Hiroki Tsukuda is a contemporary artist based in Tokyo. Working as an artist is often not an easy way to live, however, this is especially so in Japan, where the category ‘art’ is handled in a very conservative manner. Hiroki’s career started as a graphic designer after graduating from Musashino Art University – around the time when we entered the millennium. He was one of the millions of graphic designers out there back then. One day he started to recognise the gap between how design work is processed, as opposed to how he wished to work and create. By chance, he met his gallerist today Nanzuka, and gradually shifted his position to the unknown world: from the graphic designer receiving orders from clients, to the artist who challenges to create something from zero.

His method of creations vary from painting, sculpture, drawing and collages – they are the collection of interpretations of his surroundings. His work is inspired by technology and the limitless information flow and diverse situations experienced in his hometown of Tokyo. Interested in “taking a peek into the parallel universe that exists on the other side of this world”, Hiroki’s work engages in an analysis and distortion of modern society. On this visit, Hiroki discusses his childhood in Kagawa on a small island called, Shikoku – famous for its udon noodles – and reflects on how his worldview has altered and expanded since he was young. He also talks about why Tokyo will always be his base despite his love of travel.

What have you been up to lately?

I’ve participated in a group show called “The Drake Equation” at Beams, Tokyo. The exhibition title refers to a mathematical equation used to estimate the number of detectable extraterrestrial civilizations in the Milky Way galaxy. I worked on this show with the German artist, Rene Spitzer, from Dusseldorf. He is constantly challenging himself, so seeing his work made me reflect on my recent works. Which, if I am honest with myself, I feel has become conservative, as if created only with the intention to sell. Lately, in order to open up new doors, I’ve been challenging myself and rethinking my works. I have been asking questions such as “where do my works belong in society” and “what are the implications of their existence?”.

What is your view of your home prefecture of Kagawa in the South of Japan?

Kagawa is the smallest prefecture in Japan and is on a small Island called Shikoku. It’s like a miniature world with a diverse mix of mountains, sea, flat lands and city areas. People there are all very peaceful except while behind the wheel! Local food is great too, especially the traditional udon noodles. Kagawa is known for the best tasting udon in the world and you’ll find an udon shop every 100 meters. Seventy percent of the people there eat udon for lunch, but due to its high glycemic index, Kagawa ranks number one in degenerative diseases in Japan in addition to the highest number of deaths by automobile accidents in the country. Art has become popular in Kagawa recently thanks to Naoshima; island hopping on a boat to visit art museums scattered around several tiny islands is a rarity in any country.

What was your childhood like growing up there?

As a child, surrounded by abundant nature, I was devoted to video games. You only start to appreciate its beauty once you’ve grown up and experienced city life. I always had a strong desire to travel to another realm outside of this world, even from a young age. It’s not that I hated reality and wanted to escape; it was more like I wanted to take a peek into the parallel universe that exists on the other side of this world. So when seeing a landscape or buildings, I always imagined that there was a spacecraft launching pad in the mountains or was convinced that the building was actually a secret research lab. A huge bridge boasting 12,300 meters in length called Seto-Ohashi was built when I was a child, and I remember vividly seeing it close up for the first time. I was blown away by the unbelievable size of its concrete mass. For me, it was absolutely an ancient ruin from another universe. So I doodled a bunch of stuff like that as a kid, like a cross-section of a mountain and a facility underneath it. When I went to the Chichu Museum designed by Tadao Ando in Naoshima, I felt that it was the exact manifestation of my childhood drawings – it was quite shocking.

Can you describe your life in Tokyo? What is a typical day for you there?

When I am creating large scale works, I go to my studio, but I don’t leave home when I am working on small stuff. When I start to miss people, I go out drinking with friends; if not, I soak in my bathtub and read, then watch a film or play video games before going to bed.

You were initially a graphic designer. What motivated you to become involved in fine art?

I started to question creating and revising things under someone else’s supervision. I wanted freedom to create whatever I wished and so started to make art. Clients define the meaning, the value and the intention of a design’s existence, therefore as a designer, you must always keep the recipient in mind while creating your work. However with art, you create all of that within yourself, not knowing how it is going to influence the viewer. I think I work better with the latter, and wanted to challenge this idea.

Which artists have influenced you the most?

In terms of painters, Max Ernst, Francis Bacon, Syd Mead, Hajime Sorayama, Frank Nitsche, Dirk Skreber and Tomoo Gokita have influenced me. I was also greatly influenced by architecture, films and music. But if I start a list, it would be endless, so let’s save it for the next time!

In recent years you`ve had a few events outside Japan, the solo exhibition in Berlin and in Amsterdam in 2011 for example, but is it important for you to keep Tokyo as your creative base?

I’ve been to many different cities in the world, but currently I am interested in Tokyo’s sense of speed. As I mentioned before, I grew up in a rural countryside. There was no internet then, so I was hungry for information. The books and CDs I wanted were not sold anywhere; the concert I wanted to go never came to our town. When I came to Tokyo at the age of eighteen, everything became accessible.

Kids growing up in the countryside nowadays can get all information online, so they’ve never experienced this type of information “hunger”. They don’t know the feeling of ecstasy; that moment you get nourished after being starved. I know this feeling of ecstasy. This is why I am still scared to leave Tokyo, although I do believe that it is one of the most difficult places for artists to live. On top of rent being more expensive than any other city in the world, few people really understand contemporary art. It is an extremely harsh environment for artists. Lately I’ve started to feel that searching for the meaning of art under such circumstances actually make it interesting. Perhaps this is why I am not leaving Tokyo now. Well, it’s really also because my English sucks, truth to be told.

