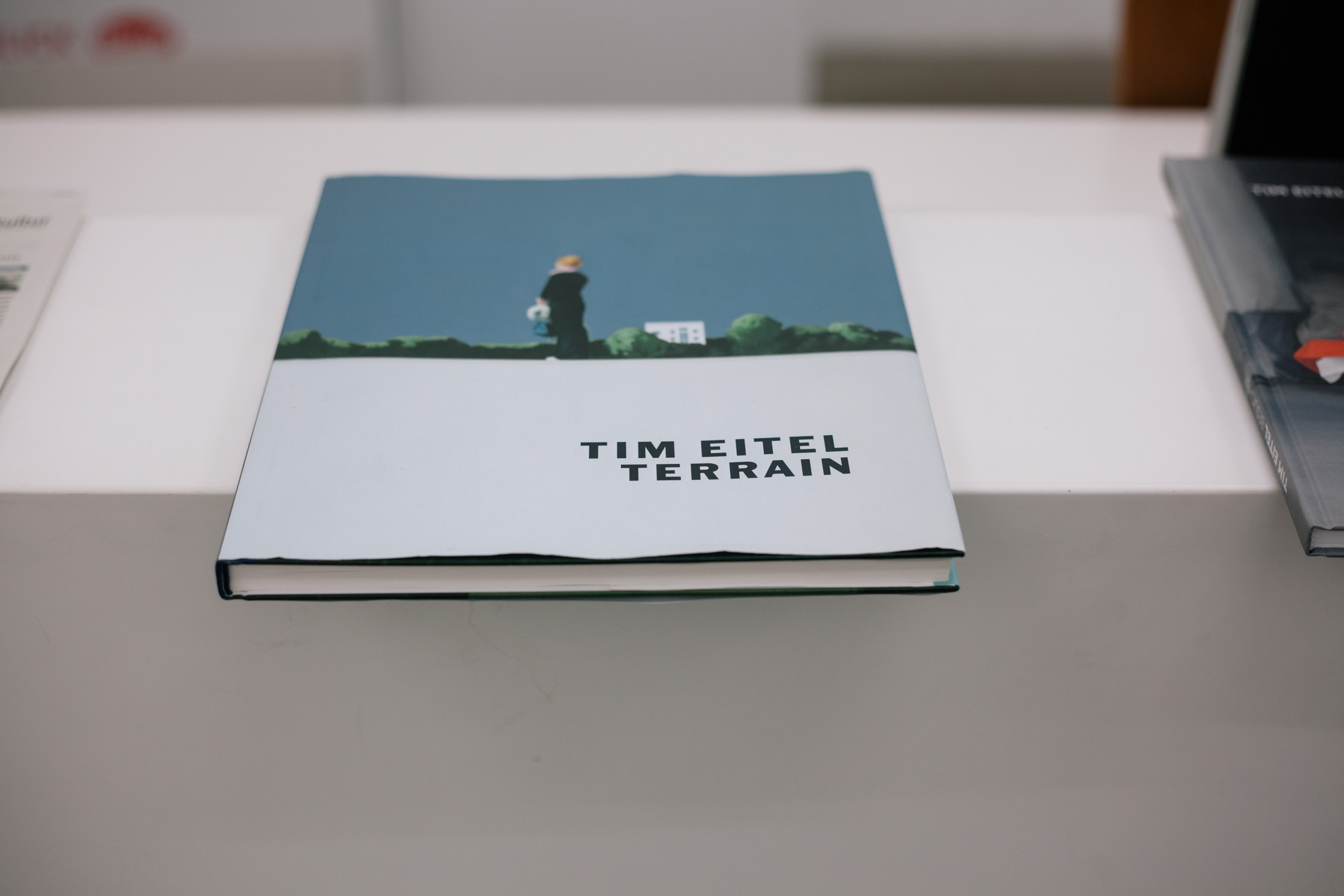

Dark lonely figures that seem lost in a misty landscape, piles of undefined clothes or garbage and black suns on a bright horizon. The paintings by the German artist Tim Eitel can be best described as discrete inconspicuous depictions of daily life. The backgrounds of his figurative paintings are often abstract, and their blurry – almost mystical – atmospheres highlight a particular omnipresent solitude.

The prestigious Art Review magazine declared Eitel as one of “the best young painters working today.” Tim offers a new impetus to painting in the contemporary art world. Convinced by the importance of painting, he co-founded the LIGA gallery in Berlin, which focused on the work of young painters from Leipzig. Having been awarded numerous awards and scholarships, Tim is represented by some of the heavy hitters in the industry: Pace Gallery in New York and Eigen + Art in Berlin.

Tim is a tall man, and in his dark jeans and black cashmere sweater, his appearance is as timeless as his work. Once you enter the stark white studio, outside disturbances seemingly belong to another world. In the heart of the bustling Berlin neighborhood of Kreuzberg, the artist has established a tranquil oasis.

