Together with our friends at Faculty Department, we met the Los Angeles-based duo to learn about their partnership, the uniquely amorphous quality of their work, and why idiosyncrasy and obsession are the best defining characteristics of any artistic pursuit.

It’s endearing watching Leigh Patterson and Michael A. Muller evade the question: what do you do? The insistent distillation regarding how they spend their time bores them, and their ennui from over-describing their work is clear. It’s easy to understand why. There’s an ineffability to their professional interests, and their projects resist easy classification. Leigh is the founder of the creative studio Lucca and writes the incredibly popular workbook series Moon Lists. Michael is a multi-instrumental musician and composer. He is also the co-founder of the band Balmorhea, a genre-eluding instrumentalist duo with a worldwide audience. Balmorhea released its seventh studio album, The Wind, in April on the historic Deutsche Grammophon label. He also released a solo project, Lower River, in 2019. These titles feel only partially summative regarding “what they do,” though, and they enjoy occupying this malleable space. Michael and Leigh’s creative styles can be defined, in part, by their measuredness and their immediate recognizability. There is no false step, chaos, or excess. There is also no one doing quite the same thing. There is an order, a watermark, to all of their projects—a vernacular spoken and identifiable species inhabiting their creative worlds. Because of this deliberate consistency, small moments of change or perspective shifts result in large emotional resonance in their work.

Leigh and Michael met in Austin in 2009 at a Balmorhea show. “I was sitting at the merch table while the opening band was playing,” Michael says, “and Leigh walked in. I am an INFJ, so approaching a stranger felt very out of my comfort zone… but after hyping myself up, I walked over and introduced myself. A few days later we met for a coffee, talked all afternoon, and then – after we’d only been dating for a few months – moved to New York together.” When asked about their early relationship, Leigh says, “I think immediately it was less of a bonding over hobbies or what we had in common and more of just the feeling of being at home with another person, even though we were complete strangers. Our relationship has really given me a better understanding of how to simply feel when a connection with another person is there without overthinking the details.” After moving back to Austin and predominantly living there for another decade, they moved to Los Angeles this past winter. They attribute the landscapes of their childhoods to their adult notions of home and place. “Most of my adolescence I just was wanting to get out [of the Texas Hill Country] and move to New York,” Leigh says. “I still wrestle with that push and pull, between craving the pulse of a city yet recognizing that I feel most at home in a vast, more isolated landscape.” Michael agrees that the memories of his early childhood in San Diego shape his adult ideas of feeling truly centered: “My most visceral, sensorial memories come from some moments there: eucalyptus, hiking cliffs on the edge of the beaches, the quality of light in the summertime, looking out the window of my parents’ car, listening to Paul Simon’s Graceland on repeat. I think about those moments often, trying to rediscover that sort of weightlessness and dream-like quality I felt. I think subconsciously those are feelings I am somehow yearning for in my own work.”

“Our relationship has really given me a better understanding of how to simply feel when a connection with another person is there without overthinking the details.”

There’s an aphorism by the writer Annie Dillard that Leigh considers often: “How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.” While this notion could feel accusatory to some, commitment and daily ritual seem to offer liberation to Leigh and Michael. Leigh grew up as an only child with two career-driven parents. From early on, she shaped her inevitable solitude into something delightful and manageable. She became curious about big ideas that she could entertain herself by indefatigably trying to explore. “It really wired me to find comfort in independence and solitude,” she says, “buried in books and magazines, making zines, and writing undoubtedly unhinged things (that I thought were genius) in my very earnest LiveJournal.” She has continued to spend her days asking herself and others big pointed questions, and she has made a career out of pushing individuals to think critically about their answers.

