Henry Hargreaves lives in a 1930s brick building that, like many others in its vicinity, was once a factory.

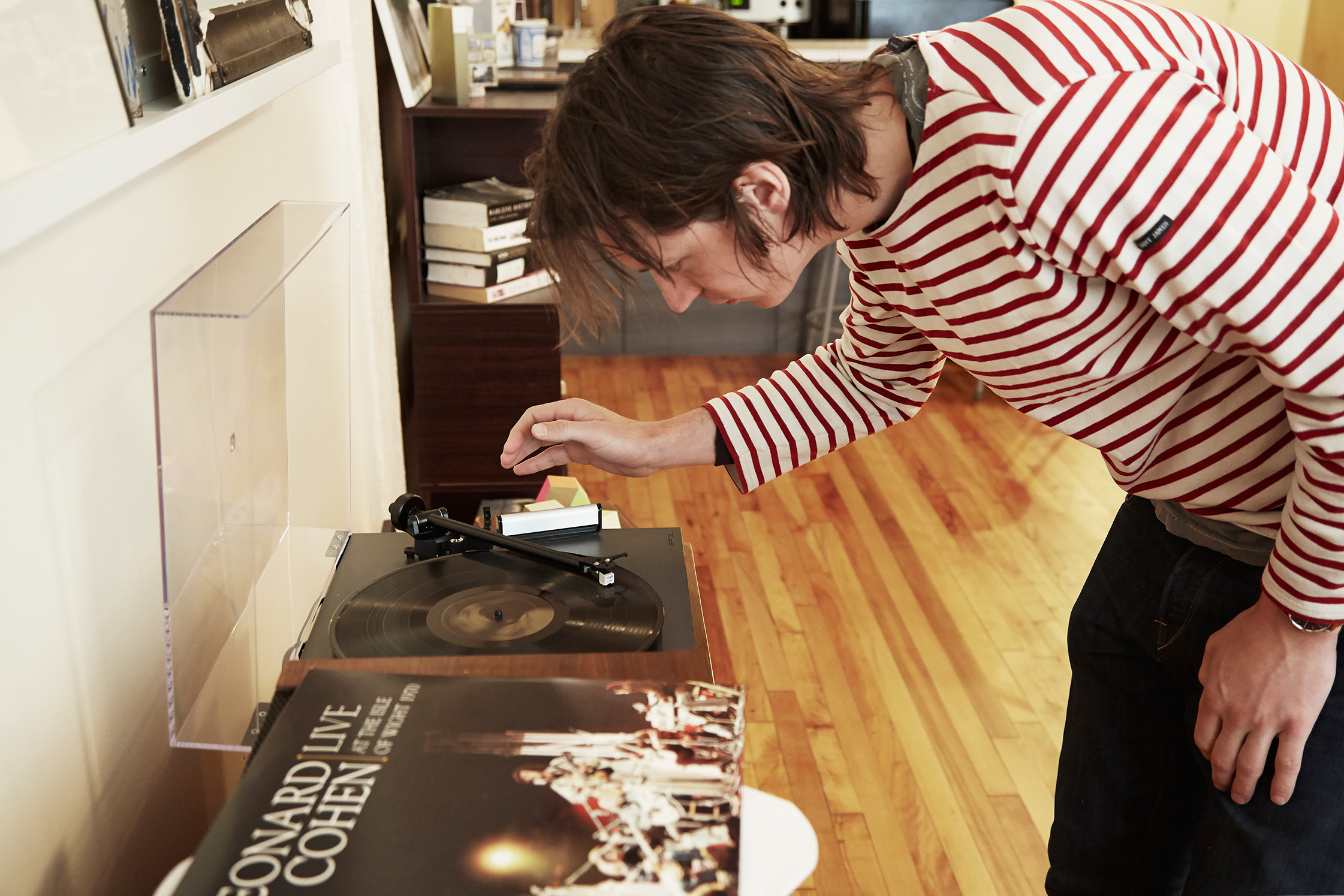

His apartment, three stories up, contains a hallmark or two of Brooklyn living: a projector stands in for a television screen; a record player takes center stage atop a wooden credenza. On the day of our interview, a friend gently chides that his refrigerator is a stereotypical bachelor’s, almost empty except for salad dressing, hummus, and the takeout tucked away in the subterrane of the bottom shelf.

