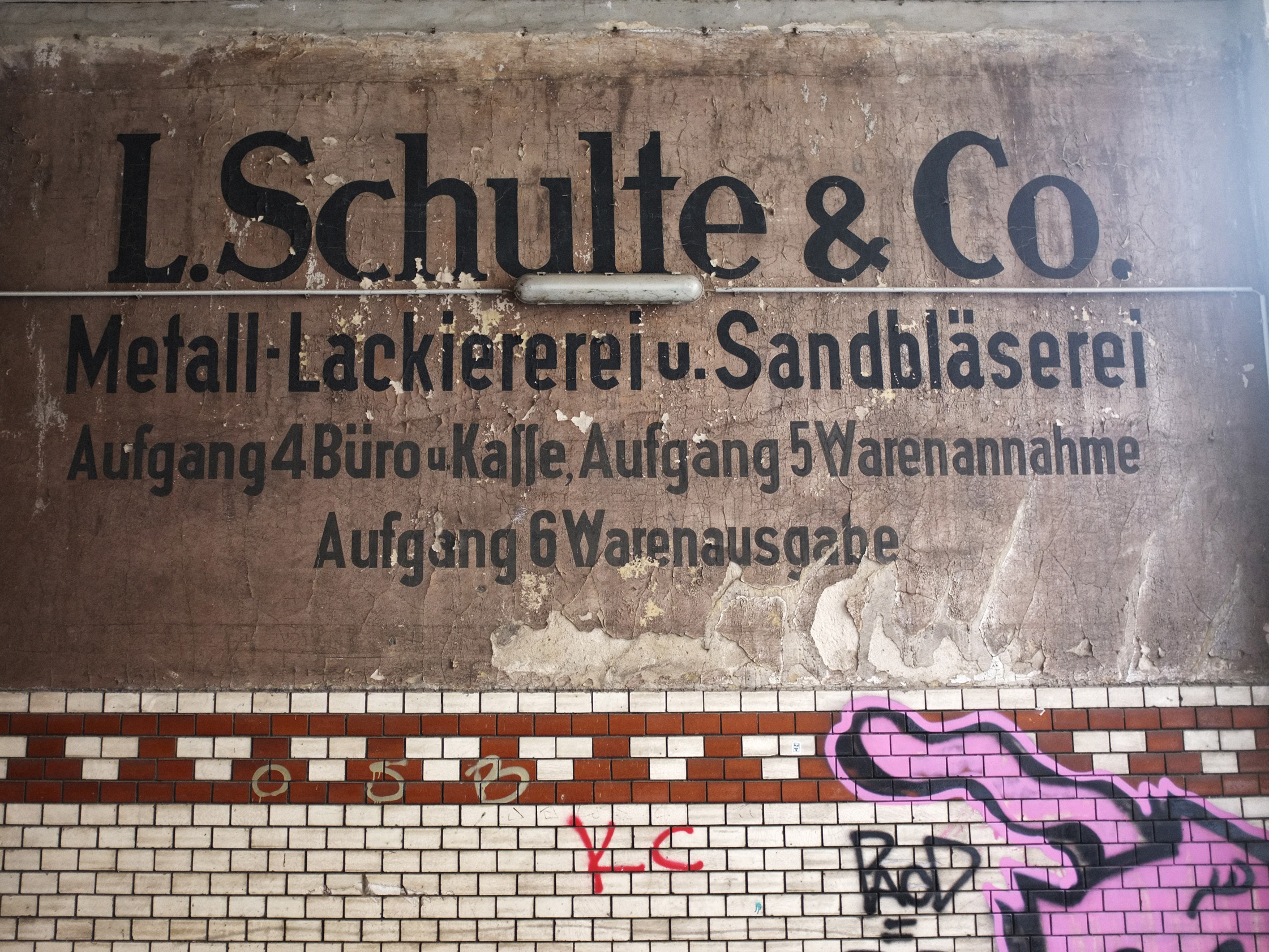

The house located in the middle of Gerichtstraße is one of those places that has the history of its brickwork still written within its very stones. There are no signs of time having bestowed it with rejuvenescence, while simultaneously the same disquiet sound is still caught among certain corners of this debilitated, exhaustingly seeming industrial castle.

One would not imagine that in the same courtyard, where currently an old Opel Corsa is being given a new cooler and while quietly Metropol FM is playing, a portion of WWII’s wreckage finds its rest. Only one yard further, one is being greeted by the harsh tonality of Steve Jones’ guitar chord, and long-haired men in overwhelming jeans gear. Leisurely, they all turn their sausages on a modest grill while opening one beer bottle after another – No, this is nothing customary. But it is Father’s day.