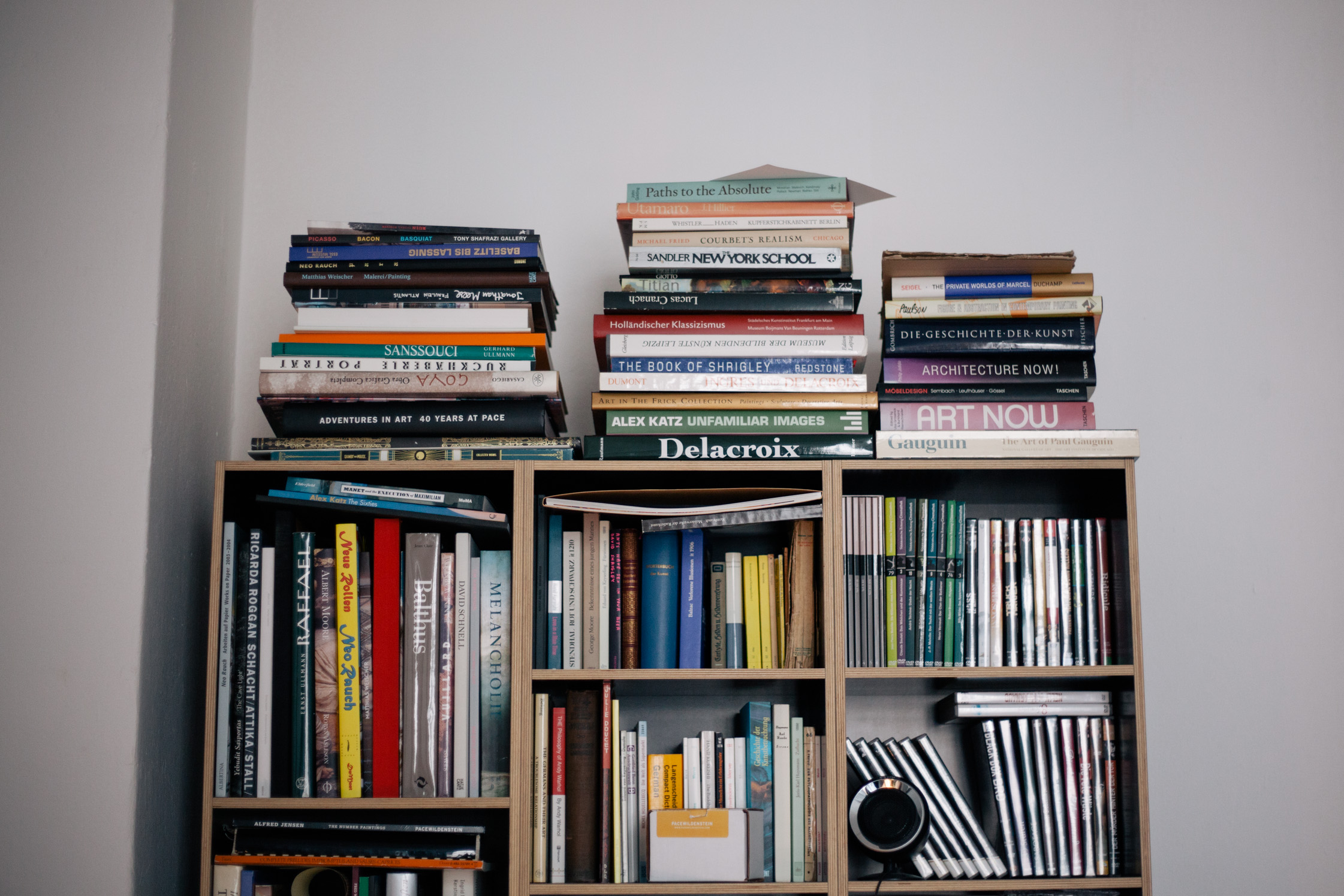

In one of the most organized studios you can find, a table is filled with brushes in one corner, in another, piles of paper rest on a desk and orderly canvases lean against a wall. Furthermore, the spacious studio is empty; no fringes, no adornments. Tim speaks in the same economic manner, precisely yet softly. As a watery sun defeats dark thundershowers in the distance, he pauses often; hesitates, stops and re-formulates his answers.

Before attending art school you studied philosophy and literature, were they your first loves?

I was already interested in painting, but I couldn’t get around to filling out all my applications. At first I studied philosophy and literature at the University of Stuttgart for a year. Then I went to Halle to study painting. Halle was actually my seventh application, the other ones – Nürnberg, Dresden, Leipzig, Stuttgart and Karlsruhe – all rejected me. As you can see I was quite determined, you have to be. But now looking back at my portfolio, I would have rejected myself too.

