Outside of London, on the peaceful banks of the river Thames, photographer James Fisher has created a unique home and floating nook for himself that reflects his fervent longing for escape.

After traveling for four years, James found himself settling in a houseboat within a community of like-minded people living out their modern concept of nomadism on canals. Paradoxically, his restless life on a drifting home has grounded him more than anything else, as he finally belonged to a group where he could grow roots and connect with his surroundings.

Adhering to his personal approach, his photographic work reveals a profound fascination and curiosity for realness and tangible moments with a poetic tone. Both in his portraiture as well as series of cultural observations, he discovers communities and concepts of ingenuity that influence his attitude towards life. In conjunction with this, his work as an on-set photographer for major Hollywood productions has led him to further explore a different side to his photographic nature by embracing the more allegorical language often found in films.

During a visit at James’ fixed house followed by an afternoon boat trip, we discussed the differences between his two distinct creative identities, his interest in subcultures, societal microcosms and how a children’s book is possibly responsible for infiltrating his imagination with the notion of living on water.

This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who presents a special curation of our pictures on ZEIT Magazin Online.

-

When did you first get into photography?

Actually my grandfather was a talented photographer – he had a darkroom where he used to print his own images. As a kid, I was really fascinated with the idea of a secret room where no one was allowed to enter. To me, it was a magical place where an image would appear on paper. At the age of 14, I was in the darkroom myself using basic equipment. Photography was my hobby. When I was at university I started building my own darkroom. I spent a lot of time with a little group of friends who were also into photography. Two of them were working at a big commercial photography studio and one day they invited me down. I ended up getting a job as a cleaner and worked there for about a year. In between, I was using the studio’s darkroom which was much more advanced compared to mine at home, which was limited to black and white developing.

-

Do you remember the first picture you took?

That’s a really good question. No, but I remember that for my major high school art project I made a kind of illustration, a painting which was a portrait of a girl. That was the first serious piece of art l created.

-

Looking at your work, portraiture seems to play a major role. What is it that fascinates you about it?

I really admire pictures that have a shelf life. When I got into photography I was attracted to portraiture because it represented realness for me. It wasn’t about selling anything or a fashion fad that came out of people’s imagination. Portraiture can be anything – it doesn’t have to be a static shot of a person. In a sense, portraiture elevates an ordinary moment to something poetic: immortalized into a timeless object. Of course, there is a level of reproduction involved, as you have to recreate a certain moment. But in the end, the image itself originates from reality. As a photographer I am interested in the truth, I go into situations and observe things. It’s certainly not an uncreative process: In order to see what’s intriguing in that particular situation, you have to reach inside yourself, build up that moment and keep the essential elements to share with everyone else.

-

You’ve also worked as a film set photographer for several Hollywood productions where, in contrast to your approach, you had to cope with fictitious, imaginary scenarios. How did that happen?

I ended up in the movie industry thanks to the director Baz Luhrmann. He was making a movie in Australia – an epic 1940’s period film with incredible landscape shots. He was looking for a local who was familiar with the culture and scenery. At the time, I was just working on an art project which was a series of panoramic landscapes with some kind of symbolic drama. That was exactly what the movie aspired to do: use the landscape to tell an allegorical story.

I had never worked on a movie before. Studios usually go for someone well-experienced when it comes to on-set photography because an amateur could really disrupt the filmmaking process. However, Baz wanted the actual filmmaking to become part of the adventure and the creative process. What he generally does is putting people in unlikely positions in order to stimulate a certain dynamic on set. I think he chose me because he wanted to throw a little bit of a random element into the mix and see what happened. -

What is it like to shoot on a movie set?

It’s a really different situation. Normally photography is a very self-driven process. You have limited resources to tell a story but everything that you do is your own choice. You are the director. It involves a lot of self-reflection and questions about how to convey your idea. Working on a movie is nothing like that. The story comes from somewhere else. You have to apply your visual skills to that story and make it work as a still photograph.

Someone once said to me: “The art of working on film is about existing on set.” Everyone who is there gets in each other’s way because they all try to get their job done. As a photographer you have to be ready all the time and know exactly how to get a great shot in that line. I think diplomacy is probably a nice umbrella term to describe everyone’s attitude on set. You definitely need a tough skin and a good sense of humor. You have to connect with others to convince them that what you are doing is important and deserves its moment.

After enjoying a nice breakfast at James’ house we move on to his biggest love and protagonist, his boat.

-

You told me before that this is the most peaceful spot on the boat. Why is that?

The ship’s bow is where you come when you want to have peace. It’s the most quiet spot because you can’t hear the engines here. And it leads to this completely other world with all this open space you can find on the river. It is like the door to it.

-

What is this particular boat community like? And how does it appeal to your personal culture and way of living?

