The Swiss born Australian raised artist Tom Mùller is a man of dichotomies. As a child, Tom grew up in the picturesque Neuchâtel, but once he hit his teens he and his family moved to Perth – the world’s most isolated city. Experiencing both the rich history of Europe’s past, alongside Australia’s relatively recent cultural identity, has greatly influenced the way Tom views and interprets his surrounding landscape. This keen sense of observation is made most evident in his artwork; Tom’s work touches upon the natural environment alongside what is constructed. He explores the blurring of global boundaries and reconfigures our understanding of transnational sovereignty.

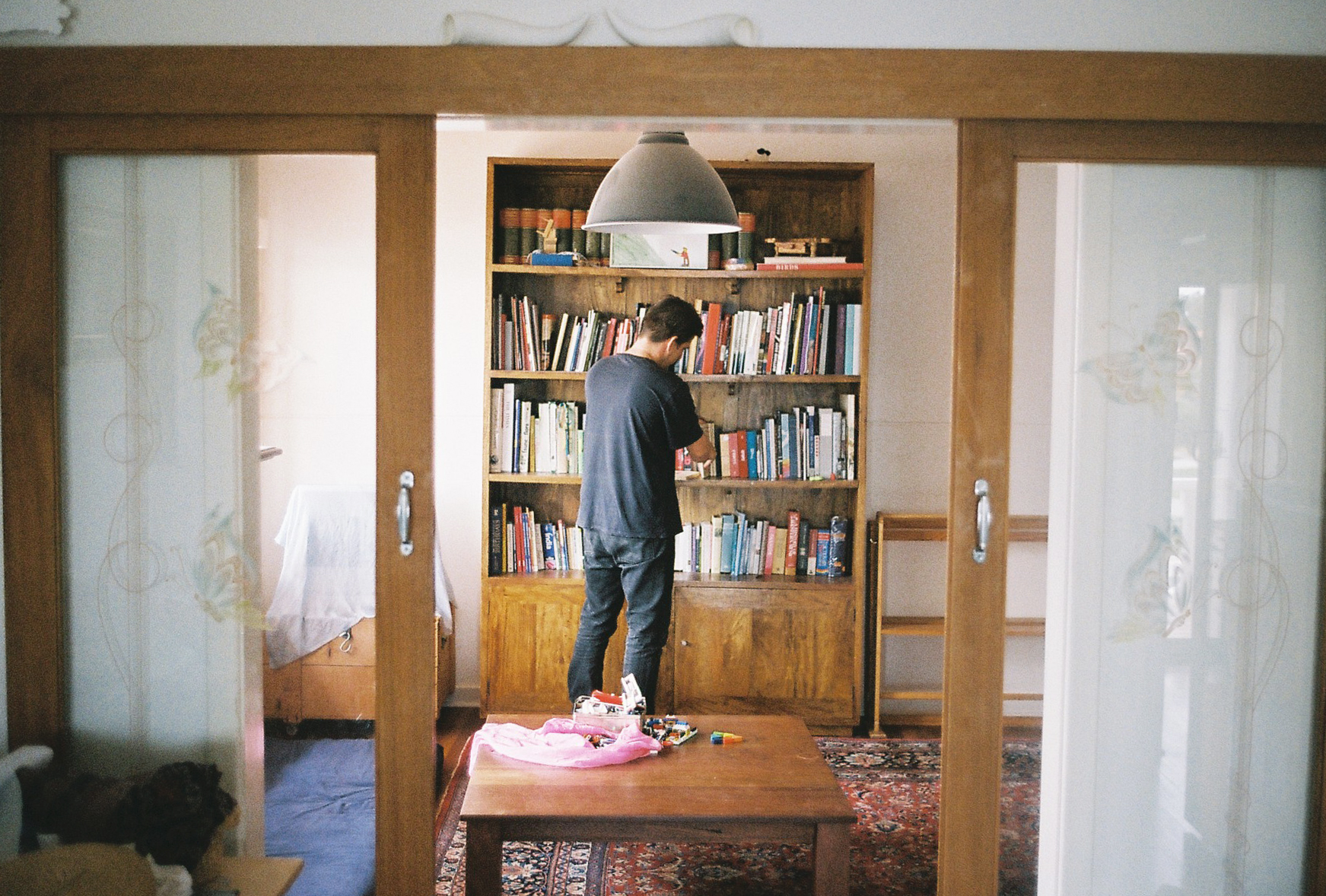

While much of Tom’s time is devoted to his practice, he is also the manager of PS Art Space in downtown Fremantle and is a father of three. He and his partner Rochelle Phillips and their sons reside in a beautifully renovated Portuguese villa. The building is all whitewashed pillars and arches on the outside with polished concrete floors, and minimal furniture within. A large open-plan kitchen looks onto glass windows through which lies a sun soaked backyard. The furnishings are simple; wooden tables and chairs that add a feeling of warmth to the space. Handcrafted toys, games and puzzles are scattered throughout the house and the garden is strewn with child-sized bicycles. With the sound of chickens clucking in the background, Tom speaks of his childhood, growing up in two very different cultures and the nature and direction of artistic possibility.

