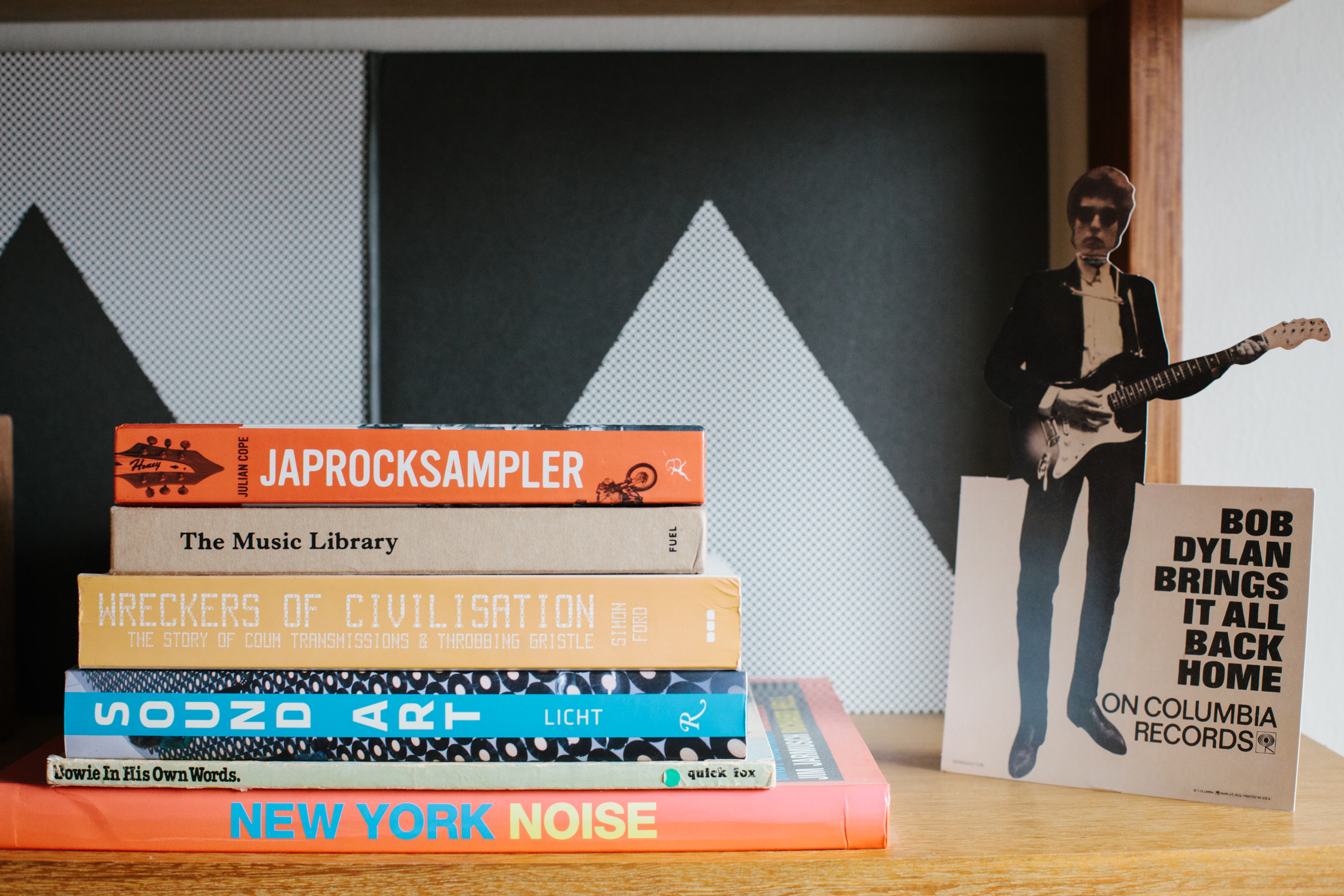

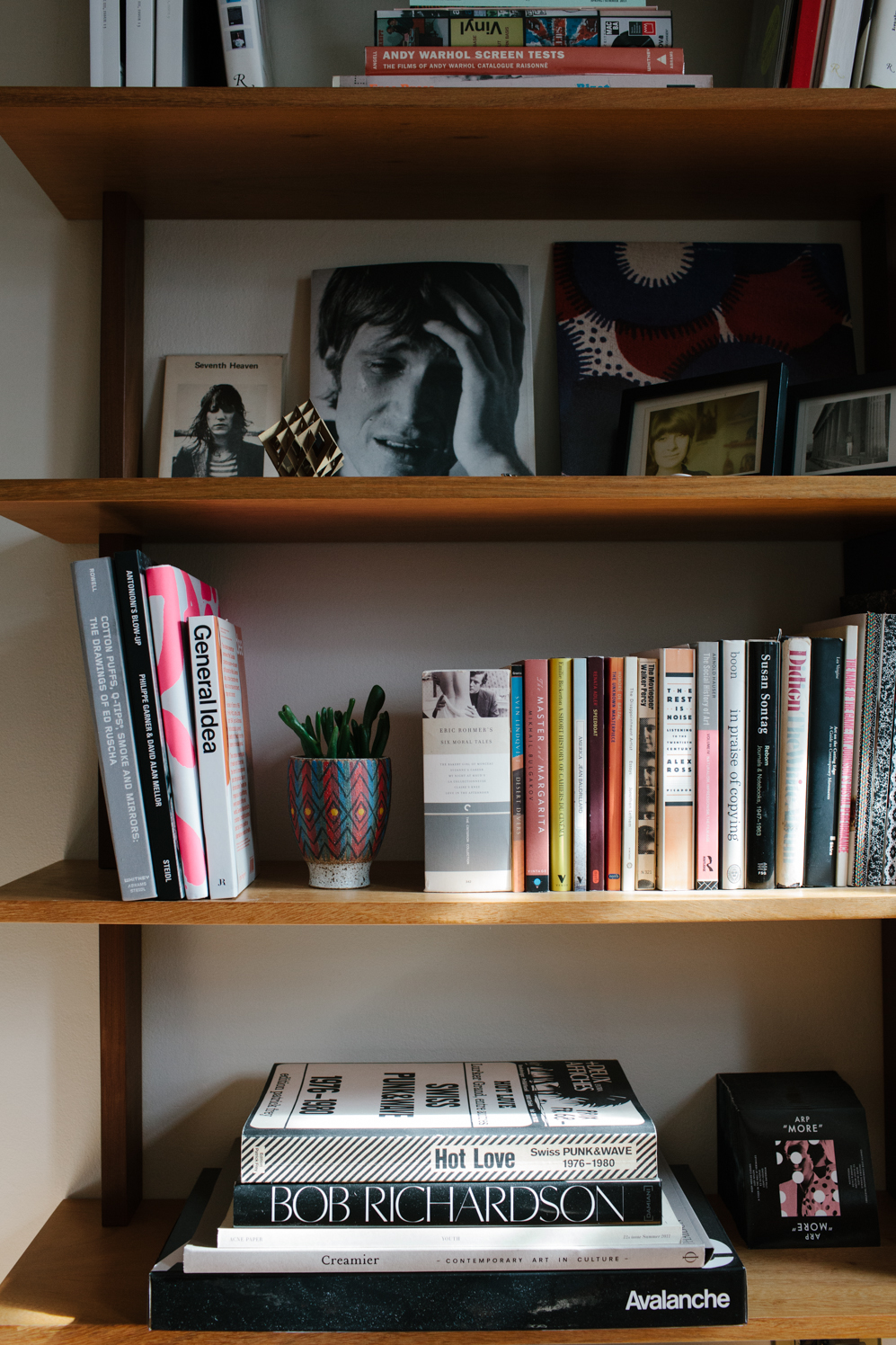

Alexis Georgopoulos’ home, like one of his songs, is a comfortable mix of many influences. There are woven chairs, a rounded kitchen doorway, and stacks and stacks of art and culture magazines. Lovingly ragged, they have been paged through frequently and date back at least half a decade. There are heavy art books, a pair of low shelves boasting a modest number of thoughtfully curated records, and a few scattered fiction novels, as he admits, “I’m more of a non-fiction person.” Everything has a sense of purposeful arrangement: “this is here for that reason, this is there for that reason.” It’s gorgeous and deliberate. Again, like one of his songs.