First of all, it is really diverse. On the one hand, you have very poor people seeking alternative solutions to minimize the cost of living in very cold and damp boats. And then on the other hand, you have very rich people with amazing boats which they only use once a week in summer. Somewhere in between, there is the sort of people like me that chose this as a lifestyle: Basically wanting unsettled lives and floating homes. Living on a boat means you are out there alone, moving all the time, unfixed and detached. It’s just the idea of freedom, isn’t it? Maybe we’re never truly free but just the idea of freedom makes us feel like we are. Last year, I bought a house at the riverside outside of London to have a place for the houseboat. Until last year, it was just me and the boat floating around London for four years. It was really different. And still, I live more on the boat rather than the house. This summer I want to go back into the city, forget about my house and just live on the boat.

-

How did you get this houseboat?

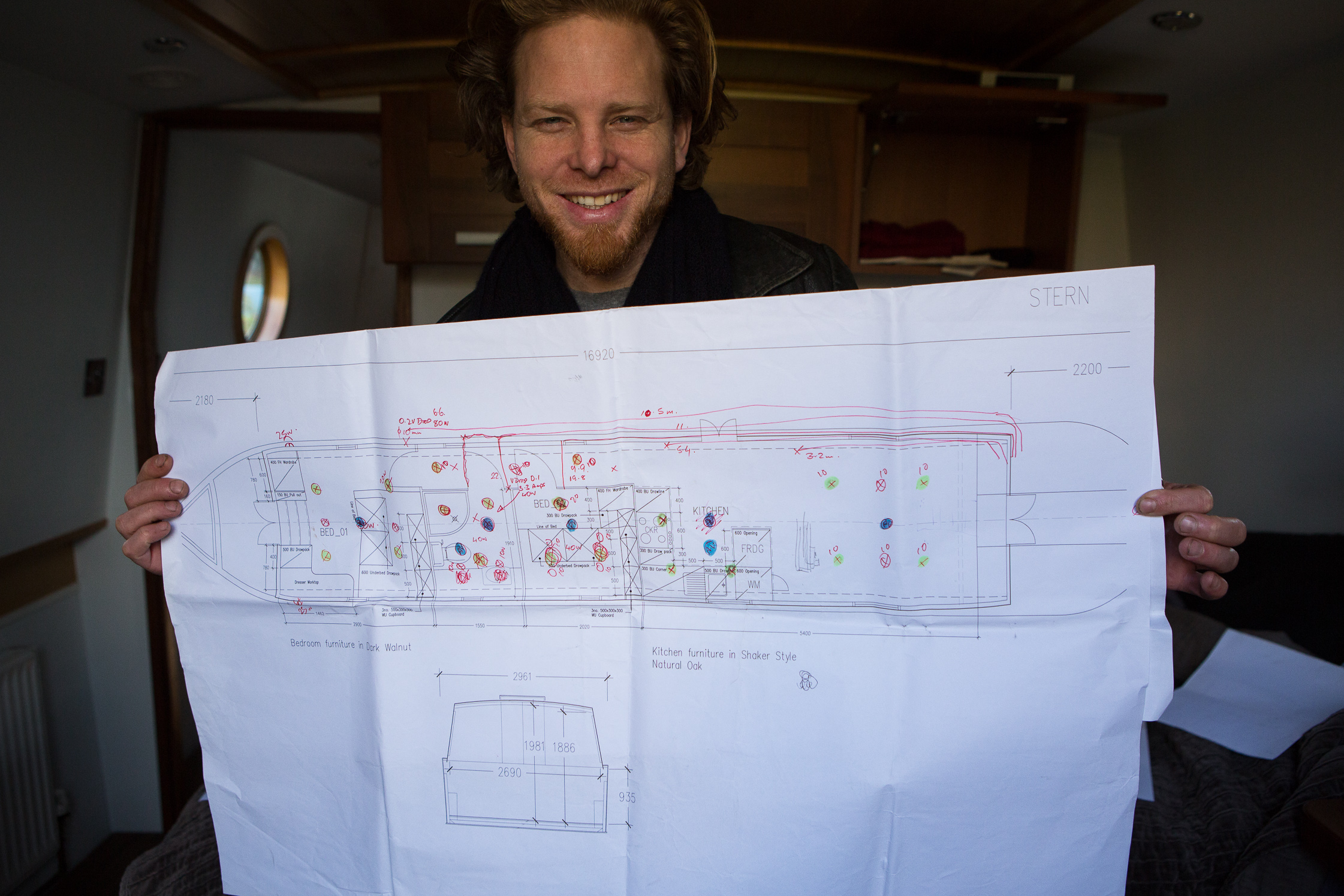

I used to live in a rental property at the canal in central London. After seeing all the boats, I started getting in touch with the people who owned them. Initially, the idea of getting my own boat was to get out of the rent trap in London. Either I could have watched my money disappear in rent over the next two years, or I could start a project to work on. So, I chose the latter. For the first year and a half, the boat was not in the water, just standing on blocks in a farm. The boat was purchased by a pair of brothers in the building trade from a traditional boat building company, who did the steelwork, engine and lined the boat with insulation and wooden battens. They built the basics of the interior but after five years the project stagnated and they wanted to offload it. I demolished parts of their work, and adapted the interior layout to my plan. Once I really got started I was completely taken with the idea of creating my own concept of housing.