But that’s where the familiar tune ends.

Henry, a native New Zealander, has lived in this city ten years, a length of time many agree officially awards one the title of “New Yorker.” Over the course of that decade, he’s transitioned from fashion model to photographer, building a body of work focused largely on image-based storytelling through food. It’s work that’s allowed him the pretext to perform such experiments as setting fire to cake, deep frying iPhones, and reconstructing the Louvre in gingerbread and licorice. It’s also afforded him the insight to speak on the impact of food on our awareness of others (as he did this March for TEDxManhattan). “I like showing people everyday things in ways that might surprise them,” he says.

“People are born in a city like London and stay ‘til they die – in New York, people come, but most of them leave once they’ve burnt out. That’s part of what gives it its energy, I think: that everyone wants to do their thing – and do it well – while they’re here.”

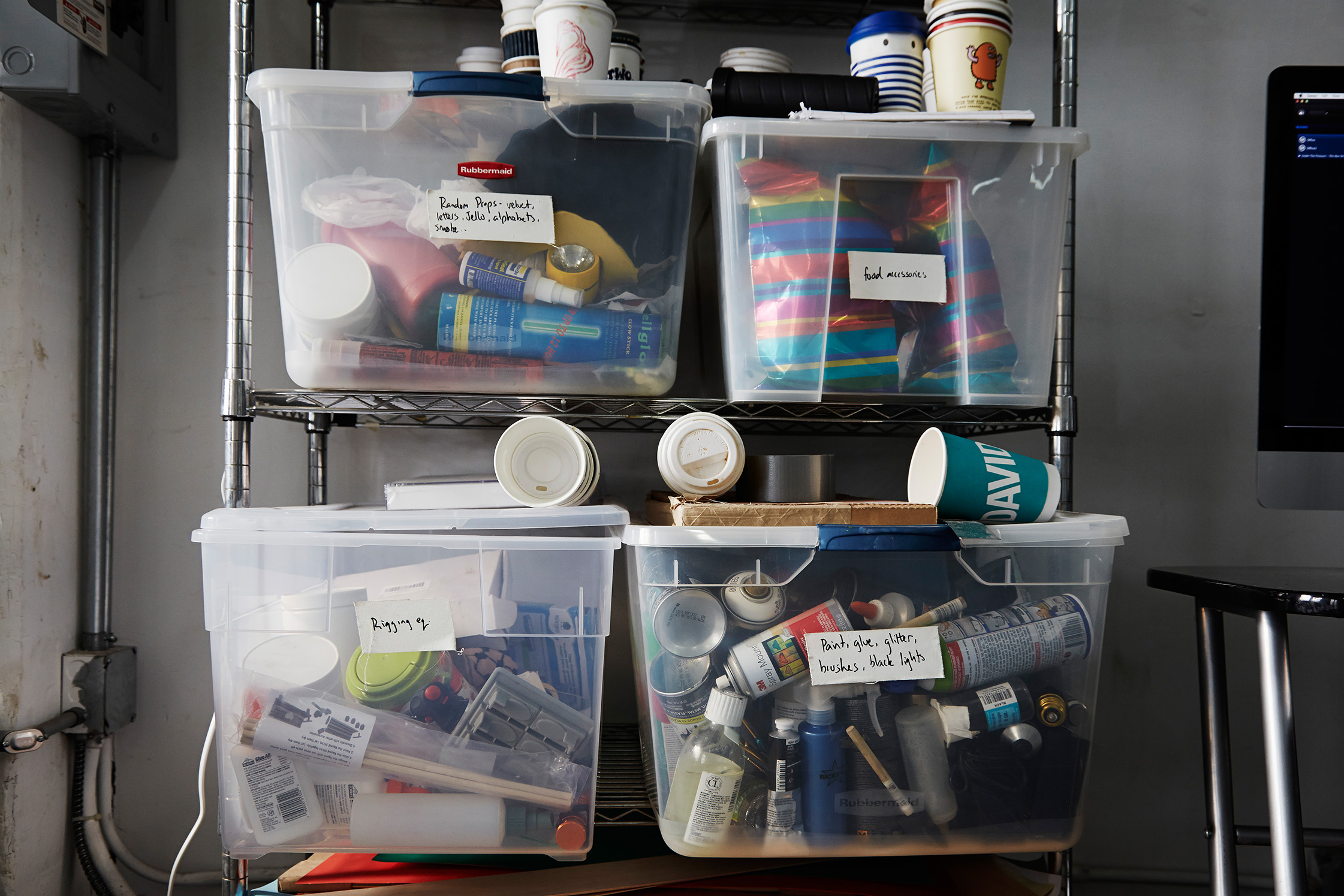

Much of this work takes shape ten minutes from his apartment, at a Bushwick studio whose towering windows and vast expanse of blue-gray flooring are – to the eyes of anyone accustomed to the city’s narrow confines – a surprise in and of themselves. In the corner sits a cluster of boxes, full of materials for an upcoming project on the meals of doomsday preppers. There’s a ladder propped against the wall nearby, alongside tubes and poles and slabs of wood. Things here are in a state of constant change, Henry notes. New things in, old things out. “That’s a process,” he says, “that doesn’t end.”

This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who present a special curation of our pictures on ZEIT Magazin Online.

-

You’ve spoken in the past about how an early career as a model led you to your current work as a photographer. Has photography always been a passion, or was that an interest that developed over time?

I’ve always been interested in images. But photography hadn’t ever occurred to me as a career possibility – growing up in New Zealand, I didn’t know there was any such thing as a successful photographer. If anyone was able to do it, it was as a teacher or the guy who took your picture in school. It wasn’t until I got involved in fashion that I realized this world existed and that I’d rather be the one taking the pictures than standing in front of the camera. So the next step was: how do I make that happen?

-

What did the process of making that switch entail?

I started taking pictures. I bought a camera and began shooting the other models. It’s a funny thing: in the modeling world, everyone talks about what they do – no one’s just a model. Everyone’s an actor or a director or a writer on the side, but not everyone actually does those things. I decided that if I was going to call myself a photographer, then I was going to really follow through.