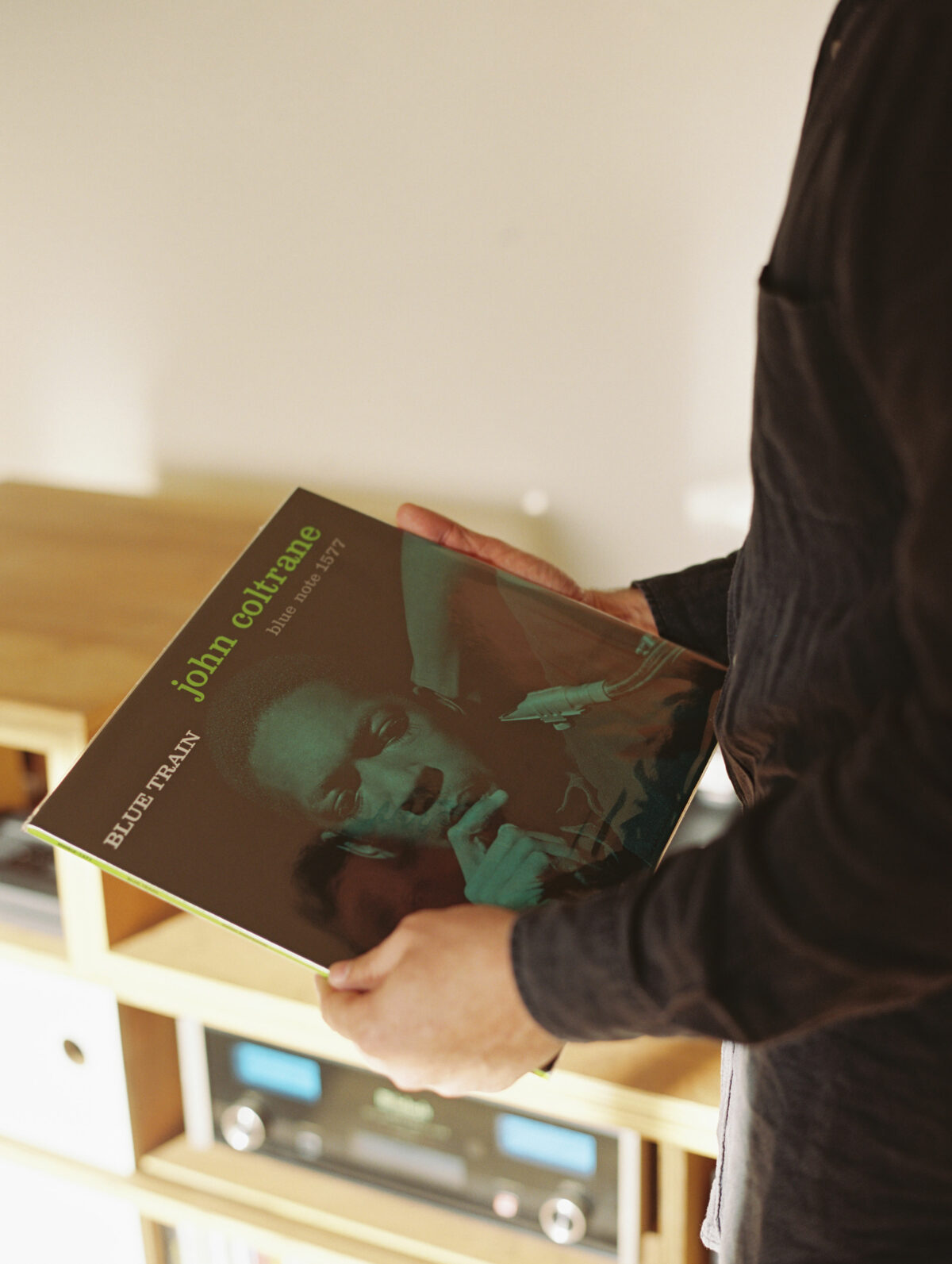

Michael’s childhood in California and Texas was also spent with a solitary, yet singular passion. “I think the same interest from my childhood defines and occupies most of my time in my adulthood: music – specifically, guitar,” Michael says. “I got my first guitar at age 5 and haven’t put it down for more than a few days at a time since. If not playing or listening to music, I am constantly thinking about music or listening to someone talk about it. As a kid, I’d sit for hours studying and listening to albums on repeat, reading the liner notes, memorizing the melodies and the lyrics. It was truly an insatiable appetite for the feeling I got that only music gave me.” This intrinsic obsessiveness is what separates hobbies from vocations. Michael constantly immerses himself in new forms of music—not as a way to become more knowledgable, but because this insatiability is the lens through which he sees the world. “For the past several months,” he says, “I’ve been captivated by the music of the kora, which is an ancient instrument primarily played in western Africa. It consists of a hollowed, bead-adorned gourd with a wooden neck suspending 21 strings vertically. Out of the top, there are two small handles which the player places in the crook of the thumb while plucking the strings with their fingers. It is most similar to a lute in timbre and has a harp-like quality to the attack of the sound that resonates from the pluck. The Malian player Ballake Sissoko is one the highest regarded contemporary players of the kora and has a handful of beautiful recordings but one I recently found on vinyl is a collaboration he did with a French cellist named Vincent Segal entitled Musique de Nuit. The contrast between the two instruments is truly stunning and fully demands attention. There is an innate, fundamental, and rudimentary energy that exudes from the music; it feels like it has always existed.”

