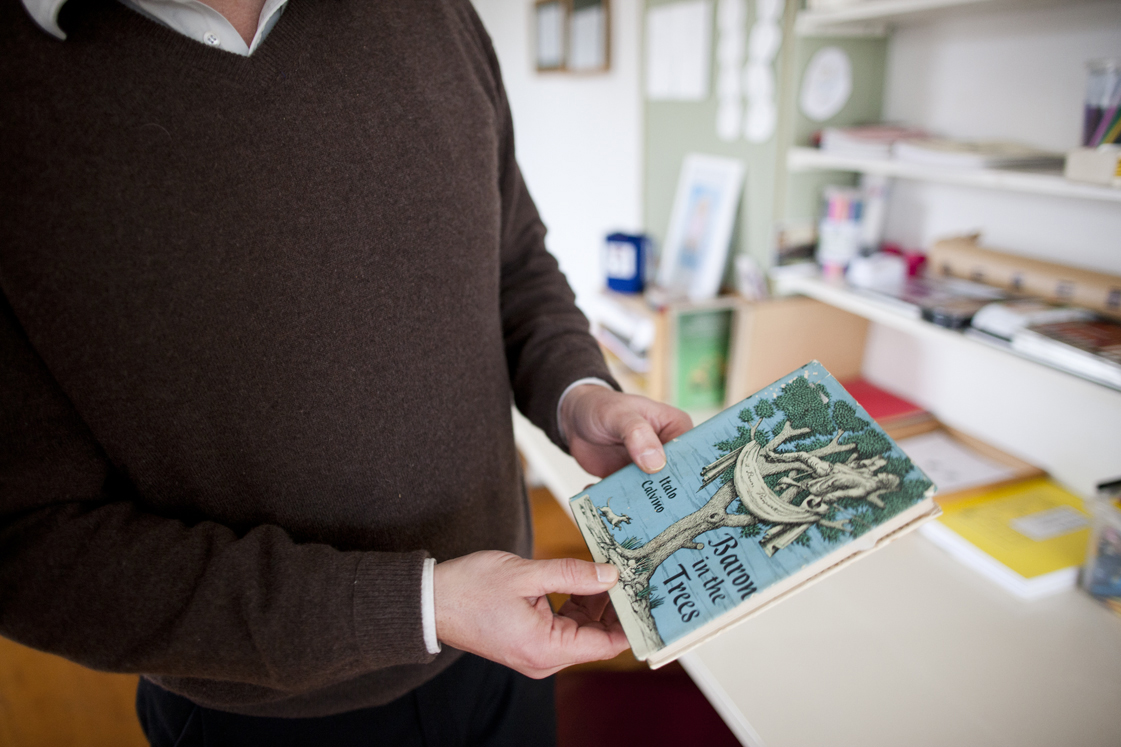

A poet held in captivity by the advertisement industry for years, is what Lorenzo de Rita considers himself to be. After a fierce struggle with the conservative advertisement standards, De Rita set himself free, and started The Soon Institute. A playground, a mental space, focused on experimenting new models of thinking and the development of what he calls “prototypes for communication.”