In the beginning, I figured that knowing people in the fashion world would open a few doors. But when I moved to New York and got a job bartending at Schiller’s on the Lower East Side, I found that way more opportunities came from networking with customers. That’s really how it all began. Then, as I slowly realized I wasn’t interested in fashion, I started moving toward other things.

-

Since then some of your most popular work – a series depicting the last meals of death row inmates, or regional delicacies arranged into the shapes of their native countries, for example – has involved food. Why?

I realized that I didn’t have a unique point of view when it came to fashion – I wasn’t able to do anything that no one else could do there. So I decided I’d do still life. The first few jobs I was getting were frustrating because I was finding that I couldn’t do the shoots by myself. I was relying on stylists to help, and cost was an issue. That’s when I realized that the cheapest supply store was the supermarket. I thought, I’ll just do everything here.And since I can’t cook apart from avocado on toast, I thought I’d use the food to tell stories.

-

As an artist who works with food, do you think the fact that you don’t cook works in your favor or against you?

Maybe I’m justifying my laziness, but think it separates me from other people who do what I do. To me, food still exists in this magical realm that I have no control over, so I have somewhat of a different perception of it.

Food is interesting because it can act as a common denominator between you as a viewer and a subject you’ve got nothing in common with – you may be different, but because you understand food, you understand something about them. You don’t need much else.

-

You mentioned using food as a storytelling device – how do you decide which stories to tell? Where do your ideas come from?

I love looking at blogs, but I don’t look at ones that focus specifically on photography because I don’t want to get caught up in, I wish I’d done that. I find I’m more likely to get ideas from sites like This Isn’t Happiness or Things Organized Neatly. I’ll see something and think, that would be fun to turn on its head or to make out of food. I also pay attention to current events – I’ll read a news story and think about how to represent it visually. That’s how the series on last meals, “No Seconds,” came about.

“I love discovering new music. I like being able to buy records and get to know them – I don’t want to put something on that I already know. I’m at my least creative when I’m listening to things I’m familiar with inside and out – if my brain can predict the music, I fall into the same creative patterns. But if I can’t predict it, I see things in different ways.”

