who fixed bikes in his front garden. I found it depressing that he was doing something that’s really needed, like fixing bikes, but he was obviously struggling. I thought, ‘Why aren’t we valuing the people who are actually doing the things that we need, like repairing things, and how can we make it into a model that’s viable?’

I became interested in setting up a social enterprise model or a business model, which I talked to a lot of people about. The majority said to me, “Sophie, it will never work, because it’s so cheap to buy new. Why are people going to pay to fix things?” So I started thinking, ‘Well, what will people pay for?’ They’ll pay for learning. If you set up a project that’s about education and repair education, as opposed to just repairing things, maybe that’s the business model. So it evolved through the community having conversations.

-

Why do we need to reevaluate our relationship with the objects that surround us?

Because we can’t continue to consume three planets’ worth of resources when we only have one planet to live on. The emissions we’re creating are too much for Earth’s capacity. We’re at a tipping point in terms of catastrophic climate change, which is going to be devastating if we don’t reverse it. We don’t only need to think of the negative side, though. Doing things differently can bring many benefits in terms of building communities, improving wellbeing, and valuing our relationships. It can give us a lot of satisfaction. Buying things that last, looking after them, and mending them—learning those skills is really satisfying.

People come to our workshops to learn how to fix things and gain a new skill they can keep using. One of our customers said something which I really liked: “We need to learn how to look after our everyday things, because our everyday things look after us.” It’s like your favorite coat. The lining breaks, and it seems easier and cheaper to buy a new one. But if either you know how to fix it or you know someone who can fix it, then you keep the coat that you love. When we throw things away, they’re out of sight, out of mind. The whole process is invisible. We don’t know what’s going to happen when we throw something away, which landfill site it’s going to end up in, or, if it’s electronic waste, if it’s going to be shipped overseas, if it’s going to be dismantled in really unsafe conditions by a worker in Africa.

We might know in the back of our minds that slave labor and unethical practices exist, but we’re not confronted with them in a daily way. We’re closed off from all these possibilities in this fast-paced consumer lifestyle. When we slow down and take the time to look after the things that we have—and look at other ways of using things, like renting, hiring, sharing, swapping, as well as repairing, we can gain a kind of better sense of wellbeing and peace that we’re treating the planet better, and also treating other people better in the process.

-

On that note, what might this mindset shift imply for our relationships and communities?

I’m interested in the dynamics around power and agency within communities. It’s not about seeing a community as a recipient of something, but rather as a kind of democratic body of people who want to restructure society so it’s fairer. One of the key ingredients for doing that is to create a society with less inequality. And that means resources being situated locally, so communities have control over the resources within them—both skills and material resources.

The term ‘community’ can be used in quite a tokenistic way. What does it really mean? It means people, local people. What is happening in each community is going to be different, so what are their needs? I view how Remade has developed as a partnership with local communities. For example, in Glasgow, we have a contract with the City Council for their old computers. We refurbish and redistribute them. Our contract specifically states that all benefits need to go to communities within Glasgow. It’s about tapping into the needs in that place and then designing solutions together.

-

Could you share more on how this initiative—the Desktop Distribution Project—originated, and how it contributes to fostering social justice?

We hadn’t planned it—it came out of the pandemic. Originally, when I got the contract with the Council, it was a commercial relationship where we would dispose of their computers safely and securely. We thought we’d be opening a big center for people to come in, do repairs, and learn skills. We were about to sign a lease, then Covid came, so we couldn’t go ahead.

At the same time, it was clear how reliant people were on access to a computer to get online, to access basic services, education, youth groups, even just staying in touch with families. This need isn’t new, but it was really exacerbated by Covid. . So we pivoted our direction. Instead of selling refurbished computers commercially to individuals or as part of contracts to other businesses, we were effectively creating an internal market and redistributing them to people who needed them.

Once we started, it just kept growing. It worked well because we did it in partnership with local communities. A group could say, “We represent refugees in the city. We know who those individuals are. We know that they need 20 computers. We’ll make sure that they get to them.” We’ve now distributed around 1500 computers, with another thousand set to go out in the next few months. From a cost perspective, but also environmentally and socially, it seems beneficial to reuse and refurbish what you already have.

“We can’t continue to consume three planets’ worth of resources when we only have one planet to live on.”

-

Why is it important to spotlight this type of work in light of what we know about the climate?

here’s a stigma around some of these practices, but there doesn’t need to be. If we can tell a positive story about them, we can make them replicable, scalable, and mainstream. We can’t just be tinkering at the edges if we want to have a better society. We need a mindset shift. I think positive examples motivate a lot more than just highlighting the problems. We do need to keep a grip on reality. But if we can find the things that work and scale them up, that’s really positive.

-

You’ve written about the importance of including women’s perspectives in your work. What is the importance of gender equity to Remade’s mission, and how does this play out in practice?

To be honest, it’s something I find really frustrating because I think women’s agency is still incredibly devalued. I find it depressing that in the 21st century, we’ve still got these battles to fight around the perception of women. There’s a really interesting parallel with the whole repair world—now that it’s become sexy and popular, it’s men who are really taking the credit and getting celebrated for it. As Remade has grown as a business, it’s been men who’ve wanted to take it over. When I’ve tried to speak vocally about it, I’ve been shot down and called a huge egotist.

I think a feminist perspective is not just the struggle against patriarchy. It’s about a creative perspective that puts care, not money, at the center of the economy. We know that women’s work in the home is often unvalued, yet that work is essential. Maybe we can begin to see that the everyday act of looking after people and things, of repair and mending, is also quite radical. It would be nice to think that as we talk more publicly about repair culture, we value the people who aren’t just suddenly saying, “Oh, this is a great new idea,” but rather the people who’ve always been doing that work, sometimes without being seen.

“The term ‘community’ can be used in quite a tokenistic way. What does it really mean? It means people, local people. What’s happening in each community is going to be different, so what are their concerns? What are their needs?”

This interview is part of “Circular Views”, an editorial series produced in collaboration with subscription-based furnishing company NORNORM. Spotlighting innovative thinkers, each interview explores a different dimension of circularity with the goal of raising awareness and fostering a creatively driven movement rooted in circular practices. Watch the trailer here.

Sophie Unwin is the founder of Remade Network, a Glasgow-based grassroots network and social enterprise dedicated to amplifying repair culture and putting it in the service of people and the planet. Remade’s projects range from affordable repair services to mending classes, all the way to desktop distribution projects designed to tackle digital inclusion. Want to get involved or simply find out more? Explore Remade’s program or follow Remade on Instagram.

Along with Sophie Unwin, this series features NORNORM founder Anders Jepsen and industrial designer Stefan Diez. To learn more about circularity, be sure to also read our Link List #164: Fostering our literacy on circularity.

NORNORM is a subscription-based furnishing model on a mission to define the future of how we work. NORNORM’s objective and vision is to apply a circular model to office interiors—and therefore promote the well-being of both employees, businesses, and the planet—by providing flexible, affordable, and inspiring work environments through using, and reusing, resources intelligently.

Interview: Anna Dorothea Ker

Photography: Antony Sojka