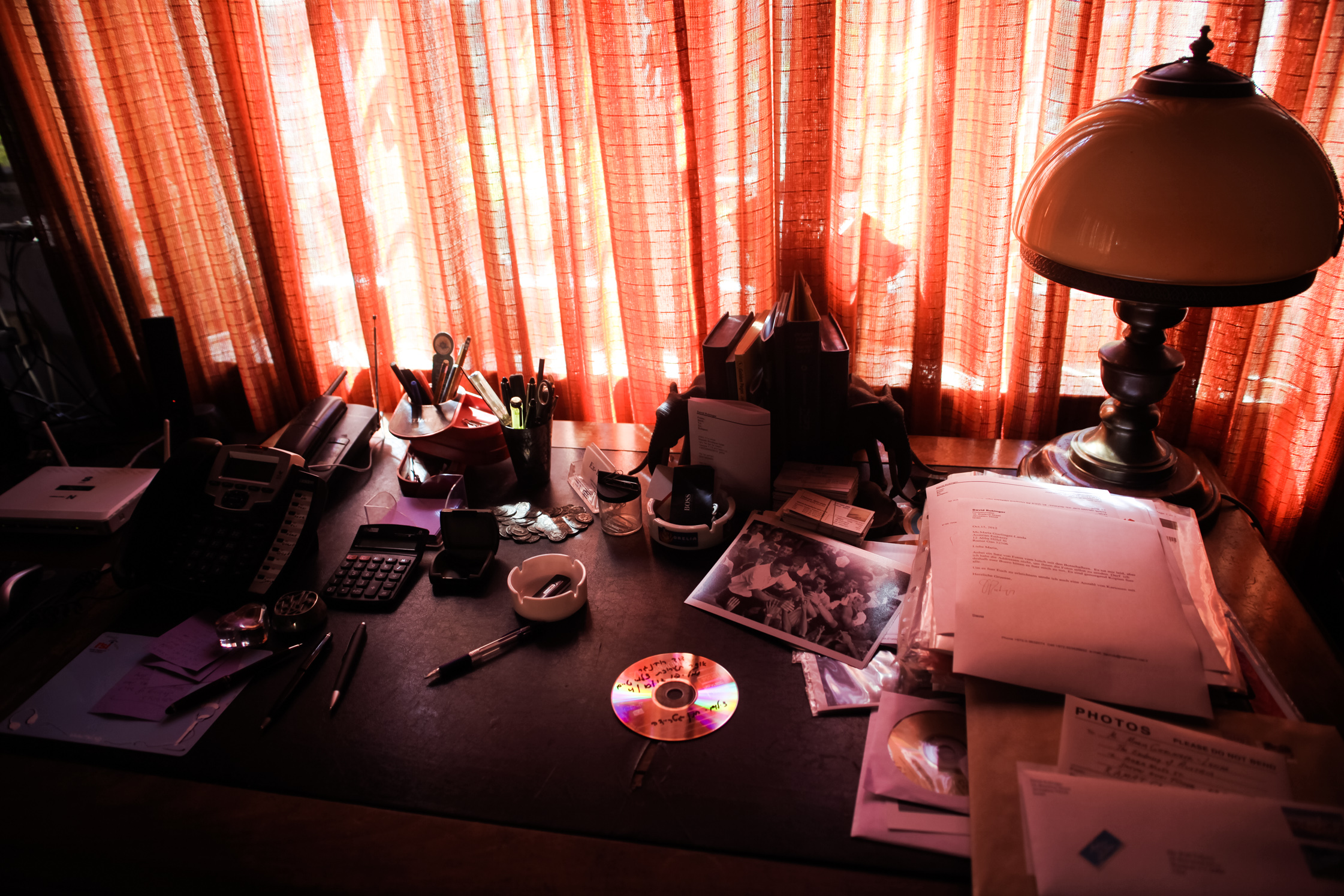

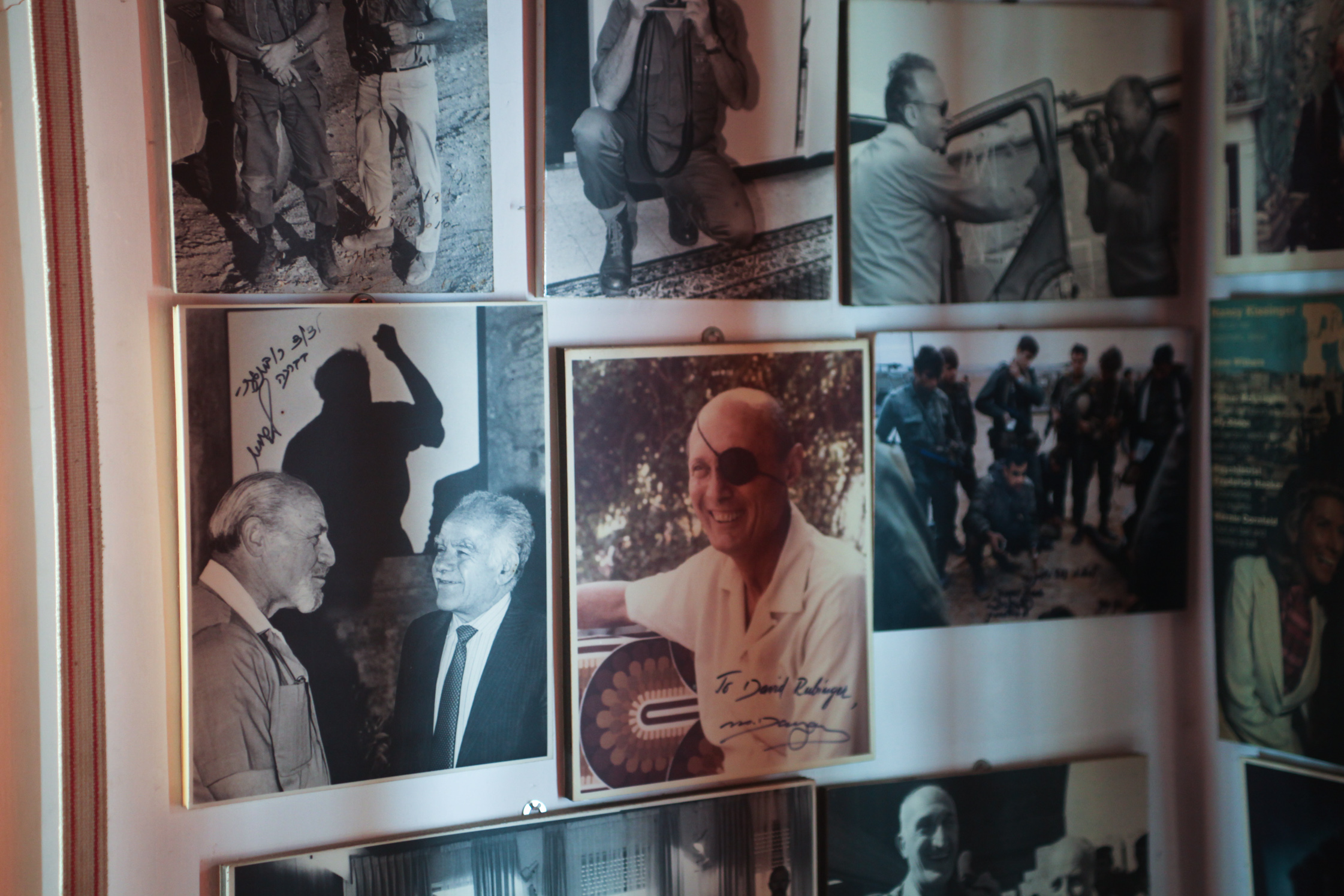

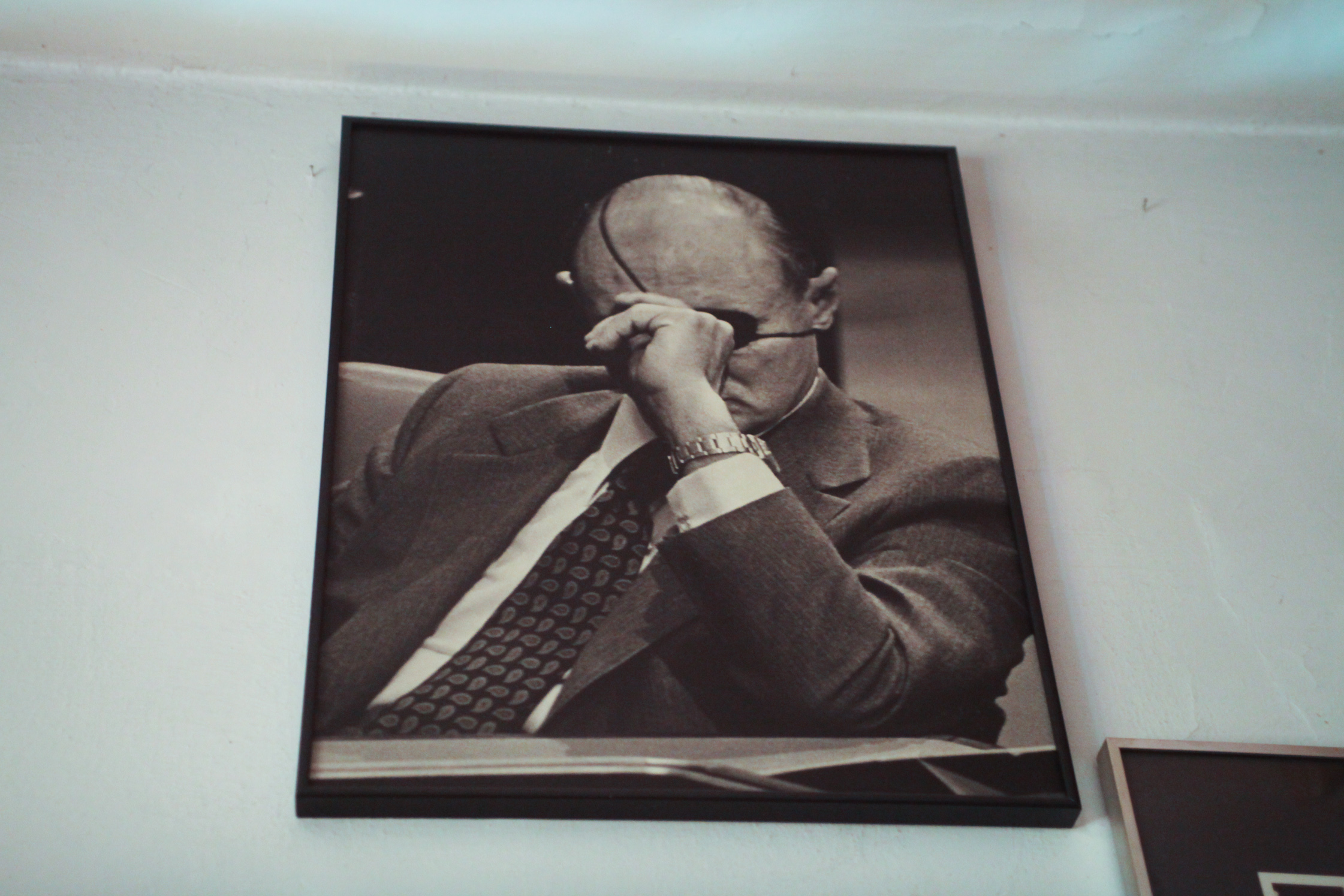

David Rubinger hasn’t changed anything in his house in Jerusalem since his wife died twelve years ago. As a collector of nearly everything, Anni always asked friends and family to bring back items from their travels. Her spirit lives on in the artworks and ethnic masks that cover every inch of the two storey house. Except David’s office. Here, his own photos take pride of place on the walls, and provide only a glimpse of approximately 500,000 pictures that he has taken as a political and war photographer over the past 50 years on Israeli frontlines. The majority of the pictures on the wall are signed black and white prints depicting high ranking politicians. His most popular and important photograph has never been his favorite. In fact he would never have guessed this image would be the one that would make him world renowned. The photo depicts three Israeli paratroopers right after the capture of the Western Wall in Jerusalem in 1967.