What was so bad about your portfolio?

It was very technical. There wasn’t much of an artistic viewpoint. I had this idea in my mind that I had to learn the basic rules of painting before I could really go into something more complicated. That’s why it was very basic technical stuff, like still-life’s, portraits, shadows and the layering of paint.

And after two years you moved from Halle to Leipzig?

That was the school I really wanted to go to. Before applying I visited many schools. I really liked the city and atmosphere in Leipzig immediately. As soon as I left the train station I could feel its good vibes.

You were a Masters student in the famous painter Arno Rink’s class. Did he influence your work?

Arno Rink was part of the real Leipziger Schule from the 60s and 70s. He was a very good teacher because he would always encourage people to do their own thing, to have their own vision, and to question themselves. He didn’t want anybody to follow his path. So yes, in some ways, he did influence me. Not stylistically, but certainly in a critical sense from organizing a two-dimensional structure, to a very abstract way of thinking and especially in being self critical.

Abstract without a narrative?

For him narrative is private. He never really talked about it, even when it was obvious. That was his viewpoint. But this doesn’t mean that I agree with it.

After graduating you moved to Berlin. What happened next?

A year after I received my diploma, I moved to Berlin and with a group of artists from Leipzig I opened an artist-run gallery in Mitte for two years. The gallery was called LIGA. There was a new interest in painting developing at this time and people also started looking a bit more towards the East. That’s when our group of painters from Leipzig came into focus. People called it ‘Neue Leipziger Schule’ (New Leipzig School), a kind of silly and lazy label. My generation had a very different situation than the generation of the “old” Leipzig School. They didn’t have the possibilities we had and necessarily our approach to everything was very different. Also probably half our group had grown up in the West.

Being a group of artists, how was LIGA organized?

Well, it was organized like a gallery. We even had someone do the job of being the gallerist. We thought we were incapable of doing that. At the time the idea to make money with painting was ridiculous, the new wave hadn’t started yet so we were quite sure to lose a lot of money in our project. In the second year people started coming, critics, collectors and gallerists came to LIGA to see what was going on. It’s funny because people often said that this self-run gallery project was such a clever move. Afterwards there were certain other projects that kind of copied our model. We ourselves just thought we were burning money because we needed to pay rent and materials. After that I joined EIGEN + ART.

Was it a new light on painters from Leipzig?

I think it was a new focus on painting in general. We created an environment where people started becoming interested in painting. But I always thought it was a shame that it was mostly the painters from Leipzig who got all the attention as there always had been very strong photography and new media art. It probably didn’t fit into the simple narrative.

You were born in a small village in the former West, near Stuttgart. A few years after the Wende you moved to Leipzig. Did it make you more aware of political issues in art?

Maybe I became more aware about the issue of the necessity to protect your freedom in art. Even in our open society you still have to protect it. Hard to see any direct influence though, as environments and people influence you on a more subconscious level.

Looking at your work, your subject matter is directed towards cultural and social issues, yet it is not obvious. As a viewer you can see it but also ignore it. For example with the paintings of homeless people – there is no overt moral judgement.

It is more about the idea of showing or presenting?

It is painting and transposes our world into another world. In this way, painting is more like theater. It is abstract. It is a an actor playing a homeless person on a stage – especially with the dark paintings. Just imagine a stage all in black, no light and just one spotlight on the protagonist. It is a lot like that. It creates this artificiality. In the end painting is not a documentation, it’s about ideas.

As part of your working process you take your own photographs. Do you reference them before you start painting?

I use photographs as a memory tool or like a sketchbook, in which I use or combine elements of photographs into my works. During the working process I also change the imagery a lot. It’s a long process. There are always new associations. I react to the source material and create different diversions.

Pictures are very directly extracted from reality. However, your paintings aren’t so direct – they are blurry, misty almost. Is it your way of dealing with reality, by creating it in soft-focus and therefore less painful?

I think it wouldn’t feel good to stay too close to the real document, because in some cases it would feel like exploitation. It has to have this transposition into the artificial painting world, to become something else. It becomes more of an idea, less the harsh fact, but the idea of the fact. They become a new fact as a painting. And I don’t want them to be judgmental.

Did you ever exhibit your photographs?

No, but never say never. At the moment I’d say no. I don’t see them as artworks. It’s material for my personal use, for research. But who knows, maybe at some point it could be interesting. Maybe as a book they would work better than in an exhibition.

How do you approach photographing tragedy; revealing harsh reality and showing it as art?

It’s not something I am very interested in because sometimes it’s just too much. It’s such exploitation to show the misery of people through huge prints and show them in a gallery and then sell them to a collector. Of course, it’s a problem I had been thinking of in regard to my paintings as well, so I try never to do something that would exploit anybody.

