One morning in 1989, a few weeks after the Tiananmen Square protests, James sat down to consider a rather short list of exit strategies. He had to smuggle his paintings out of China.

Born in Pennsylvania, James Higginson followed his parents’ advice who “like all good parents, wanted me to have a comfortable life, close to the American ideal,” and went into sciences to train as a marine biologist. However, his creative urge, which had been slowly brewing until then, finally fomented a revolution against his career path, and sent him straight into night school at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. His penchant for color and ability to fuse patterns in a very singular manner, landed him a position as the set decorator for the popular TV show Pee-wee’s Playhouse. He was awarded an Emmy for the show’s characteristic set design, that familiar world of wonders where distasteful amalgam transforms into a tasteful whole as different stories unravel.

So how did he find himself in China being afraid of “disappearing”? During his collaboration with a traditional Chinese painter, the country’s sociopolitical situation was already in a volatile state, and James made himself a target as he participated in demonstrations and gave speeches about the freedom of expression. Eventually he decided to infiltrate his paintings inconspicuously with political messages using Chinese proverbs. Where you saw raw landscapes, the title served you something else. Studying human frailty is an inescapable topic for James. One of his most renowned series“Portraits of Violence” (2003) addresses the issues of violence endemic in our societies and how we act as passive or active perpetuators. Once again, he uses the theatrical element of staged photography — a firm believer in artificiality as a device to effectively draw in the viewer. Almost everything about James has a cinematic quality — from his work to the way he describes his life stories.

