The prolific artist Judy Darragh and Grant Major, the Oscar-winning production designer behind The Lord of the Rings on arts education and working the ranks in creative fields.

Judy Darragh and Grant Major have lived together in their three-level modernist house in Auckland, New Zealand, for the past eighteen years. During that time, the house has seen the couple and their 21-year-old son Buster through multiple art-show openings, school projects, home-studio renovations, and industry parties. The shag-pile carpet and ceiling rosettes have long since been removed from the home’s interior, but the spirit of family remains: found inside their kitchen cupboard doors are height markers spanning several decades.

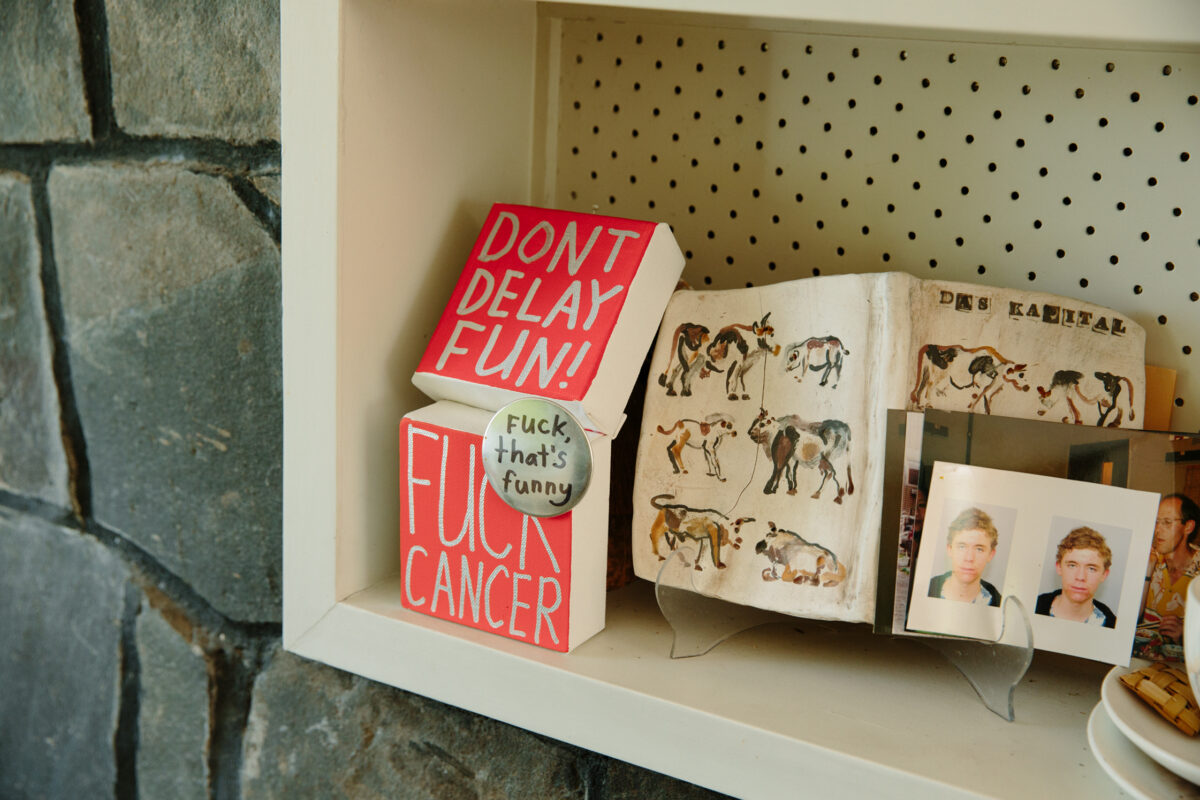

As one might imagine, Major and Darragh’s interiors are a visual extension of both of their creative minds and lifestyles. “It’s history through object, everything has a story,” explains Darragh. Traded art, props from film sets, and kitsch or found objects bulge from their shelves. “The rule is: if it’s a bargain, get it,” she claims of her maximalist displays.

As an artist who explores large-scale sculpture through found and recycled objects, Darragh’s endeavours have gained her the title ‘Queen of Kitsch.’ Her love for art stemmed from childhood, growing up on the South Island of New Zealand in Christchurch. Her mother she describes as “a maker, industrious, and unafraid of hard labor” and a father who worked for the freezing works and was in the labor union: “They would go on strike at every opportunity, so there were always a lot of socialist and political discussions at home,” she adds. “In high school, I had two amazing art teachers, they were different to the other teachers, and I identified with them,” she explains.

Coming from what Darragh considers to be “a conservative Christchurch” they were a breath of fresh air. It is, perhaps, this combination of fearless discipline from her mother, her father’s example of standing up for what you believe in, and the courage to exist outside of conventional norms as influenced by her art teachers, that makes Darragh who she is today—a maker, a collaborator, and someone who enjoys other artists’ dialogue. “I enjoy working with artists’ collectives, the autonomy is liberating. I feel lucky to be an artist.”

“There is no genius.”

Grant Major

Seeking out environments that allow for discourse with other artists is vital to Darragh’s practice. For the third time she will attend a residency at the Montalvo Arts Center in Saratoga, California, for a three-month stint with the Lucas residency program. This time, Major will accompany her. The residency experience will be a first time for him, and a welcome interlude between one long-time project finishing and the next starting.

