Upon entering Antonio Colombo’s apartment there’s no other option than to be overwhelmed by a sense of incredibly good taste. Only a few inches of wall space has been left visible, the rest is occupied by a fraction of his impressive art collection. The selection that hangs on his walls comprises an eclectic representation of modern and contemporary art history: works by Alghiero Boetti and Antonio Donghi are mixed with a range of American street artists.

Within his home Antonio has a range of designer furniture, with the work of Schifano and Nathalie Du Pasquier rugs, along with shelves packed to the brim and a variety of indoor plants. On a coffee table an over-sized shiny pink roll of thread commands attention encased in perspex. It’s a work entitled “Il Giro D’Italia” by Alberto Garutti and is the first hint to Antonio’s intertwining passions.

As an avid collector, gallerist, businessman, and entrepreneur Antonio is many things. He is the owner of Cinelli, a bicycle brand that needs no introductions, president of A.L. Colombo – the family tubing and piping manufacturing business that has been running since the beginning of the 20th century – and last but not least, owner of Antonio Colombo Gallery in the vibrant district of Brera in Milan. During our discussion we find out why Antonio is not into trends, a lot about the Italian “art system” and how he blends all of his activities together so harmoniously. Cycling culture and heavy industry have never seemed so related to each other.

The first thing that comes to mind when talking to you is the fact that you operate within many different fields. Who actually is Antonio Colombo?

My entrepreneurial path is atypical. After starting out in the manufacturing world in the heavy steel industry, for decades now I’ve arrived into the area of creative entrepreneurial work. My education and my passions have always been deeply linked with art. I’ve had an ideological education. I’ve lived through 1968, the revolutions; somehow I consider myself a democrat in the American way. I’ve never loved the idea of a power driven business approach. My path has always been antagonistic and in opposition to situations where the entrepreneur is the one holding the economic power. Art has always accompanied my life. I’ve always wanted to work “in” art and design, not “with” art and design.

What do you mean exactly by “antagonistic path” and how is this concept applied to your artistic activity?

The gallery is no different to all the other businesses I’m involved in. It all starts the same way: you put on a suit when you’re twenty something, you go to the bank to figure out how to finance your ideas and it all goes from there. Then comes the switch. You suddenly realize you have to bring something new to the industry. My first steps in the art world required taking a necessary alignment with the galleries that I considered to be good galleries. The gallery system imposed a post conceptual aniconic art. I never fully embraced or aligned with that, but I understood that it was necessary to gain a certain standing in art related circles. My partial “schizophrenia”, my contrary thinking and most of all my desire for alternatives brought me away from the traditional “cultural salons” if you know what I mean.

When was this happening?

Twelve years ago, when I opened the gallery. I was already immersed in the art system, but in my own way, as a buyer. I selected what to do and what not to do, what to see and what not to see and which fairs to attend and not to attend. I was already a collector. At that stage I didn’t know where to put my collection anymore. It came quite naturally. I needed the gallery to be an extension of my collection. So I started selling with the same criteria as if I was buying. This has always been the key for me. While I was moving away from the traditional way of conceiving an art gallery I started following alternative paths, like the street scene. I was attracted to anything with an overbearing and mighty figuration. I started following art that was highly charged with imagery. At that time this style was mostly happening in California.

When did you make a breakthrough?

It was probably with my first show at Triennale Milano called “Beautiful Losers” in 2006. It was huge, even if surprisingly the show didn’t get quite the amount of press it should have. We showed Kaws, Ryan McGinley and Futura – just to name a few. Raymond Pettibon’s room was great. There was an unusual mix of great artists mixed with other elements of youth culture. At this time in Italy art was all about post conceptualism. The good art is conceptual, there’s no difference between conceptual and non-conceptual art. Bringing this message out is my challenge. I’m not saying I don’t love conceptual art, I do, and I own a lot of pieces.

But?

But I think it’s done with! Or, rather, there’s so much more to it. Outside of Italy there are breathtaking examples of artists quickly stepping up to the next level even though their soul was the street. Kaws is a great example. Basically today there are some tiny perceptions about the fact that there’s room for a renewed art where the image – and by image I mean elements that can be given a name, like a vase is a vase or a tree is a tree – can be treated with great innovation. The Clayton Brothers, who I recently showed at the gallery are also a great example of this, especially for their maturity and strong images.

What do you think should be done to change the art system?

Now that’s a hell of a question! There needs to be more generosity with exhibition programs. It’s unbelievable to me that there was a four month Marina Abramovic exhibition in Milan in 2013.

Let me provoke you. That’s trendy!!

