In Beirut’s vibrant and varying districts wind caresses carpets hung out to dry, children play in the street, and elders drink tea under the Eastern sun. In this environment alongside abandoned buildings, crowded streets and a mix of cultural backgrounds, confusing, chaotic and beauteous moments are simultaneously stimulated.

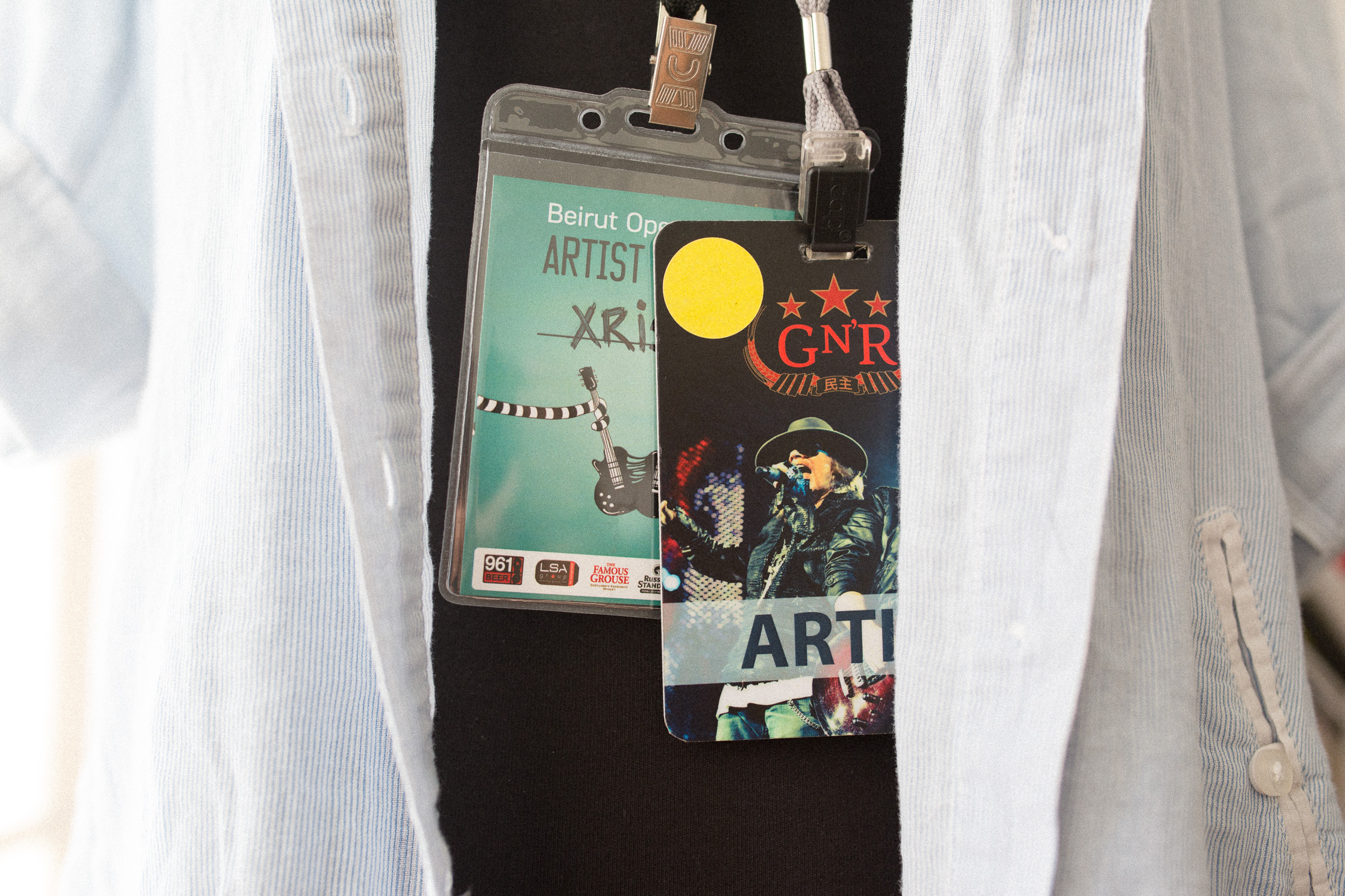

It is here that the musical duo, The Wanton Bishops – Eddy Ghossein and Nader Mansour – emerged in 2011. Before their internationally recognised music careers, Eddy and Nader were orbiting in different worlds: Eddy was a financial auditor, and Nader studied finance engineering in Paris. Thanks to the powers that be, these former finance professionals got lost in the pervasive sound of harmonica and guitar blues riffs, never to look back. In the blink of an eye the band was appointed the opening act of Guns n’ Roses in Lebanon’s capital, and have since toured throughout Turkey, France and Norway. Their music is as sincere as it is wild, conveying deep emotions, just like their hometown.