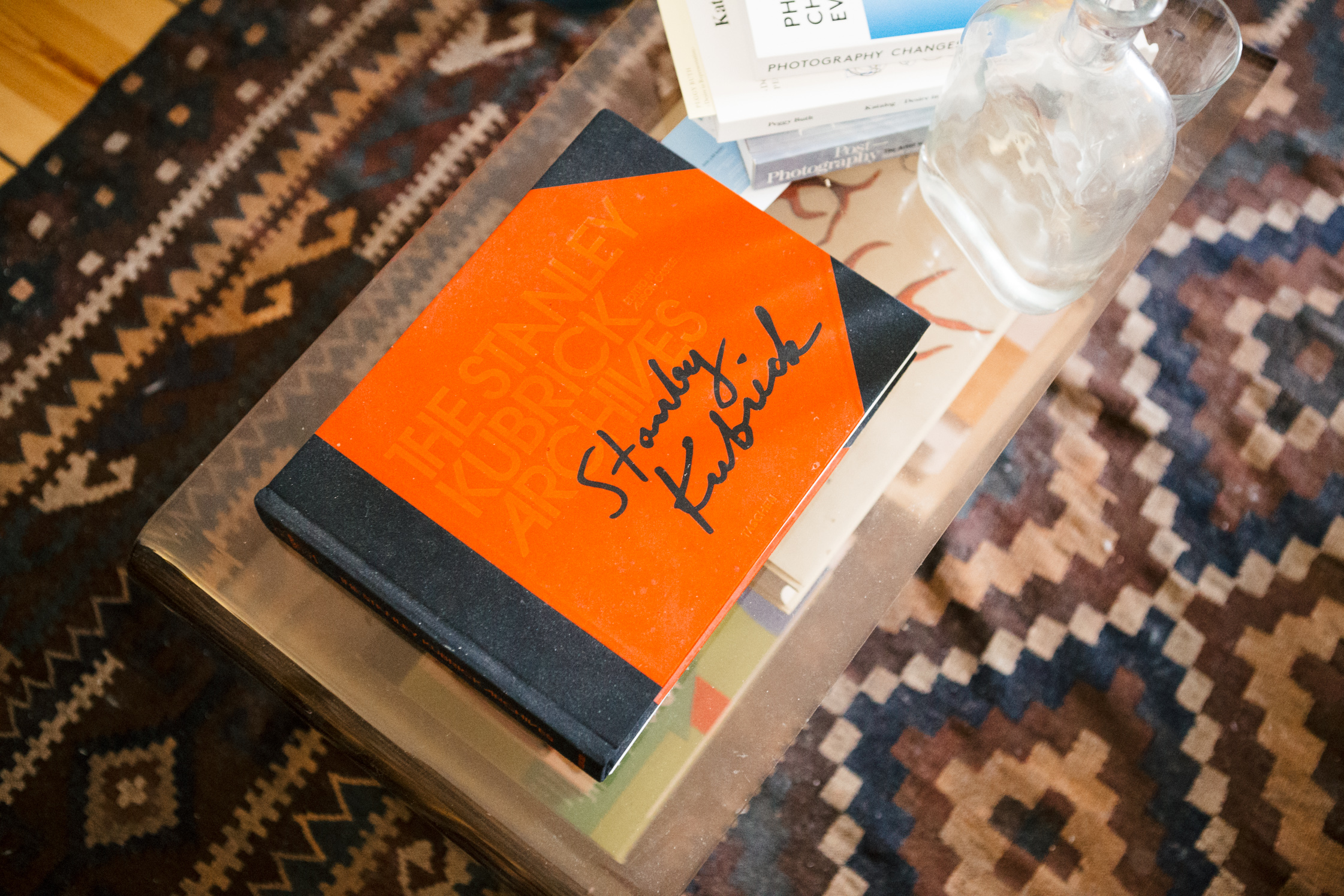

Upon entering his apartment, the first thing he shows us is one of the paintings he managed to salvage from China. On a white wall, rectangular pieces of wax paper assemble a large scene painted with aggressive strokes, showing a group of people in traditional attire. These faces must have seen the insides of quite a few suitcases packed and transported in agony. He tells us he’s in a perpetual state of being; constantly evolving, working across disciplines and assuming multiple viewpoints. James is indeed a man of numerous talents and with his wide, warm smile he seems unafraid of any hurdles tossed his way.

This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online, who presents a special curation of our pictures on ZEIT Magazin Online.

-

You were part of the creative team responsible for the set decoration of Pee-wee’s Playhouse. Tell me more about this stage of your career.

The set was just a sensation overload and that’s one of the aspects I loved about this project. I mean there were things like a six-foot diamond ring mixed with absurdly large can openers next to a wall shimmering of small little vinyl pieces. We mixed — good Lord! — we mixed so many different periods! This was a turning point in terms of set design. It kind of gave permission to create very eclectic and non-uniform sets.

It was actually a pivotal moment for set design on TV in Hollywood. There is a film called Pillow Talk where at the end of it an interior designer decided to retaliate against her deceiving suitor by decorating his house in a chaotic fashion – completely and utterly distasteful. Then you look at the set of Pee-wee’s Playhouse and this was done in an age of disrespect in art, if you want to call it that, where what was tasteless was going to become tasteful. We wanted to create taste out of distaste and we brought everything we could together to make a statement against pure minimalism and conformities. We were aiming for a very tasteless result executed in a very tasteful way. This quirky, strange juxtaposition was part of the fun.

-

Tell me about your trip to China.

I first traveled to China in 1988 and I was introduced to a Chinese master painter who invited me to collaborate with him. During that time I decided I wanted to look at the Tang dynasty and the modes of painting during that period since that was the last time China was free from any threat of invasion, so the arts and all cultural strata flourished. I returned to China in early June 1989, for our collaboration.

A few days after my arrival there was Tiananmen Square and, interested in sociopolitics as I was, I went to several demonstrations. The American government asked me to leave the country, but I decided against that since I had funded this project myself and it was simply a peaceful collaboration. The Chinese media jumped on us and we found ourselves at the center of attention. They tried to use our artistic collaboration to their benefit and basically say, “Forget about Tiananmen Square. Look at this peaceful artistic synergy between China and America.” I stood up and gave speeches about the freedom of expression but who knows how the translator that was given to me communicated what I said to the people. She was the daughter of a Chinese General and I was never left alone during those five weeks. There were only two nights when I was alone and I was very worried I was going to “disappear”. This thought first occurred to me when I was told I best not go to any of the demonstrations and I had better destroy my journal and photographs because they had taken some other Westerners captive. I said, “No, they’re not going to do anything, I’m American,” and they said, “At a time like this and in a country like China disappearances happen, and for your sake, you best take care.” My collaborator told me that during the historical cultural revolution he was sent to work at a farm for seven years as a punishment for painting Mao Zedong with a snake on his head.

