Julius von Bismarck is known for combining his curiosity for technology with his tendency for altering perceptions. Little wonder that his friend, the tailor Robert Vogdt, known to trade outfits for artistic works, decided to swap a made-to-measure suit for a print one of Julius’ feats.

Julius is most famous for his creation, the “Image Fulgurator,” which covertly projects images that are only revealed when a photographer sits down to edit the photos later. His ability to bend light extends into the natural world, with a recent project taking him to the jungles of Venezuela where he was able to trap lightning. The photo depicting his ‘straightened’ bolt of lightning is surreal and (pardon the pun) striking. “You shouldn’t artificially elevate art too much,” Julius says, looking around Robert’s atelier with a content smile. “It should be allowed to be around you as a matter of course.”

“You want to be naked all the time and there is no way you could wear anything beneath the chainmail.”

No artificial elevation is well and good, but Julius is particular about the placement of his works—the traded photo showing him beside an immense flash of light surrounded by palm trees was placed higher than usual, because the horizon sits low and, “the horizon is always at eye level,” he says. Robert was afraid the image could look too prim and proper if hung too perfectly centered on his wall, but the scene depicted here is far from bourgeois: shooting rockets into the Venezuelan sky during thunderstorms, guiding the lightning back to the earth in a straight line by means of copper-coated teflon wire. By straightening the flash, Julius’ goal is to tame one of nature’s many irrepressible elements.

Julius has been traveling to a thunderstorm-prone area of Venezuela —Lake Maracaibo, to be precise—to catch as many of them as he can. “This was a test rocket designed to bring down a flash,” Julius says gesturing at the photo. “But I didn’t believe it could, otherwise I wouldn’t have stood this close by.” It’s without a doubt a dangerous mission he’s embarking on—one that calls for precautions—such as chainmail armor made to defy multiple strikes of lightning. Unfortunately, the task of making the steel suits Julius ordered was too far away from Robert’s usual design ethic and materials. “You can’t believe the heat in Venezuela,” Julius told us back at his studio when he showed us these latest deliveries for his imminent expedition. “You want to be naked all the time and there is no way you could wear anything beneath the chainmail.” Despite the “enticement to create a steel fetish outfit,” Robert winks, he stuck to durable materials when designing outfits for Julius, hoping to send them off “to his next mission in Russia.”

