Alec Soth is a Magnum photographer from Minneapolis, Minnesota, known for his long-term projects that capture the spirit of middle America. His breakthrough project, “Sleeping By the Mississippi”, is a collection of photographs of the people and places he encountered along a meandering road trip down the Mississippi River. Since its publication in 2004, Soth has published over 25 books, had more than fifty solo exhibitions, and received numerous awards.

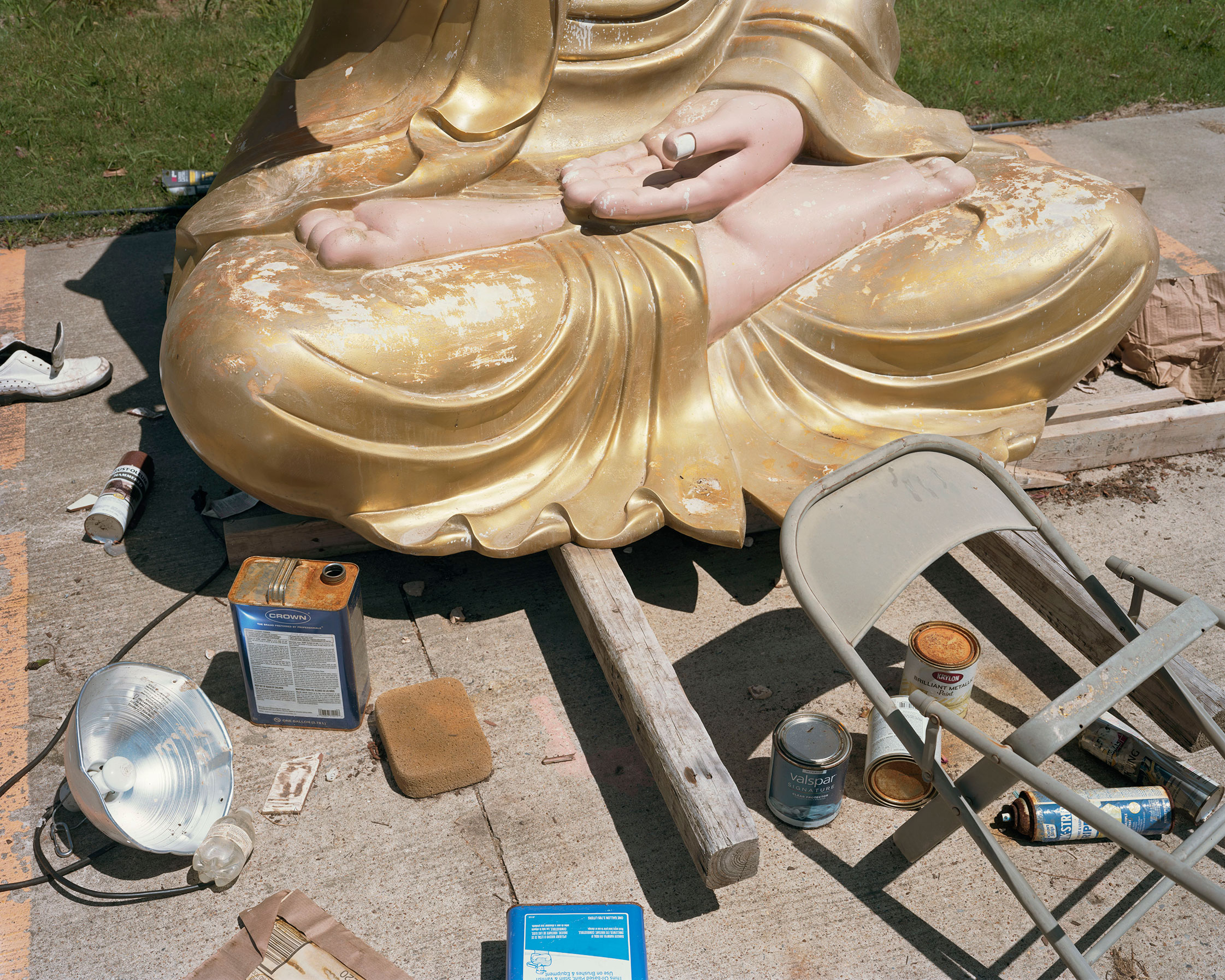

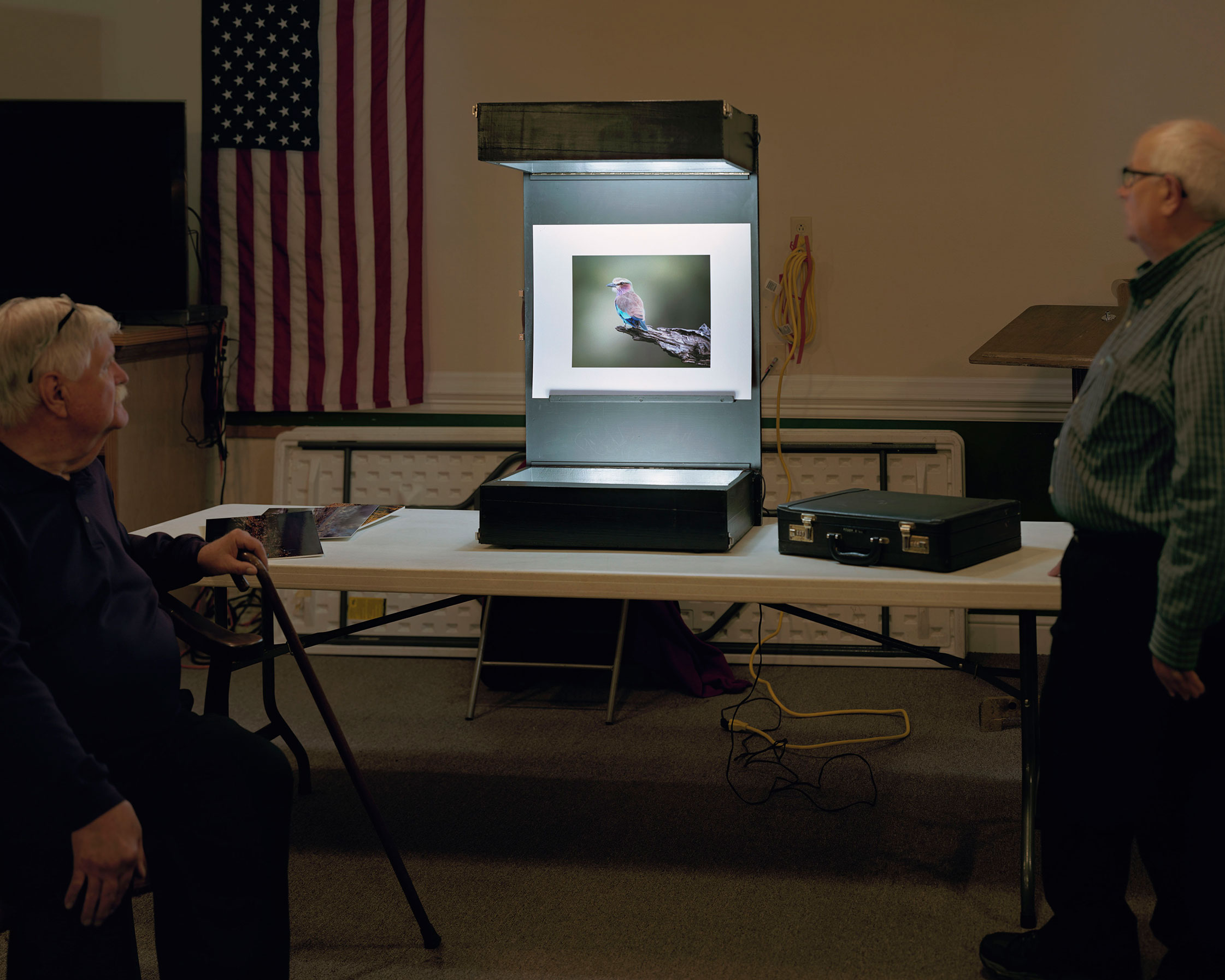

In his latest project, “A Pound of Pictures”, Soth takes a more personal approach than in his previous work. Made between the turbulent years of 2018-2021, what started as following the route of Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train turned into a meditative and, at times, existential reflection on the medium of photography and his own process. With a title inspired by a vendor he discovered selling pictures by the pound, Soth asks: “How much does a picture weigh?”

Ahead of his upcoming exhibition at the Stiftung Reinbeckhallen in Berlin, we sat down with Soth to talk about the project, combating cynicism, and the joys of going out into the world.

-

There’s so much of yourself that comes into this project, and very honest reflections of your process. How important was that for you?

I did want to put myself in the project, but it’s problematic as a photographer because unless you’re photographing yourself, you’re facing the world out there. How are you supposed to pour your heart out when dealing with the visual world? Similarly, when I photograph another person, how am I supposed to get into their heart when I’m dealing with their exterior? It’s this very challenging thing about the medium of photography: the limitations of it.

-

You mentioned that when you started the project, you had kind of a breakdown about whether you felt you could take a good photograph anymore. Which was the first image you saw that made you feel like you were back on track?

I took some pictures in Michigan during my complete falling apart, and they’re terrible pictures. They communicate nothing. I thought: “Maybe I’m just going to stay here in this little town in Michigan, and I’m just going do a whole project here in this little place.” I was on the brink of quitting, and then I decided to go to Memphis. I thought, “I’m just going to try. I’ll just see what happens.” It was there that I kind of pretended to be a younger version of myself. It was almost as if I was a young person trying to be like William Eggleston. I took some pictures in Memphis that really made me feel better. It helped me move forward.

