Amidst the sprawling urban metropolis of concrete and skyscrapers, Bangkok can be a surprising city with moments of calm, of colorful local chaos, and of green oasis.

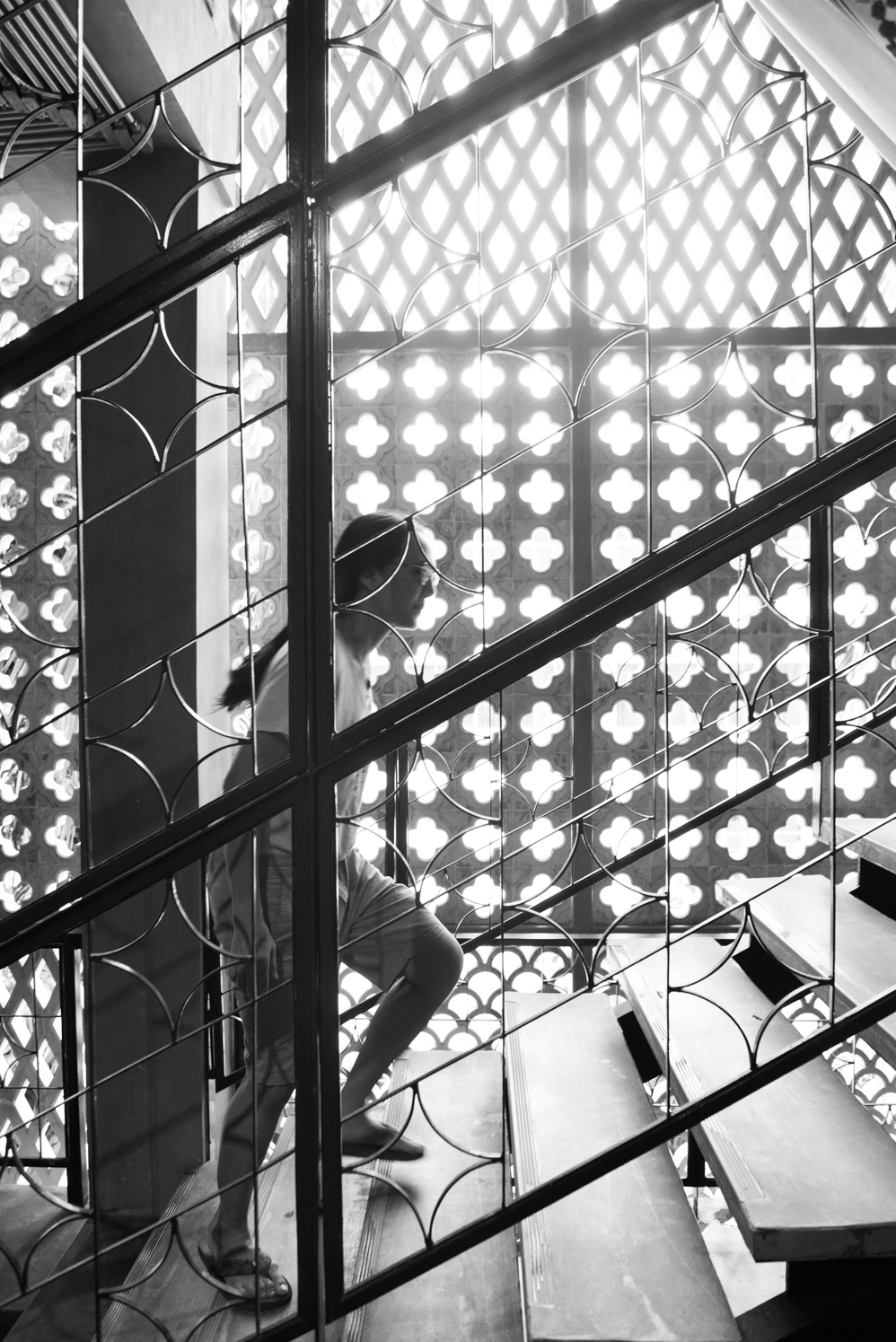

Ing Kanjanavanit’s Cinema Oasis could not be more apt a name for what it is. Tucked away in an alley on Sukhumvit Road, the building, with its minimalist form but elaborate facade, welcomes you into a space that stands at stark contrast to its immediate environment—one that thrives on commerciality. The house used to belong to Ing’s family; she grew up in the Sukhumvit district when it was still orchards and small roads. Today, it’s home to the non-profit cinema and art space, repurposed to promote neglected and oppressed films, and to inspire filmmakers and other artists to openly talk about freedom of expression and issues such as the role of cultural colonialism, deep history, and propaganda.

Ing started her career as an investigative journalist, concerned with the impact of unheeded tourism, AIDS, and human rights abuse in Thailand. Frustrated with restrictions posed on writers she turned to filmmaking, believing that real footage does not lie. Being a filmmaker in her country, however, doesn’t come with less challenges: Ing’s first fictional film, the experimental feature My Teacher Eats Biscuits, was banned—the government considers it an insult to all religions. The 2008 documentary, Citizen Juling, about a teacher in Southern Thailand who was murdered in the midst of extremist violence that engulfed the region, won her numerous awards; her following project, Shakespeare Must Die, an adaptation of William Shakespeare’s Macbeth is also banned, seen as “a national security threat.”

-

Will you show Shakespeare Must Die at Cinema Oasis?

The film has been in jail for six years. Everything is allowed on the internet but films can be jailed forever, though it has been screened in Lebanon and Paris last year.

If the Berlinale had not rejected it, it would’ve been in the same year as Caesar Must Die! Unfortunately, the Berlinale thinks I’m some kind of Thai Leni Riefenstahl after they showed my Southern Unrest film Citizen Juling in 2009 and pro-Thaksin (Thai Trump-Duterte-Hun Sen) Western academics staged a hate campaign against it. This is probably why there is no other film directly on the Thai Southern Unrest and the war on drugs despite thousands of deaths and missing persons, because any factual, truthful film on these issues would inevitably make Thaksin look bad—other Thai filmmakers do not want my fate.

