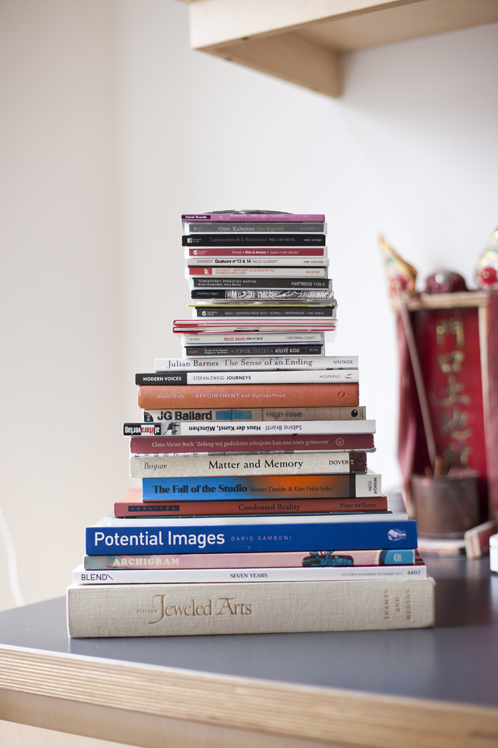

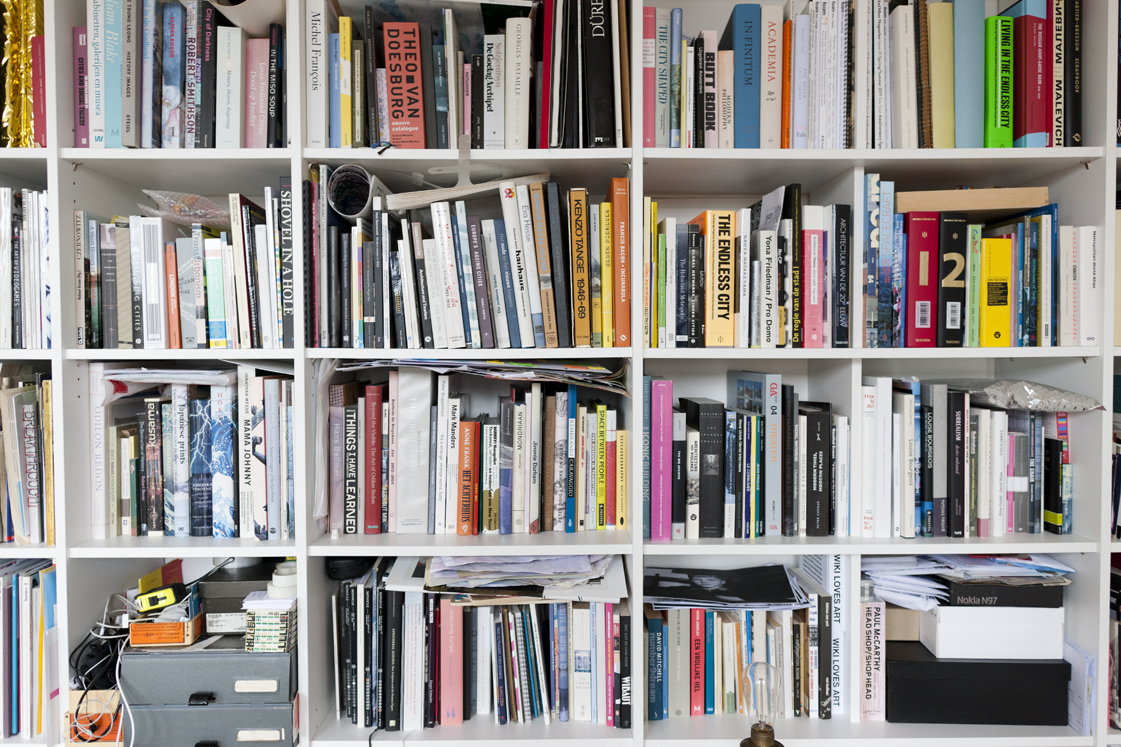

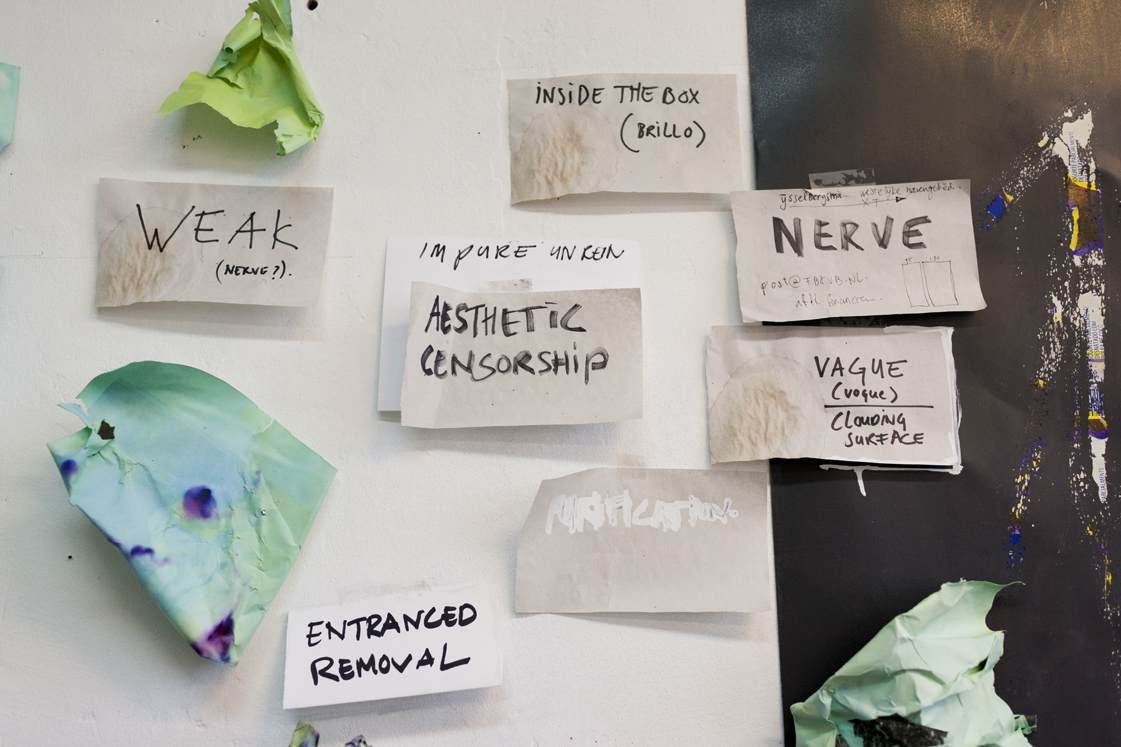

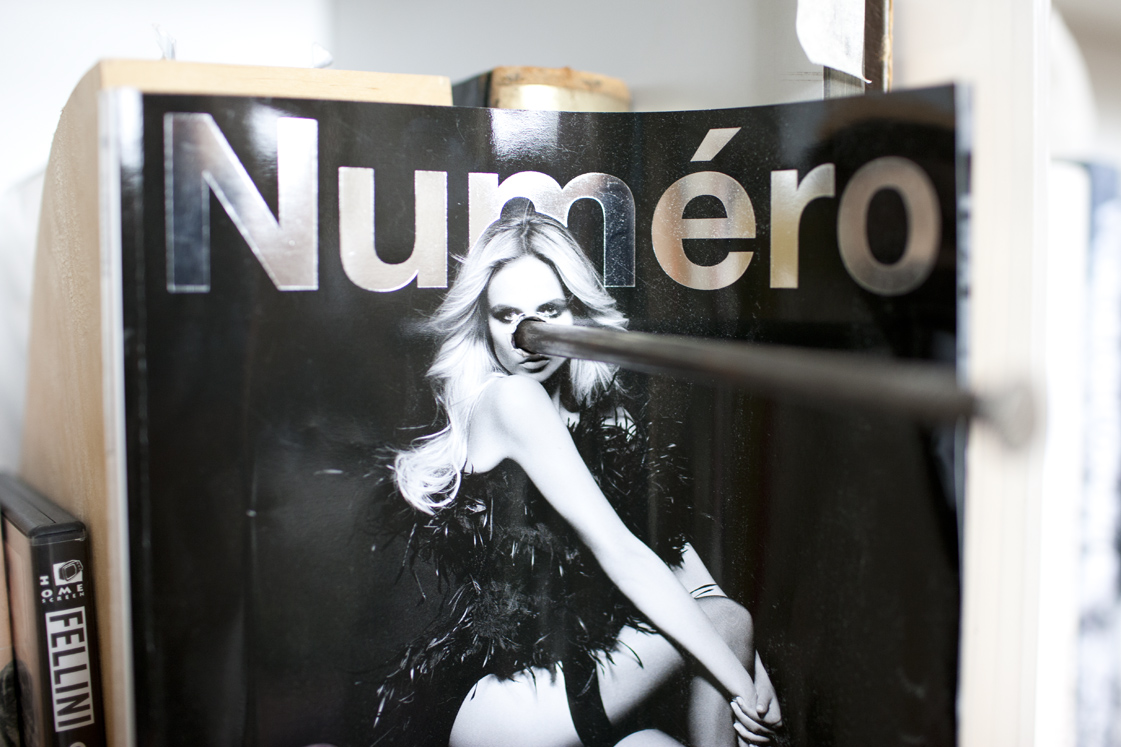

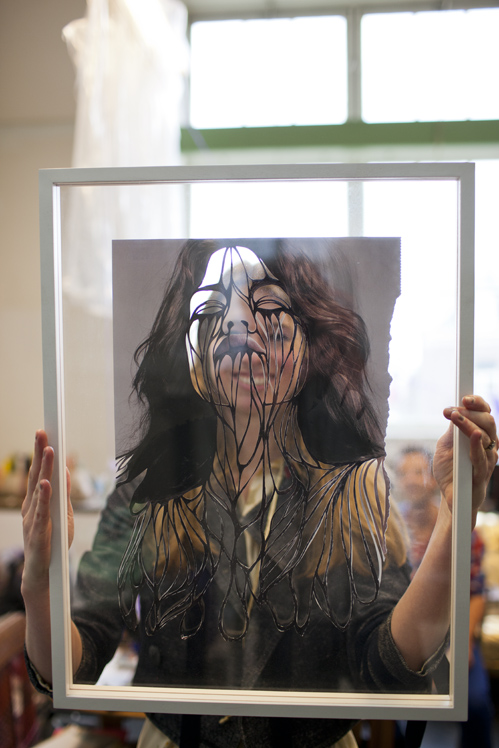

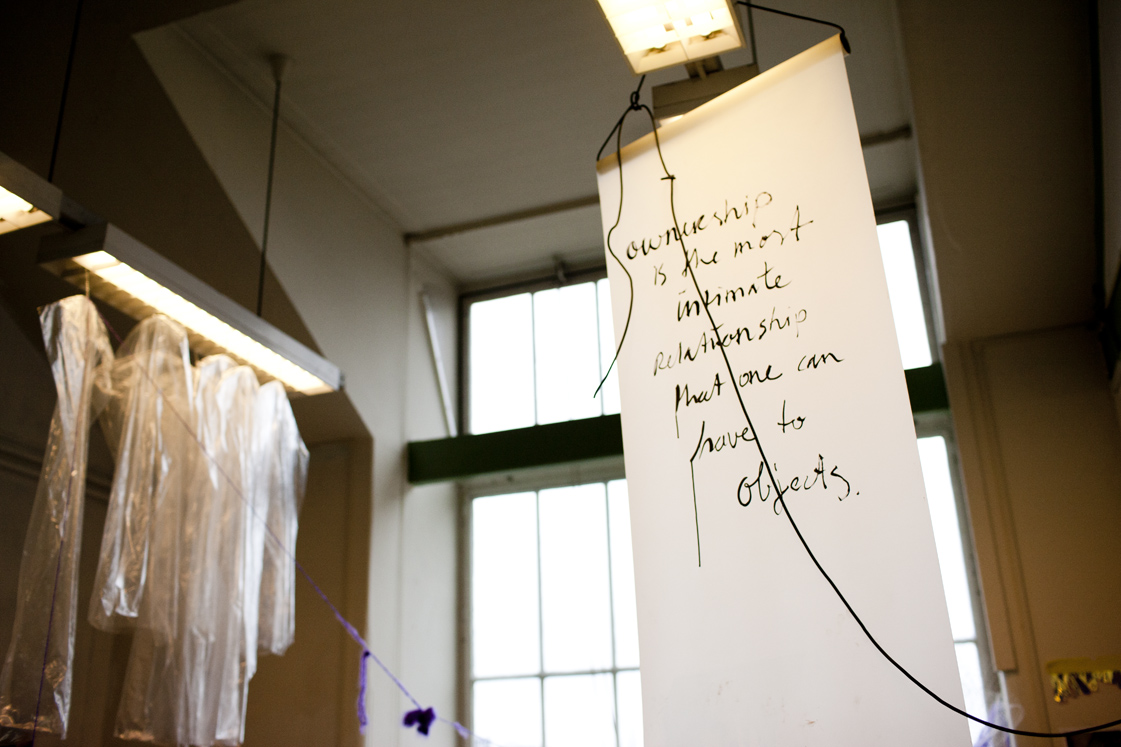

Amie Dicke is done with cutting and altering fashion magazines, the works for which she is best known. Although cuttings and nail-pierced