The whole process was a mix of professional help and personal sweat. I designed and built most of it myself: the roof deck, kitchen and floor. Even the plumbing I did all by myself. I was only struggling whenever I would get someone in to do it for me. When it came to the electrics I was starting to pull my hair out, so I decided to work with a boat electrician. And of course, some things never got finished. For example, there is no bathroom door. I just could never work out where to put a bathroom door, so I put a curtain – which is fine because I just don’t invite people who have a problem with this. -

What has changed for you since you started living on a houseboat?

It really grounded me in belonging somewhere. I have been traveling and working on movies as well as other projects for four years. I was completely without roots and felt very unconnected to any community. Once I got into a boat and started navigating and learning the canal system – how to work with the weather and water – it felt like home. It became kind of a love, I guess. I always had a lot of friends and relationships from the boat community. Now, almost nothing I do is off water. Whether it’s the gym, supermarket or the pub: I just do things that are on the river. There is a whole new world to discover.

-

It’s interesting to consider that you were born and raised in a part of Australia far away from boats and water.

Right. I grew up in the countryside on a massive farm. A tiny town in the most hot, dry desert outback, 800 km from Sydney. When I was 18, I moved to Sydney and went to university to study an art degree combining psychology, philosophy and English literature.

-

What are you working on at the moment?

I’m working on a culinary travel book that focuses on traditional foodways from remote communities around the world. It will be something like a cultural documentary combined with regional cuisines.

-

Topics related to food and the respective industry have been capitalized over the past few years. What’s your personal take on that?

I think food is a universal language – it’s like music. Doors just open. If you come into a situation anywhere in the world and tell people that you want to learn about their food, you get invited to people’s homes and into their lives. But what is really happening is that people are sharing. Food is just the vehicle for sharing a greater story. All these different experiences made me become very interested in recipes, cooking, organic food, nutrition and even growing my own vegetables. I think the fact that people are becoming more aware of the environment is a cultural thing. Also, as you get older you realize how important it is to take care of your body.

-

What other projects are you working on?

The one that I am working on right now is a global portrait series with an architectural focus. It is about communities that have fallen off the bottom end of the economic system – about people who are building their own houses from whatever is available in their environment. It’s a form of urban sculpture in its most primary form. You can tell a lot about people by the way they create their homes. I have been doing research on various communities from around the world: from Pushkar and Radjasthan to a Bosnian gypsy family. It would also be fantastic to have a chapter on the UK floating canal culture, since I have great access to it. The next step is to make a short film as a kind of pilot for a global portrait series I have in mind. The film will be about homeless people in Tokyo – I really don’t like the use of the word “homeless” in this case as they are obviously not homeless but live in homes they made themselves. Tokyo is such an urban, high population environment that’s still home to this kind of outsiders living between concrete and filling the gaps. They build very beautiful houses out of blue plastic and discarded timber. The interiors are very particular, very Japanese.

-

In what way are these communities in Tokyo dissimilar to other communities you portray?

It’s not dissimilar. There are a lot of parallels between the different groups of people from around the world who live in makeshift homes. It’s actually a pretty interesting world because there is a whole other society that exists beyond economic existence and what’s defined by financial limitations. You can see it as a microcosm of modern societies – they have all the same different class structures and are not immune to the need for money. They have to compromise on everything and, above all, they have to depend on themselves, their own ingenuity and resourcefulness all the time. There is so much to learn from these people.

-

How do you relate to this mentality in particular?

In Australia we have a cultural tradition called “swagman” which is basically an itinerant hobo, very common in the era when people were adventuring out and establishing farms in the early 1800’s. They got around with a bedroll on their backs, a teapot billy and a dog. When I was a kid I used to look up to these guys because they were able to survive anywhere with their resourcefulness. As I traveled around the world, I discovered “swagmen” of every culture. When I see these people in Tokyo building their houses underneath bridges and between concrete gaps, I look up to them a lot.

-

Is this something that inspired or influenced your own concept of living?

Basically, its about totally owning your existence. I am very much inspired by the creativity and independence of these people. You undertake projects where you have to answer to yourself and somehow that is a much more purposeful approach because at the end of the day you are building and discovering yourself. Admittedly, with my houseboat I am doing it in a more expensive way. There might also be another reason why I ended up living on the water. Australians grow up with strong cultural references to England and mine come from a book called The Wind in the Willows. It was written by a fellow who was living on the river Thames and tells the adventures of little animal characters paddling around in boats. All is very richly described and atmospheric. Somehow, this image became very familiar to me. I grew up in the outback, so it’s strange that I developed a kind of relationship with the Thames. Then, suddenly I found myself there, in England, lying by the side of the Thames under a willow tree paddling around in a little boat and thinking: Oh my god, I have been completely brainwashed!

-

… what an intriguing twist of fate!

I joke about it all the time. When my mother visited I said: Look what you’ve done when you bought me that book.

James, thank you for this engaging discussion and for having us on your amazing houseboat!

We’re always intrigued by London‘s cultural diversity and great number of talented individuals paving their own way – you can meet more in our previous interviews.

Photography: Maya Roettger

Interview & Text: Marietta Auras