No need to repeat the mantra “print is not dead” any longer: Despite progressing digitization, it’s become ever more apparent that print magazines are not dying out.

Quite the contrary, they’re actually becoming both more diverse and more sophisticated. For Ricarda Messner, whose magazine Flaneur is often described with a language advocating a certain slower pace, analog and digital are far from mutually exclusive. Her new project SOFA is considered to be an empathetic zone that connects physical and digital sofas and the discussions that take place there. The first edition with its trashy, high-gloss look addresses Gen Z, the current generation of teenagers, who are so often accused of spending every free minute on their phones. But in truth, today’s teens have plenty to say. So it’s easy to see why Ricarda and her colleague Caia Hagel have invited Andy, a 16-year-old, to act as co-publisher for SOFA‘s debut issue. They found her on Instagram.

“Flaneur and SOFA are obviously very different—but that’s exactly what I wanted to achieve.”

Meanwhile, the team behind Flaneur continues their biannual search for the street that will serve as the centerpiece for their next issue. How does Ricarda manage both projects at the same time? “By now, I’ve learned quite a bit about a magazine’s production process. However, I still mostly depend on my own intuition.” And on fortune cookies. Ricarda grew up just down the way from Kantstraße, which is often described as Berlin’s Chinatown. While that may well be the source of her obsession with fortune cookies, it’s very definitely the place where she started to make magazines three years ago. “I still try to reconstruct the moment in my mind that actually led me to start making magazines. Only gradually, the individual puzzle pieces begin to fall into place and reveal everything that actually factored into that decision. Much of it is undoubtedly due to the feeling of satisfaction that I felt when I printed my completed 160-page final thesis and held it in my hands for the first time.”

