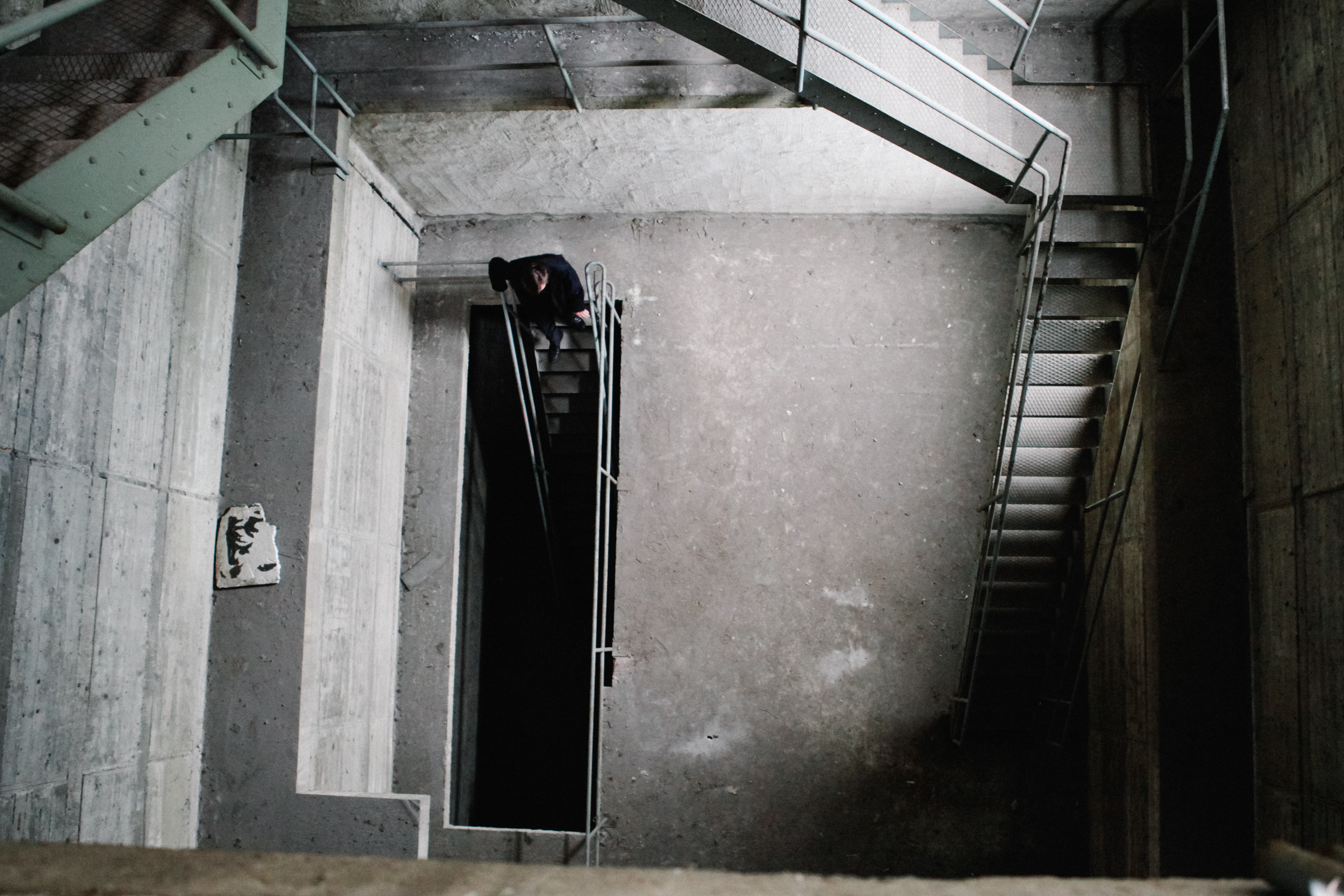

In Berlin, the name Brandlhuber stands above all for house number nine – the house in Brunnenstrasse in the Mitte district where you can plug your headphones into the façade. Where the narrow, concrete stairs in the courtyard wind their way up four floors and where the unfinished and the mutable form the heart of a modern and sustainable architecture. Arno Brandlhuber’s work stretches far beyond the borders of Berlin Mitte’s creative habitat. As an architect, he is concerned with the reality of our urban present and is committed to preserving what the city was once known for – its heterogeneity, the oft-cited ‘Berlin mix’.