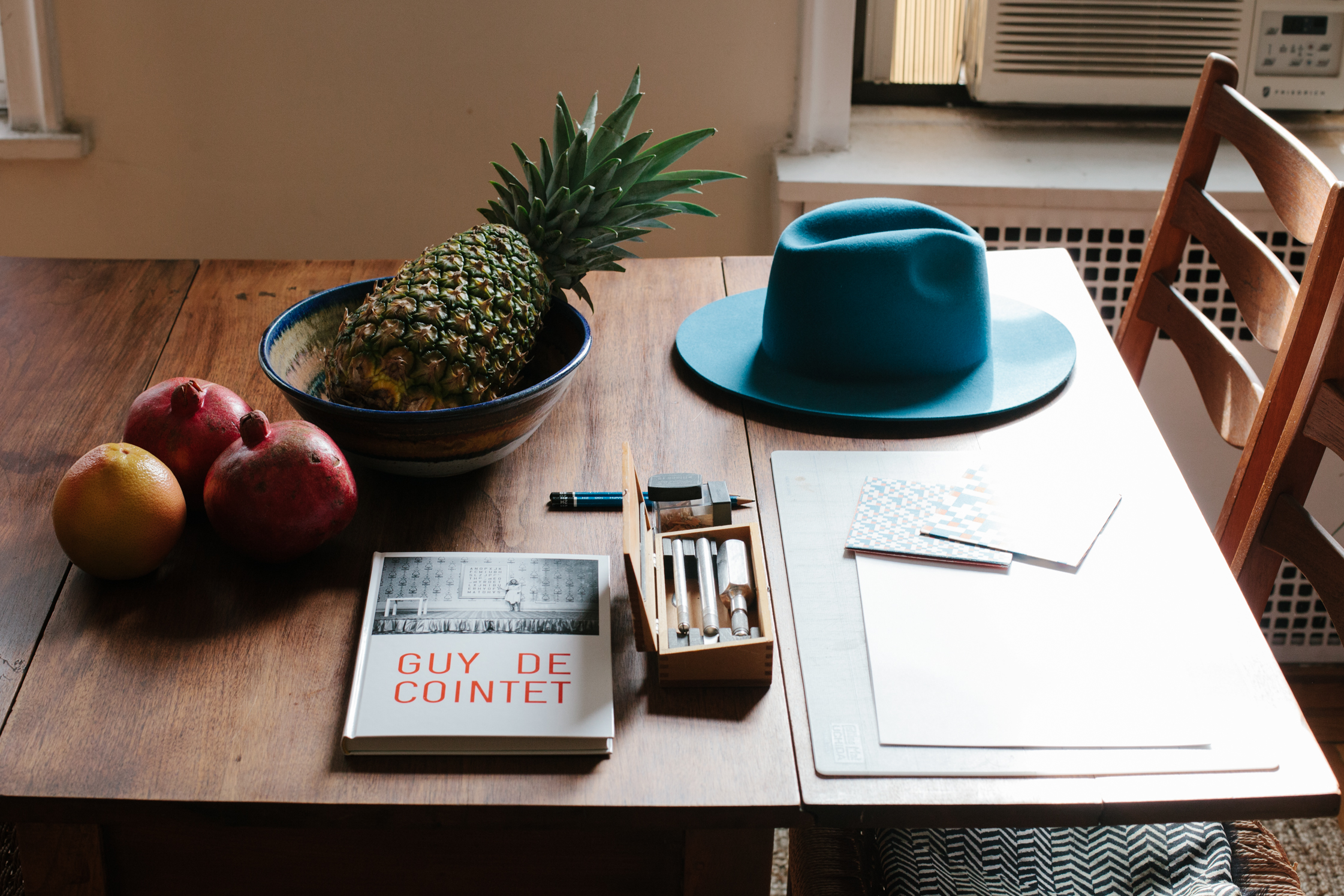

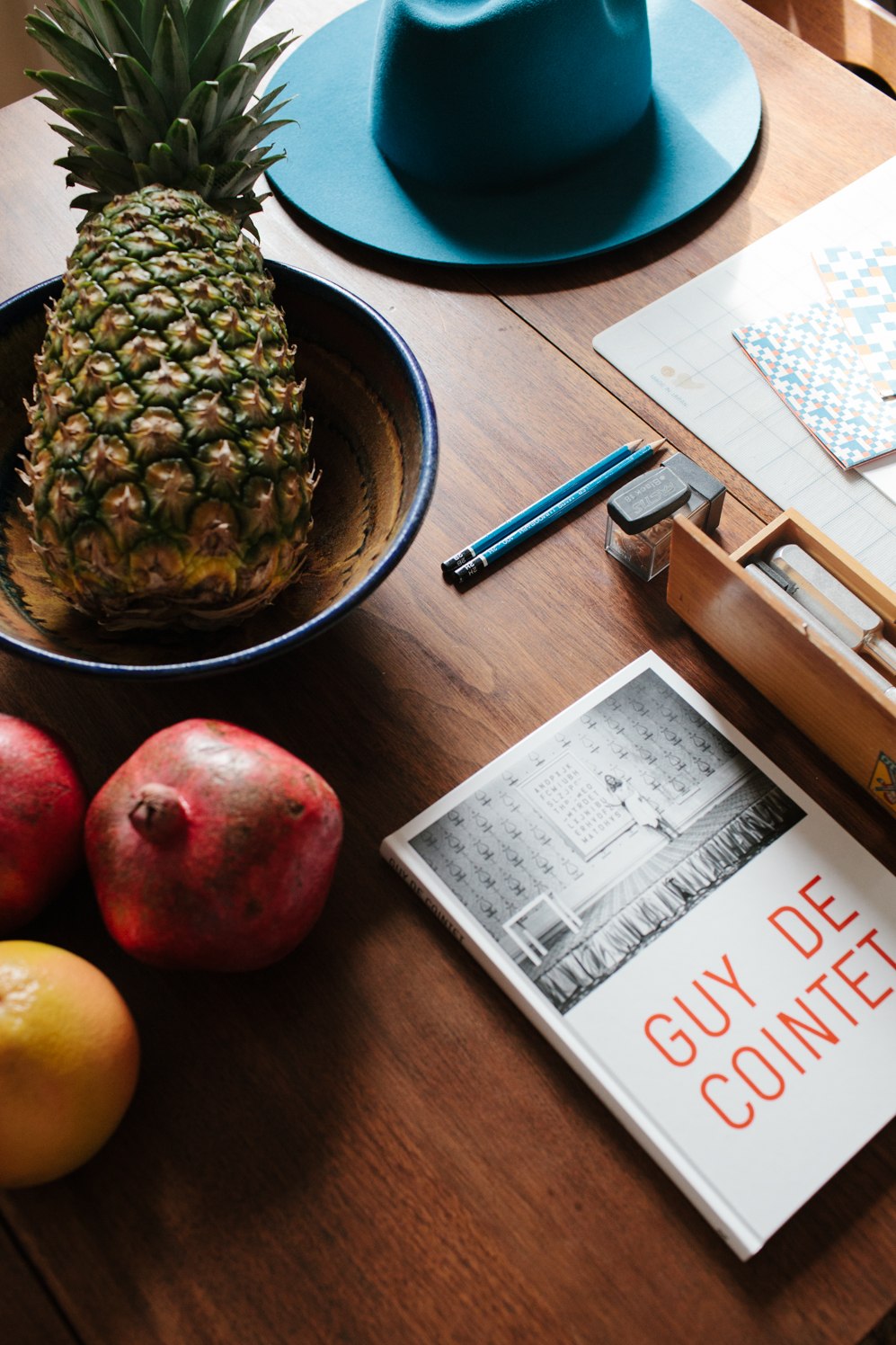

It’s the little details that always count. On arrival a Woo record, “It’s Cozy Inside,” is playing. His kitchen table is spread with ephemera – exacto knives, cut-outs, more magazines, and concept sketches that he used to develop his latest album cover. This could have been an accident, but at the very least it feels fortuitous. Facing the interior courtyard between two rows of buildings his apartment is quiet. This silence is the ultimate luxury – something he is the first to admit – granting him some peace of mind and solitude. Alexis is the type who favors steady immersion; a slow absorption of his surroundings that benefits from a little silent gestation. He drifts within the city’s inner rumblings, purposefully, and with both eyes wide open. It’s all material, waiting to be spun into song.