In 1924, 43 years before, David’s own life began on the other side of the Mediterranean. He was born in Vienna as an only child to a Jewish couple from Poland. In order to prevent being taken by the Nazis, David’s father, a scrap dealer, was permitted to stay with his sister in Britain in the early stages of Hitler’s Regime. His family however was not. By the age of fifteen, David managed to escape to Israel, however, it wasn’t until 1942 in Paris, fighting in the Jewish brigade against the Nazis, that he fell in love with photography. Well, actually he fell in love with a French girl, that’s how it started…

This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who presents a special curation of our pictures on their site.

88 is an age where most people like to take it slow, stroke the cat, watch TV and go for a walk at most. David Rubinger has just published his first e-book which he proudly presents to me on his brand new iPad. His old electronics, including a computer and a radio from the 80’s have found a new home in a flower bed cuddling up to blue chrysanthemums in his garden. “Who knows, maybe they’ll get children some day,” he says. I follow him into the house in the south-western part of Jerusalem, a city filled with history and culture, religion and conflict. David considers himself far left when it comes to politics. The occupation of Palestine, the wall and the current political direction to the right is not aligned to his personal value system. He is a man informed by his own considered opinions based on experience as opposed the adoption of reasoning and ways of thinking derived from the media or via educational systems. He has been there, in the middle of Israeli history through the holocaust, the founding of the state of Israel, through its developments, its wars and conflicts – up until now. David has never been much of a religious person. But when he came to Israel in 1939, leaving behind his mother never to see her again, his fifteen year old heart was filled with zionistic ideals and naïve ideas. “I was quite extreme, promising myself to never speak any other language but Hebrew and when our ship landed at the shores of Haifa, I saw the Arabic market from afar. I instantly thought: Well that’s probably where the Arabs buy their women. This foolishness I blame on reading too many Karl May novels,” he says laughing. As many of the European Jews coming to Israel during that time, he lived in a Kibbuz, a typical Israeli collective community. David fondly remembers the three years he spent there as being the most peaceful of his childhood, picking bananas, helping in the barns and above all, not being an outsider anymore.

Back in Vienna, David had only one true friend, Poldi. Poldi was the son of a pub owner and Austrian to the core. David used to hang out after school, making carvings from little pieces of wood with a file. In the 80’s, decades after seeing Poldi for the last time, David got a phone call from a stranger in Israel. The caller had been in Vienna sitting in a taxi chatting with the driver who happened to be Poldi. Poldi had asked this person to track down his old friend David once they were back in Israel. As a result, David found himself sitting in an Austrian cafe waiting to be reunited with his first and only friend from his childhood. Poldi was exactly as David had imagined him to be as an adult – through and through Austrian, dressed in a traditional Lederhosen and hat. When he told David about the horrible time he had fighting in the war at the Russian border, David realised that the battle line could not have been far from where his mother was most likely killed in a concentration camp. Suddenly his old friend became a soldier, killing for the German cause which included wiping out the Jews. David didn’t know how to look at him anymore let alone speak. He was ready to get up, make an excuse and leave, when Poldi took out a little object wrapped in a linen handkerchief. “I want to give you this as a gift from me,” Poldi said, pushing the small package across the table towards David. When he unfolded the linen he discovered his carving file, the one they used to make carvings with together, back when they were boys and before the war ended their childhood prematurely and separated them. “I realized, that Poldi has held on to this file for more than 60 years, to give it to me and that nothing else, that happend in that time was important to me”