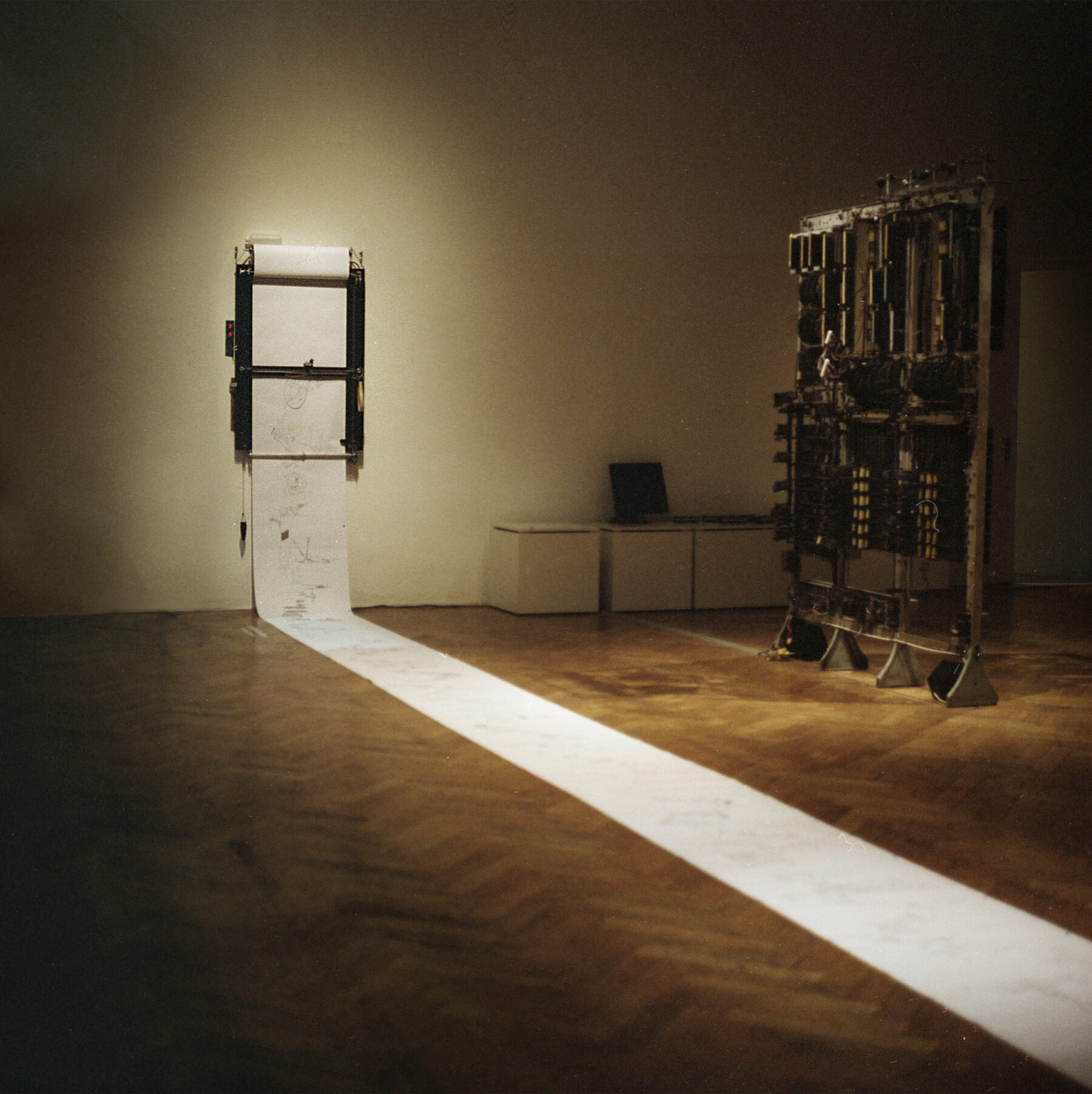

Alexander Levy Gallery

Walking through the gallery, Julius wears one of Robert’s jackets.

The will to create something infinite unites both creatives. Just as Robert has no interest in designing collections following the latest fashion, Julius urges that “I don’t want my work to be a mere commentary about ‘the now’, it’s meant to stay relevant for a long time.” Still, his projects are often inspired by current phenomena he observes in society. Rather than examining this philosophically, Julius von Bismarck tries to find artistic imagery—a straightened bolt of lightning—to express man’s relationship with nature and his will to suppress it, or better: make use of it in some way.

“Money is such an ugly currency to show appreciation for someone’s work. That’s why I like trading my work.”

One might ask, how does he fund these excursions? “I didn’t make money from this expedition,” he agrees. “In fact, I lost a lot of money with it. If I explain what I do to my tax adviser, he goes, ‘What kind of investment is this?’” He laughs. “It’s a pity we all need money to do the things we want to do. Money is such an ugly currency to show appreciation for someone’s work. That’s why I like trading my work. You know exactly how much time you spent on something and how dear it is to you.” Both Robert and Julius, it turns out, are experienced traders. “I used to trade my time and skills with other artists,’” Julius says. “In fact, trading was essential. Most of my early work wouldn’t have happened otherwise.” And Robert adds that he leads long-term relationships trading everything from handy work to food for his clothes. Of course, you can’t do without money altogether. “I need to obey the art market,” Julius admits. “I would love to sell certain things at a lower price so more people can afford them, but I have gallerists and have to refinance my expeditions as well.”

Julius’ studio in the Malzfabrik complex

Which brings us back to the framed photo on Robert’s wall—artistic proof of a piece Julius made to raise money for the Venezuelan project. Meanwhile, Robert’s list of clients couldn’t be more diverse—he has made kaftans and pajama pants for Burning Man, a vegan wedding suit, and just recently a new uniform for a general in the German Air Force.

The first outfit he tailored for the vision he has of Julius—a rugged yet elegant tweed suit—is a mix of inspirations. “When we tried this on for the first time, we both had to laugh, just because it is so spot on,” Robert says. Julius, who tells us he usually isn’t that interested in clothes, is already deliberating whether or not to wear his new suit to an opening that same evening. Though, his boots would have to be cleaned first. “There’s lots of Russian mud on them,” he grins, “from a festival two years ago where I was experimenting with a heavyweight ball that caused a mud explosion every time it hit the ground.”

Robert’s Kreuzberg Atelier

“It doesn’t feel like they’re clients; they’re guests. They come for a new suit and stay for a glass of wine.”

For the second outfit—a classic tuxedo at first glance—Robert has thought up some unique details. The one-of-a-kind meteorite cufflinks from Campo del Cielo, a meteor crater in Argentina, look completely Julius. “I collected the rocks and had a goldsmith turn them in to cufflinks and dress studs,” he says, holding them up before fitting them onto Julius’ shirt. The final touch is a bowtie, which seems negligible given Julius’ signature beard. Robert, who fights to fix it through his friend’s unruly facial hair, cheerfully tells the story of him embarrassing himself at a recent wedding: when asked to help out with a bowtie, the tailor had to admit he can only tie one on himself—a declaration of bankruptcy, according to one of the guests.

“I do like to be the one people turn to for their clothes, especially if they are my artist friends,” Robert says. “But actually, most people that walk out of this atelier become friends. It takes about two hours to conceptualize a good suit. You talk to the person to find out what makes them tick. That’s very intimate.” The procedure becomes even more intimate knowing that Robert actually lives here—a curtain separates his atelier and apartment. “For the people who come here, it’s so much more than just going to a boutique. You need to develop a level of trust with them. It doesn’t feel like they’re clients; they’re guests. They come for a new suit and stay for a glass of wine.”

Julius, looks like he would stay for a glass or two if it weren’t for his expedition starting the following week. “You can wear this when it’s over,” Robert suggests. “This tux is made for celebration. I, for one, have never been sober taking one of these off, and you shouldn’t be any different.” True, the Berliner’s occasion to wear a tuxedo might be scarce, but Robert stresses it’s only a matter of attitude and smirks: “I wear mine everyday after 6pm.”

Thank you for an inspiring day, Julius and Robert! To learn more about their work, visit their sites here and here. And check out the most recent works at the Alexander Levy Gallery here.

This portrait was produced in collaboration with USM as a part of the ongoing series, “Personalities by USM.” See a different angle to this story with a focus on Robert’s work here.

Text:Charlotte Wiedemann

Photography:Daniel Müller