He makes a habit of attending modern dance pieces, of which he has scored a few. An afternoon at the movies – favorite cinemas in the neighborhood include Film Forum and IFC Center – is another favorite past time. A favorite book shop, 192 Books, and coffee shop, Café Grumpy, is only a few blocks away from his apartment. Same to his favorite coffee shop, Alexis often speaks of other places he’d like to be – daydreaming as healthy mental exercise – but, in the meantime, he seems to have found a special place in New York City.

This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who present a special curation of our pictures on their site.

What’s your ideal working environment?

Time. Time to work on my work. Nature. Fresh air. Swimming. I’m just a slow person. I suppose I’m in New York because I know there’s this chunk of time right now where I have a certain kind of energy and drive, and so I put myself in this place where I know it’s sink or swim, and because there is opportunity here. That is the real reason.

I find I go through very distinct stretches where I hole up to make music, or I socialize to sort of feel that I’m taking advantage of being in New York. However, the truth is I often just like to make music. That’s a side of the music industry or the music world that I’m not in it for. My ideal life would be waking up, having breakfast, having a pot of coffee, sitting at a piano for four or five hours, having lunch, and then doing everyday things. Having that time of day to just work and do things like take walks. I’m always impressed when I have friends who always seem to make room for things like that, even in New York City, because I find it difficult to fit into a 24 hour period.

You’ve spent time on both coasts. Does the East feel different from the West?

Yeah, because there is a feeling in San Francisco of being sort of lampooned off somewhere. I found the artistic landscape to be a bit narrow in scope.

Narrow in what way?

I think there is sometimes, among people there, not a sense of the world “out there” – meaning outside of San Francisco. At the time that really attracted me to San Francisco, but by the end of it, I wanted to be able to talk to people who might have an argument with me because they disagreed about something. Instead of just saying: “Dude, relax, man! Hit this!” I found there to be a passive reluctance to engage with things, to be critical.

What did you find was different about living and working in New York City?

It just became clear there were opportunities and contexts here that didn’t exist in San Francisco. Shortly after I moved here, visual artists asked me to do live scores to their films and modern dance choreographers asked me to compose scores for ambitious dance pieces. Those were things I had always wanted to do. In San Francisco the dominant atmosphere, was house parties and street art. For the first few years I was there, when I was just finding my footing, I worked at Adobe Books and there was sort of a salon like atmosphere of artists and creative people coming through. That was very exciting for awhile, but then, after seeing that things weren’t changing, and that these ostensibly “creative people” were actually quite content to churn out very repetitive and unchallenging work, I knew it was time to leave.

Were these invitations to collaborate part of the catalyst for ARP?

Shortly after I left Tussle, – a group I played in for four or five years – I started experimenting with analog synthesizers and recording things on 4-track cassette. Around that time, Matthew Higgs – of White Columns gallery – got in touch with me and said he was doing this group show, so I came up with a plan that incorporated some of those pieces. From the reception that it got, I thought “Oh, well maybe this is worth actually releasing as a record.” As it turned out, that installation turned out to be the majority of the first ARP record So, at that point, I started taking the process a bit more seriously. But originally when I was doing it, it was really just to do it, it wasn’t with any sort of intentions of making records.

It seems that productive interactions — collaborations, collisions — are central to your creative method. You don’t necessarily lock yourself away, you collage influences from your life. You spread yourself so wide, it seems like when things become ‘music’ it’s almost an accident, established in retrospect.

I like that idea. Maybe that comes from the fact that my interests are quite broad. I’m less interested in the kind of music that I’m making, and more interested in just making it. Does that make sense? In other words, had I met different people at different times in my life, that may have just steered me into a different direction. It’s hard to say. I’d always been writing pop songs and four tracking them, but it took ten years to decide to actually put a record of “Pop” songs out. And, strangely, I had to put out two instrumental synth albums and a chamber music record to feel like I’d arrived at this place where it made sense for me to do that.

Do you feel like you had to earn The Pop Song?