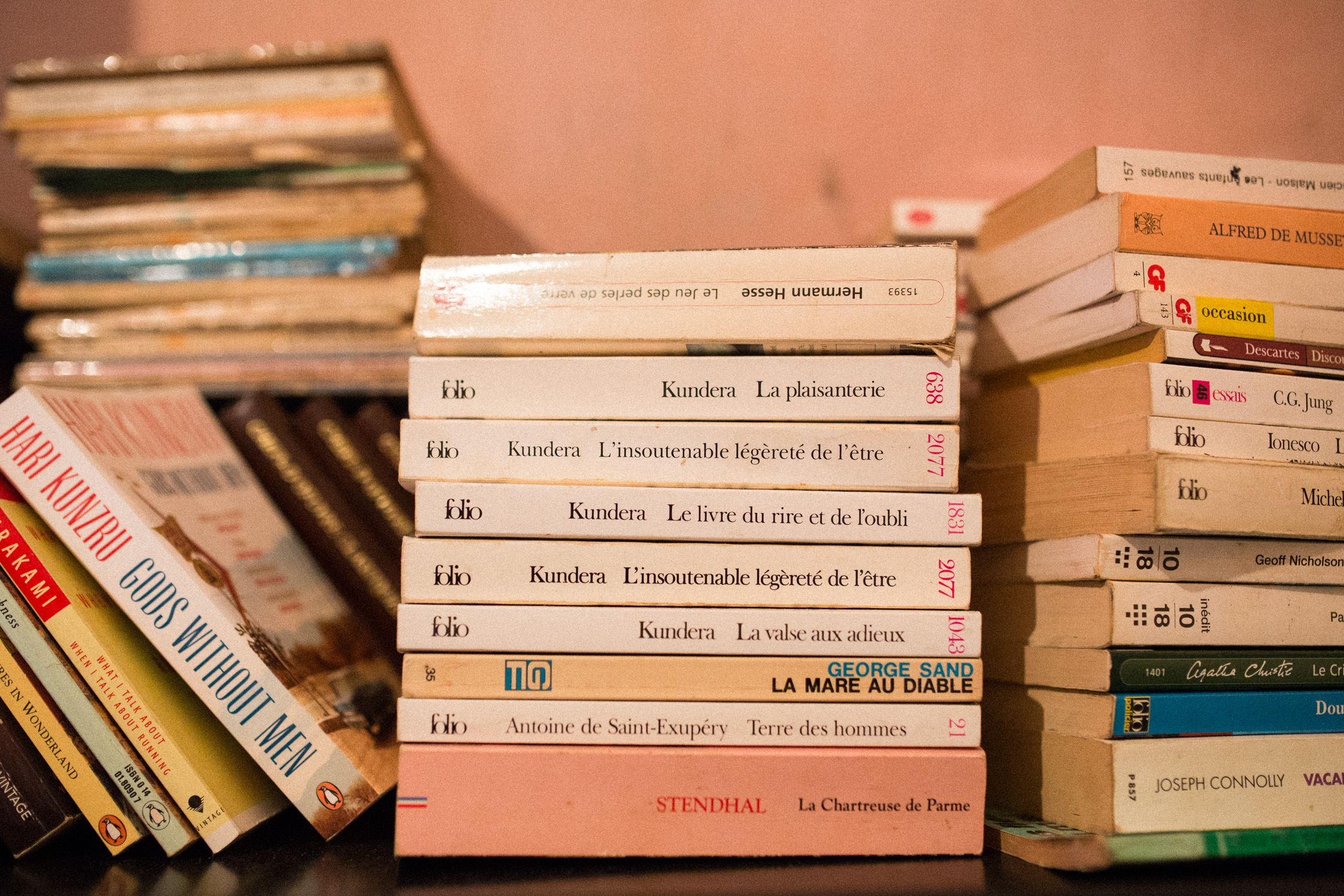

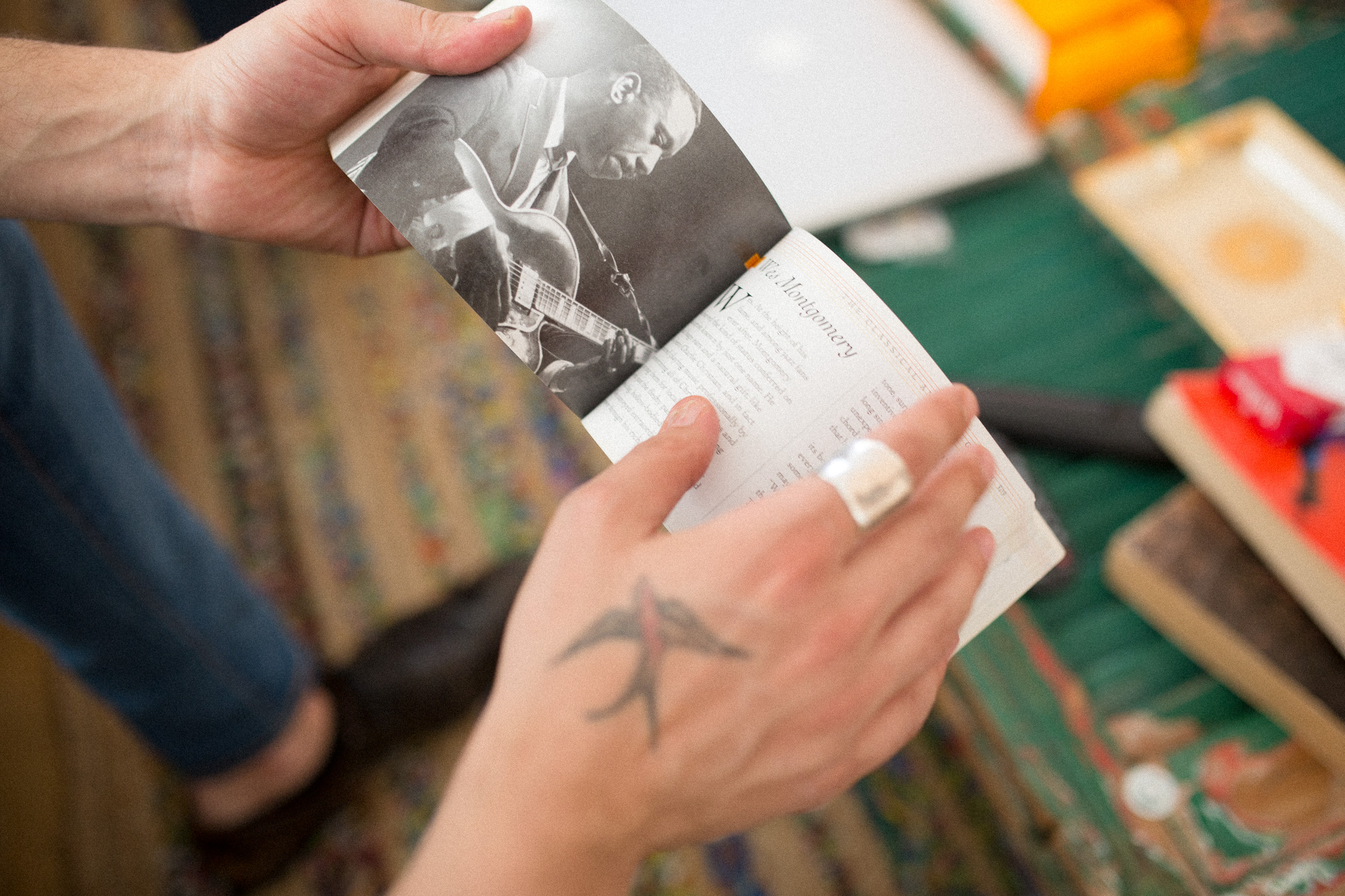

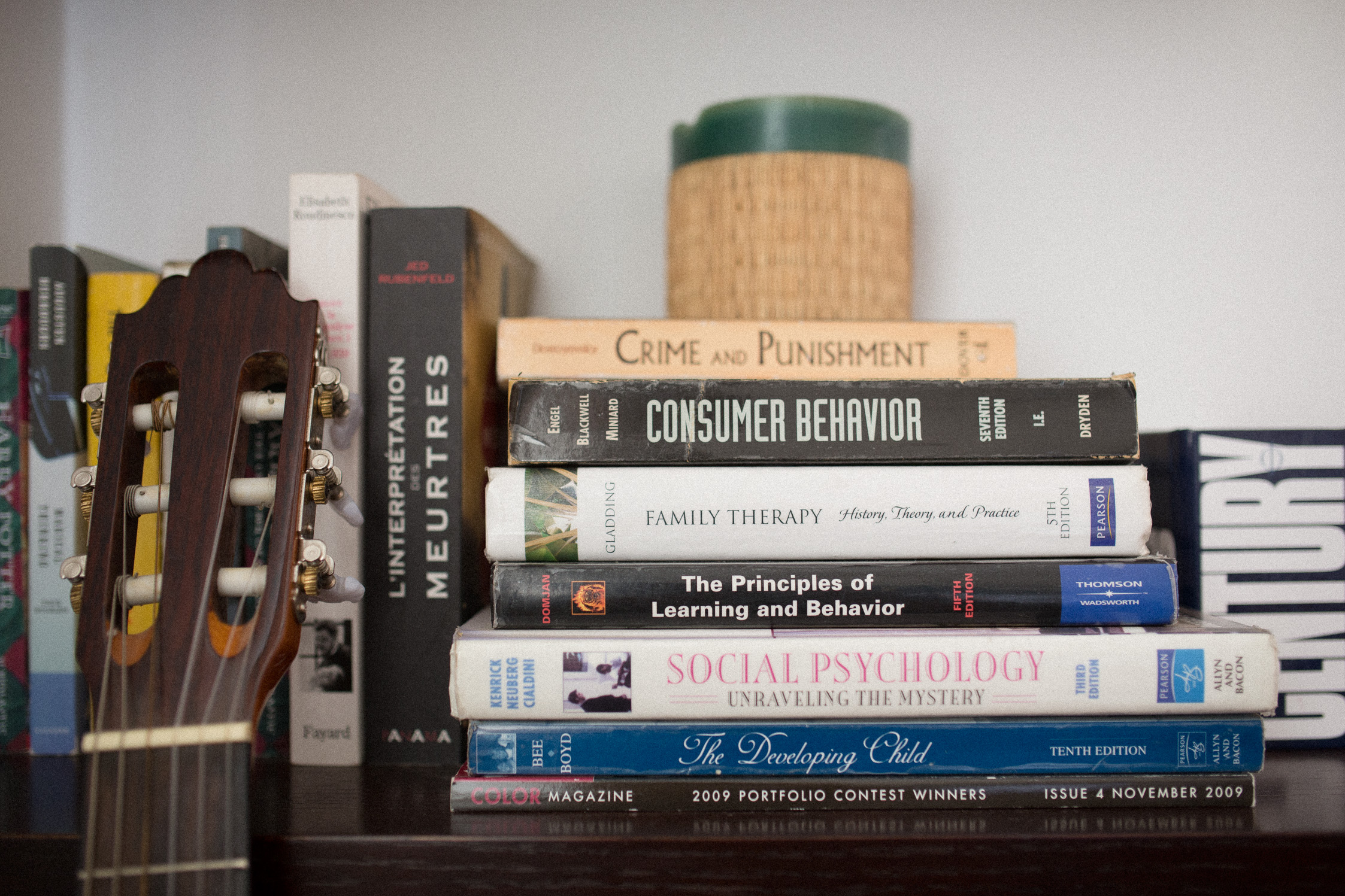

Nader – who sports a distinctive look with a full grown beard and tattoos on each arm – and Eddy started the interview at Torino Express in Gemmayzeh. The boys then walked to Eddy and his girlfriend’s calm light filled apartment on the hill of Achrafieh followed by a stop at Nader’s home and sanctuary that he shares with a friend in the bustling district of Mar Mikhael. Here they discussed how pain and little bit of craziness play a role in being creative, and the dramatic changes that have taken place in Beirut in recent years.