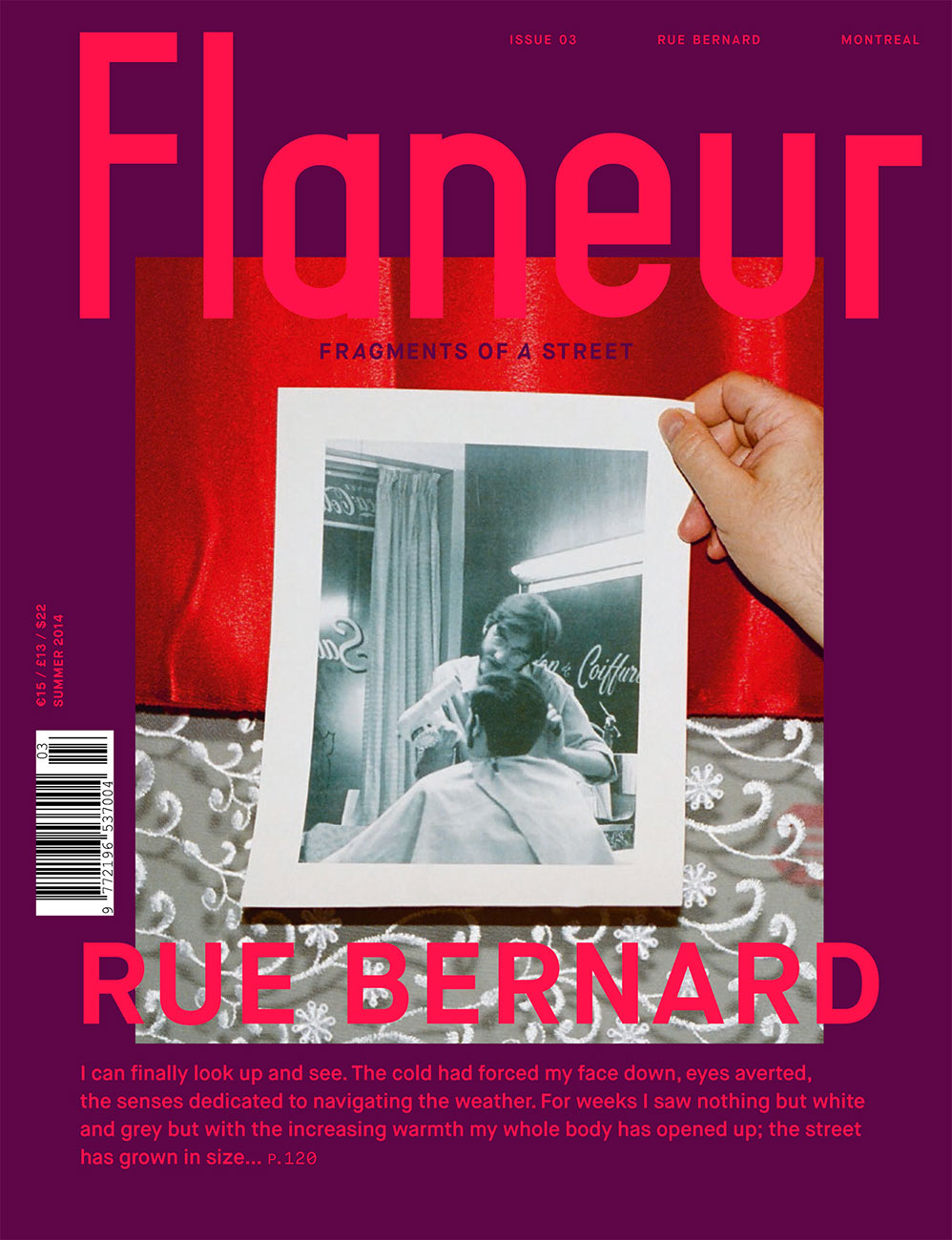

Seeing her own magazine printed constitutes that same sort of moment in which all of the work and effort finally pay off. Above all, it’s a feeling that can only be experienced with print. Things published online have a tendency to quickly disappear again into the depths of the internet—there’s no place for it on the bookshelf. In contrast, bringing a print magazine to life and properly conveying its objective both require an immense amount of patience. It usually takes a few issues before it starts to receive some attention and distributors and readers begin to grasp its concept. Up until its third issue, Flaneur was forced to fight against the idea that it was a kind of city guide. “We don’t want to promote places in the traditional sense. Flaneur represents a different way of experiencing a place and is actually anti-touristic.”

“Flaneur represents a different way of experiencing a place and is actually anti-touristic.”