For a long time I thought song was a dead form, which sounds horribly pretentious! But I thought that the song form has lasted for so long that it reached this place where the form itself seemed to be eating itself from within. It’s not that I didn’t think songs were worth anything, it’s that I didn’t feel like I was able to contribute a song that felt relevant in the giant Pantheon of Song. So I went through a process of getting as far from song as possible. That led me towards Minimalist Classical music and 70s Kosmische records and field recordings on to very conceptual, almost invisible sound art , ultimately leading towards things like glitch music. Mille Plateaux, a label in Berlin, and Touch, a UK label, just seemed to be putting out so many incredible records of this kind of stuff – Markus Popp‘s Oval project, SND, Carsten Nicolai, Ryoji Ikeda…

It was just dust and crackles, and I was really into it, for awhile. That’s how far away I went away from song. And then, I think there were places where that stuff connected with some of the more pastoral sides of ’70s German music, and little by little, synths came into my life, and eventually, here I am at the song again.

What’s your intention when you write songs?

With the new ARP album, I was trying to play a kind of connect-the-dots with references. Not to hide behind them as a mask, but to create a little genealogy or archeology. Ultimately though, I think a song has to connect with somebody for real. It’s not just about: “Oh, it sounds like this other person I like!” Those things are there to give people a cookie, but after they eat the cookie, there has to be something else there. They’re simple songs, but I hope there is enough depth and a enough playful experimentation to make it rewarding. But yeah, the songs are drawing on a tradition of songwriters, not so much a singular style of music. It’s not Minimalism or Glam Rock or Prog Rock, per se – though it does include aspects of all three of those approaches. It’s more a tour through a sensibility rather than genre.

What sensibility are you attracted to?

The people whose influence is most obvious, to me, are people who were not necessarily the most obvious but rather artists who were content to pursue their own line of thought that sometimes ran in parallel with cultural trends and sometimes ran in opposition to them. Some of the records they put out were not even well received at the time, but over the course of 30 years, they’ve gained a certain cult following. John Cale, The Left Banke, Spacemen 3, Robert Wyatt. Kevin Ayers is a good example. He was in Soft Machine with Wyatt, and was playing in San Tropez with Pink Floyd, and then he started getting into jazz. They were sort of silly in a lot of ways. There was a bit of a flowery beatnik thing going on, but then he went solo and was writing these songs that were sort of folky and sort of blissed out and idyllic, but also very personal.

It can get a bit too dippy at times but some of his early albums have songs that combine a lazy Syd Barret thing with an almost Nico “Chelsea Girl” kind of thing. To me, he was an example of somebody who said, “I’m going to go live in the south of France or in some rural part of leafy England and just make these songs and do my thing.” I like that. Time tells what really lasts, and sometimes doing something that’s quiet resonates with people.

I do feel like it’s easy to listen to your music over and over again. There’s room to have many different types of experiences with it.

Oh, that’s great! That is definitely one of my hopes. I think that might just be because I try to leave space so that the listener can fill in the blanks differently. If people apply terms like ‘minimal’ to the songs, I think a good aspect of that is implying melodies, but not necessarily playing them. It happens to me. I’ll be making dinner and a harmony will come into my mind of a song that’s on, and then the next time I hear it a different one might come into my mind, and I like the idea that the listener can sort of interact with it in that way.

What’s your creative process for collaborating with others, like scoring films and dance pieces?

It’s really different each time. That’s probably been the most collaborative process, because certain choreographers have very clear ideas of what they’re looking for. Which poses challenges, but that’s also what’s fun about collaborating. You end up doing things you might not have done just by yourself. Really, it’s a case-by-case thing.

Can you give an example?

Jonah Bokaer, who was a Merce Cunngingham dancer. The first time I saw him dance was for a Robert Wilson piece and I was blown away and understood why he was the youngest ever Merce Cunningham dancer. But in his own choreography, he strips dance down to the most minimal movement. It’s really abstracted to an extreme degree. He did an amazing thing at BAM last year with Anthony McCall, who’s a light artist, so that sort of gives you an impression of where he’s at. With me, he wanted planes of sound, like horizontal planes, and nothing melodic. Whereas for me, I was like, “Oh, working with a Merce Cunningham dancer, I can finally indulge myself with one of these chamber ensemble pieces and do my little homage to all these New York composers that I love!” But he didn’t really want that. Instead, it’d be things like one piece of guitar feedback that was looped. I did get to use cello and strings, but in a more abstract way.