This is how it must have felt in Berlin’s occupied days, during which every one would find a little place to live and be able to think freely at. It is the same shelter that the contemporary, youthful crowd intends to find, who presume satisfaction in terms of a third-floor, renovated flat in the heart of Neukölln.

The monumental but unprepossessing façade does not exhibit the immediate, colossal area that realistically consists of an overall seven yards and brings forth the impression of being cast away on an island that drags itself all the way to the canal.

Fritz is one of this place’s dwellers, who managed to find both a life and a profession within these stale walls. The young man grew up in the protected South of Berlin and was, inevitably after his high school graduation, drawn to the perhaps more exciting edges and specifically none other than the Wedding neighborhood. This decision was not only grounded within practical reasoning, such as being cheap and near to his university campus Weißensee: “A West-Berliner will always be a West-Berliner, I don’t need fancy bars right at my door-step, I can always travel there…”

There was a moment in which he floated between studying photography in Leipzig or learning the craft of sculpture in Berlin. Essentially he decided to go for sculpture, “which offers naturally much more diversity.” Even though he never really kept in mind the notion of limitations within the study field, Fritz was able to enjoy a very liberal, creatively scholastic life at Weißensee and grow in terms of his interdisciplinary thinking and work. This particular manner of thought would soon imprint his career as an artist and be realized within his aesthetic oeuvre – his installations and sculptures, as well as his experimental photographs are leisurely rising with momentum to a concrete surface.

During his studies, Fritz unexpectedly inherits an entire goldsmith equipment, and instead of leaving it to rest and simply hold on to it as a dear memory of someone, he decides to take it into hand and give it back its true calling – to create jewelry. His affinity to design only supports and strengthens this doing. Even if Fritz often works conceptually, a substantial bond in regards to craft has been brought to existence: “Sometimes one must literally formulate things and built them, thus only remaining on medium like paper will never be enough. It doesn’t matter whether one works with wood, metal or horn. The fundamental idea stays the same.” And with this idea, Fritz tries to work out his very first concept of glasses.

Fritz is leaded by the conviction that every individual is able to succeed in one’s set accomplishments, “One must only be aware of the desire and goal.” The most important thing is to choose a certain path in order to achieve this goal and simultaneously built a network with friends and strangers who will stand by your side.

This philosophy is not only embodied in the sculptor, but also in the four walls he resides. Besides the given atmosphere of a fading industrial charm and an untamed, resistant nature, the sense of morbidity does not live here. If one is able to rely on others and vice versa, the rooms and infrastructure are allowed to awaken.

Two years ago, when Fritz moved into the atelier, the single room sparsely spared the luxury of a sewage and fresh water pipe. Electricity was provided for four months by a kind neighbor who connected an extension cable that essentially winded up in yet another neighbor’s flat. This is how the house stands strong, with the employees of the autoshop, a welder, a plumber business, some film people, and, “thank God not so many artists yet.”

At this present day, one cannot see most of the rough conditions and can only assume what it used to be like. The seemingly archaic tools, that are dispersed all over the rectangular room, provide the sense of a fallen time and seem to subsist as beautiful objects rather than actual instruments for the pursued jewelry profession.

The long table immediately invites to linger along, much like his owner, Fritz, who seems to be nothing else but comfortable in the temporary guest role while he offers us Cava, Wine, and coffee.

The light carefully dances and shines through a white, punctuated curtain, which was made out of snow camouflage gown from the Swedish army. At the other side of the room, a cube is located, which regardless of its colossal size of 4 1/2 qm, still seems indispensable and is swallowed unwillingly in the surrounding scenery. The concept comes from an architect, a friend of his. Fritz got the wooden pieces to be customized and then, just like a 3D puzzle, mounted the fleeting home together. One will find a bathroom in its very insides, a humble kitchen located around the periphery, and resting on top of it, a generous bed: “I think of this big room as a working space, but I live among my work, which most people don’t have to notice.”

And there you have it once again, the typical Berliner apathy that appears within so many of Fritz’s peculiarities – perhaps it is encountered in his immunity in regards to stereotypes or artistic limits, his appreciation of history or his demureness, which overall can be simply described as owning the necessary and rare charisma.

For more Information about Fritz’s broad artistic work take a look here.

Text: Antonia Märzhäuser

Photography: Anna Rose

Translation: Lara Konrad