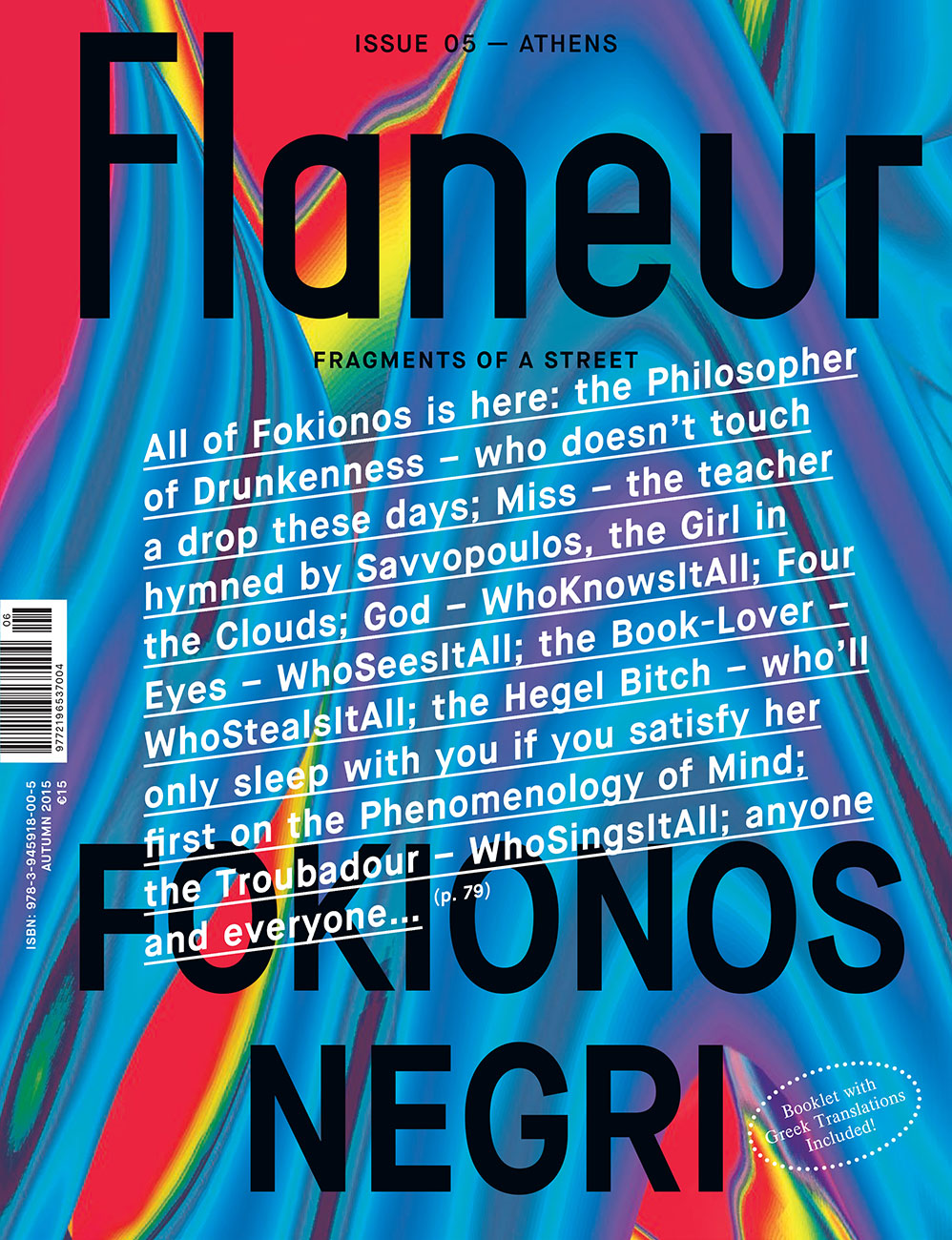

To immerse themselves in what’s perhaps so often missed from a touristic perspective, editors-in-chief Fabian Saul und Grashina Gabelmann, who developed the idea for Flaneur alongside Ricarda, always spend two months on location in each city. The designers from Studio Yukiko then join them for a few days, as the visual aspect of each issue is influenced by the place it depicts. How do cities differ from one another typographically? What catches one’s eye? Both art directors interpret their impressions in the appearance of the nomadic magazine. At this point, they function as a well-practiced team and Studio Yukiko is taking over responsibility for the design of SOFA as well. “The two can work well without a lot of input—which isn’t always the case with designers. When I suggested doing something completely different for SOFA, they were immediately on board. I’d have to have a good reason to work with any other designers.”

Ruthild and Wanda Spangenberg from the Bücherbogen at Savignyplatz were some of Flaneur’s first supporters and immediately added SOFA to their collection as well. The specialist bookshop for architecture, art, design, and photography has resided in the historic S-Bahn railway arches at Savignyplatz since 1980.

Berlin, Leipzig, Montreal, Rome, Athens, Moscow and soon São Paulo—with each city visited by the Flaneur team, a new network of relationships forms and mainly develops during their time on location. When the magazine is finally printed and ready to launch, they head back to the selected city where it all got started and where the people reside that chose to share their stories with Flaneur. The direction that Ricarda and her team pursue varies from issues to issue. Cities are complex and each of them is complex in its own way. This becomes clear the further they take Flaneur outside of Europe. Once a city is selected, the search for “their” street begins and the criteria for that is different each time: “We don’t usually know what we’re looking for.” Letting go and acting intuitively has always paid off: “The exciting part is that this initial gut feeling is always confirmed over the course of researching the street. At the same time, we don’t feel the need to share something that’s generally applicable to the whole location. We collect fragments and let the street tell its own subjective stories.”