Despite having lived in Australia for many years, you grew up in Switzerland.

I was born in Basel. I was there for the first four years of my life and then we moved to a small village in France about two thousand meters above sea level with pristine landscape and valleys. We stayed there until I was 17.

How did growing up there affect you?

The French part was really a fairytale landscape, with cows and Jura mountains. We spoke French at school and Swiss German at home as both my parents are from Basel. My dad was a GP and we moved to that village because of his job, but we were perceived as foreigners.

Yes, village communities are often very tight and interiorized.

Totally. Our village had an interesting mix of residents: Portuguese, Italians, the village natives and, obviously, us. There was a lot of tension in the beginning. This Syrian guy and I grew up together as we were both foreigners in our own country. The rest of our family all lived in Basel, so we used to visit them every second weekend.

So the house of Le Corbusier is in the canton of Neuchâtel?

Yes, there are a lot of traces of his work. The whole landscape there embodies some of his architectural language. Both my grandparents and other relatives are architects, so we grew up with a strong sense of that point of view. Even the house we grew up in was interesting and very symbolic for us. It was built in 1520 and used to service the count of a castle nearby. My grandparents bought it in the early 1950s and renovated the whole house.

So you were constantly surrounded by artistic endeavor from an early age?

Yes my grandma, uncle, and aunt are all painters. Lots of neo-bohemian influences around, which was great.

Let’s talk about the two countries, as they are so different culturally. What was it like leaving the historically rich Europe for an unknown new country?

When we first came to Australia I was 17 and I really didn’t want to go. It was after my dad passed away and my mother wanted to travel and do something else. She came here three months ahead and scouted out the best city for us to live in. She knew a couple of people in Perth and that’s how we came here. When we arrived my brother and I went to Foothill School in Guildford, which was very interesting culturally.

We knew how to speak some English, as my grandmother is Puerto Rican. She had spoken English to us since we were kids. We had some sort of grasp of weird Hispanic English and after six months or a year we had pretty much adopted the language. But at 17 I was a graffiti artist and a bit of a bad boy travelling around Europe. I even got two years parole. We had our crew back then, and I was sort of ripped out of my crew so I wasn’t happy about that.

Did you notice how new and different Australia was as a country when you were young?

I did. I mean at that age I didn’t give a shit. But yes, the main thing that struck me was the architectural landscape. The exposed brick was a big thing for me and quite shocking.

You were well versed in architecture. It is interesting that this was one of the things you were aware of.

My graffiti background played a big role in this. I was always seeking new walls and opportunities to paint stuff. Brick was very limiting as its pattern would override any content and design.

Perth is the most isolated capital in the world. Do you still notice that now so many years later?

I value that about this place. It is a cultural oasis in some ways. It incubates in its own kind of genre. Music is a great example of that. Music has its own kind of style devoid of any major geographical influences. This isolation has brought a unique type of language to this city. I suppose with the advent of a lot of travel and being able to reconnect with the major cities, it doesn’t feel as isolating. We are going to Basel and Tuscany later in the year. Travel is a bit more limiting now with kids. We all love travelling, it’s fun. So in general, Perth is great and quite unique in a sense.

There are divided views on living here. A lot of young people rally against this isolation.

I understand that if you are born here you want to see something else and it’s actually imperative that you do.

Moving more into the artistic realm, what drew you to making art in the first place?

I wasn’t always an artistic child but I suppose graffiti was there. I was 14 when I started. We had a very strong connection to the whole hip hop movement at the time which was still in its early stages in Europe. It bloomed in the late 70s in New York and arrived in the mid 80s in Europe. There was a sense of family and community. Breakdancing, sparing and tagging created different types of cultural language. The urban environment was very important to the hip hop scene.

So there was always a dialogue between you and the landscape?

Yes, just the landscape around me. Why be a passive participant when you can actually engage in your surroundings? Sometimes it is a bit more vandalistic of course. I wrote a manifesto about all that along with two friends from university. If children in rural areas ploughed and cultivated the fields then why couldn’t kids growing up in urban environments do the same with their concrete landscapes?

What was the reaction from your family?

They supported me in many ways as I came from an artistic family. However, the idea of vandalizing property, which we did in some respects, had to be justified and that’s what the manifesto did. Even though it was a very primitive manifesto (laughs). I did graffiti for years and I wanted to prove to the rest of the world that graffiti was its own legitimate art form.

After a year or so into art school, I dropped graffiti as I started non-figurative painting. It was a good time I suppose since I had a few shows and sold some good paintings.