Where did you grow up?

Eddy: I grew up in Beirut. It is where all my childhood memories come from.

Nader: I grew up in the mountains just outside of Beirut in Zahlé.

What kind of surrounds do you need in order to create, and how does Beirut inspire you?

Nader: I need to be fed up with the city and go out to the mountains. That is where I write the most. I am like a sponge in the city, and then I go and squeeze it all out in the mountains. That’s my way of doing things. We have everything that we need here. The sun is important to me also, I loving having all four seasons. You can get frustrated with Beirut. It is dividing, you can be neurotic or really happy in this city all at the same time; a bundle of emotions that is very necessary.

Eddy: Actually the most inspiring thing when you write music is an emotion that is stronger than a regular state of mind: something that makes you crazy. It might be a car accident, a relationship breakup, or a death in the family; or even something very small like meeting someone at the bar that would inspire something. Concerning Beirut, it is our home. I feel really comfortable here in Beirut. The best day for me to be creative is when I return home at night, at 1 or 2am in the morning. I like driving in the car without traffic. It’s quiet, not cold and not warm. In these moments I can process things that I have seen and think about my emotions. I feel focused somehow.

Why did you suggest to meet at the bar Torino Express?

Nader: We had our first ever gig here.

Eddy: We put the amps on the tables and played four songs. We had a very small drum kit near the chairs. It was really weird. We had to play live somewhere, it was like a prelaunch. This bar makes us feel comfortable. We have been meeting here for the past three years to chill, talk and have fun. The bartenders are our friends, all the people we know come to this bar. It’s like a second home.

Nader: It was almost strategic to play here as a first gig as nobody knew about the band, or who we were. If you go and play in a big venue who would show up? It was like a surprise. It was a good way to let the word out and it worked. The next gig was full.

Eddy you play the guitar as if in a shamanic trance, while Nader, your voice convincingly summons the heartfelt ups and downs of the blues. While on stage you both seemingly flirt with the audience while performing. Are you aware of this or is it just a case of spontaneous improvisation?

Nader: What is good about blues is that it is music that is alive so it depends on the night. It is a free music. You pick up vibrations from people, yourself, and your instrument. You get into a certain mood and you tend to do things on stage that you haven’t done the night before. We do have some songs that are structured and have a start and an end, but most of the songs are quite free and open to experimentation.

Eddy: Sometimes we try some stuff on the stage just for the sake of it.

Do you have a fear of anything in relation to your music?

Nader: Fear is a strong word. We fought the world for this. We fought the lack of support of what we do. The only fear would be to have a fear of ourselves. That would be scary. It can ruin your music.

Eddy: We have fears of course. Like fears of things that would slow you down. Like an accident or maybe a war in Beirut, a block at the airport or missing a tour. However, they are not real fears actually.

Does politics affect your daily life in Beirut? Are you political with your music?

Nader: That’s two different questions. It does affect our lives inevitably.

Eddy: Even without us knowing.

Nader: But you learn to survive things and to navigate around them; to live in your own bubble. That is the only way to do it. It is sometimes double the amount of work to get a visa to go and play a simple gig which any musician in the world can do. But it makes you want it more.

Eddy: Everyone in Beirut finds a way to get things done no matter what. If there is no electricity or no running water we find a way. We never talk about politics. I really don’t know what Nader thinks about the things going on in Beirut in a detailed way.

Even though there are physical and visual segregation and sectarianism, Beirut is truly a city of encounters. It is a city that has developed from a no man’s land to an internationally vibrant center. Can you elaborate on this progress and development?

Nader: It is a good paradox. Of course sectarianism can never be healthy. Emotionally, it is a weird paradox. If you are clever or sensitive enough you can feel awful, but at the same time you can transform this weirdness into something beautiful. Or you can take a gun and shoot at other people. You have the choice.

Eddy: Like every country in the world there are communities that live in different places. Even if you don’t see it, it is there.

Nader: It is a very valid point. People think it is only Beirut, because that is what is on the news, however, it is possible to see this around the world.