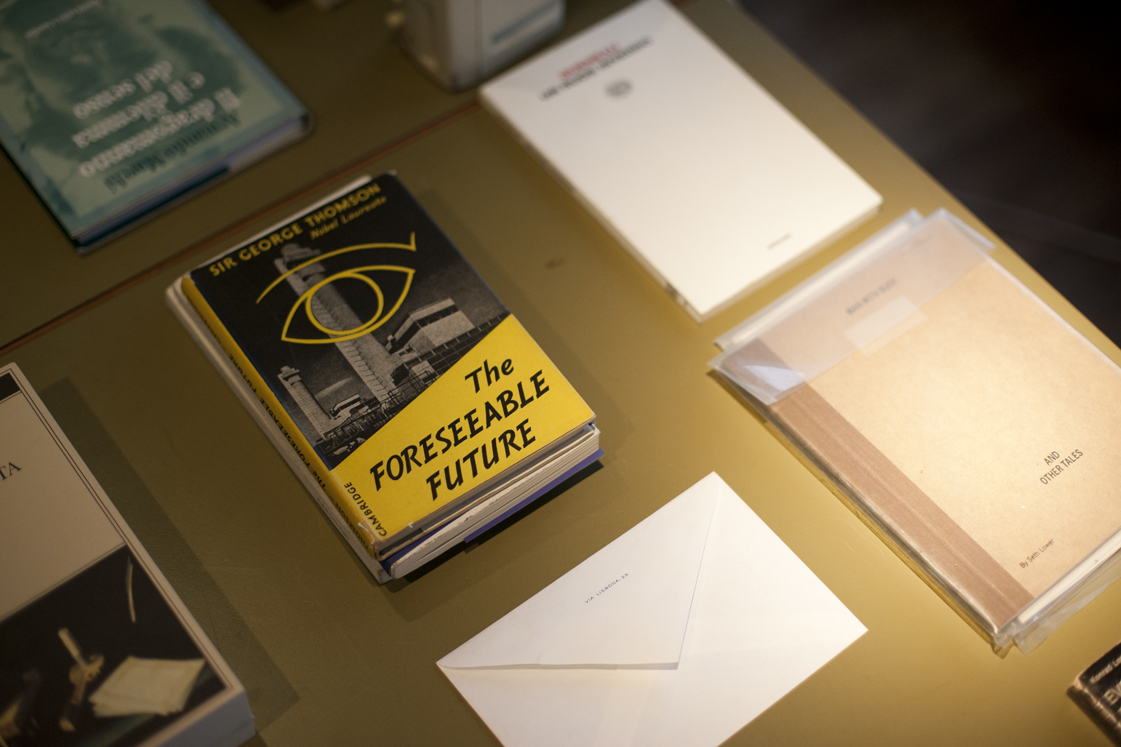

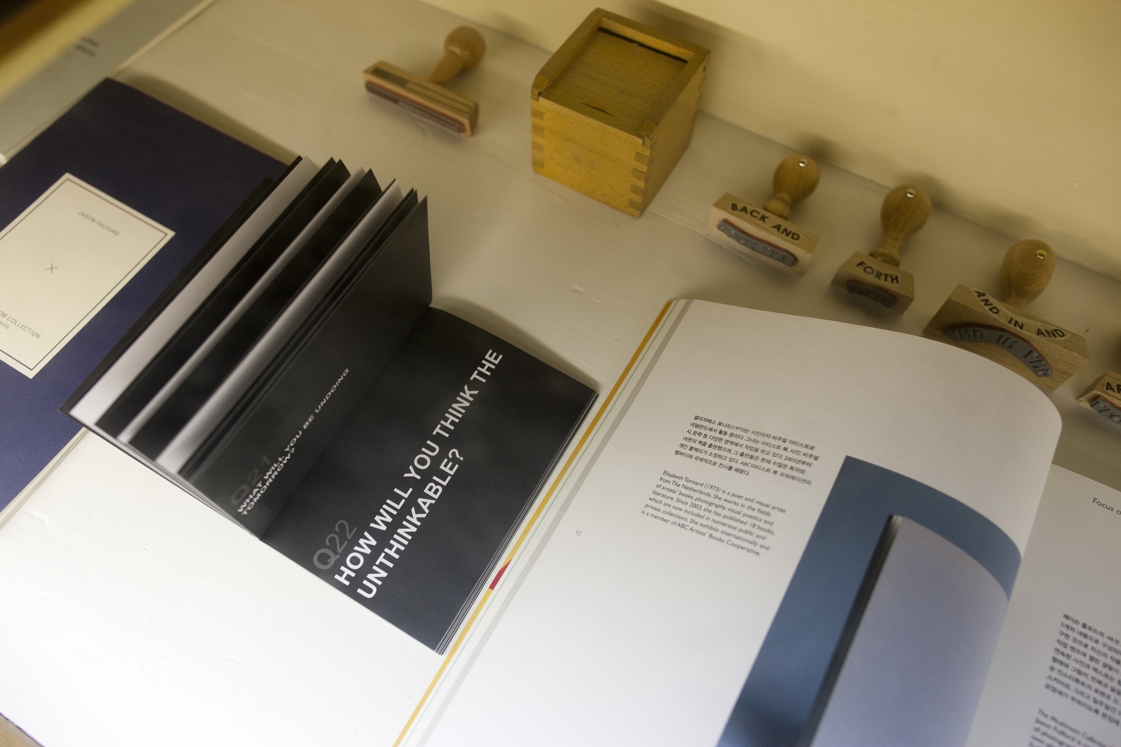

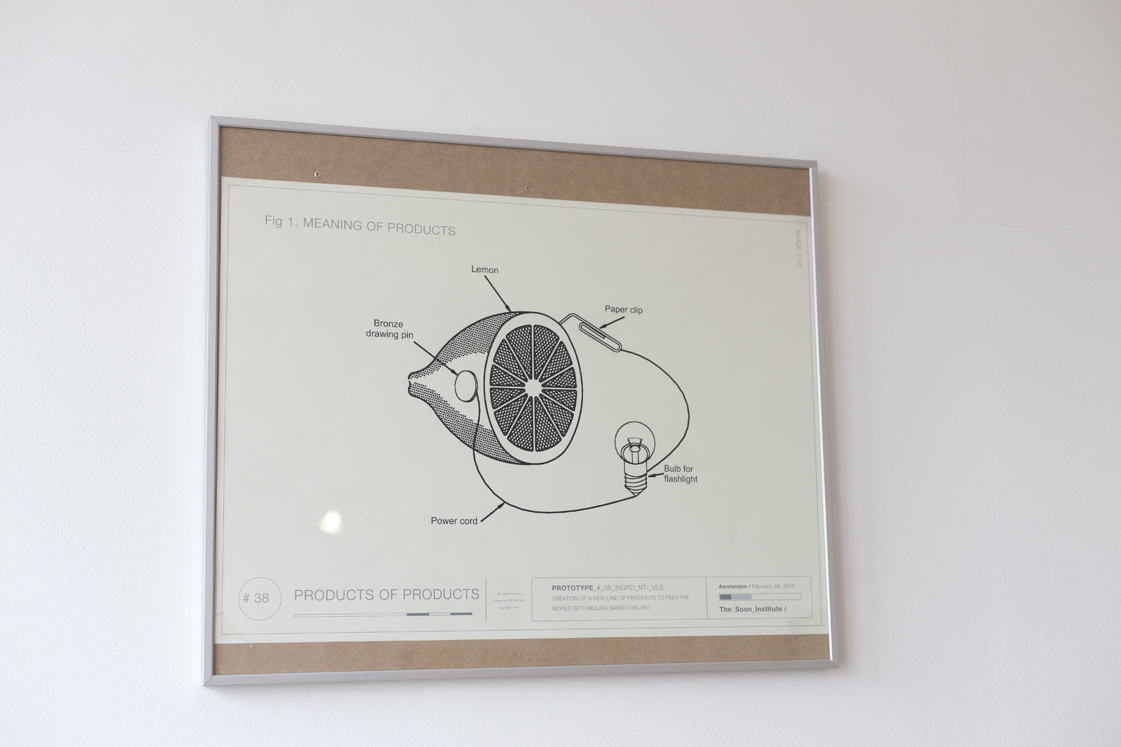

Seemingly unrestrained by practical or commercial limitations, The Soon Institute developed some 57 prototypes in just three years. A navigation system for your kitchen is in development and the world’s longest water pipeline is under construction. Besides prototypes, The Soon Institute publishes a variety of daring books that challenge the readers in really reading the book in any sense.

His studio in a former school building at Museumplein in Amsterdam, as well as his impressive house overlooking the Amstel river that drags you into De Rita’s world, and most importantly one full of inspiring ideas and unexpected ways of thinking. Welcome to a world that is not yet there.

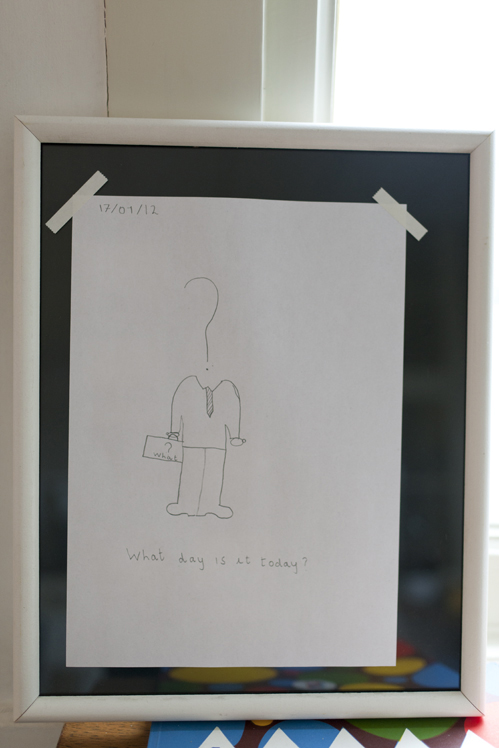

What is The Soon Institute?

Hmm, I am struggling with associating the Institute to a… what. Definitions risk constraining it (The Soon Institute) into something finished, complete, and boxed. Yet already from the name one can tell it is something unfinished, unclear, unpredictable; voluntarily un-thought to a degree. Let’s say it is a point of view, a different way of looking at things: not for what they actually are, but for what they could or should be. We explore possibilities and when we find an interesting one, we develop it into a prototype, a model for the forthcoming society.

Where does your interest in new ways of thinking and communicating come from?

I have a background in advertising and worked for a number of renowned firms, for companies such as Nike, Adidas, Diesel and Volvo. However, I never felt comfortable with the advertising business. I started by writing poetry, and when they proposed me to write ads I thought it made sense: it was still about writing. But that was stupid, I entered a cage. It was a semantic trap, for twenty years I was completely schizophrenic: doing something I profoundly disliked.

It sounds like you were quite successful though.