“When we told Andy, our 16-year-old co-publisher that SOFA was going to be printed, she completely freaked out. ‘A REAL PRINT OBJECT?!'”

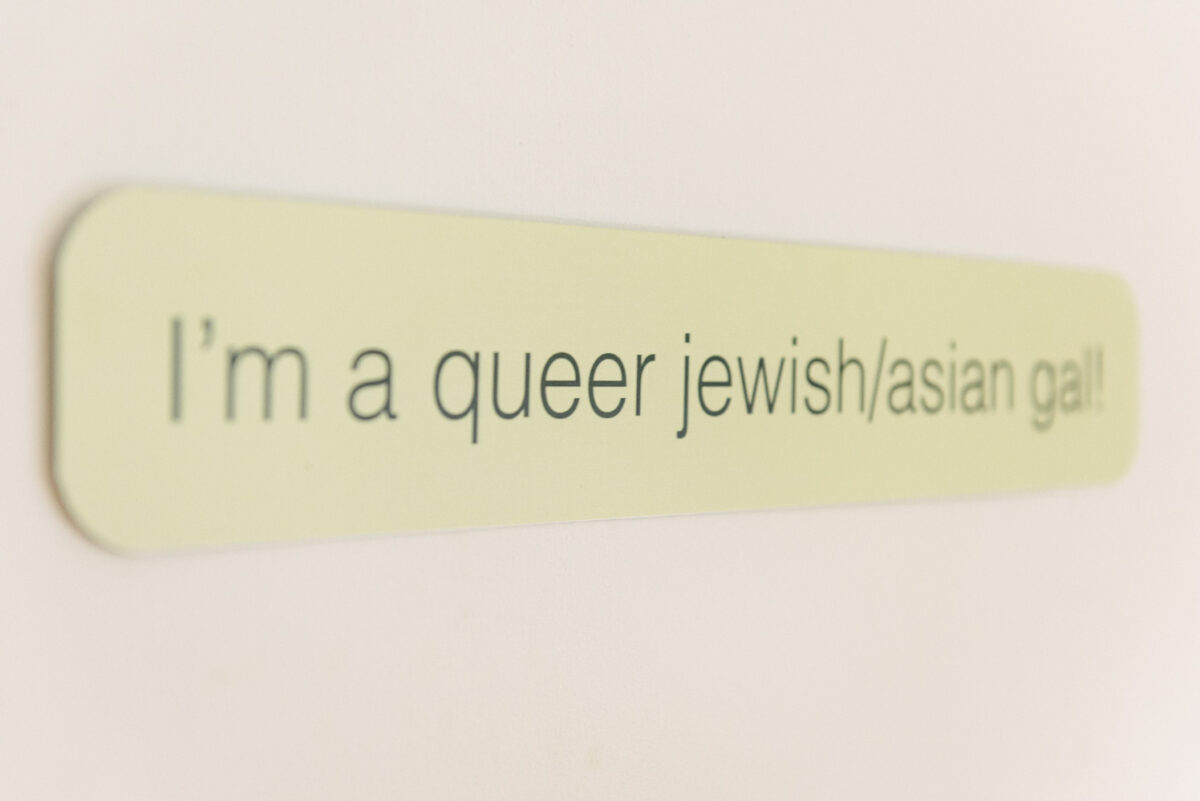

Now with SOFA, Ricarda is heading down a different path, “Flaneur and SOFA are obviously very different—but that’s exactly what I wanted to achieve, it might even be my signature of sorts. I don’t want to classify my work too much. My style should stay pretty open.” Ricarda’s personal creed “Publishing Dreams” (words that take center stage on the site of her publishing house editionmessner), unites the two magazines. Personal stories are the focus of both projects and there’s no pretense of completeness or in particular of condensing something that’s complex. SOFA will also have to confront certain misunderstandings with its first edition: “We are not a teen magazine.” Even though the look of the first edition may lead people to believe otherwise. There is, however, an entirely deliberate purpose behind that: “With SOFA, we want to create an emphatic zone in which no one is disparaged for what he or she feels or says. Because our goal is to understand how things develop and where divergent perspectives come from. SOFA also plays with the preconception that anything with a trashy, glossy appearance must be devoid of depth.”

