Rolling hills, vast fields, secluded lakes, rustic farmhouses, and quaint farm shops selling local produce. A description of Brandenburg’s Uckermark region easily reads like a romanticized travel cliché.

A popular enclave among Berlin creatives, the rural region about an hour northeast of the capital attracts urban dwellers seeking tranquility. Set against sprawling lawns, photographer Stefan Heinrich’s project Kleines Haus in Flieth is hence no rare occurrence; over the course of two years, he has reconstructed a century-old barn into an open-plan living space surrounded by towering grass and oak trees. In Flieth he is part of a close-knit community; his next-door neighbors, Horst und Gaby, have called the unassuming village home for almost fifty years.

Heinrichs’ outside dining table is a smorgasbord of local treats: freshly baked bread, cheeses, cured ham, ripe tomatoes, and boiled eggs are served alongside homegrown grapes and berries from shrubs planted all over the premises. His residence serves few reminders of his commercial background—the agency he works for is based in London, a city he never felt the urge to call home. “This is where I open up and let my guard down. I’m 100% in my element. The distractions you have here rather support you or help you advance; gardening, listening to music, and reading all clears my head,” Heinrichs says about his new-found joy in a streamlined lifestyle. “You broaden your mindset,” he continues, rephrasing Günter Grass. “It’s about discovering something new, but in a simple way.” Here in Flieth, his ease and relaxation are almost palpable, feelings that he ascribes to a journey he embarked on without longing for it. Only in hindsight he is able to grasp his need for a change of scenery.

Heinrich’s career has been smooth. After studying photography and assisting international photographers, his transition to becoming an independent photographer soon followed. “When I worked as an assistant, I was given a lot of responsibility, which has helped me learn to trust myself and follow my instincts,” he says. Today, Heinrich’s portfolio covers decade-long work for internationally renowned fashion magazines, such as Vogue, and reflects his deep interest in the human being. Mainly centered around the studio in the beginning, he gradually moved out of this comfort zone, particularly by taking his subjects outside. “I’m at this point where I recognize that there has always been a guiding force behind my work. I always set goals for myself but there was a lot of external influence,” he says.

“It’s about discovering something new, but in a simple way.”

For Heinrichs, fashion is “a framework that can support or accentuate something and helps me tell even more stories.” He notes that he tends to work quite abstract—be it in fashion or portrait photography—and always seeks to enter a journey with the person he photographs. “You build your own little world,” he says to the sound of chirping crickets, pointing over to a neighboring field. “Even if we were to shoot right here right now, I’d begin by creating a world. When we both like the results it’s an incredible feeling of having completed something together.”

While other photographers might search for a distinctive style, Heinrichs values these encounters more than achieving over complex compositions and style: “The essence is in capturing authentic and tangible moments,” he says, referring to instances of people naturally interacting with their environment. “It’s filled with that sense of emotion and energy that makes imagery genuinely compelling, rather than just beautiful.” His meeting with singer and actress Charlotte Gainsbourg for Vogue Germany was a case in point. A rather introverted and distracted subject at first, her ability to let herself go impressed him. “Photography has a lot to do with the image you have of yourself. It can be liberating for the subject to give the responsibility for their image over to someone else who is not aware of one’s vanities and insecurities,” he says. Given that Heinrichs mostly operates within commercial realms, how do commissioners respond to this approach? “Commercial clients in particular long for authenticity, like we all do in some way or the other. I was fortunate to have collaborated with brands that spoke the same language.”

While you might think that he’s escaping by relocating to Flieth, Heinrichs rejects this notion. He says that he wasn’t searching for something new when buying land in Uckermark, that he had no reason to complain and that it wasn’t the case that something was missing from his life. Instead, the 38-year-old followed his intuition and “everything fell into place.” It’s not his intention to say goodbye to anything, but to look left and right: “I enjoy considering other people’s wishes, but I have to listen to myself more often and find time to slow down in order to grow personally and professionally. I tend to feel trapped inside a certain grid otherwise.” In Flieth, there are no restrictive schedules but the freedom to wait for the right light or a certain feeling. “It’s okay to just return with one image as long as I feel comfortable with that,” he explains.

Out here, Heinrichs satisfies his need to interact with nature as a balance to the busy surroundings his profession lead him to. (Heinrichs still rents a flat in Berlin’s Neukölln district). To date, the making process was at the core of Kleines Haus in Flieth. The open-plan house with its exposed beams, modular kitchen, fireplace, and bathroom is now completed. He is currently occupied with the design of the surrounding gardens for which he has joined forces with photographer-turned-landscape architect Rainer Elstermann, who settled in the area nine years ago. Together they browse collections of hedges—Elstermann is thinking a mix of French-style, playful, and eccentric—grow shrubs and flowering plants, and discuss the future of the premises’ remaining barn as well as the construction of an outdoor kitchen. Heinrichs is tossing around the idea of hosting artist residencies. Unlike many weekenders—locals’ term for house owners who descend on the region intermittently—Kleines Haus in Flieth shall constantly live as a creative retreat.