I wondered myself why that was, I only found a decent answer recently. I think the more you dislike something, then the less you accept the way it is. That somehow forces you to make that something better. So my creativity was finding a ground in the non-acceptance of the existing, and so by refusing to become someone else from whom I thought I was – a poet.

You are originally from Italy. Was it the advertising business that brought you to Amsterdam?

Yes it was. I am from Rome and grew up in a typical Italian family, one out of eight children and catholic. Multitude and a sense of guilt are two things that have always influenced the way I lived and work. After years of advertising in Rome and Milan I was offered a job at Wieden+Kennedy in Amsterdam, working for Nike. I did not want to go, but no one else wanted to, and so I accepted the job offer. After a couple of years I moved on to the firm 180, working as a global creative director for Adidas. But I felt more and more tired of the business; of the cage. No matter how poetic and different the things I was doing were, it was not poetic and different enough. So I tried to escape to start my own project. However, being responsible for your kids make you think twice, and having four kids made me think twice more. A job at KesselsKramer followed, after which I worked at Fuel for a short while. In hindsight these were just sidesteps.

The final switch came with an offer from the Italian pasta producers- Barilla. They came with an offer that was hard to refuse, it was with an enormity of money, but I declined. The boss of Barilla could not believe I refused his offer, and sent an employee to figure out what it was I wanted. So I told him, then henceforth I started The Soon Institute.

Barilla helped you out financially?

Yes, they commissioned us the first twenty prototypes of The Soon Institute.

How many prototypes did you develop since The Soon Institute started three years ago?

We are working on number 57 currently, a travel agency for mind travelers.

Do some prototypes also turn into actual products?

Definitely, jointhepipe.org is one example. We designed water bottles that resemble units of a common water pipe. They are made out of reusable plastic and can be connected one with another. Every member that joins the pipe receives a bottle. The project saves the consumption of thousands of plastic water bottles, and the income is used for the development of wells in developing nations. The idea is that the more people join, the longer the pipe will become and so less people on the other side of the world will die of thirst.

A navigation system that is orientated towards the world of cooking is another project that is reaching maturity. Currently we are also testing a machine that is able to turn Internet into a physical place, a clock that tells the quality of time, and also we are opening a museum that has only one square meter.

Can you describe how The Soon Institute works? How are prototypes developed?

It is based on the process used in the car industry to build cars, for example: the product you sell becomes the direct consequence of the experience of building a prototype of that product. I was doing a project for Volvo once and visited their prototype laboratory. Truly an amazing place, where people try out all different kinds of ideas without necessarily having a direct focus of this application itself. I was surprised to find a terrarium with frogs there. Volvo engineers used them for inspiration.

You need a playground to create new things, develop new ideas. The advertising business provides exactly the opposite. Its framework, concepts, and jargon date back to the 1950s. It is completely conservative.

My approach can best be described as phosphorescent thinking as opposed to incandescent thinking.

Phosphorescent thinking?

With incandescent lighting you just turn the switch and you have light. It is like Coca-Cola: you open the bottle, drink, and burp then trash the bottle and feel to drink again. There is no time for thinking there. With phosphorescent lighting it is the other way around: first light is absorbed, and when it turns dark light is emitted. The absorption process give you time to look at various aspects, and also allowing you to focus on details. The new needs time, attention, more than fantasy to be revealed.

You also publish books.

Well they are books; they require an effort from the reader. They are fairly difficult to consume.

What are they about? Can you give me an example?

Our latest book is called Pasquale Demichele. The author of the book is Alberto De Michele, an Italian/Dutch artist who just came out of the Rijkscademie van Beeldede Kunsten in Amsterdam. Last year Alberto was shooting a documentary on a criminal gang operating in the North of Italy, where his father Pasquale is a member.

After finishing the documentary it turned out the Italian police had been watching all along. They had tapped the phones, took photos, and arrested Pasquale.

We used the dossier with all the transcripts of phone calls, indictments, and hearing reports to create the book. But we altered the contents of the dossier by selectively canceling sentences and names using Tipp-Ex correction fluid. So you could tell it is a book written by canceling it.

Do the books relate to the prototypes you create?

They are also part of the playground. Just as the prototypes they can be considered experiments – challenges to the readers.

The products are not necessarily something people consume?

Many people are motivated by desire, which results in consumption. Desire also eliminates our ability to believe. Belief has been replaced by cynicism. This is problematic because without the belief it is hard to advance. With The Soon Institute, I aim to provide tools that help people revive their beliefs.

Would you consider it a failure if the society and projects you visualize do not materialize?

No. I always thought it is better to lose as a poet than to win as an engineer.

To see & hear more about Lorenzo de Rita and The Soon Institute you can visit their website for more inspiration.

Photos: Jordi Huisman

Text: Thijs van Velzen