How do you decide on your motifs and themes in your work?

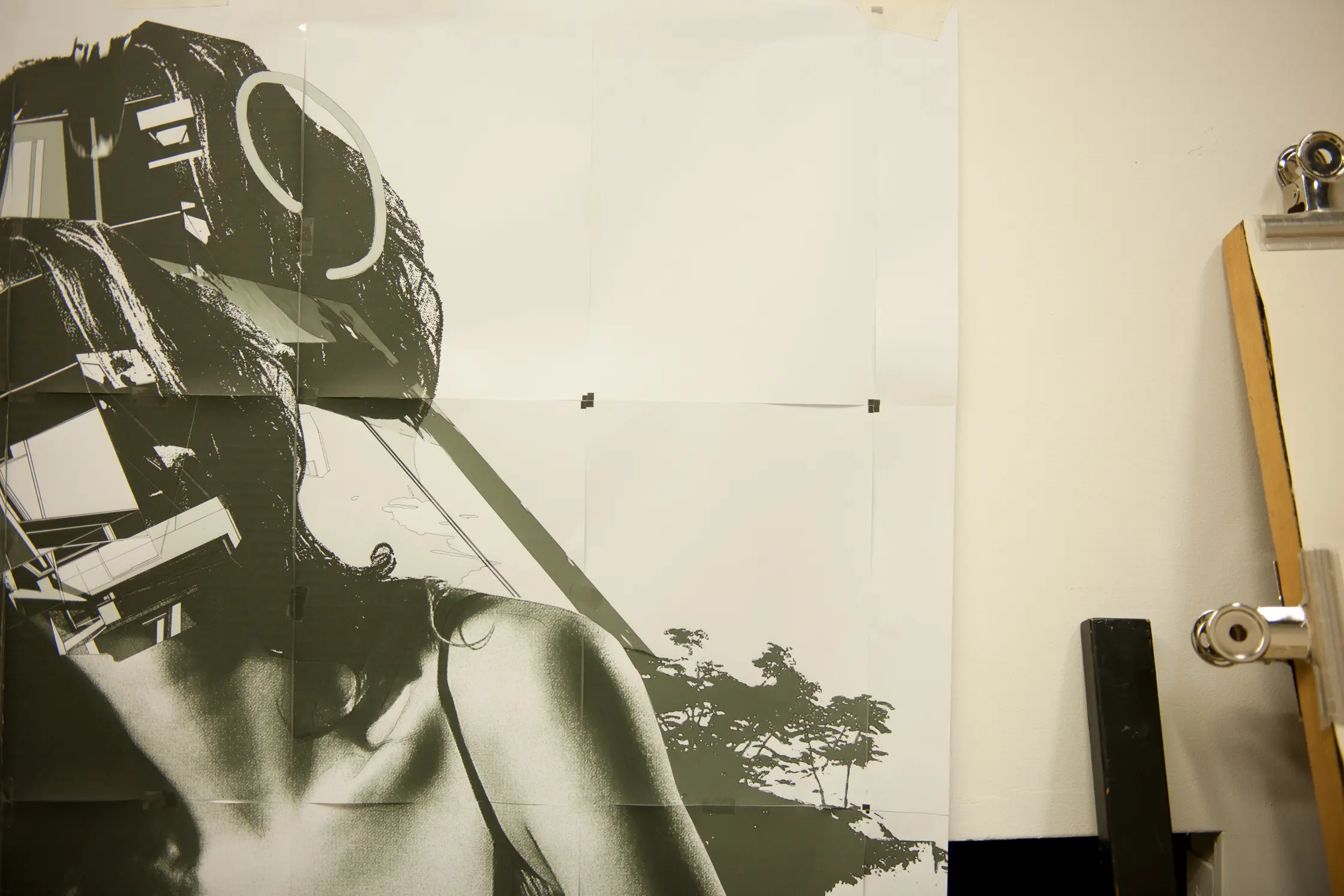

My universal theme, as mentioned earlier, is “to take a peek into the other side of the world”. I often choose motifs that are symbolically beautiful: beautiful landscapes, sculptures that are considered historically beautiful or sexy images that I find online. By transforming a part of this, a sense of awkwardness is created, as well as an indication or a sign, that broadly speaking creates a feeling of being abducted into another world or to an expanding parallel universe for the viewer. I create my work as an instrument to connect our daily lives to another world. And by peeping back into our world from the other side, a realization of distortion towards modern society is created. This is what I want to achieve with my work.

Is there a distinct difference in the interpretation of your work in Japan and elsewhere?

In Japan people do not regard my work as typically Japanese. On the other hand, people abroad think it is very Japanese. So as an artist I exist like a bat; not an animal, not a bird.

Is there a place you’ve never been to but definitely want to go before you die?

Yes, the Sahara Marathon! I saw it on TV the other day – it’s a one week race in the Sahara desert. It’s not just about being the fastest runner. Participants bring their own goals and determinations into this race; they keep running in this landscape where red sand and deep blue sky meet to define the sharp horizon. This was really moving – the runners who completed it broke down in tears from overwhelming emotions. This, I felt, was beautiful as human beings. I would love to take part in it one day.

Tell us about your plans for this year.

For the last two years I traveled abroad extensively, so I would like to go to places I’ve never visited in Japan. I also want to continue to bring a higher level of quality to my work.

Hiroki, many thanks for your time and talking about your life and work in Japan.To find out more about Hiroki’s artwork, visit the Nanzuka Gallery website here, or in Japanese, his personal website here.

Interview & Text: Akiko Watanabe

Translated by: Rei Matsuoka

Photography: Masanori Ikeda