-

That series, like several you’ve done, went viral. Is there a secret to producing material that catches on in that way, or is it accidental?

Early on, I did a silly series with Star Wars characters after a snowstorm, and it went viral. Suddenly, I was getting offers from all over the place, and I wondered whether I should just be trying to create projects that would get spoken about. Jessica Walsh says something interesting about that, which is, “If you do what you love, the money will follow.” There’s real truth in that. I realized I should just concentrate on what I want to be doing, and the work would follow from there.

I’ve also learned not to pay so much attention to how something might be received. That’s one of my strengths: I’ve got a book of ideas and I’m good at making them happen. I figure, if it sucks, it sucks. Some of the most exciting things come of situations where it’s a disaster or it just doesn’t work out – that’s where the fun stuff happens.

-

Do you have a favorite project, of the many you’ve done?

I don’t see value in what I’ve done; I see value in what I’m going to do next. I don’t really look back too often. In terms of things that I’m particularly proud of, though – they’re projects I was never sure I was going to be able to pull off from the start. The gingerbread art galleries, for instance, was a concept Caitlin Levin and I sold to Dylan Lauren, and we’d never even had gingerbread. We didn’t know what it was like. So it was all about experimenting. It took a week of building and labor to make all of those pieces – and it was really cool stumbling on an end result we hadn’t expected.

-

Last year you launched a blog called Coffee Cups of the World, which is a visual index of noteworthy paper coffee cups. Tell us about how that began.

I got a coffee at The Smile one day and realized later that I didn’t want to throw away the cup. It had a beautiful stamp on it, and I felt like I really got my money’s worth – it was art. From there, I began to wonder whether you could tell the quality of the coffee by the cup it came in, and I found that, to a certain extent, you could. There’s often a correlation between the amount of time that goes into creating the cup itself and the time that goes into making the coffee. I thought, what if I focus on what people are doing on the cups and try to encourage that practice?

It’s also a great narrative to follow as I travel. So often, you’re aimless in a new city. I’ll go to this museum or that gallery, but now I’m also going to all of these interesting cafes and I’m exploring new places that way. It’s a fun way to work.

“I love the ritual of coffee. I love having a cup and being able to nurse it – and I love how cheap it is.”

-

It must be a fun way to explore your own city, too. What drew you to New York in the first place?

I spent some time traveling in Asia after school and was based in Europe during my modeling years, but I found that of all the cities I’d been, New York felt the most positive. People are born in a city like London and stay ‘til they die. In New York, people come, but most of them leave once they’ve burnt out. That’s part of what gives it its energy, I think. Everyone wants to do their thing – and do it well – while they’re here. I really responded to that, and I wanted to stay. I’ve been here now for ten years.

-

And how long have you lived and worked in Bushwick?

I’ve had my studio in this building for ten years, and I’ve lived in my apartment six months.

“Food is interesting because it can act as a common denominator between you as a viewer and a subject you’ve got nothing in common with – you may be different, but because you understand food, you understand something about them.”

-

Is any of the artwork on display in your home your own?