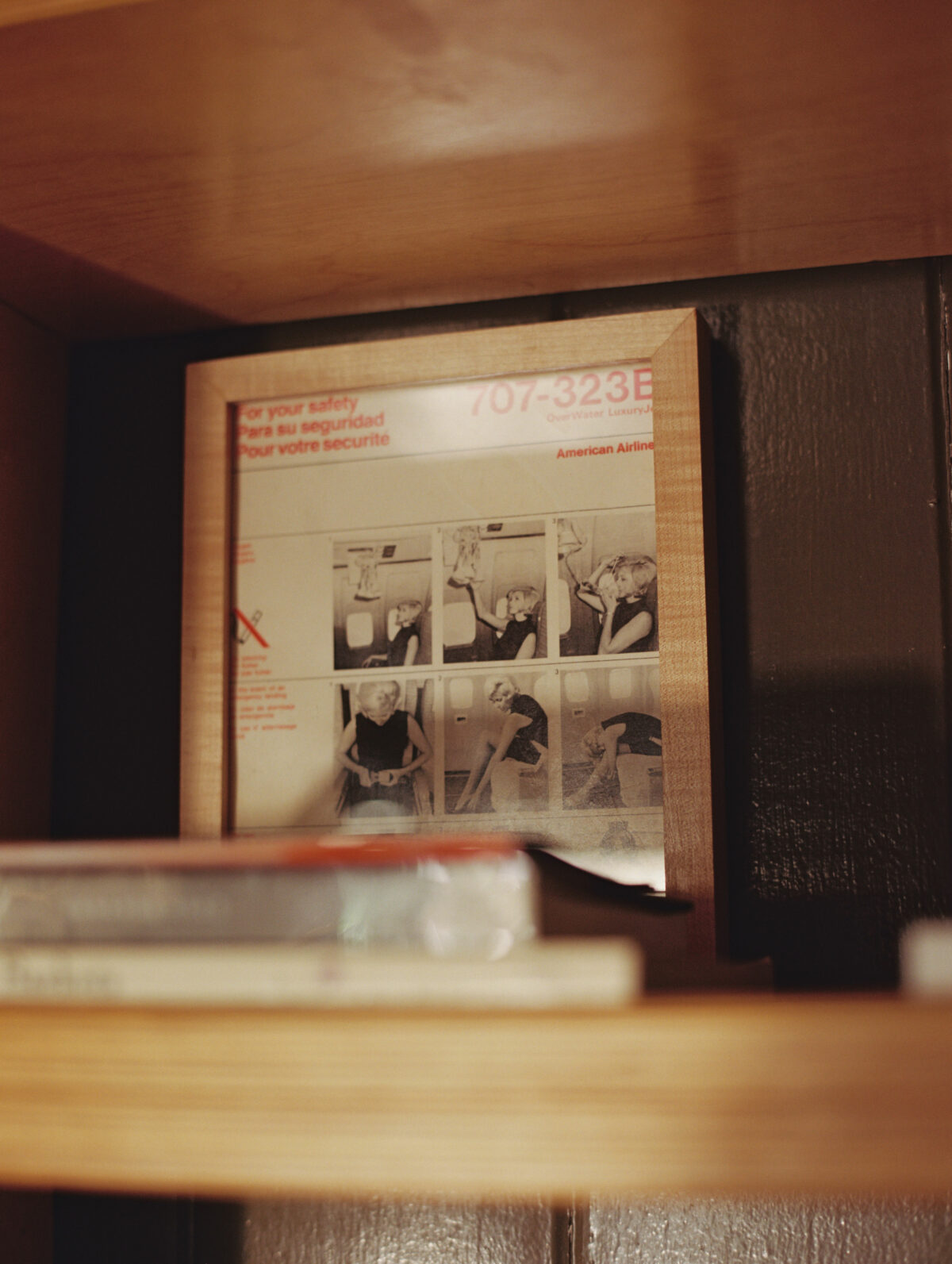

Like so many great artists, it’s the restlessness and refusal to be constrained by definitions that makes Michael and Leigh worth paying close attention to. Well, that and the fact they’re surprising odd-balls, despite their lean and intentional visions. Leigh loves listening to a good, shocking story and Michael loves recounting weird, funny moments from his recent past. Leigh will try just about anything once, just to see how it goes. Michael will meet a stranger and enthusiastically hear their entire life story. They love collecting interesting objects—from rare records to strangely found ephemera to out-of-print books to little bits of nature ferreted on walks. They also love people-watching. One of their favorite things to do is to go somewhere together, buy a drink and snack, and sit and observe strangers. Cy Twombly famously loved people-watching at Wal-Mart, and the intentions feel similar: minutiae of the human experience fascinates them—the things that often slip through the cracks, or occur when we hope no one is looking. Michael shares that he’s reading The Flower Shop by Leonard Koren, which is about this sort of devotional attention to the world. “It’s a very simple book about the author’s obsession with a Viennese flower shop,” he says. “In his research, Koren visited the shop daily and would just sit and observe the staff, patrons, the light, and the space… from a more zoomed-out perspective examining how certain places can hold a specific, one-of-a-kind magic. It’s a nice reminder that you can’t fully “understand” something by social media or secondhand accounts specific places hold a quality that can only be really understood by being there at a particular moment in time.”