Ah yes, it’s trendy, but it’s also baroque. I am not interested in “trendy” . Don’t get me wrong, I think she’s great, she did a lot of interesting things, but moving on is necessary and showing the public more is a must. I don’t think it’s only a question of generation, it’s not only about innovation. It’s a cultural issue we’re facing in Italy.

You recently came back from Miami, how did you feel about it?

Miami is a circus, a cinema. My first experience was ok. The fair I was in was a smaller one, very selective. Miami is interesting, there’s a certain excess which is ok for Miami I guess. In Italy we are stingy, in Miami they are excessive.

You earlier mentioned California. Did you ever live there?

No, but because of Cinelli I had to go there more and more often. At the time the urban biking community and fixed gear phenomena was booming. All these things didn’t exist in Europe.

Can the whole bike-related culture be considered a trend? When the movement of fixed gears hit Europe it kind of felt a little de-contextualized and twisted. In fact the trend seems to be fading. If we talked about it two years ago it would have been such a “now” topic but today it feels like the whole thing had an expiration date.

I don’t know. I don’t care. I never asked myself that. I’m not a trend hunter or a cool hunter. I think this way of living the bike is a true lifestyle, not a trend. It’s based on founding values. I guess one can see it as a trend, but I don’t. There might be people doing it just because it’s cool, but then again, I’m not interested in that. I find it an authentic movement based on positive values.

On this note, I also don’t think street art is a trend. It was born 30 years ago and we’re still discovering it and figuring it out. The great discovery with street art is that it is an art that wasn’t born in the academy. It is an art form that reworks itself bit by bit, with great attention to the needs of a younger generation, to social needs in general and accompanies humanity. I definitely wouldn’t call all this a trend.

And we jumped from art to bike in California. How do the two things blend?

Well they do. While discovering what was going on in the bike world I found out that the link with art was very strong. For example Barry McGee who I met at the time told me he had always had a special passion for bikes since he was little. His dad was a Hot Road master. He turned a Cinelli BMX into a mini Hot Road.

Another Cinelli icon is the Keith Haring bike that I own now. Its story is very interesting. I’ve always exchanged bikes with art pieces. So I gave Keith two bikes, one for him to keep and he returned the other one with his painting on it. He used to lend the one he kept to Futura. He was a messenger at the time. Then six months ago he also gave me a customized Cinelli. It was the one I gave Keith Haring in the 80s. I didn’t expect it and I’m still surprised by it. Also, last week, I was in New York for the RED auction at Sotheby’s. I was at a dinner with Futura and Alfred Bobe – he’s like a legend in the bike world – and we talked about the Keith Haring story together. All this is not part of a marketing strategy, it all comes naturally as a consequence of a special empathy. It’s not like Hennessy collaborates with Futura, or Dom Perignon with Jeff Koons. This is my life, these are parts of it. Sport and art go together.

Looking at you, the way you dress, and present yourself it all seems so far from you. I mean you’re very elegant, it’s hard for me to envision you hanging out with street artists.

Yes, I don’t have any tattoos, I don’t have a motorbike, I don’t play any instruments and I don’t do any drugs (laughs)!

Is there a motivation? You promote an alternative lifestyle, an alternative vision. Why didn’t you choose to change or adapt your own personal style?

No, there is no particular reason. I think that art and literature can be sort of like keys that open the door to living different worlds. You only have one life and you can’t be everything you are attracted to and everything that intrigues you. My life is nourished by my different areas of business and interest: art, cycling and culture.

Is there a particular piece you’re connected to in your house?

I can’t really say there is. I own so many things I love. This Borra from the 50s definitely deserves attention. I also have some Zanichelli’s. I’m really attached to this artist, particularly for his life. He died of Leukemia when he was really young. I simply love his imagery.