It was scary for me too. I took the bullet and got rid of all my photographs, but not my journal. I came up with the idea that one third of our paintings should be more political and I borrowed Chinese proverbs for the titles. The titles dealt with what was going on in China. My collaborator never talked about it, he would only talk about the color of the painting, or the expression of the brush stroke — the very superficial nature of the work. Whereas I was focused on all the underlying messages. And this instilled in me the importance of using deflected images, metaphors, or devices to put messages across indirectly.

“After the Tiananmen Square protests I was worried I was going to ‘disappear.’ I was told I best not go to any demonstrations and I had better destroy my journal and photographs.”

-

I heard that you had to smuggle the work out of China when it was time to go. How did that happen?

Five weeks after the massacre at Tiananmen Square, the whole atmosphere had just become too uncomfortable. I needed to get out. We had drawn a lot of attention — it was time to go. I was planning to go to Beijing and then take the Silk Road to Pakistan. Instead, we found a businessman who traveled from Beijing to Hong Kong every week — same flight, same route and everyone at customs knew him. So they arranged that I would fly on the same flight with him back to Hong Kong and pack all the paintings into my suitcases. I was introduced to him at the airport, we sat together, and I cannot remember anything after that to be honest with you. We simply walked through customs without being checked and that was it.

-

What do you think of this whole story in retrospect?

I’ve written a metaphorical story about it where I created a character representing the individual that’s oppressed by the state. Once again, oppression has become an underriding theme through all of my work. I look and look to find the underdog, or I look to break through barriers of oppression. I talk with people and young kids coming out of China now and they don’t understand why the West feels that they’re being suppressed. They’ll tell you they have all the freedoms they want — they can shop, travel and go to school wherever they want. There are just certain regulations and restrictions they should abide by because it’s good for the country. I was stunned. “Our lives are fine. Our parents’ lives are wonderful, why would we want to fight against this?” It’s almost as if they’ve been bought into submission. And you look at Western societies and it’s somehow similar — we really don’t stand up or fight against real problems in our society, like domestic violence or violence in general. We’re really passive.

This is endemic inside our societies and it begins in the home. In my photographic series “Portraits of Violence” I looked at this issue. The family union is representative of the community, or the town, or the state. One of the portraits is called “Sacrifice” and is about a young man at war sitting on the lap of a general with his leg amputated. The young man’s brain is in a jar at the general’s side meaning that he’s given over his mind, his thought process and his whole being to protect his country. Without knowing any better, a young man going to war and fighting the war of old men for their business interests. It’s not in the face of freedom, it’s for business, let’s get real. This show opened the same week that the US went to war in Iraq and a very renowned art magazine editor came back and said, “At this time there’s no way we’re going to stand up and make any kind of anti-war or anti-gun statement. The business of war and guns in America is just too big to oppose.” I was just floored. Even in art this kind of attitude prevailed. It’s all business. If it’s not good for business we’re not going to rock the boat. I found it disheartening and disgusting, and it just really turned me. This area of focus is difficult as it upsets one of America’s largest businesses. Making guns for the consumption of war and violence.

-

Why do you use the device of staged photography?

In order to make people look at your work reflectively you have to have some sort of device, some type of a deflection. This idea goes back to the myth of Perseus and the Medusa. If you looked at the gorgon you turned to stone; if you look at images that are too blunt, you turn to stone. You have to find a strategy that will allow the viewer to see without seeing too directly. As Perseus looked into the shield of Athena to avoid turning into stone and cut the gorgon’s head, in staged photography we use theatrical elements to present a difficult topic in an aesthetic way that allows the audience to digest it. It’s almost a seductive tool to bring them in.

-

Is that why your work has obvious cinematic characteristics?

I was specifically looking at how violence is fed to the American masses in television and film. I wanted to showcase it as though it was the movie of the week.

-

The artificiality of it all remains in plain sight, you don’t try to hide it. Aesthetics are hyperbolized.