Eddy: Actually I can go anywhere in Beirut and be with everyone.

Nader: If you are respectful to everybody…

Eddy: Of course there is a process of change. It is slow but it is there. Look at Hamra for example: 25 years ago it was impossible for a guy like me to go and get a drink there. Even four or five years after the war it was like a warzone. But a year ago I was living there, and now I go and get a drink there regularly. A lot of people from all religions come to Gemmayzeh to drink, play music and go to parties. Things are changing for the better.

So your experience of Beirut today is a very different one?

Eddy: Yes, but especially so as I used to work as a banker. I also became a salesman for medical and dental equipments at different stages. Whenever I went to meetings with doctors, hospitals or to bank premises, Beirut seemed different considering the stage of my life. Now I’m a full time musician with The Wanton Bishops. Sometimes at night I go for a drink to the same building where I once had a meeting in a doctor’s office, upstairs. Today, I see things in a really different way. Every corner of Beirut sparks a different memory. I have many perspectives of Beirut.

Eddy, How would you describe your neighborhood of Achrafieh to a person who knows nothing about the city?

Eddy: Beirut is kind of flat and Achrafieh is the only hill. So we are at the top of the capital. It feels like being the king of the castle and it is close to everything. My girlfriend and her sister moved to the area previously when I was living in Hamra and I decided to make the move.

Gentrification of any city always brings with it positive as well as negative consequences. Do you think this is also true for Beirut?

Nader: The negative aspects are there. A lot of old traditional buildings were torn down and replaced with skyscrapers and offices. The good side would be the charming nightlife that now exists. The bar culture is much better than the club life; like the bistro or the café where you can actually talk at night. One of the benefits of such gentrification is that it has attracted a lot of younger people.

Something that people may not know is that the sidewalks in Beirut are too dangerous to use. Essentially the city doesn’t allow one to walk through it. Do you consider this a problem or do you feel like it creates an atmosphere in the city?

Eddy: We barely walk in Beirut. That is a shame. When you live with something wrong for a long time you get used to it and at some point you don’t see it as a problem.

Nader: As a matter of fact it is a Lebanese characteristic: we can live with something being wrong in our lives for eternity. The walking problem is not really so crucial to our lifestyles. On the other hand one cannot bike in this city. I rode a bike one day and I gave up, I will never touch it again.

Nader, you studied in Paris – what brought you back to Lebanon?

Nader: Mainly Paris itself. Paris brought me back here. It was hard. I was doing something that I didn’t like. Paris is a tough city and a dark place sometimes. You cannot see much of the city except your neighborhood. You go out from the house, to the underground, to your work or school then come back and don’t see the beauty of the city. Damn, I was genuinely living underground! I rediscovered Paris this month on tour however. We had the luxury of having a car and is was a different experience.

What were some of the changes you recognized immediately when you returned?

Nader: Technically I haven’t lived in Beirut before I left Lebanon. I completed my studies up in the mountains. I’m a mountain boy. I knew Beirut as the place where we went to party. So, when I came back, I discovered it like a foreigner. It was cool. “Look at the sidewalks! Oh, they are ridiculous, awesome, super small! Why and wow.“ I was really eager to find some traditional Lebanese, and more specifically, Beirut habits. Like what the old people do: sitting and playing backgammon and reading their papers. It was a rediscovery for me.

You mentioned that you worked hard on your home in order to make it liveable. What do you love about it?

Nader: For me it is at a stage I am happy with. I love my courtyard. What else does someone need or want? As mentioned, I’m a country boy and I need my little piece of nature in the city. If my day is really bad, I can retreat here, strum my guitar, read a book, have a drink or barbeque, or just chill on the couch and feel good.

In a Radio Beirut interview you mention that blues is a selfish process; a process that heals personal pains…

Nader: Basically what comes out of our music in the end is not necessarily pain. The pain might be the trigger. It can be the biggest motivator. What do you feel more than pain? What is your deepest emotion? What is the one that stays with you and will never leave you? It is always the most painful ones that resonate.

Eddy and Nader it has been great to get an insight into your lives in Beirut and to hear about your band The Wanton Bishops. To find out more about their touring schedule see their fan page here.

Photography: Sebastian Dahl

Interview & Text: Göksu Kunak