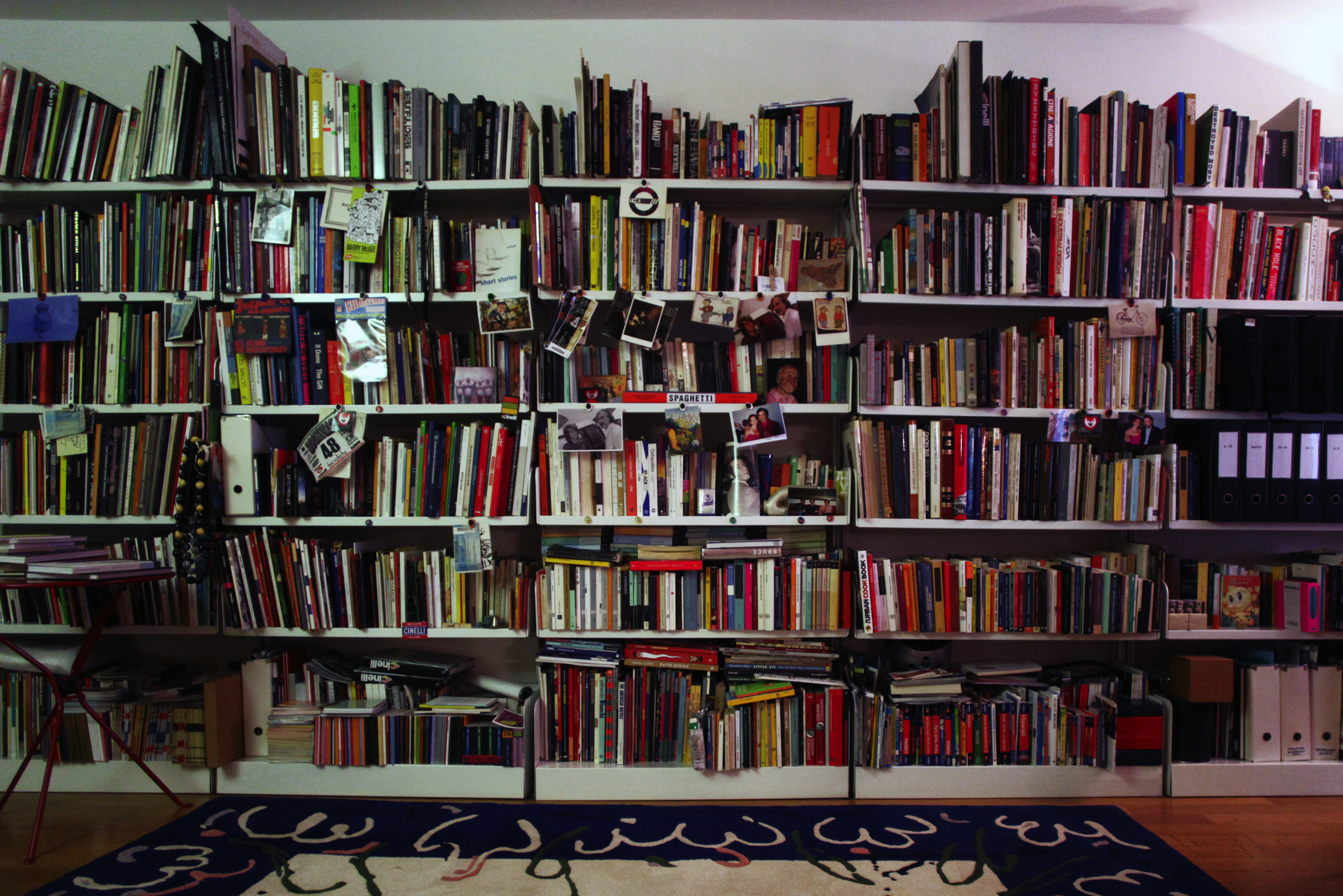

Looking at your bookshelf one cannot help but notice the amount of books and object you have stored here. Is there an even percentage divided between art, bikes and heavy industry?

No (laughs)! There is no reference to the steel industry in there, there is a lot of design though. The rest goes without saying: art catalogues, books, many Cinelli books. There’s an aspect that deserves attention and kind of blends in my other activity. A.L. Colombo manufactured steel piping for many different heavy industries such as aircrafts. My dad used to build pieces of tubular furniture using bicycle handlebars inspired by piping back in the 30s. The drawings were by Breuer and Mussolini’s house was full of them. My research on this was interrupted for a while, after I made this book. I would love to get back to it. You can imagine how after the wars we weren’t so proud of it. Everything involving fascism is a historical memory that Italy tried to delete as much as possible.

But as a design era a lot of great things emerged, I mean, this book is great, no matter what these products are related to.

It was great, and the tubular trend definitely continued throughout the 50s and 60s. I should put more passion into it, I still have pieces, I even talked to Triennale about it. We will see.

Let’s keep browsing your bookshelf. You could spend weeks going through all these books!

Here you definitely must see this, Fritz Kahn. He did an outstanding work on mechanism. He was an engineer in the 30s. His work was all about the comparison between man and machine and mechanical machines. He created amazing illustrations. He was such a visionary.

It reminds me of the Clayton Brothers artists you recently exhibited. Yet another great example of how your activities and your artistic paths walk alongside each other and intertwine in an unbelievably intelligent way.

I guess you’re right. They do have something in common. The paradox and the surreal imagery.

Thanks for showing us around your gallery and your beautiful house, it’s been such a pleasure. To find out more about Antonio’s gallery visit his website here.

Photography: Marco Annunziata

Interview & Text: Massimo Cannavacciuolo