It’s all about this idea of the hyperreal and making everything more than it is. It’s a stylistic device that makes it okay to watch hundreds of people being blown up. That’s where Brecht’s idea of the epic theatre comes in. It’s this strategy of detachment and re-engagement. First you create a distance between the subject and the viewer, and then you try to pull them in through that device. That makes a good work of art. You see something from across the room that looks interesting and as you approach you discover more. Then the image is no longer just an image, it’s an experience that the viewers have with the work. It has a greater effect and it stays with them longer and on a deeper level. I present violence in the way we’re used to seeing it: in a glorified, often visually appealing way.

“We can say that we’ve been traversing the age of selfishness and indulgence for the last 20 years and we are now entering a new era of barbarism. This is the only way I can explain what is going on now. We’re entering a barbaric state of being where the state of things will be disrupted.”

-

Why do you think domestic violence is still a taboo, an issue kept under wraps?

I think because of the shame. But it’s just not right, we need to openly talk about it. It needs to be addressed along with America’s deep-rooted racism and love of guns. Allowing such violent acts to happen on that frequency is astounding and ridiculous. We’re wilfully blind to what we don’t want to see, and you’re either an active or a passive participant in the propagation of violence. It’s absurd that societies are so unashamedly shortsighted. People act as they have no care for anything other than themselves. It’s complete selfishness. We can say that we’ve been in this age of selfishness and indulgence for the last 20 years and we are now entering a new era of barbarism. I mean this is the only way I can explain what is going on now. We’re entering a barbaric state of being where the state of things will be disrupted and there are going to be revolts.

-

You’re looking at one of the topics that has preoccupied artists for centuries: the human condition. You mentioned human frailty in particular. What schools of thoughts have influenced your stance in this respect?

What really influenced me were the theorists Deleuze and Guattari, and the idea of nomadology. This idea of the nomad that moves between zones, between states of being like the solid, the liquid and the gas, or between the low desert and the high desert. It’s about this area of flux, positioning your work and yourself in a place where you can see more than one points of view. Nomadology has influenced me since the early days when I was still in formal training. This also lends itself to this idea of migration now it’s so much a part of the way the world has now been developed. Nothing is static anymore, we’re not raised in one community to stay there for the rest of our lives. We’re more mobile and more nomadic. I also take it metaphorically as being able to traverse media as well as subject matter. I certainly don’t have a problem with being described as a jack-of-all-trades.

-

There’s this duality in your practice. You go from heavily charged projects to conventionally beautiful images of unadulterated landscapes without any underlying messages. Is the latter type of work a mental cleanse for you?

I used to find recluse in the high deserts outside of Palm Springs and in Joshua Tree National Park. While wandering there, I intuitively felt that parts of the land were important, they felt like power centers. This land was walked by the Native Americans aeons ago. Whenever I felt a type connection, I’d look around and I would see a beautiful vista. For me that was a reconnection to the land. Looking back to the mid 1800s paintings and the poetry of Walt Whitman where simply being in nature was a beautiful subject. The bucolic dream. I don’t care that these are beautiful and that this attribute is something frowned upon in the art world. It’s a sort of reaction to everything being so cynical. This series touches on something more humanistic and pure. It is indeed a mental cleanse.

Nature and humans are part of a symbiotic relationship. Right there in nature I’m reminded that I am not just “being”, but I’m in motion towards something, and I’m always “becoming”, I’m always in a state of perpetual being.

It brings to mind the interconnectivity of all things. You look at the islands on the ocean and only see what’s above the surface of the water, and they all look disconnected to each other. But under the water each landform is a continuation of the next and all is connected. Same as there’s a complete interconnectivity between all landforms on Earth, there’s a complete interconnectivity between all living creatures alike. One affects the other, and if we don’t believe that then we’re crazy.

“Same as there’s a complete interconnectivity between all landforms on Earth, there’s a complete interconnectivity between all living creatures alike. One affects the other, and if we don’t believe that then we’re crazy.”

Thank you, James, for sharing your opinions and life stories with us.

Find out more about James’ work on his website. Read the rest of our interviews in Berlin and indulge in interesting discussions.

This portrait is part of our ongoing series with Vitra. Visit Vitra Magazine to find out more about James’ approach to interior decoration.

Interview: Effie Efthymiadi

Photography: HEJM