Similarly, this empathetic, textured attention is what breathes life into their sparser sensibilities. Instead of their projects feeling minimalist, they feel accurate. They feel clear—tinged by unexpected verisimilitude to how life feels. Levity and gravitas, high-brow and low. So often, a minimalist aesthetic can feel too ascetic, devoid of humanness, and uninviting. Bare walls, light wood, beige art, one-note struck again and again. But they imbue warmth, nuance, life, and flexibility into their work. They give their imaginations long leashes while remaining tethered to the discipline of their visions.

“Unearthing better ways to understand, recognize, and develop a vocabulary around the ‘you of now’ is much easier when you start with detail.”

Lucca, Leigh’s creative studio, works with brands, individuals, and organizations on editorial and creative direction—developing narratives and platforms for a project to thrive in the long term. On Lucca’s website, there is a section announcing the things from which the studio is moving “toward” and “away.” She’s advocating for “Graceful Audacity,” “Scroll Subversion,” and “Logical Niche” rather than “Precious Notions,” “Self Serious[ness],” and “Drowning in Excess.” If you just silently said to yourself—yes, that’s absolutely what I want, but I wouldn’t have thought to phrase it like that—you’re sensing the keenness of Leigh’s talent. She makes evasive ideas feel obvious, concise. She filters out the noise of social media, makes you stop scrolling, and says, “Wait, I haven’t seen this before.” One of the keys to this, she says, is figuring out the nuanced corners of every project she takes on. Instead of focusing on the type of brand seeking out her assistance or the interests of their stereotypical audience, she’s curious about the ethos and originality of each project, which she believes will sustain it over time. “What excites me most is idiosyncrasy,” she says. “I love when a brand or designer approaches me with something completely off-the-wall, or brings references to the table that are totally unexpected rather than just listing off what their direct competitors do. Our work heavily emphasizes archival research, concept-driven creative direction, and in general, putting less, but better content into the world rather than just repeating the same boring stuff everyone has seen a million times. Be better!”

“The most fundamental truth for me has become doing what I love and not overthinking it too much. There’s a lot of freedom in realizing we can only create around what we connect with – if it resonates with others beyond that, it’s outside of my control. I find a lot of possibility in that mindset.”

Michael, similarly, is interested in the genre-shifting nature of Balmorhea, which he started in 2006 with his music partner Rob Lowe. “We had zero forethought of what we wanted it to become,” he says. “It grew slowly and steadily through the years doing everything ourselves and learning as we went. We drew influence in the early years from a mix of music, literature, and film informing narrative arcs. We’ve always borrowed lines and words from poetry and literature for most of our song titles. Early albums reference Adam Zagajewski, Seamus Heaney, and Paul Celan with later works drawing from Federico García Lorca, Daniel Boorstin, and Eliot Weinberger.” With each album, he and Rob have challenged themselves to, on the one hand, add new depth to their existing style, while also pushing the horizon of narrative and musical possibilities. Their sound is so cleanly their own, and yet, with each album, it evolves into something it has not been before. “When meeting someone new, if they ask what the music is like, I usually explain that it’s instrumental music based around piano, guitar, and strings. That it has some ties to film music, classical, Americana, folk, and some experimental aspects. It’s hard to pin down an exact genre … and that’s something I like about the music we make.”

The past few years have brought noticeable shifts in their careers. Balmorhea had taken a breather after recording and touring during 2018, and when they began the writing process again for what would eventually become The Wind, they understood in the writing process that “the body of work would be walking into some new waters and had a little more to say.” This new direction was aided by a friendship with Nils Frahm, with whom they’d toured previously. “We’d played a concert in the main hall at Funkhaus in 2018,” Michael says, “and got to see the Saal 3 studio after the show, which prompted us to make our record there … With our previous recordings revolving mainly around piano, guitar and strings, we were excited to explore some more territory with The Wind including brass, woodwinds, organs and some more overtly choral aspects.” The new record feels equally expansive and stylistically sharpened—it’s received enthusiastic early reviews since its release.

