Acclaimed British non-fiction filmmaker Kim Longinotto traveled to Italy’s very south to tell a rather different story of liberation.

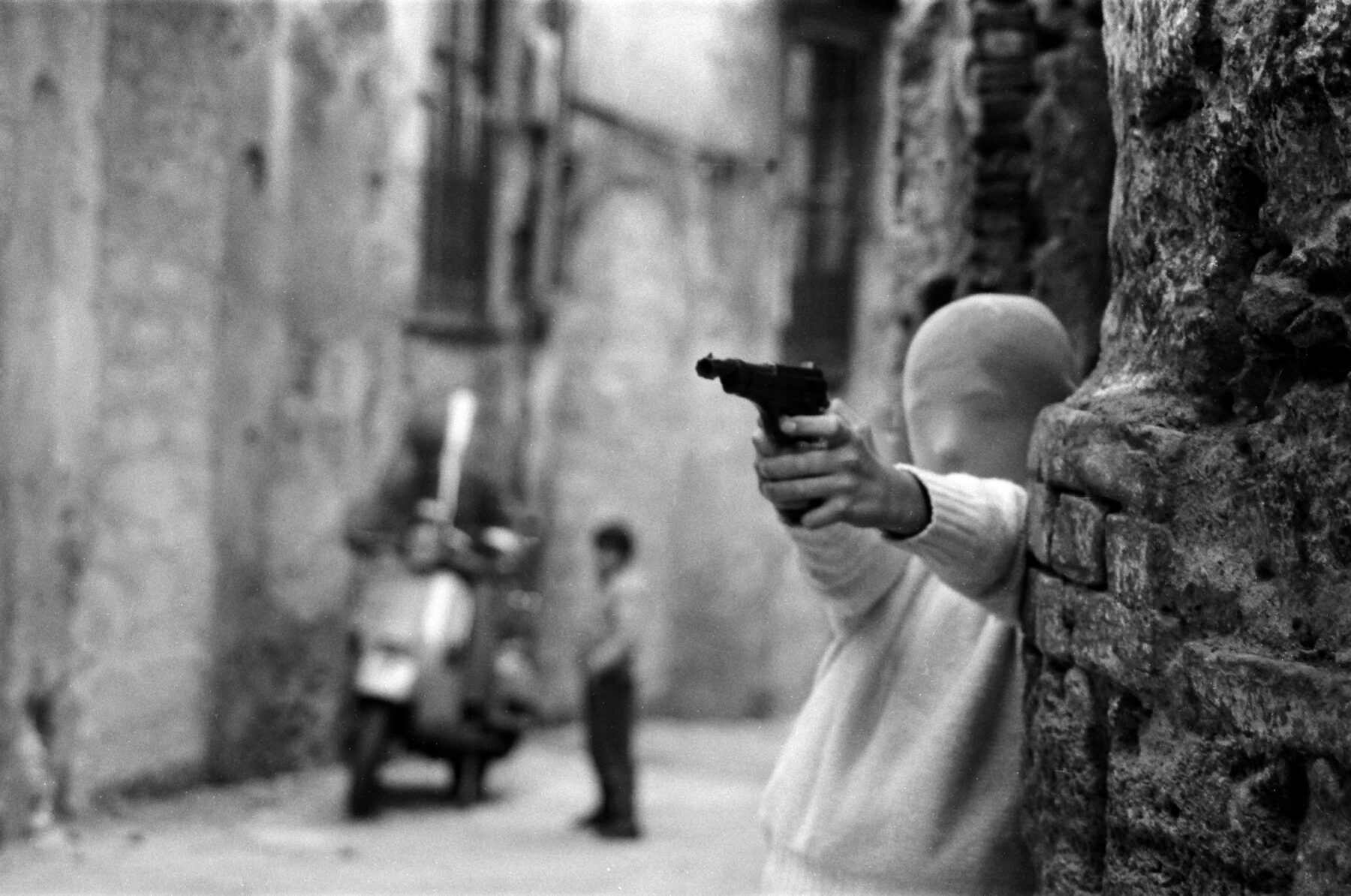

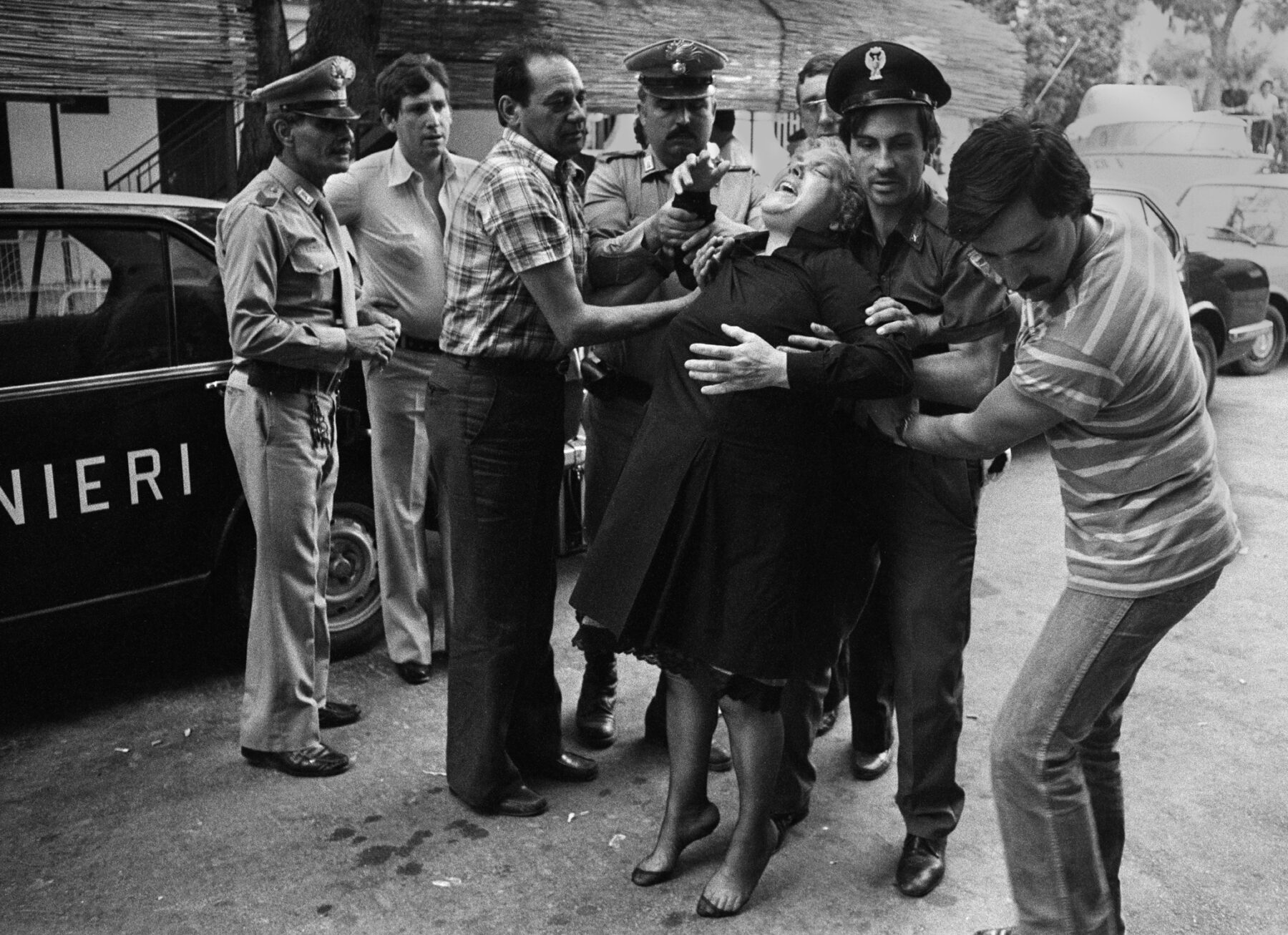

In the hands of a less gifted director, Shooting the Mafia would feel like two documentaries from opposing camps for the price of one. Longinotto though creates a unique tapestry of intriguing images via old home movies, vintage melodramatic Italian films, old footage of Sicily, Letizia’s stunning photographs, local news as well as international reports, and hours of original material she shot herself. Longinotto smartly juxtaposes the life of photojournalist Letizia Battaglia with the rise (and fall) of the Cosa Nostra in the second half of the 20th century in Sicily—and not because her own artistic vision commands it—but because these two stories are inevitably intertwined in the realms of history.

“I know for a fact that a few voices weren’t too happy that I basically tell two stories at the same time,” says Longinotto. “They didn’t like the stuff about Letizia’s youth and Falcone and the Mafia,” she goes on to explain. “But how can you simply drop these issues when her best and most remarkable work is so strongly connected to these issues? It’s as if you don’t understand what was going on in Italy at that time and what she stands for. It’s simply not the right subject to produce art for art’s sake. So maybe it’s best to watch Shooting the Mafia by simply letting go of certain expectations, since you have to be able to dream around the edges of it.“ It is not particularly surprising that the editing process took nearly nine months.