“The city is the best context in which to draw together diverse groups and perhaps the best cultural achievement that we can boast of. There is no Tabula Rasa and no White Cube. It is always to be found in different conditions and that is of great interest to me.” This concept is embodied in his own four walls ‘We were playing with those conditions, and were trying to bring in as many rules from the outside as possible.’ It is thus from the neighboring buildings that the ground plan of the loft emerges, highlighting the fact that good architecture can always be two things: good-looking and sustainably designed.

This story is featured in our second book, Freunde von Freunden: Friends, order within Germany here, or find the book internationally at selected retailers.

This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who presents a special curation of our pictures on their site.

How did the construction in Brunnenstraße originate?

The Gallery WBD – Wand, Boden, Decke – was located in the courtyard. The structure was quite raw back then: the building basically only contained a basement, the starter bars were fully exposed, and there was a gigantic hole. Eventually I asked Michael Dethleffsen, co-operator of WBD and owner of the property, if he wanted to sell me the frontal part of his dominion. Back then the land price was pretty cheap and we found a bank to finance it. In the beginning we had the idea to have the two floors put in concrete. The Gallery KOW, which was located downstairs, eventually needed more and more space, then 032c joined as well. All this lead to a full house.

So it grew organically?

Since the very beginning the gallery KOW was part of it, but everything else just began to develop naturally. As the gallery would work a lot with video, it was obvious that they would get the light-protected room that is partially two levels and thus corresponds to the original house structure. The original investors went bankrupt in the 90s when two-thirds of the base plate’s were concreted. This is when we decided to just built on top of it.

This was in 2007, a time during which the biggest parts of Mitte had already been gentrified. How did you incorporate Brunnenstraße’s direct environment within the construction?

Back then, there was nothing north of Torstraße. There was St.Oberholz at Rosenthaler Platz and the bakery across from the street. Brunnenstraße was quite dingy then. Through the basement we knew the layout and were aware of the elevator’s plausible location. Besides that, we had a contract with the owner of the rear house that allowed us to cut the building from above so enough sun would still fall on it. The only questions were really where the stairs should go and how high the storeys should be. We somewhat constructed a puzzle game, creating a completely different planning process. It was a game with the conditions of bringing in as many rules as possible from the outside.

Do you prefer working with existing objects in order to deconstruct and decontextualize them, or do you prefer to work from scratch?

I much rather working with existing structures, just because I think that the city is the best model for gathering different groups. Perhaps the city is the best cultural achievement that we are currently dealing with. There is no tabula rasa nor a white cube, as it is always stored under different conditions.

Could you quickly explain the theme of your first solo exhibition “Archipel” and what role the 1977 manifesto “Die Stadt in der Stadt. Berlin – der Grüne Archipel plays within it?”

In the past years we intensively concentrated on Berlin’s property policy. Here the central question was concerned with whether it was right to privatize properties or keep them in the hands of the city, as it would enable its urban planning. For example, all forms of temporary use are only productive in the longer term if they are secured through public ownership. The theoretical manifesto, which lays behind Berlin’s city development policies for the past twenty years, is called ‘critical reconstruction.’ Its meaning is the regress in regards to earlier construction tradition. This is why we have so much stone wallpaper and like to recreate castles nowadays. We were searching for description systems that can be re-actualized in another manner.