The idea for the magazine came about with author Caia Hagel, whom Ricarda met during work on Flaneur‘s Montreal issue. On the sofa, of course—the place where people say what they really feel. Whether it’s a physical or a digital sofa, face-to-face or in a chat, it makes no real difference to them. Ricarda and Caia have cultivated an online friendship that despite the 6000 kilometer distance between them, is as wide-reaching as a relationship anchored in so-called real life. “Over the last few years Caia has contributed to a lot of my interests. We exchange ideas on all platforms, Skype for hours. SOFA reflects the type of friendship between Caia and me.” Those who still believe today that online friendships are only superficial, perhaps also believe that today’s teens don’t know anything outside of internet. SOFA addresses this as well: The idea of dismantling seemingly unreconcilable contrarieties and entrenched prejudices. “When we told our 16-year-old co-publisher that SOFA was going to be printed, she completely freaked out. ‘A REAL PRINT OBJECT?!'” Like so many people her age, Andy Conrado maintains a strong presence online. That, however, should not lead us to the conclusion that today’s teens have no use for print products. “Gen Z is constantly confronted with the notion that they spend their lives staring at their phones and as such are unable to understand anything with meaning that goes beyond that. I’m more of the opinion that digitalization has strengthened their desire for something tangible.”

“I’m more of the opinion that digitalization has strengthened Gen Z’s desire for something tangible.”