When David turned 18 he was a happy but still stateless Kibutznik. Israel would not be founded for another six years. Even though the English had restricted the admission of Jewish refugees, his will to fight the Nazis motivated him join the English army. “I didn’t really get to fight much, though. They tried to keep us out of the line of fire” and with a boyish smile he adds, “it was more like a world cruise paid for by the king.” Besides Africa and Italy, Belgium was one of David’s destinations. Stationed at Liège he had two days off along with tickets to the ballet to explore Paris and distract himself from the war he wasn’t fighting in. Arriving five minutes too late David and his comrade missed the show and went for a drink around the corner at Rue Scribe. He will never forget the name of the street, he muses reminiscing about the past. But either the street name has changed or his memory has not served him so well as Google maps cannot locate the place where David and his friend met two girls as French as can be: Jeanette and Claudette. “We didn’t see any ballet that night” – he says with boyish grin.

After a romantic dinner near the Eiffel tower a “friendship”, as he describes it, developed between him and Claudette. He even ran away from his station to meet with her twice – once being caught and incarcerated for seven days. Quite some trouble to go to for a friend. After a few months, David left Paris and Claudette came to farewell him at the train station. I imagine her with curled up, side parted hair, deep red lipstick standing in the fresh September breeze – a sight to remember. Claudette made sure she would never be forgotten. On that day at the Parisian train station in the early 1940’s, Claudette gave David his very first camera, a 35mm Argus.

