Gumtrees and Australian myrtles the size of small buildings lean in towards John Henry’s home: a glass walled greenhouse comprised of platforms, plants and an aesthetic smorgasbord of peculiar furnishings and iconic artwork.

John’s high ceiling and impressive window facade manage to offset the five levels of his home, the ‘Research House’, that he shares with his wife Deb Ganderton. John’s home is—amongst a myriad of other things—an impressively polished shed, a description intended only in complement. The ‘shed’ is an Australian icon: a place to store faded photographs and old trophies. A place to conduct whiny band practices and live out other dreamy, backyard aspirations. A place to round up a collection of old, worn out couches, host movie nights and crack open a couple of tins on a balmy summer evening. A place where life happens. “We have lots of Sunday lunches here with family and friends. That sort of thing,” John says as he sits in his dining room—or rather, his dining platform.

This portrait is part of Home Stories – a collaboration Freunde von Freunden produces with Siemens Home Appliances. To find out more about John’s home, see the portrait with him on the Home Stories site.

“I wanted a big, completely open space.”

John Henry

John Henry

To walk, drink, and wend one’s way through their space is fundamentally a social experience. “The general idea is that you move from one platform to another,” John explains. Arriving at the dining room, people are then able to migrate toward the kitchen, where John paints a picture of his enthusiastic wife behind the counter immersed in fragrant spices, heat, the dull sound of wine glasses clinking together, and laughter.

Conventional living structures only work to isolate experiences. Having lived in a classic, old-fashioned house in his youth—one built in the 1940s—John wanted to steer clear of totally enclosed spaces. “My parents weren’t really that social. In fact, they were very religious. My father was obsessed with working. They didn’t entertain a lot, [this home] is entirely different.” In fact, it’s almost inevitable for a home with no rooms to be, in some sense, communal. “I wanted a big, completely open space.”

Besides a designated laundry station—a small, black box measuredly camouflaged amongst John’s animated collection of furniture—the mathematical arrangement of platforms and staircases takes open plan living to a new, innovative level. “My wife said, ‘I need a laundry. I need somewhere to iron’. I said ‘Well, what about the cupboard upstairs?’ ‘No, I need a room,’ she said. That’s how the box came into being. To make it recede, we painted it black.” A mixture of strategically placed wardrobes, cupboards and other attractive storage facilities work to impressively mimic walls; granting privacy to necessary areas of the home, such as the bathroom and bedroom.

“I didn’t take up music ’til about ten years ago.”