The manifesto Die Stadt in der Stadt. Berlin – Das Grüne Archipel which Ungers developed with Ovaska, Riemann, Kollhoff, and Kohlhaas, referred to a very different scenario. Back then, Berlin was shrinking and it was all about revealing steady areas and determining their identities. Formerly, one thought it necessary to depict these differentiated lifestyles within architecture. These homogeneous islands have been located in Berlin especially within the last five to six years.

Berlin Mitte is being increasingly homogenized, there are high-priced milieus while on the other side low-income households grow larger at the city’s periphery. The talk about the great mixture in Berlin was always an enjoyable topic, but now segregation takes place in homogeneous milieus which is the wrong development. The city is principally able to absorb different protagonists and tie them together. The exhibition attempts to encourage this very discourse, one to which artistic context fits better than the isolated architectural context.

Couldn’t one take the model further with grasping and expanding the green temporary spaces as heterogeneous meeting places?

Exactly, the green Archipel also says that the green spaces are meeting places, but that we decreasingly possess intermediate spaces. This is happening all over. The question is what we want to support, a heterogeneous city that naturally produces frictions, or do we want to retreat to our individual ghettos?

Is there an example where sustainable city planning functions well?

Amsterdam is a good example. The city specifically buys inner-city properties in order to reassign the heritable building right so that the buildings fall back into the public sector every 30 to 60 years. This stimulates different usages of the building.

What is exceptional about the building material cement?