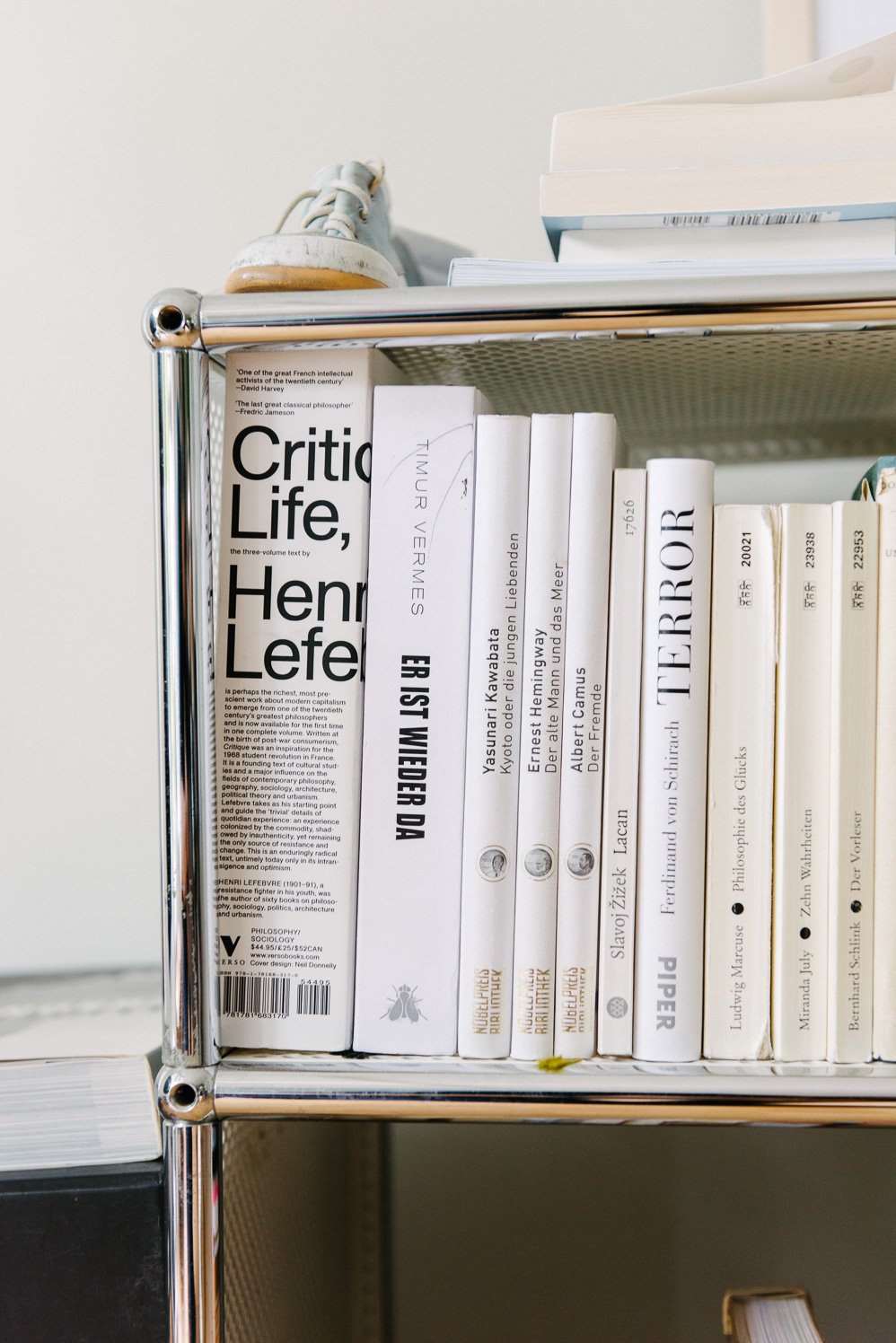

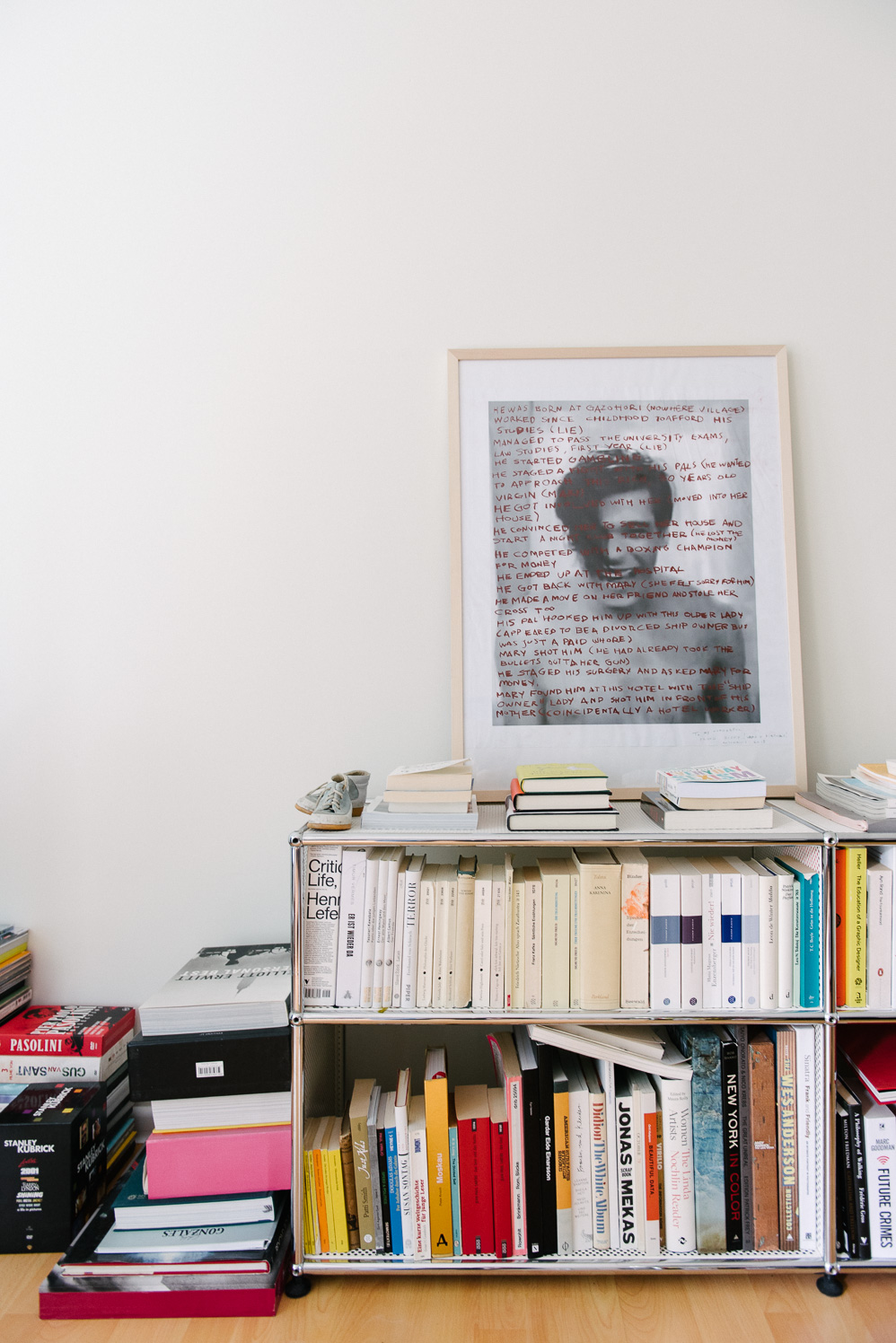

For SOFA, Ricarda is able to draw on her own experiences with Flaneur. In the last three years, there’s been plenty to learn when it comes to production and sales. “Now we even make production schedules for Flaneur“, she jokes before adding: “I hate Excel”. SOFA is easier to produce technically and costs only 6€. “Many magazines are similar in that they usually cost between 15 and 20€. I wanted to make a magazine that doesn’t constitute such a difficult purchasing decision.” As a magazine that people can just pick up and take with them, SOFA has taken some inspiration from the supplemental material of big newspapers. Although it is a bit thicker. There’s an evident influence from the magazines of Ricarda’s youth, like Bravo, for example. Apart from that, Bloomberg Businessweek and The New York Times Review of Books count among Ricarda’s favorite magazines while Indie classics like Pin-Up, the British magazine Mushpit and Playboy with its recent design overhaul can also be found on her shelves.

How does a young woman who started making magazines based on a gut feeling deal with being listed in Forbes as one of the 30 most influential people under 30 in the international media sector? Ricarda probably would have preferred to read this prediction in a fortune cookie. “I still find it difficult to market myself and to be proud of my work.” When she founded Flaneur, Ricarda was 23 years old and was mostly confronted by male counterparts over the course of its development. “At the time, I wasn’t aware of what it meant to do all of these things as a woman. But then these repetitive patterns became noticeable and the question arose of how one actually cultivates professional relationships with men. It can be quite exhausting when people are more focused on the young-woman-bonus and not on the quality of the work itself.”

Studio Y-U-K-I-K-O

“It can be quite exhausting when people are more focused on the young-woman-bonus and not on the quality of the work itself.”

Ricarda’s personal definition of success is mostly derived from the feedback received by her magazines Flaneur and SOFA. Due to the variety of things that she does, she sometimes finds it difficult to see her own skills. She fell into a lot of it without ever having actively determined the course herself. With such a varied career and having spent so much time traveling, it’s hardly surprising that Ricarda has always lived in the same neighborhood in Berlin: “I like this consistency. My apartment and the area it’s in are a constant that I can use to take the measures of the changes in my life.” Aside from a short stint in New York, Ricarda has spent her entire life in West Berlin. Today she lives in exactly the same apartment in which she celebrated her first birthday and in the same street in which her parents and grandparents carted her around in her stroller: “In that sense, it’s almost ironic that I make a magazine about different streets.”

Thanks, Ricarda, for sharing your sofa and showing us your neighborhood. We’re looking forward to seeing the next issues of Flaneur and SOFA. Keep up with more of Ricarda’s publishing work at editionmessner and Hungry for Fortune.

This portrait was produced in collaboration with USM as a part of the ongoing series, “Personalities by USM.”

Text:Vanessa Oberin