Why painting? Was it a natural progression?

Yes, because you could push the medium in how you apply paint on the surface. Non-figurative painting is about capturing the essence of something with a few lines or patches of colors. I was all about creative experimentation for years exploring the connection between graffiti and art.

Today, your art doesn’t show many traces of graffiti. Do you remember when you let go of it?

I remember I had a dream where I was on a bridge in Basel. I had a box which contained all my world of graffiti and I kind of threw it into the river. The next month I completely abandoned it. I still do graffiti for birthdays gifts and things like that, but I have tried to completely let go of it. I don’t like how the culture became so americanized and over-commercialized. It lost its initial rawness which I loved. I still make sketches but not in public spaces anymore.

Does graffiti on trains still happen in Australia?

Yes, in Sydney you’ll see quite a few. Much less here in Perth as it’s too gentrified.

You published the book ‘Rhythms In the Chaos’, that appears to outline the globalized nature of the world we live in. Correct?

Yes, that comes back to your initial question about how two cultures assimilate. The first and second part of my life. I’m not looking at a globalized world view of where things are depersonalized, but rather, for the individual kind of strengths in a collective sense. One of the pieces is basically a blue background where each political nation has been superimposed. In that picture you lose any sense of boundaries, but you can see this sort of god-like, cosmic pulse. All the small nations are assimilated and you can still see the bigger ones. For me, that’s the zeitgeist that captures what the term ‘globalized’ means. It’s about losing sense of who you are. The works are just comments and don’t mean to advocate the way we should be going. It was just how I was interpreting the landscape around me.

Is this something you have been interested in for a while now?

Yes. The ‘world passport’ is a very big part of my career and artistic development. I had to deal with all the controversy attached to it. You know, I was arrested by the FBI and taken into interrogation because of my artistic practice. I was in New York three days before 9/11 and I had sent back a bunch of blank passports. I was also photographing ambulance suits and cars for a project I’ve been working on for nearly 15 years. It was about photographing ambulances and underworlds.

At that time, after 9/11, the apotheosis of the second half falling down was that ambulances were driving to the tower structure as people thought that the second tower was bombed. So in the heat of the whole fear factor I was pulled in for interrogation and they checked my house.

And this all happened because of these world passports you were creating?

As an artist I found it really interesting that my work had generated so much response beyond the artistic audience. It was great. I had a website and I was making lots of passports for people in Kongo, Brazil and Zaire. They all saw this passport as this currency of freedom that would help them belong to the new world but, obviously, you can’t have a world passport.

It’s kind of ironic if you think about it. There was a real need for this thing to grow into something massive and it was all very exciting. I could knock out a passport in half an hour for a fee. It was part of a performance that spurred on a whole range of other works, like the gold credit cards. It’s all about the way we value things and what’s valuable. All these elements of power, like passports and credit cards, can shape and change one’s destiny. My artistic point of view is to reconfigure and reinterpret what these objects can do.

What do you think about the artistic community around you? Do you think that art and how people react to it has changed a lot?

It is hard to make an objective, informed comment but yes, I have seen change. It has evolved from being a more traditional and romantic view of an artist working on their painting language to working on collaborative projects and combined practices. I think there’s been a huge shift in the last ten years. Today, it doesn’t matter how you make something or if you have it made by someone else because it’s more about generating ideas and collaborating with other artists. The actual process has become much more important nowadays.

Having a more human interaction stands at the core of the new art practice as it’s all about the social involvement and how the audience can participate in an art work. It’s not just about how great something looks, but how a person can bring more meaning into it which, in turn, can inform how the work develops. I think that’s the future, to be honest. If you think about it, it’s a very selfish activity because through my art I get to indulge in my way of looking at the world. However, when other people participate in the work they render it a selfless activity since it provides a platform for real dialogue which is more interesting.

As an artist and editor for a space for artists and as a father of three, how do you balance your different roles?

It’s a bit tricky. Morning and evening is family time, of course. I don’t go out as much as I used to, I’m growing up and some things have to be left behind.

Before Perth you were living in Basel. Is it a hard culture to break into when you are not from there?

Yes. Extremely. Even being from there is difficult. I love so many aspects about Switzerland but socially it is very difficult.

Even though it’s a tight community, would you go back to live there again?

Yes, we talk about it quite often. We love Basel, it is a great city. Maybe not Switzerland. I would love to go to Berlin and New York is fun but quite hard to make a living. We gravitate towards our kids and their needs a lot, but of course we long for more flexibility.

Does your family life have an influence on your work as an artist?

I suppose yes. It probably dictates the way I manage my time and what kind of projects I take on. I guess you are much more resourceful the older you get and your time is precious. So, yes, family life has certainly changed how I tackle things.

Photography: James Whineray

Interview & Text: Lucy Byrnes