John Henry

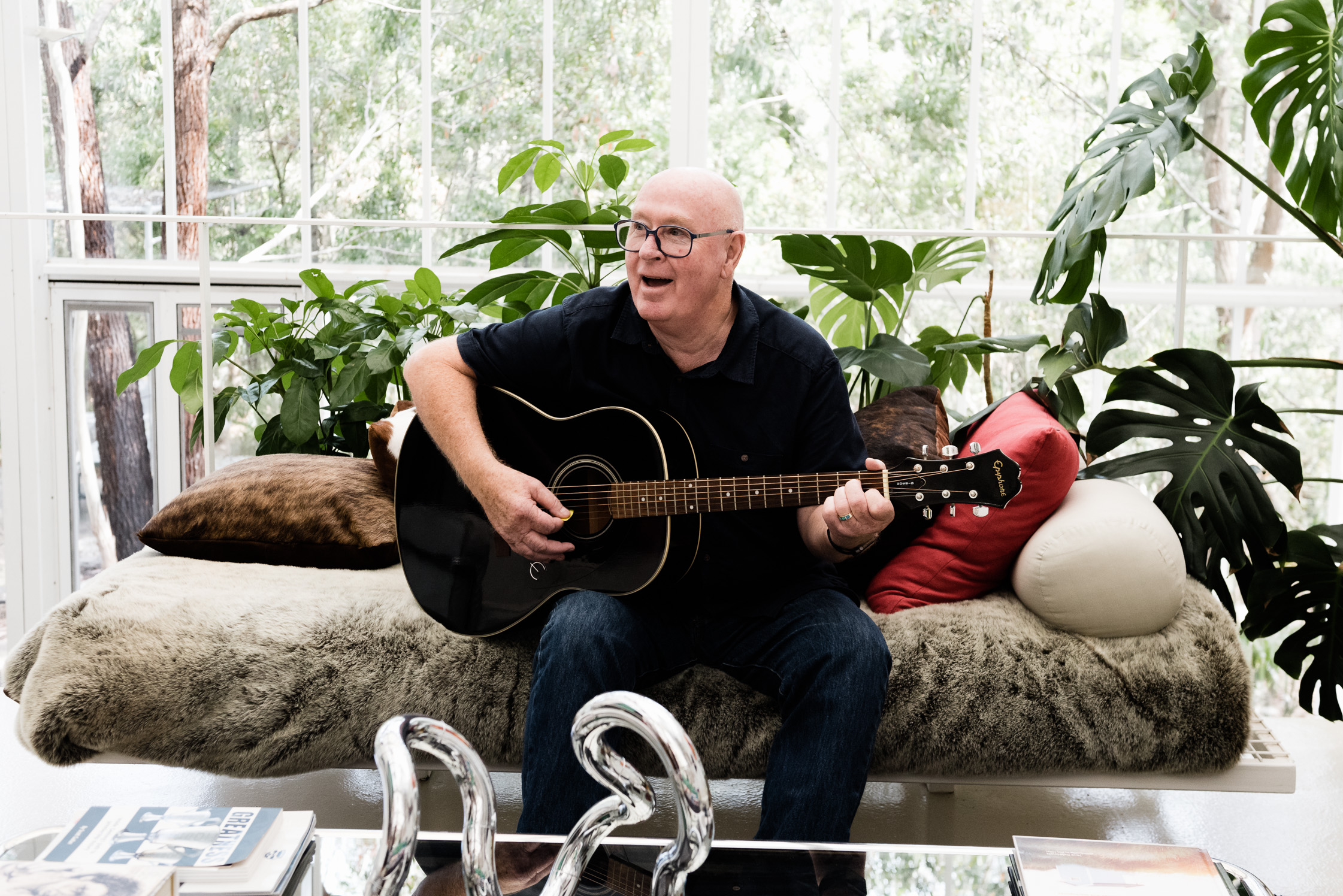

By his own admission, the platform John occupies the most is the ‘media room’: a relatively concealed area directly beneath the bedroom which sports an ambitious collection of musical instruments, books, tapes and DVDs. “I didn’t take up music ’til about ten years ago. Practice is the difficult thing. But it catches you. Once you’ve made the effort to sit down, you just can’t stop it.” In this particular level, John’s energy and curiosity to learn, explore and enjoy life to the fullest is largely preserved. “This is the ‘fun’ room”, John says, with a coy smile on his face.

He is a collector, but not explicitly of tangible items—from an outsider’s perspective, this may seem the be all and end all of the accumulation of fine art in general—rounding up valuable pieces of work and exhibiting them in one’s home, a private gallery, if you will. However, each canvas, or eclectic piece of furniture lives with John in virtue of it being intimately tied to a story. He, with the pride and joy of a spirited grandparent or mentor—both of which he has much experience in—provides his eclectic collection of iconography a home simply to honour them: to give them the opportunity to invite others in to consider their narrative, and listen to how they came into being.

“In the ’60s and ’70s, this would’ve been called the conversation area,” John says, as he steps down to another platform—patting the back of his Robert Venturi sofa: a cotton portrayal of Las Vegas bursting at the seams. In the artwork, fashion and furniture—all of which reveal, in their own way, a cross-generational display of political expression throughout the twentieth century—one can move through time. “He doesn’t like being called a post-modernist,” John laughs, when describing Robert Venturi. “When he designed this furniture range for Knoll, he tended to exaggerate items. Venturi modelled this couch on one of his staff’s grandmother’s couch, but exaggerated the arms to make them look more brutal and clumsy! I found this in Chicago” he affectionately explains.

If one were to make sense of John’s home on paper, it would—no doubt—seem chaotic. Rather than channelling one particular inspiration: be it an era, a color, a culture, or the like, John’s artistic influences are serendipitous and expansive. And yet, the atmosphere he has created is delightfully cohesive. Calming, even—and not just because of the waterfall formation that comes out from under the rocks in John’s indoor garden. “The water becomes annoying after a while,” John laughs. He impressively reflects upon the timeline of each item with an affectionate understanding and sympathy for its roots, its worthiness, and its unique story. From the Commes des Garçons garment draped over a mannequin—a memento for John and Deb’s love of Japan—to an original Jenny Kee duvet cover from the ’70s, and an eight-foot long vintage Women’s Weekly sign picked up from a Collingwood bazaar some years ago—each feature, with its distinctive and often comedic history, makes up John’s eclectic home.

“I continue to buy things,” John smiles. “My wife said, ‘John. I realised you had a habit. Now it’s a sickness!’” For John, as long as there are walls, the act of furnishing the Research House never ends. Each piece of furniture is, in essence, artwork. The process of developing his home mirrors that of a person cultivating a character. The house, for this reason, possesses a very real, very human personality. We are each made up of a myriad of experiences some conflicting, some unified, and some entirely random. John’s “obsession”, as he calls it, with quirky furniture was birthed in his young adulthood. “In the last three years [of architecture study], I did an elective of furniture design at RMIT University. I learnt how furniture was made; the impact of human stresses and forces on a chair, and how you have to [consider] that. I like chairs. All chairs are different. They form nice sculptures,” he states, as he signals toward the eccentric Frank Gehry ‘Red Beaver’ chair, a classic armchair made entirely out of cardboard. “You can sit in it,” he contends. “But it’s not desirable. It sits there as a piece of sculpture.”

The Research House stands alone as a visual passport: proof of an entire, eclectic lifetime as curated and conducted by John himself. From the Michael Graves’ collectables, to his own grandson’s signature written in crayon, preserved on an old envelope—“grandpa”, it reads—being held up by magnets on his fridge, the Research House solidifies John’s mark on the world, as well as how the world has left a lasting impression on John himself.

This portrait is part of Home Stories – a collaboration Freunde von Freunden produces with Siemens Home Appliances. Home Stories explores the topic of innovative urban living, seen through the lenses of select inhabitants in modern global cities. We present unusual spaces, highlighting their aesthetic and technological qualities, alongside a look into their inhabitants’ lives.

See more on the Siemens Home Appliances site and take a look at our other portraits in collaboration with Siemens Home here.

Photography: Andrew Kaineder