“You arrive and there is just a table and a chair,” Darragh explains of the center, followed by a look of mock despair. “I am so used to having many materials around me, so this was a huge shock to my creative system. But I have come to appreciate a blank space, and have since adopted this approach at other times,” she adds. “Although, there’s nothing wrong with a bit of mess,” adds Major. “It opens opportunities for things to be paired that wouldn’t have been otherwise.”

“It was weird being thrust into the fast lane of my profession quite abruptly and unprepared.” (Grant Major)

Major talks about his own experience as “incremental, one thing leading to the next.” Receiving a Diploma in Graphic Design from ATI (now AUT), Major gained his “fine art experience” on the local sets at TVNZ and other various film sets until he found himself leading a team for one of the biggest films in cinematic history, The Lord of The Rings. A pivotal project for Major’s career, The LOTR trilogy resulted in a run of international accolades for the artist, including an Oscar for his work in LOTR: The Return of The King (2004). The following year, Major was bestowed the New Zealand Order of Merit for his services to the New Zealand film industry. “Things were never the same after that,” he exclaims. “It was weird being thrust into the fast lane of my profession quite abruptly and unprepared. It took another seven-to-eight years to get over the speed wobbles and to feel at home there.”

Major gained a reputation overseas that would see him flying to a different location around the world every two-to-three weeks, on average, for 18 months—a grueling schedule that was both exhilarating and exhausting. “People even called me ‘Sir’!” But, he claims he is still practicing what he started way back in 1976, which is “crawling, slaving, and shoving my way to becoming a film production designer.”

A similar trajectory applies to Darragh, who also trained as a graphic designer, but who taught her way through her tertiary studies. She explains, “We were given $90-a-week to teach as we studied, it was great money back then, and we were the last generation able to be free of student-loan debt because of it.”

“As a senior artist I feel responsible for addressing issues surrounding the underrepresentation of female artists in institutions, awards and collections.”

Judy Darragh

But becoming an artist “was an intuitive passion,” Darragh claims, which she followed through “until I could write ‘artist’ as my occupation on the departure card you fill in when you leave the country.” Other events significantly altered the course of her career: Having a child “definitely put the art world into perspective for me, and I’ve never used time so well as since then.” And Darragh’s retrospective exhibition, ‘So, You Made It?’, curated by Natasha Conland at New Zealand’s national museum, Te Papa, was a huge opportunity for the artist to view her past works in overview and context, offering both direction and reflection.

For Major, reflections of his own success are credited to “all the talented and influential people that have carried me to amazing creative places.” But essentially, Grant believes success comes down to consistent, hard work, “and enjoying your work so that it becomes a way of life.”

In a similar vein, making art and teaching art have been interwoven in Judy’s life; she has taught art at secondary and tertiary levels for 40 years. However, nowadays, the artist aims to avoid any university establishments. “I don’t want to support this neo-liberalist approach that is currently inherent in our arts’ educational system. I mean, firstly, getting rid of your library is not a good look,” says Judy, commenting on the Elam School of Fine Arts’ recent decision to discard their entire library in order to downsize and cut budgets, which she describes as a devastating loss to both the school and the local arts’ community. “They’re trying to stuff an arts education into a box that it does not fit. It all comes down to numbers and wages; many jobs were lost in that exercise, both librarians and teachers. Their logic is: Why would we have one tutor speak to a room of 12 when we can jam 400 students into a lecture hall. They think it’s the same thing, but it is not.”

“I don’t want to support this neo-liberalist approach that is currently inherent in our arts’ educational system.”

Judy Darragh

Even with her significant roles in the development of local artistic initiatives, and with works displayed in public art galleries and museums, such as her dazzling meteorite-like forms for Limbo installed at the Auckland Art Gallery, Darragh tells me there are still many frustrations for artists here in New Zealand, especially female, and they are yet to be truly heard or represented. “I am still having the same conversations with my 80-year-old writer friend as I am with a painter who is 30 years my junior. As a more experienced artist I feel responsible for addressing issues surrounding the underrepresentation of female artists in institutions, awards, and collections.” She continues, “for example, The Designers Institute of New Zealand awards two black pins per annum, its supreme award. The Best Design Awards over the past 20 years have awarded 43 black pins: 40 to men, three to women.” Judy’s face is overcome with a look of weary shock.

Because of her social conscience, there is inevitably a political undercurrent to Darragh’s artwork. In line with this, as well as delivering on her artistic commitments she is also working to create a manifesto for the government, suggesting how they should set up structures to facilitate artists’ copyright and artists’ royalties on secondary sell-ons, all in favor of the artist. “The manifesto will be our collective voice speaking upon matters that immediately affect us. We have never been spoken to directly; it is always those ‘above’ us who have been consulted. That needs to change.” Judy is at her most serious when she says, “When they get to us [the artists], and they [the government] will, we want to be ready.”

Find out more About Judy Darragh’s call to action to New Zealand artists and learn more about Grant Major’s work. More people from the creative fields talk about their background, inspiration and work in our interviews section.

Text: Yasmine Ganley

Photography: Greta van der Star