magazines can still be found in abundance at her studio, they now share her cluttered studio with wrapped furniture, objects covered in foundation, water tanks filled with colour prints, and a fur coat stashed in glass closet.

The contrast with her apartment can hardly be greater. Tidy versus chaotic; the two spaces almost look like a metaphor for Amie’s current work, in which she explores the interaction between physical space, objects, their history, and people.

Although busily working on an important solo exhibition planned for coming autumn and preparing a road tour for a chair from a former World War II hideout, the Amsterdam based artist still finds the time for an extensive Friday afternoon conversation, explaining to us how the history of the city is inching its way into her work.

This Portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who present a special curation of our pictures on their site. Have a look here!

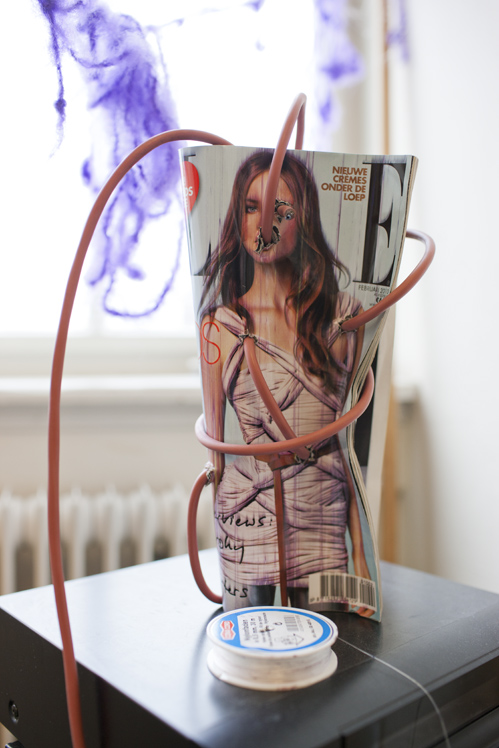

Fashion magazines proved to be useful material in your work. Selectively cutting fashion photos, driving nails through entire magazines. How should I interpret these works?