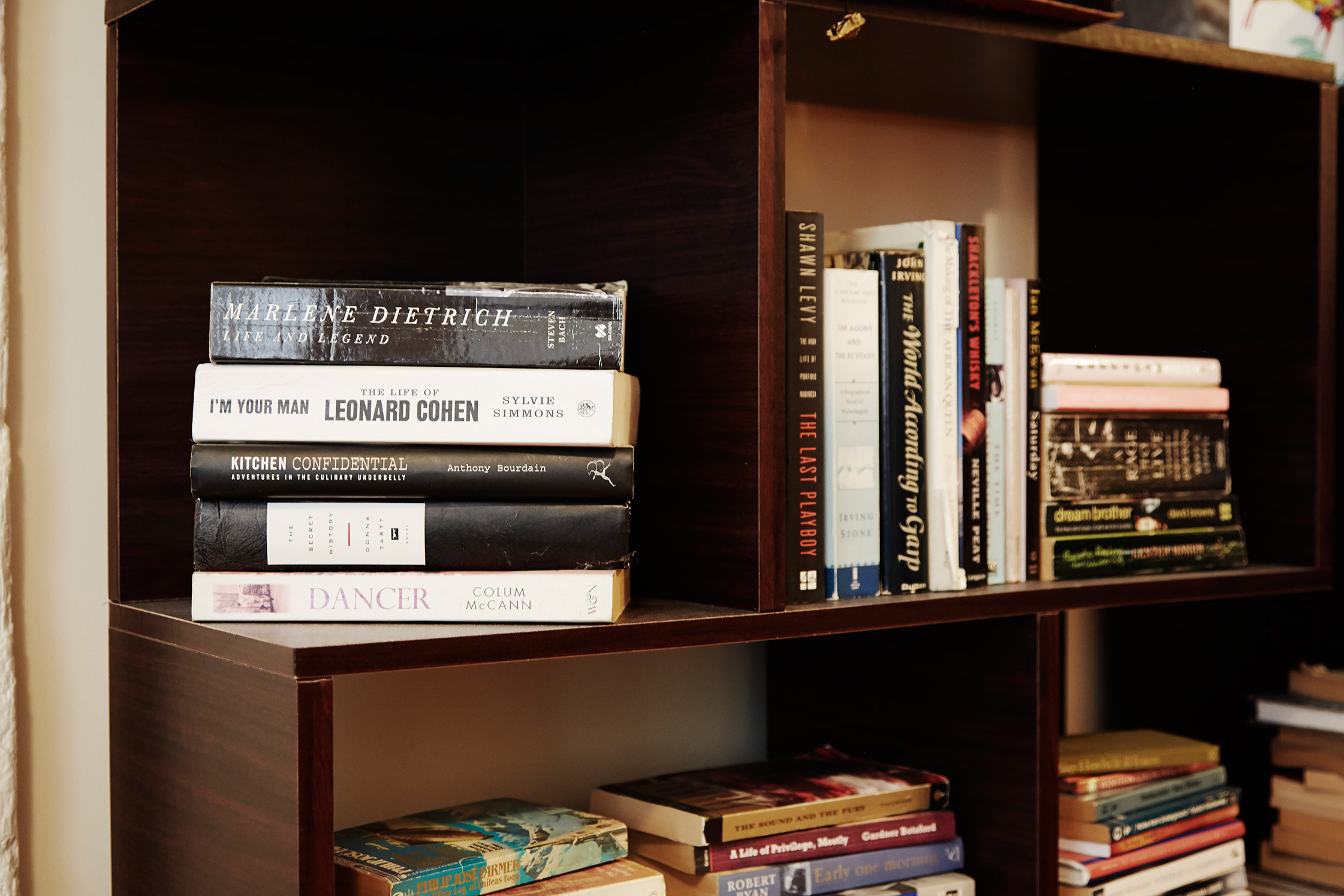

I don’t like to put my own stuff up, but everything here’s got a story behind it. A lot of it comes from people I know. The wooden ark on top of the bookcase was bartered with a friend, Oliver Clegg; there are some pencil drawings done by my cousin’s wife. My great-grandfather was one of the first New Zealand photographers, and he did a whole series on the Maori – there’s one of those, and some nice cards I’ve gotten over time, and a photo of mum on her wedding day.

Then there’s art that I’ve collected over time: a couple of things by famous New Zealand artists; photographs by Edward Steichen; a Space Oddity hologram from the gift shop at the David Bowie exhibition in Chicago. I have a photograph in the kitchen by Raphaël Dallaporta, whose stuff I found online and fell in love with. I had to send a friend of mine to Paris with 900 Euros in cash to get it. He pulled up at an intersection on a motorbike, gave him the tube, and they went their separate ways. The photo’s part of his series on organs in great churches around Paris.

-

To ask a bit of a clichéd question: what would you save in a fire?

Anything that someone spent time making. Mum made me a photo album for my 30th birthday, and she also made the blanket that goes on my bed. I have artwork from friends, prints they’ve given me. Anything that someone chose for me thinking, this would be good for you – it’s those kinds of things that money can’t replace. So I’d save those – and my hard drive.

Learn more about Henry Hargreaves on his website.

Photography: Brandon Schulman

Interview & Text: Shoko Wanger