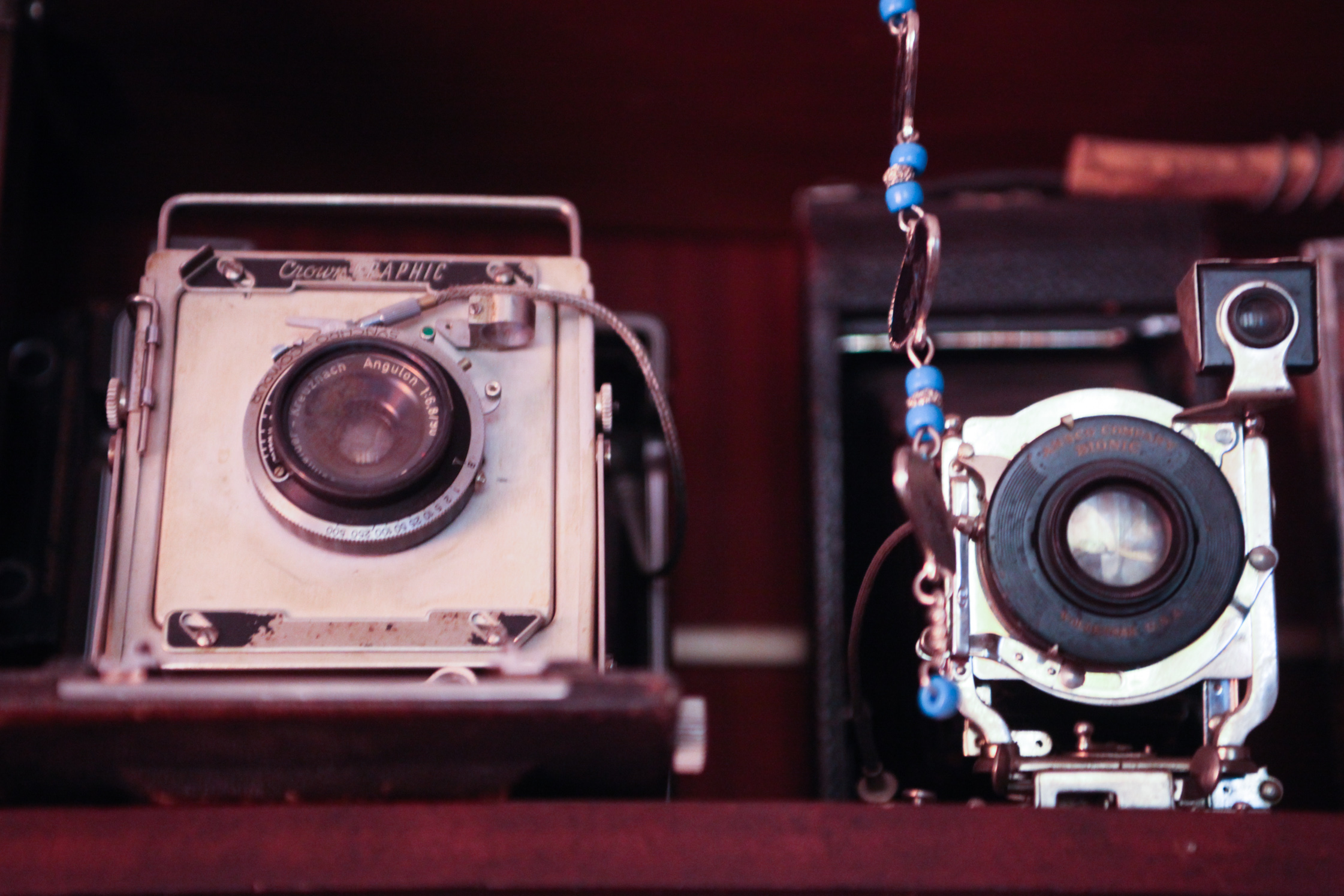

Claudette inadvertently aroused a hidden passion within David. He became sure that after the war he wanted to become a photographer. Back in Israel when the British army declared his quarter a military zone and people started throwing food over the fences to feed those living behind barbwire, he was there with his camera. First he sold prints to neighbours and then to local newspapers and magazines. In the war of 1965 he was offered his first real assignment by Time LIFE. Arriving at the hotel where all the correspondents stayed at, he approached Burt Glinn, an already well known Magnum photographer and asked him whether he wanted to share a room. “I thought, if I rented a room in a fancy hotel, Time LIFE would kick me out before I’d even begun. Burt thought I was gay.” David soon found out, that Time LIFE treated their photographers more than well. “A colleague from Poland, who later fell in Gaza once said to me: if my expenses aren’t at least 300 dollars a day they would think I’m not really working.” By that time photographers of Time LIFE magazine weren’t even allowed to fly economy. “Prestige was everything to them – it’s not hard to get used to that. It’s a pity how this has changed, photographers aren’t valued and supported anymore.” His first photo published internationally for Time LIFE depicts a nun holding a set of dentures she had retrieved after a patient had dropped them from a Catholic hospital window onto Jordan territory.

David worked for Time LIFE for 38 years, being present at the frontline of every Israeli war. He met and portrayed dozens of international politicians and was one of the few photographers permitted to take photos in the Knesset. His editor at Time LIFE once spaeking about David said, “that he doesn’t merely search for good pictures but for people who can connect with their object and build relations – no matter the costs”.

David states, “I’ve never been a paparazzi. There are certain things the public has no right to see. I would have never published a picture of a prime minister zipping his pants. Even the highest ranking politicians have to pee sometimes. That doesn’t make it anybody’s business.” The image that brought David global acclaim portrays three paratroopers at the Western Wall directly after its recapture in the Six-Day-War. The Israeli government published the image hundreds of times, giving it out to everyone. Apparently even other foreign photographers claimed and sold it as their own. “Today I’m grateful to the thieves – they made it famous,” David says. He actually didn’t see the potential of this photograph at first. It was his wife who singled out the image after scanning through his photographs taken on this particular day, and encouraged him to send it to the agency. “As always, the woman was right.”

After the war, before returning to Israel for good and becoming a photographer, David travelled back to Germany to find his unfamiliar cousin Anni, who survived the holocaust. There he got his first Leica for 200 cigarettes and a kilo of coffee. David and Anni decided to fake a marriage to get her to Israel. “We didn’t even have a proper wedding, it was fake after all.” The couple had two children, five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. “We just forgot to get divorced for 45 years,” David says, pointing at a picture of his wife hanging on the wall between the objects she had collected.

Thank you, David for sharing your truly fascinating life story with us!

To get an impression of David’s prize winning photography, we recommend to have a look at his book “60 years of Israel” here.

This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who presents a special curation of our pictures on their site. Have a look hier.

Text & Photography: Louisa Löwenstein