The cuttings started while I was living in New York City for a year. I moved there in 2001, after finishing the Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam for my then-boyfriend. New York is overwhelming. The pace. Its assertive inhabitants. And its enormous billboards. These impressive advertisements became some sort of anchor points for me. I used them for orientation, and they made me feel familiar with the city. At the same time the billboards embodied the aspects of NY that I dislike: the never ending rush, and especially the focus on commerciality. I started dissecting fashion photos as a way of reflection. In this way the photos became personal, and a part of myself.

There is also a hint of mutilation. Can your work be read as a rejection of the commercial industry or rejection of the ideal of beauty?

Partly, maybe. But it is also an expression of the attraction it has on me. I can find the fashion industry and the ideal of beauty disturbing, but sometimes cannot resist the urge to buy a fashion magazine. Hate love. I once banned magazines, but found myself buying one a little later. It is like an addiction and like any addiction it is difficult to quit. The balance between fascination and frustration provides inspiration.

Was New York important in itself?

My time in New York was of great importance to me. I moved there just after finishing art academy, and left everything familiar behind. It was really a coming-of-age story. New York was a great school. I experienced the American mentality, and found useful elements in it. The way Americans present themselves is one example. People always come up with an interesting, daring, and catching story, whereas artists in Europe or the Netherlands tend to be more retained.

Is your success also related to your time in New York?

After I moved back the works I developed in New York received positive reviews. Galerie Diana Stigter showed interest in my work and hosted an exhibition. The cuttings were very successful indeed. But after a while I started to find them appalling, making them made me unhappy. In a way the works started consuming me. At some point I could not make cuttings any longer and decided I had to move on.

Was there a specific reason or event that made you stop creating cuttings?

I don’t think so. I was just done with it. Criticizing the fashion industry is also fairly easy. I was ready for more daring projects. For the final cutting I used a photo of myself, and that was it.