With the visual artist Tauba Auerbach, who I collaborated with in May, things were more open. The context was Philip Johnson’s Glass House. A musical performance of mine paired with a sculpture of her’s. We had conversations and both decided we should use the materiality of the Glass House as a point of departure. Glass is most often derived of sand, of course, so she decided she’d make her sculpture out of sand and I decided my piece would, in a sense, start with glass – with clear, long tones – and then over the course of time the sound would, sort of, explode into shards, returning the glass to its source, sand. In this sense though, after those initial conversations, we each had total autonomy.

Do you just have a running list of things you’d like to do? An idea vault?

I think, in the back of my mind, there is a small list of things I would like to have the opportunity to do or contexts I would like to work in, but I prefer if those opportunities present themselves, rather than me, for example, just making a classical chamber record. It’s something I would like to do. I thought on two separate occasions that I would have the chance to do it, but the people involved kept me from indulging. So yes, in the back of my mind, there is a small list of things I hope to do. At the same time, often when I feel I have an opportunity to pursue one of these, they usually become something different. And I think that’s very important, to allow the room to let things evolve on their own terms.

You seem to thrive on collaboration. How does that correlate with your desire to go off into the woods and work in isolation, like Kevin Ayers did?

I hadn’t thought about that. But with the internet being what it is, if I was in the middle of the country, I would still have access to a computer. All kinds of crazy opportunities arise from random emails! That’s how the ARP & Anthony Moore record happened. That’s how scoring Doug Aitken‘s film happened. I can’t tell if that’s a good thing about seclusion as it is now versus seclusion 50 or 100 years ago. That we can sort of have contact with the world if we want. Maybe what’s not good about now is that it’s harder and harder to truly seclude yourself, if you want to. Somehow, you’ll be found.

There’s always a fucking cell signal.

Yeah. Most of the time. Though in New York City, strangely enough, it can be hard to find! So yeah. I think there have been a few occasions where I’ve just received an email out of the blue and that’s lead to a really interesting project. Even if I’m holed up in my studio six months a year, I think there are still opportunities that drop into your lap sometimes.

What was the last thing you saw that struck you?

Probably the Ken Price show at The Met. Price was a sculptor from LA from the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s. His show was a perfect analog to the Turrell show across the street at the Guggenheim at the same time. In many ways, Price and Turrell may have had similar things in mind, but one does it with the sublime in mind, the grandiose, while the other worked with very small objects and yet still conjures a mystical cosmology.

What are the things out on your table here right now?

Designs for the album. There’s still a few things left to do like a tour poster, tour 7″, and tote bags. Strangely enough, because my designer lives in California, I find that drawing things out is much simpler. For the album cover, I came up with a format, and I was like “What if we tried this?” let’s try these five photographs, and he said, “OK cool,” and he sent me one, and then I said, “What if we do a sort of 16mm film dot pattern?” So, when you’re interacting via email across coasts, for some reason it’s difficult to explain in words, so drawing it out was just a much more expedient way of doing it.

Is that what all the issues of Frieze are for?

Yeah, well I was looking for collage material. I used to subscribe. Tussle played a Frieze art fair and we got free subscriptions for a few year. But it’s actually one of the only art magazines that I do end up buying periodically. I tend to like when they talk about things other than art, like music or culture at large or trends in culture or subcultures. The anthropological end of things and not just things that are insular art jargon. Some of the writers, like Dan Fox and Simon Reynolds and Michael Bracewell, I just really like.

What other magazines do you read?

I did use to subscribe to The Wire, and I do still look at it from time to time. I’m less drawn to buying it these days. It’s too close. That’s why I stopped writing about music, too. Sometimes making music and writing about it fucks with the other a little bit. I think I needed to silence that inner critic to make music. I’ve also been thinking about this idea that sometimes you read a review of something, and I often ask myself whether that person makes work themselves. There’s a Renata Adler interview where she says you can’t be an honest critic of something until you’ve tried to be a maker of it. Certainly, I feel I could guess with some accuracy when a critic has clearly never tried to make the kind of work s/he is writing about.