“Stylistically, Shooting the Mafia takes a break from classic documentary filmmaking.”

It’s an understatement to say that Letizia Battaglia is a force of nature. Born in Palermo in 1935, she got married aged 16 in order to break away from her strict parental home. But once married found her free-spirited self was abused once again in an unhappy marriage that resulted in three kids. Determined to fend for herself, she later sank her teeth into photography to get away from her husband, but it wasn’t until 1974 when her career began rapidly picking up speed as she started to capture crime scenes of Mafia hits for Palermo’s left-wing newspaper L’Ora. Battaglia might have photographed a very wide spectrum of Sicilian life throughout her impressive career, but her particular depiction of vicious violence caused by organized crime is what made her a household name within the contemporary art circuit. Her haunting, grainy, black and white imagery have captured the Mafia’s assault on civil society. She eventually stopped taking such pictures in order to officially join the Green Party, for which she held a seat in Palermo’s city council between 1991 to 1996.

“Letizia didn’t enter photography with a special kind of manifesto,” Longinotto explains, “she actually entered photography to get away from her husband. She isn’t necessarily someone who meticulously plans things—she’s more of the type that consciously falls into things. Having said that, I think that regardless what she has achieved in politics and with her heavily awarded photography, she’s slightly embarrassed by her own life, definitely very emotional about it,” adds Longinotto. “I have to admit that I actually love the fact that I met her at this time of her life, because she (in the film and in reality) represents hope, love and resistance. It’s the exact opposite of the Mafia, which is all about rules and hierarchy and traditions.”

As a veteran filmmaker, Longinotto has a long history of portraying women who fell victim to oppression and society’s misguided allocation of roles. From Shinjuku Boys (1995) which explores the life of three transgender men in Tokyo, to The Day I Will Never Forget (2002) that deals with female genital mutilation in Kenya, and Pink Saris (2010), which depicts violence against women in Uttar Pradesh, to name just a few of her twenty full-length features. It’s easy to see why she chose Battaglia as the main subject of her latest documentary. Both Longinotto and Battaglia share a common indignation and sensibility for all the many unrighteous acts life throws at us at any given time, and both are passionate about their system of values.

“When you’re lucky enough to meet someone whose private life is so singular, why not focus on this in all its manifold facets?”

Kim Longinotto is a British documentary filmmaker. Her latest work, Shooting the Mafia saw its European premiere at this year’s Berlinale.

Text: Sven Fortmann

Photography: Jenny Peñas