-

I wanted to ask you about the picture you have on the back of the book.

That particular picture (see below) was very important for me . It’s a picture I love. One could say it is ethically problematic, but I don’t feel it. I feel good about it. There was just a feeling in the air. I think I turned a corner of acceptance with that one. I don’t attach labels to her, and that’s where I like being as a photographer, where I’m not attaching labels to things as I look at the world.

-

You started out the project in one way and then changed directions. I wonder if you could speak a little more about that: on the one hand, overcoming self-doubt and regaining confidence in your work, but also admitting to yourself when something just isn’t working?

I mean, I’m no master tightrope walker. I have to relearn it every fucking time. I can throw out pearls of wisdom all day long, and none of it matters until I go out in the world, start doing something, and then get feedback on the work itself. That tells me if I began to listen where the project is supposed to go. But boy, it’s not an easy process. I always read those interviews with novelists talking about how [with] every book, you start all over again. It’s the exact same thing with me. And I’ll think that, “Oh, I’m a master photographer, I’ve got this figured out” which is the death of it. That’s when you get into big trouble.

-

Constantly questioning yourself, setting new challenges, and learning new things along the way- I think that’s definitely important.

You have to see things through, but you must also be willing to change. It’s a balance, and it’s push and pull. There are not any guidelines as to what you’re supposed to do. You just have to run with it and see. I have abandoned projects in the past without making something out of them. Sometimes that has to happen. I always have the same feeling that photography is so easy, as a medium, and then it’s just incredible how hard it is. It’s so easy to take a picture, and it’s not even really that hard to take a good picture. But to put them together in a meaningful way, it’s, like, impossible.

-

In your book you say, “When burdened by the feeling that there are too many photographs in the world, I ask myself if there are too many flowers.”

Even in a pre-digital age, I think cynicism was easy to fall into. Thirty years ago, it could have been like, “Why would I take pictures that are not gonna help abortion rights?” We become cynical about what we do, and it’s understandable. It’s just, it doesn’t get anyone anywhere. Learning to let go of that cynicism, at least for a little while, is really important. Nobody is more cynical than art students. They’re judgmental, and that’s fine, and it’s fun, but it can overwhelm the system. Often because of social media, it seems like it’s worse now. I don’t know if it is. Maybe it is, maybe it isn’t, but I think there’s always been this feeling of too many pictures.

-

You visit some abandoned spaces and document the photography that’s left behind there. What are your feelings as a photographer when you go to a space, maybe not knowing anything about its previous inhabitants and seeing so many images and memories that are abandoned or forgotten?

Photography, for me, is this paradox. We’re trying to preserve things, trying to stop time, which is why you do it on a fundamental level. So when you see abandoned photographs, it feels awful, almost the same as for me throwing away a negative, which I never, never do. But I resist that feeling. That is not what photography is supposed to be. Yet, it’s inevitable because everything’s falling apart. Everything disappears.

There’s this surface of the image, and then there’s all this stuff beneath.

-

In this project, you revisit a few locations, both from your own work and from the work of other photographers. How does it feel when you go back to those spaces?

The way we carry history in our brain is just fascinating. There are certain books, like Robert Frank’s “The Americans”, that I don’t pull off the shelf daily, but I carry a little with me. So then, if I revisit the places he’s photographed, I’m carrying that history, looking at the world, and noticing how they don’t match up and when they match up. There’s this surface of the image, and then there’s all this stuff beneath. That’s our own experience, everything that we bring to it, our own memories, and that fills it up with the meaning. But it’s different for everyone.

-

Your exhibition is going to be opening in Berlin. What is the importance of having your work in a physical space and having physical interactions with your work?

As a photographer, there’s this continual revelation that is going out in the world is a good thing. That the world is more complex, more interesting, more rich than I think it is. That’s because I enter into the physical world. The same is true with art. We’re constantly consuming it in this digital form, which is perfectly fine. But when you go to an exhibition or a bookstore — you pick up a book, you’re in that space. There’s such a value in going somewhere to get a book and then taking it home to your bedroom, or going to an exhibition, and encountering these larger prints. Over and over, I’m like, “Oh wow, this really is different”.

Make sure to visit Alec Soth’s exhibition “A Pound of Pictures” which opens on Saturday, 23rd July, at the Stiftung Reinbeckhallen in Berlin.

If you’re interested in learning more about photographers’ inspiration and processes, check out the Friends of Friends archive of photo essays.

Interview: Lucy Pullicino

Images: Alec Soth / Magnum Photos, courtesy Loock Galerie.