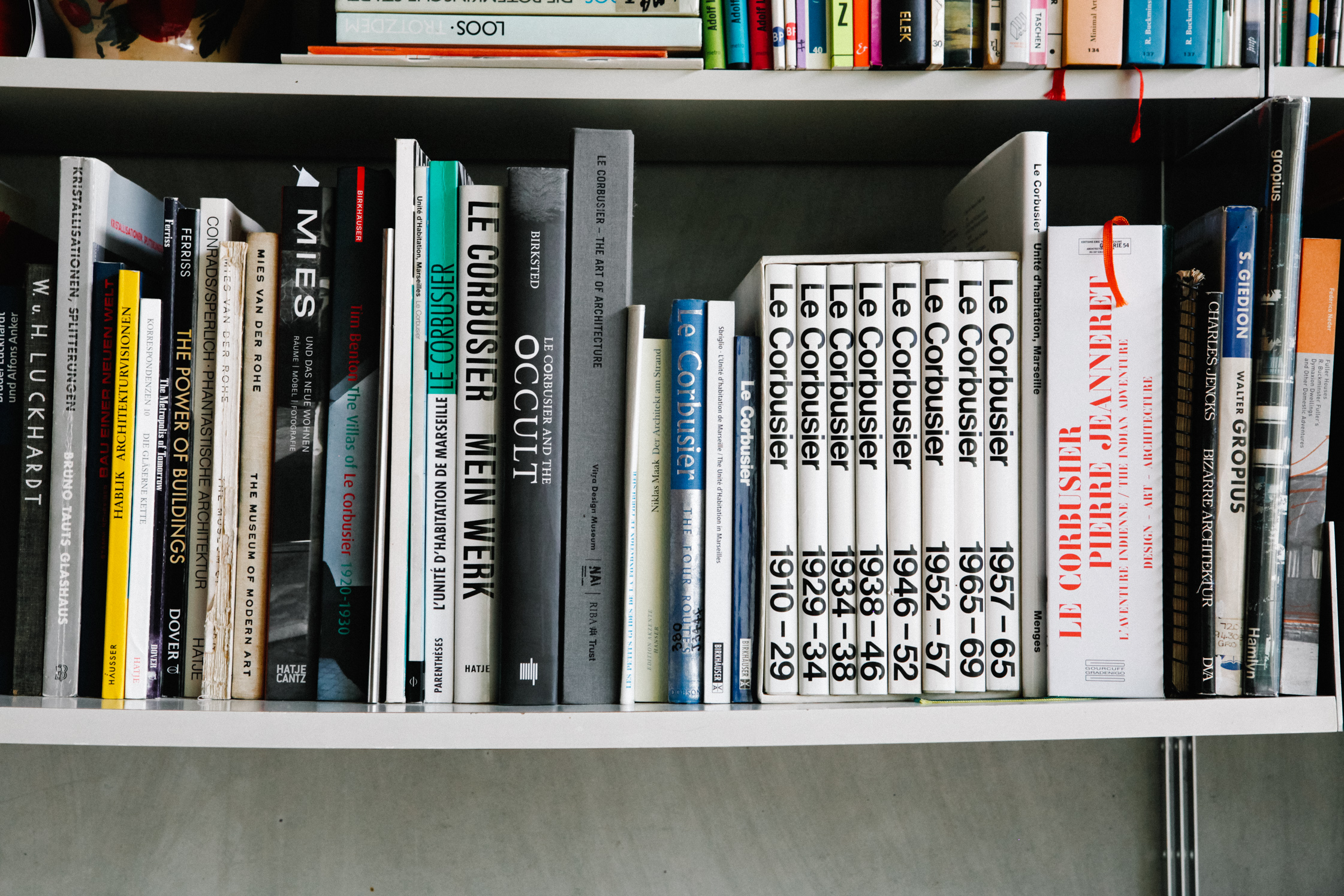

I find it very interesting that cement can take on every form, that it is undirected and amorphous, and contains a vast history in regards to its personal production and processing. Cement is very usable. For example the floor is bare cement that is smoothed during curing. One is always happy about textures and traces in a floor as they narrate a story. I like the brittleness and bulkiness of it. Besides this, it just looks really good. For example the Brazilian constructions of Lina Bo Bardi are remarkable or the older buildings of Vilanova Artigas. Cement experienced a discredit in connection with Unwirklichkeit der Städte in the seventies and eighties. Now it becomes obvious that the material and social processes cannot be equated.