-

Have you taken any actions to change that?

We sued the Film Censorship Board in the administrative court, which tries power abuses. We lost in the first court and filed an appeal, which is being considered in the Supreme Administrative Court.

-

With the case still pending, where has your energy been focused?

During the censorship process I kept following my producer, Manit Sriwanichpoom, around with a camera and I ended up with another film called Censor Must Die. The censors made this historic ruling for Censor Must Die, citing the Film Act clause 27.1 that “films made from events that really happened” are exempt from censorship. That was an historic ruling: It freed up all the documentaries that were made from real events; no propaganda, just cut, cut, cut.

But then they said we had no permission to film them (the subjects of the film!) in their office and threatened to sue any cinema that would release the film. As long as you have the film banning law there is fear—everyone is afraid—and we aren’t officially able to show our films.

“As long as you have the film banning law there is fear—everyone is afraid—and we aren’t officially able to show our films.”

-

But Cinema Oasis still does.

It’s a refuge for people with the same predicament. If you have something to say and you are good there is at least one place for you. All the cinemas in this country are owned by something like three people, and those people are also the studios. It’s like an anti-trust law that is broken beyond, but who is going to fight it as long as there is this film banning law?

-

What happens when you show your films there?

I’ve tested the ruling with the first part of Bangkok Joyride and we got away with it. Then I played part two and three. The censors have not come calling. We’ve played other Southeast Asian documentaries as well with no problems so far.

-

What is Bangkok Joyride about?

I filmed some crowds during the [anti-government] protests in 2013 to use the material for another movie and realized that there was nothing normal about it. Something felt so free and natural and pure about these people who were getting over their fear of death.

-

Can you describe the scene?