“My most visceral, sensorial memories come from some moments [growing up in San Diego]: eucalyptus, hiking cliffs on the edge of the beaches, the quality of light in the summertime, looking out the window of my parents’ car listening to Paul Simon’s Graceland on repeat. I think about those moments often, trying to rediscover that sort of weightlessness and dream-like quality I felt. I think subconsciously those are feelings I am somehow yearning for in my own work.”

Leigh has also stepped into a new professional space over the last few years, refining her work through Lucca and her other major creative project, the Moon Lists. “I got the initial idea for the Moon Lists project after I happened to come across an interview with a photographer named Sam Abell, a former National Geographic photographer who now lives in the Blue Ridge Mountains,” she says. “In the interview, he mentioned a personal ritual he shared with his wife, where every full moon they would ask each other the same set of questions to examine what had changed, stayed the same, or been thematically relevant in the last month. I was intrigued and wrote to him, wondering if I could learn more about his list of questions and for permission to repurpose the idea in my own way. Over a year later he wrote back—and I was captivated by how simple yet evocative the question-asking process became when it was bound by repetition and time.” This ritual is a helpful way to reflect on small shifts in one’s life, but it’s also a way to feel less alone, recognizing that everyone is steadily processing the large and quotidian issues of daily life. When trying to identify the components of one’s own inner landscape, Leigh acknowledges that people are often left without a map or compass. She saw this as an opportunity to examine the recent past in a new way. “I started sending out questions to different contributors every month,” she says, “but over time, I realized friends and strangers were using the series in a different way than I intended, allowing the questions to form prompts for personal reflection or conversation. A printed, guided workbook came from this, and since then the concept has evolved, today more broadly considering how lists as a device can be used to think differently.”

“Unearthing better ways to understand, recognize, and develop a vocabulary around the “you of now” is just way easier when you start with detail. The list is a very easy entry point for deeper thinking – ask a softball before you plunge into complexity. Oldest trick in the book!”

Similar to people-watching, reading other people’s lists or brief answers to questions is a form of eavesdropping without much context. Reading other people’s lists can be equally aspirational and cryptic. Even looking back at one’s old to-do lists, day planners, or goals can simultaneously engender nostalgia and a sense of foreignness towards one’s previous self. Lists are a way to corral the complexities of life into categories, and in this way, to make something ineffable take on a structure, a knowingness. “Lists by their format require one to think in specifics, which feels rare when conversations about the present are often summed up in broad strokes.” This is similar to a well-known concept in poetry: to talk about love, you must first talk about the smallest bit of dirt. One must stay with the dirt for as long as possible until meaning breaks through. In other words, the specific is universal—but the universal is too broad to register as specifically meaningful. “Unearthing better ways to understand, recognize, and develop a vocabulary around the ‘you of now’ is just way easier when you start with detail. The list is a very easy entry point for deeper thinking—ask a softball before you plunge into complexity. Oldest trick in the book!”

There’s a through-line of authenticity and allegiance to deeper knowledge that connects Leigh and Michael. It’s rare to meet a couple with such commitment to their independent goals, while maintaining a calm, shared enterprise as they build a thoughtful life together. There’s symmetry even in their differences, creating an energizing, confident loop. They wouldn’t say they’ve “arrived,” since finality is certainly not a concept they’re interested in, but they’ve found themselves in an evolved space, full of self- possessiveness and focus. “I’ve realized that nobody really cares or is watching all that closely,” Michael says, “I’ve become far less concerned with approval or affirmation. The most fundamental truth for me has become doing what I love and not overthinking it too much. There’s a lot of freedom in realizing we can only create around what we connect with—if it resonates with others beyond that, it’s outside of my control. I find a lot of possibility in that mindset.”

Leigh Patterson and Michael A. Muller are a creative couple living in Los Angeles, California whose work evades easy categories or monikers. Leigh runs Lucca, a creative studio that works with brands, individuals, and organizations on editorial and creative direction. She is also the founder of the Moon Lists, a guided workbook to inspire different ways of thinking about the present. Michael is a multi-instrumental musician and composer. He is the co-founder of the band Balmorhea, a genre-eluding classical duo with a worldwide audience. Balmorhea released its seventh studio album, The Wind, in April on the historic Deutsche Grammophon label. Michael has also released a solo project, Lower River, in 2019. In addition to all of this, Michael is a long-standing FF supporter and valued FF contributor. For more information, visit their websites and follow Michael and Leigh on Instagram. Or, to read more Friends of Friends stories about L.A.-based creative duos, check out this interview with the founders of LGS ceramics studio, or this profile of Caleb Lin and Christina Chou, the brains behind innovative menswear label Goodfight.

This story was co-published with Faculty Department, a personal journal focusing on the lives, spaces, and stories of creative individuals worldwide.