I haven’t seen any full frontal portraits in your work. Only the self-portraits are en-face. All the other portraits depict people walking away, only showing the back of their heads or a side of their face; they are all isolated. Does that have to do with your fear of exploitation?

Yes, in a way. At the same time it is very hard to have a face in painting, especially if it looks out of the painting to something else. Then it becomes too much of a portrait, and immediately people look at the face and it becomes the main focus.

Do you ever paint portraits with faces?

I do it sometimes. For instance there is one painting of a couple, who are sitting in chairs. The guy has his back towards the viewer and slightly behind him is a girl. She looks out of the painting, like something is coming from the sky, like a light or something. The interesting thing is that they are almost one form because they are very close together. Almost as if they were one body. At the same time they are completely apart, and there is no real interaction between the two. Maybe a good image for what is going on in our brains.

Did you see this couple somewhere and photograph them?

No, but I saw something similar. The situation was different because it was at a big dinner table with a lot of people, with the two of them just sitting there at the end.

Nowadays, there is quite a hype on painting with big shows such as ‘Painting Now’ at TATE London, or ‘Painting Forever’ at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. What do you think about this?

I think this whole thing about painting is always happening. But it is kind of funny because nobody makes a show called ‘Video Forever’. It’s interesting that painting since the 70s had this problematic feel to it, like it somehow stands apart and is special. This old tale about painting being dead – and now it is here again. It’s funny that other media shouldn’t have the same problem.

But how do you perceive these painting shows, for example at the Neue Nationalgalerie?

It wasn’t just the Neue Nationalgalerie, the show was throughout the city: at KunstWerke, a component at the Berlinische Galerie. I didn’t see everything, but I thought the whole concept was ridiculous. They didn’t have a concept. Every institution did it’s own thing and it wasn’t clear if they wanted to show the state of painting as it is today, or if it was about painting in Berlin, or about something else. There was no coherence.

You did better with LIGA?

No, but it was a gallery, not a museum. So there was no need to any kind of objectivity. We showed the artists from our group and invited some friends.

As a painter it must be reassuring that there is a newfound interest in painting. How do you view this reinvention of painting?

At the moment there isn’t such a hype around painting – which is probably a good thing. This was more like 10-15 years ago. Nowadays we don’t see the work of so many painters in museums, as a lot of curators still see it as problematic. It is not integrated in the whole spectrum, it’s not in the biennales, at dOCUMENTA; it’s still a bit like this: there is art in all kinds of media and then there is painting.

I think you are right, but at the same time there is a trend towards a more integrated reception of painting. Don’t you agree?

Yes, something is beginning to change again. There is a more specific interest in certain types of painting. Especially with the younger curators who don’t believe in the boundaries between different media anymore, because it doesn’t make sense to separate photography and painting. Sure, it is another medium but it makes no sense to not no show them together. They all are interrelated and influenced by each other.

You also live in Paris and have lived in New York and Los Angeles for a while. Do you think you paint differently in each city?

My environment influences me a lot. You see different things in each city, the atmosphere within the city and in every neighborhood can be so different. However, I don’t think that it is environment that specifically influences the work I make within these particular environments. It is more the accumulation of the whole atmosphere of being in Berlin or Paris. Actually both cities have an influence on everything I am making at the moment as I am always living in between; I am never completely in one place.

Does this liminality make you a better observer?

I don’t know. It is a different way of observing. There are observers who are very precise within their environment. Some can deliver a precise image. Maybe for me it is more an observation of differences.

Is there a particular artwork that had a strong impact on your practice in recent years? Something that influenced the development of your current work?

There was one actually last year. I underwent something like a break-through that sparked a whole new direction. The result can be seen in my latest exhibition at Eigen + Art in Berlin. It was a painting of a sun. Last year I did a large painting that was kind of a positive predecessor of the two paintings that are in the show – two black pieces called Black Sun. It had a very similar composition and was called ‘Sun’. When I started the painting, it was a figure, more like a silhouette in front of a large sun. Halfway through the painting I realized that the figure didn’t work. It was too narrative. So I got rid of the figure and came to a landscape that was like an image of an inner state. This started this whole kind of more “philosophical” approach.

Because it is more abstract and less about the narrative?

It is more about ideas; of passing from one moment to another. There are a lot of paintings that exist as ‘couples’ and belong together with a small ‘moment’ that divides them.

Almost like yourself.

Yes, I am always somewhere between cities and the paintings I guess.

Do you think in future the narrative will become more abstract in your work?

Yes, maybe, it’s always hard to talk about the future. Especially when you have just finished a show. Then you have to get your mind around it. I have no idea what’s going to happen.

Keen to see more of Tim Eitel’s work? Visit EIGEN + ART Gallery for Tim’s current exhibition ‘Nebel und Sonne’ that runs until the 7th of June, 2014.

Photography: Marlen Mueller

Interview & Text: Mirthe Berentsen