They were living their lives in the open for seven months. It was uniquely cinematic. You have to be sensitive though. I shot one woman who was living under a transparent pink mosquito net and who put a potted plant into her tent to make it seem like her garden. And there she was brushing her hair, whether there was tear gas or not, or whatever. I shot her from the back—a little creepy but, I mean, she was in the street and I had the right to shoot her—and it was really moving. I didn’t have to see her face. Bangkok Joyride became full of moments like that.

-

In 2017, the King, Rama IX, died. Have you documented the event’s impact?

Yes, on a blog, as a moment of transition. I was a best-selling writer but I have no more space to do that. It’s the same with many other experienced journalists who care about facts; no more print space for them either.

-

Since when?

I think it changed in 1998, that was the year we lost our battle to save a sacred island national park from being re-landscaped with bulldozers for Danny Boyle’s movie The Beach owned by 20th Century Fox, which is owned by the Murdoch media empire. The way they used the media to obliterate Thai environmentalists was unbelievable. This coincided with the rise of the internet. I realized then that a new day has dawned when facts and the truth mean nothing. We were on the frontline and the first victims, but this is standard media practice now. The whole democracy machine is being undermined by subversion of social discourse.

-

So what did you do?

I switched to filmmaking because no one believed my investigative reports on the environment. I was one of the first to write about the evils of tourism; for me, it’s the real-estate industry and hotels that are destroying national parks. Even when I said that AIDS is fatal they accused me of starting a panic, of scaremongering. Hard to believe now, right? I had to fight for each piece and it was so tiring, so I started shooting—that allows you to take people with you.

-

How do you depict what you witness today?

My family witnessed the forbidden history so we know the injustice of distortion. For me it’s enough to be a witness in this life, that’s all I do. That’s what these films are about and it’s just chronological editing. When people saw part two [of Bangkok Joyride] in a test screening, and there was a scene with an angry woman yelling at police officers, they asked: why didn’t you put that as a climax at the end? I can’t do that because it happened at the beginning. It’s the sequence in which it happened chronologically.

“My family witnessed the forbidden history so we know the injustice of distortion. For me it’s enough to be a witness in this life, that’s all I do.”

-

Were your films more metaphorical before?

This one is based on facts but it’s still subjective; it’s my lens. With Shakespeare Must Die I wanted to express emotions.

-

And so you switched to fiction?

Yes, because I thought it would be freeing. My Teacher Eats Biscuits was banned as an insult to all religions. It’s set in an ashram where people worship a dog. It’s a comedy, because I was sick of people feeling angry after seeing my documentaries; I wanted to do something fun.

With fiction I’m used to writing to the edge of the cliff, to the very edge of what is allowed. I forget that with a script it’s only the beginning. Once you have the footage and see people in pink gowns worshipping this dog, saying ‘dog god’ in front of an animal, it’s so much more potent than lines on a page. Therefore, I can see how the censors felt so freaked out by it. When I saw it again, in Paris, that was quite hardcore. -

It’s funny, no?

It’s very black humor. It’s satire, that’s what Likay [Thai folk opera] is about: They go around villages and ask for gossip to incorporate it into their performances. We are like sponges, we absorb what’s happening.

A selection of films from director Ing K

All the movies played at Cinema Oasis are apocalyptic. One thing that really scares me is social media, though: how they can hack, manipulate, and make people feel like the whole world is a high-school popularity contest. It’s not so much fake news; I reckon you can’t stop people from saying hate speech and fake news because then you would censor everyone. There is this scene in Shakespeare Must Die, with Goddess Durga, during which all the school kids come in and sing to the dear leader, as if in a trance. That’s scary.

Bangkok-based filmmaker Ing K is the founder of Cinema Oasis, dedicated to showcasing works in a a space where oppressed and overlooked movies are shown.. Her portfolio counts fictional stories, such as Shakespeare Must Die and My Teacher Eats Biscuits, and real-life documentaries.

Text: Chom Weeraworawit

Photography: Jason Lang