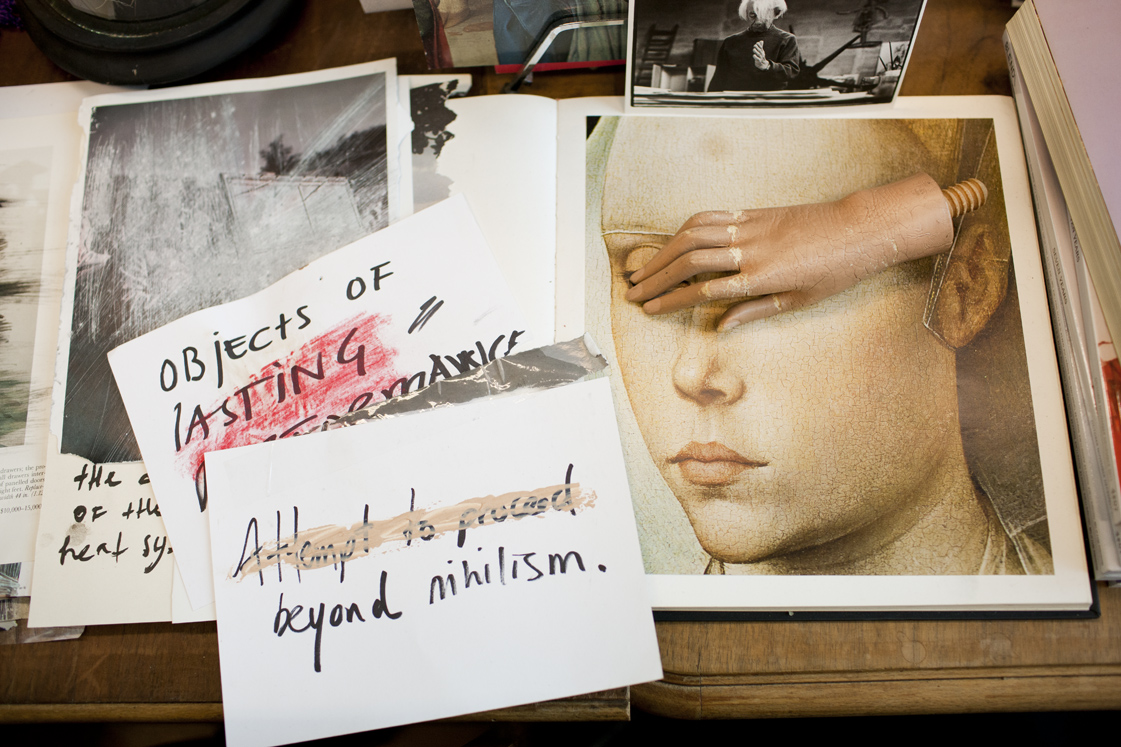

What are the questions that were occupying you the most as an art student? Did they change a lot until today?

Towards the end of my studying years at the art academy in Rotterdam, I started to become very aware of this moment you have to present yourself for the first time to the public. After learning so much about art, art history and all the artists- my predecessors and certainly hero’s- it is suddenly your turn. I became very conscious of that position and was asking myself the question: Where do I stand after all this. Taking this question literally, I created a stand for myself. I made a pressing of my legs from crotch to foot in marzipan coated with icing. The soft substance echoed the negative curves of my body. The sculpture was smoothly molded and resulted in conical pillar of sugar. Standing astride, luxuriating in the sugary substance of honey-like transparency that slides down its thighs.

The sculpture was entitled How sweet is the space between my legs. This was my first sculpture. I realized I liked this position. It was very close to the skin and revealed a lot, but at the same time I was absent. Visible and invisible together. That sculpture proved to be more fragile than I expected it to be. I was promised that it would probably last for several years by the baker who helped me prepare this project. But as soon as they were finished the marzipan surface started to split and fall apart. Apparently, decay is a process to which my sculpture was prone. In a state of constant deterioration, through sagging and cracking. The discovery of these deformities provided me with a whole new perspective: the un-containable beauty. Perhaps it’s the certainty of decay that makes beauty so appealing. My attempt to position myself permanently proved to be an illusion. The sculpture of the space between my legs is now nothing but a memory. I still have the tendency to create a visible and or invisible space within a magazine page or in a interior, a place where I can insert my questions.

Can you name something challenging you have been working on since?