“Fashion is a framework that can support or accentuate something and helps me tell even more stories.”

Professionally, Heinrichs has extended his portfolio to landscape photography, something that only since moving piqued his interest. “Now that I have portrayed people for years, I am intrigued to discover the environments in which the person lives and include other elements,” he says. Thanks to the decrease of distractions in his daily life, he is more concentrated, more focused, and a bit sharper on set: “I tend to get stuck in a rut—office, travels, editing—that I’m finally able to overcome here. I’m more conscious with my surroundings and my interactions are much more honest. That’s another form of dialogue—just as it is in photography, it’s all connected.”

“It’s okay to just return with one image as long as I feel comfortable with that.”

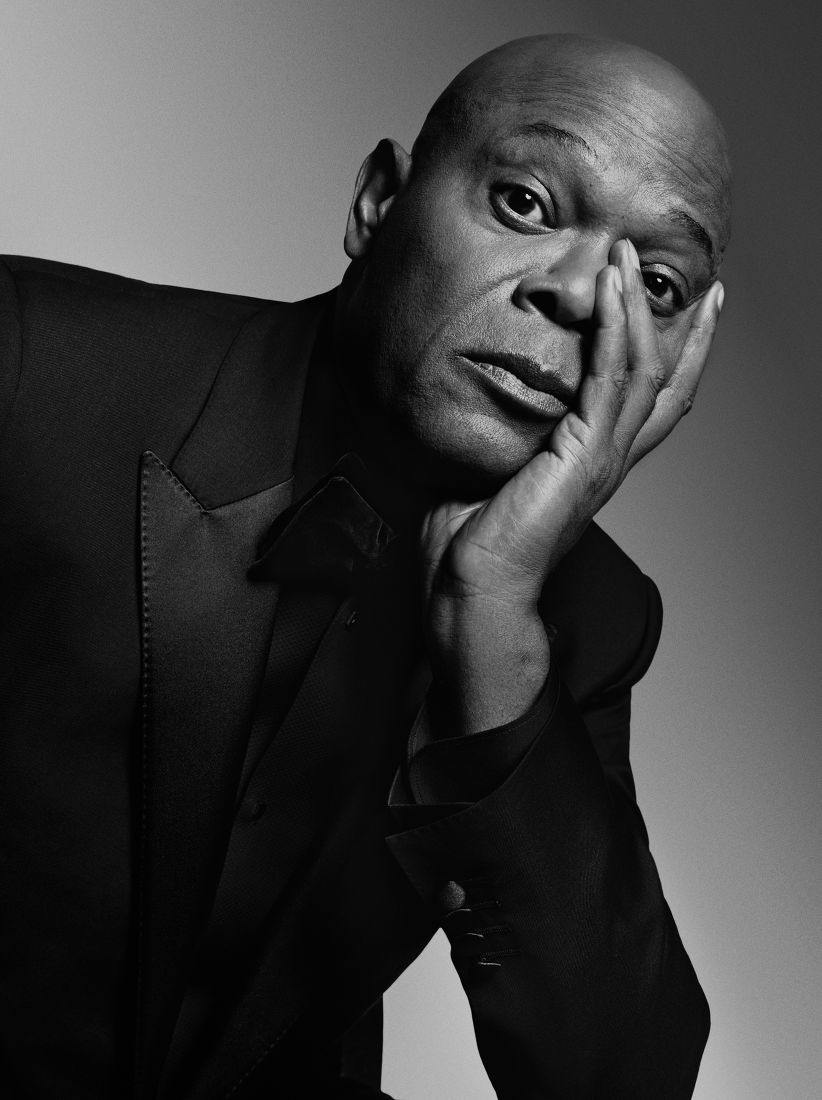

Stefan Heinrichs is a lifestyle and fashion photographer and filmmaker who lives and works between Berlin, London, and Uckermark. Having worked in the industry for over a decade, his clientele includes renowned brands such as Mulberry and Vogue. Follow Kleines Haus in Flieth on Instagram, and learn more about landscape architect Rainer Elstermann from his website.

This portrait belongs to our content collaboration with German fashion label Closed that highlights the lives and achievements of international creative tastemakers. It also includes the story of Antwerp-based landscape painter Nils Verkaeren.

Text: Ann-Christin Schubert

Photography: Robert Rieger