I guess there’s an important difference between being a critic and critical feedback.

Yeah. I read a review somebody wrote about “High-Heeled Clouds” – the first song on the ARP album “More” – where they said it was almost childlike in simplicity. They meant it in a good way, but they kept drawing attention to the simplicity of the song, with this subtext of naiveté or innocence. I wanted to say, “Did you listen to the words?” I can imagine the same kind of person accusing The Smiths of always being depressing when in fact, Morrissey was often hilarious! And that combination, that contrast, can be great if you can achieve it. In the case of “High-Heeled Clouds,” it is actually kind of a sinister song. Not sinister in a horrific way, but the lyrics are portraying a pretty dark person. I like wrapping thorny sharp things in something that’s really palatable.

There are a lot of layers in your work. Layers of sound and layers of meaning.

I think layers are inherent in the best art. But, you know, oftentimes people don’t necessarily pay attention to them. The most obvious thing is usually what’s given the most attention or is the easiest to write about. The most obvious lead sentence is what determines what a review is about.

I see a copy of Speedboat on your shelf. Speaking of layers, how did you come across Renata Adler?

I’d seen it at Three Lives and Company, one of my favorite bookshops, and also at McNally Jackson. It stuck out because it has a really nice Helen Frankenthaler painting on the cover and I’ve always loved her paintings. I also knew the New York Review of Books – whoever is pairing the photographs and paintings with these books is doing a great job! So, the cover caught me and the fact that I kept seeing it on staff pick lists and on display. One day my girlfriend bought it and started reading it and fell in love with it, so I would occasionally leaf through it. It connected with me in the same way as Joan Didion. Somebody who was maybe a little funnier, a little looser.

What else do you like to read?

I go through different periods with what I read. I’m starting to get back into fiction. But most of the fiction I read tends to be older, like Russian and French stuff. For me to actually pick up a book of contemporary fiction, it needs to be recommended by a few friends first. I’m not entirely proud of my recent reading habits, because it tends to be a lot of New Yorker and Harper’s stuff. If I get time at the end of the day, I get to spend time with a fiction book, but most of the day I’m just trying to make music. I try to read a little bit at breakfast, but then I spend a good chunk of the day with music.

I’ve become really taken with podcasts when short on time.

Listening to the radio and podcasts fulfills something different than reading. You’re satisfying something other than listening to the story. You’re listening to a human’s voice read. I love that. I do listen to NPR while I’m making dinner, also Radiolab and Studio 360. That kind of stuff. With news, things are kind of insane these days and there’s a lot I don’t know. A lot I’d like to know. But I feel also quite sensitive to bleak news. I find it difficult to then concentrate on what suddenly seems so much more superficial, like composing music.

Yes, I feel a huge dissonance between what happens in my day-to-day life and what is happening in the world.

That thing I was saying earlier: “Yeah I just want to go France and live a very simple life.” Am I a bad person for wanting that? Sometimes it feels like the privilege to be able to even think about doing something like that is built upon such a foundation of corruption and power that it complicates what, to me, seems like it should be a very simple, decent thing to do. To have a quiet autonomy.

What kind of movies are you attracted to?

It’s hard to say exactly. I don’t think there’s a specific thing I look for. I love Fassbinder. A lot of the French and Italian stuff from the 60s and 70s. Louis Malle, Melville, Agnes Varda, Rohmer, Antonioni. I like Olivier Assayas a lot. Herzog, Ken Loach, Altman, Sidney Lumet, Cassavetes. There are so many. I do feel like the 70s were the peak for American cinema and I love so much of that stuff. Tarkovsky and Nicholas Roeg.

I just saw Blue Is The Warmest Color. For all the controversy about the sex – and I actually thought that was the most distracting part of the movie; I thought it felt voyeuristic and it took me out of the moment – it’s really about so many other things. Class, personalities, different hopes, different realities. I thought it was a really interesting film.

Alexis, this interview and tour of your home has been much appreciated. If you want to find out more about Alexis’ music visit his artist website here or find it on iTunes here.

Photography: Brian Ferry

Interview & Text: Cassandra Marketos