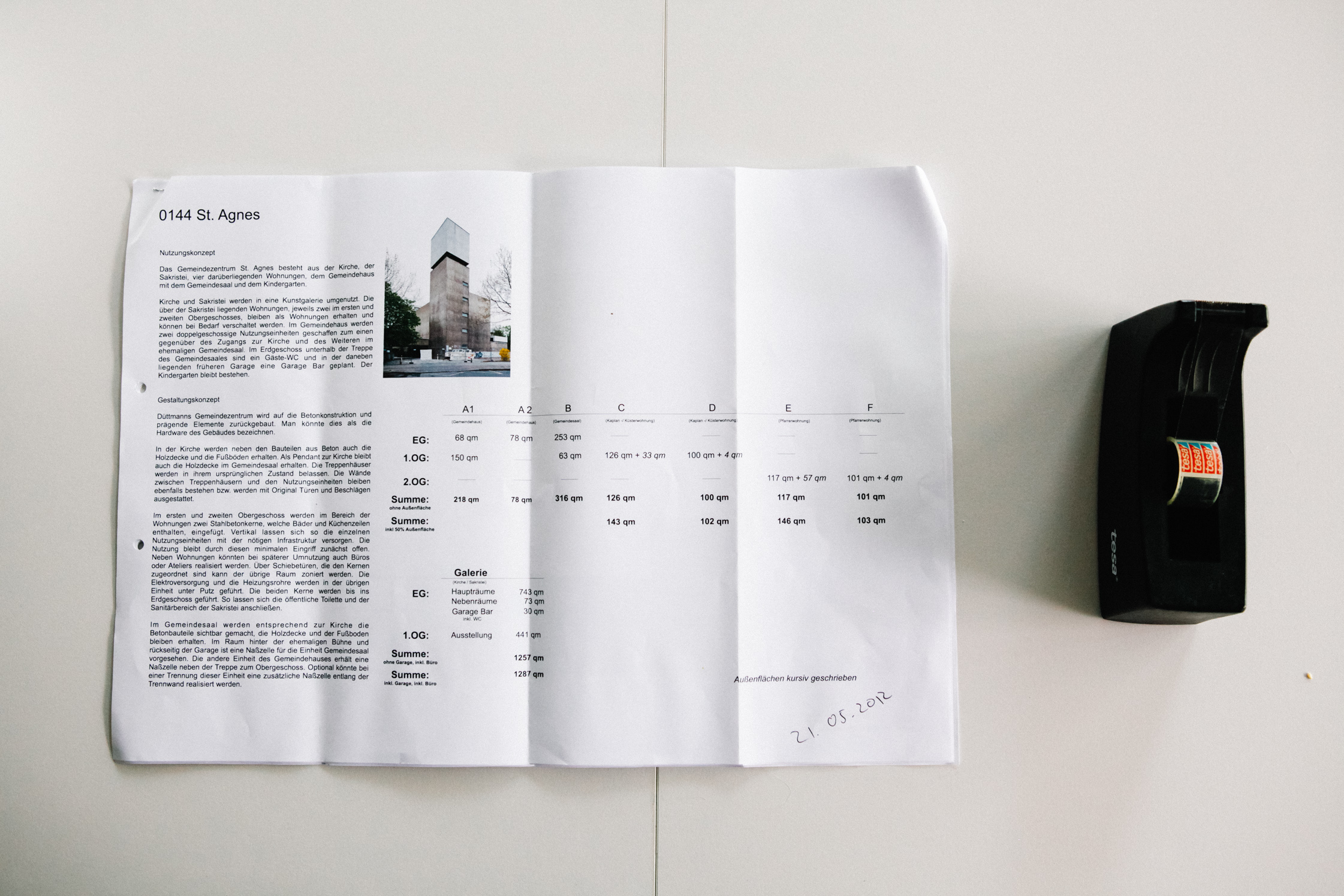

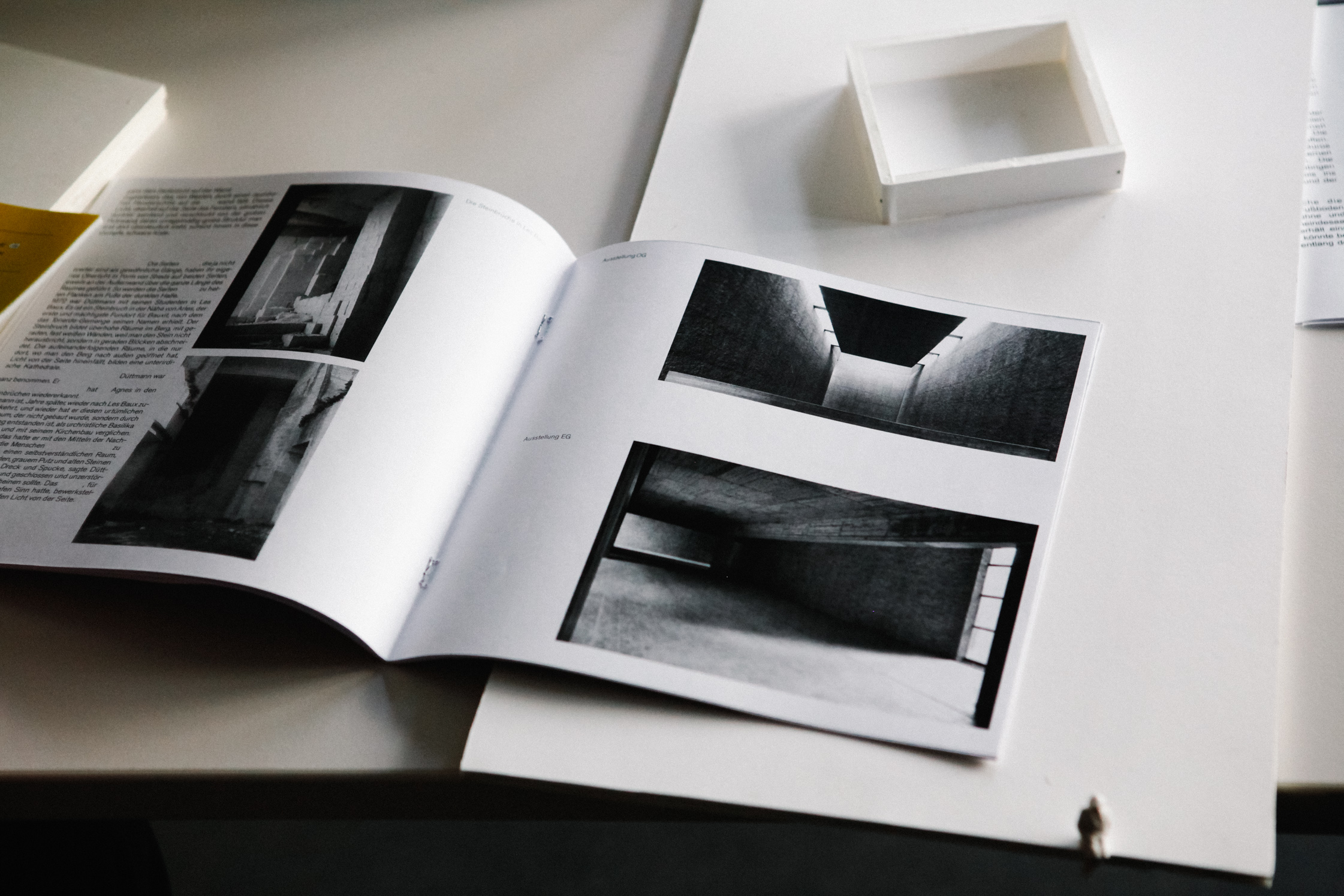

That is the great thing about St.Agnes. The church stems from a time during which building materials were perceived very differently and whose expression was valued as a possible future. This goes very much with the spirit of Alison and Peter Smithson and their idea of brutalism. The definition of brutalism constitutes here of something very different than the actual word itself. It embodies the idea of sociality, the conviction that a building is defined by its user. This was completely forgotten about in the 70s and 80s, which makes St.Agnes very interesting nowadays as it serves as a classic example for brutalist architecture in Germany.

When was the church built?

St.Agnes was planned and realized by Werner Düttmann, Berlin’s senate construction director, in the mid sixties.

How did the project of converting the church into an exhibition space originate between you and Johann?

The parish kept losing more and more members, which is how the three parishes got together and fairly quick decided that St.Agnes was not to be the common center, but one of the other two old churches. The demolition of the church was initially planned, but then Berlin’s monument conservation got committed which led to the church being on the market.

I communicated this to the art field, and there were two interested parties in regards to the object. But Johann firmly put across his gallery concept and essentially acquired the church. One could say that Düttmann had had created the perfect exhibition space.

As you said the room was pretty ideal for this project, what is the biggest challenge for you as an architect in this conversion?

The aisle is very problematic. The walls don’t reach to the ground, thus there is no true surface for hanging. A storage area is lacking as well. I am very fascinated by Düttmann, who also constructed the Academy of the Arts in Berlin.

We don’t want to dismember this strong gesture with lots of small, individual measures that is arranged within the material. We want to apply an individual gesture that, besides the spatial requirements of an exhibition room, also meets the necessary technical conditions.

Where does your strong fascination with urban sociology stem from?

I think it is due to a past professor, Thomas Sieverts, who significantly shaped me. He brought extremely interesting and young assistants to the university, who knew plenty about French post-structuralism and he himself would ask very different questions. It was less concerned with city planning in sense of actual panning, something I couldn’t believe in. I am interested in the question of how changes can be solved and promoted.

Thank you Arno for this fascinating conversation. It’s great to see how your inspirations and thoughts are translated into urban realities. For a complete overview of Arno’s work have a look at his website here.

This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who presents a special curation of our pictures on their site. Have a look here.

Interview & Text: Antonia Märzhäuser

Photography: Philipp Langenheim

Translation: Lara Konrad