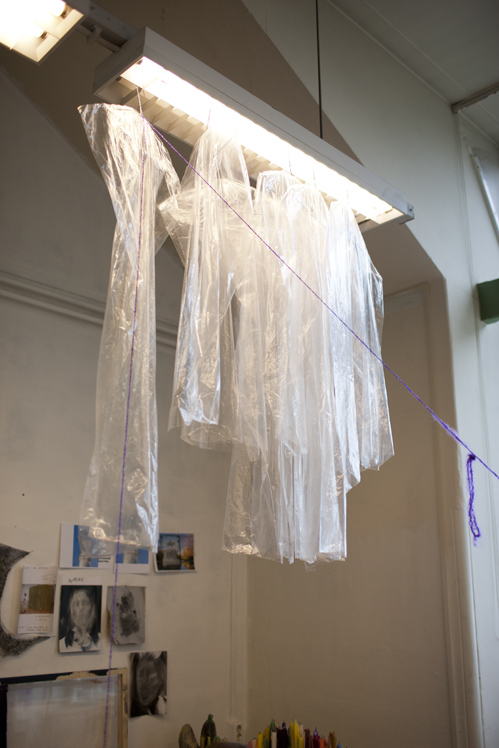

The installation I did at Castrum Peregrini was definitely interesting. Castrum was a safe house for group of men during World War II. The apartment they shared has hardly changed since. The men developed a very special bond during the war years, and wrote poems, made paintings. Some of them stayed after the war. Today the Castrum’s building functions as a cultural centre for debate, and is nowadays run by three men. What’s more, the patroness, who turns hundred this year, still occupies the top floor and has her apartment at the attic. The intimate bond and almost mythical aura is still present today. After one of the original inhabitants passed away, it was decided that his apartment needed a clean up. But at the same time everyone would have loved to keep it untouched. I thought that this could be the best test of aura, what remains when the interior is removed. And in that room I created an installation. I covered everything in transparent plastic and tape, after which the furniture was removed piece by piece. In the end only the plastic cover shaped by the objects and interior pieces remained, like a death mask of the room.

Why was this project challenging?

Castrum has such an impressive and private history. It is a place that commands respect. You can’t go in there and tear something apart. There a numerous layers, and stories of many people. It has many dimensions, which makes Castrum much more complex than the fashion industry.

The work you made at Castrum Peregrini was highly contextual. Has context gained importance in your recent work?

The history of a place has gained importance. The impact of past events on the way we perceive a place in the present is fascinating. Through my work I try to explore this effect. Interior plays an important role. I am currently considering a project at the Hilles House in England. I have got in to contact with Detmar Blow, the grandson of the architect and original owner of the place. This beautiful house also has a long history. And I slowly start to unravel more and more of the intriguing family history. It is really like an opera. But also has terrible stories to tell: two family members, among who Detmar’s wife Isabella Blow, committed suicide here.

Do physical surroundings also influence you personally?

Definitely. Rotterdam, where I was born and raised, shaped me for a great deal. About six years ago, after New York and some time in Berlin, I moved to Amsterdam. Compared to Rotterdam, which was nearly erased in the 1940 bombings, the city has much more ‘visible’ history. Amsterdam is slowly finding its way into my life and my work.

Do you think it is particulary hard to live and work as an artist today compared to bygone decades?

I do not think it is harder today. I think it has been the same and will be. It will always be difficult and wonderful. Maybe women today, like myself, have even more choices and a certain freedom to become an autonomous artist.

Did you have an alternative option to becoming an artist?

No. Maybe art started for me when I was walking to elementary school and back home every day. During these walks I would find leaves, stones and all kinds of objects that not only seemed beautiful to me but almost personalities on their own. Also things you can not grasp, like one day when I saw the sun shining on a quite insignificant brick wall I wanted to imprint this image into my memory to not let it be lost. And it worked, I still remember it, although that image of the sun on that brick wall is less pretty to me now. I think it was more about the insight, but then I really thought it was that image. Later I understood that these sensitivities can be discovered more and kept in the arts.

What do you like most about Amsterdam? What are your favorite spots in the city?

Amsterdam is a small city but has a lot to offer. I live near the Zoo Hortus Botanicus and Artis, and with my membership card I can go in and out daily. The Portuguese synagoge is a beautiful place to visit, although I bike more past it. By bike I ride to my studio and cross the Magere Brug, a thin bridge over the Amstel, almost daily. This is always a wonderful spot. My favorite bar is Cafe Krom because of it’s atmosphere and good service. They have a jukebox which still runs on the 10 cents from before the euro was introduced, so you just ask for the money at the bar and then you can select the music. At the horrible Rembrandt square, Cafe Schiller is also quite an amazing oasis. Then Trouw at the Wibautstraat has a great restaurant and reminds me a bit of Rotterdam. In the winter I love to bike along the canals and smell the fire places and look inside the houses. From my window I can see the Mill ‘De Gooyer’ and it houses the brewery ‘t IJ. The beer is very tasty and a lovely place to visit in the summer.

What place would really like to visit in the nearer future?

I actually want to see the first meter that was created that must be somewhere in Paris. When my daughter is one meter and she almost is, we will visit.

Thank you Amie!

Find more of her work on her website

Photography: Jordi Huisman

Text: Thijs van Velzen