Transdisciplinary curators and artists Lukas Feireiss and Matylda Krzykowski sit down to discuss the importance of working between art forms, translating culture into the digital sphere, and why we shouldn’t feel pressured to remain one sector for our entire careers.

“Curation” is defined by the Cambridge English Dictionary as the act of selecting and caring for objects to be shown in a museum, exhibition, or to form part of a collection. Put like this, it sounds incredibly simple. However, the role of the curator is constantly evolving. In recent years, curators have come to be seen as artists with creative practices and approaches of their own, rather than mere presenters of artefacts. The term can also be used by people who are at a loss for a better one to describe their varied, ever changing careers.

Two such curators are Lukas Feireiss, whose eponymous studio “provides overall conceptual development, design and implementation for diverse formats of knowledge dissemination and visual communication,” and Matylda Krzykowski, who works across the fields of design, architecture, art, and performance. Among other collaborative projects, Krzykowski notably co-founded Depot Basel, a place for contemporary design which ran until 2018, as well as the curatorial initiative Foreign Legion, which Friends of Friends interviewed her about back in 2018. Based between Berlin and Basel, Feireiss and Krzykowski are also firm friends and frequent collaborators.

This story is the first episode of Insights, Friends of Friends’ new content series bringing together leading visionaries to discuss their opinions and perspectives on the industries they work in.

Krzykowski, who describes herself as preoccupied with “developing formats for cultural and commercial sectors,” was attracted to the field of curation due to a desire to “have an excuse to get in contact with people. I’ve made my own school through curating,” she says, reminiscing about her time studying in the Netherlands. “I was underwhelmed. I expected so much but the school system didn’t allow for the experiments I imagined.” To make up for what was missing, she founded the blog MATANDME, started contacting prominent exponents of the art and design field, and doing studio visits. Among the first people she reached out to were the architect and author Mark Wigley and Frame magazine’s Robert Tieman. “I approached them and asked them to take part in a drawn interview: I asked them three questions and they answered with three drawings: a drawn interview. That was when I realized that if I had a solid format I could lure people into my work and learn so much from their interesting, and sometimes uninteresting, insights.”

Feireiss, on the other hand, never intended to become a curator: he fell upon the profession after a gallery invited him to create an exhibition on the same topic as a book he’d published. “I did a couple of exhibitions like this. After the third, I realized that I was basically just putting the book on the walls. I had a totally 2-dimensional idea of curating. I realized that the space I was working in was so important, and that I really needed to think about the entire exhibition as an environment that I was responsible for.”

“I realized that the space I was working in was so important and that I really needed to think about the entire exhibition as an environment that I was responsible for.” – Lukas Feireiss

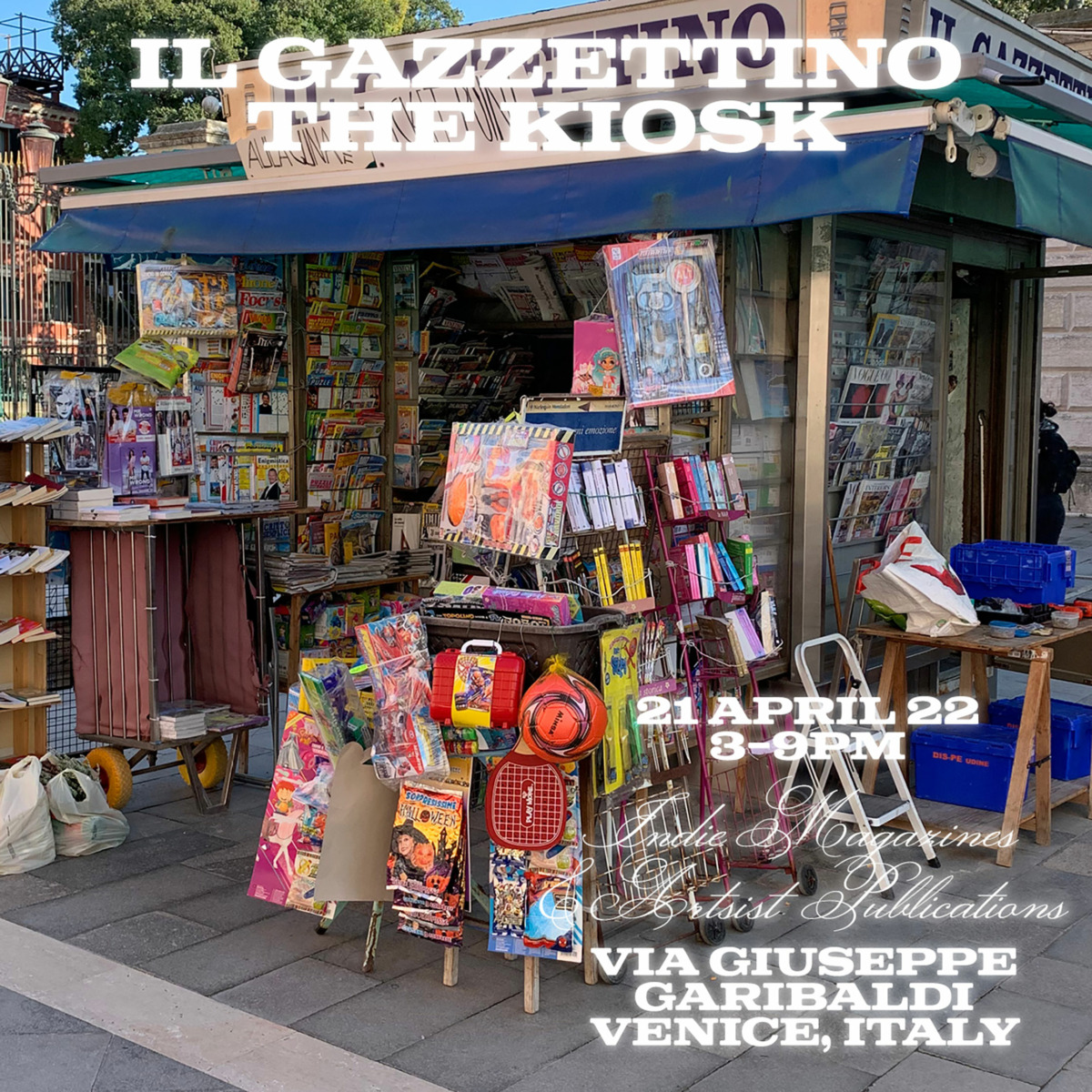

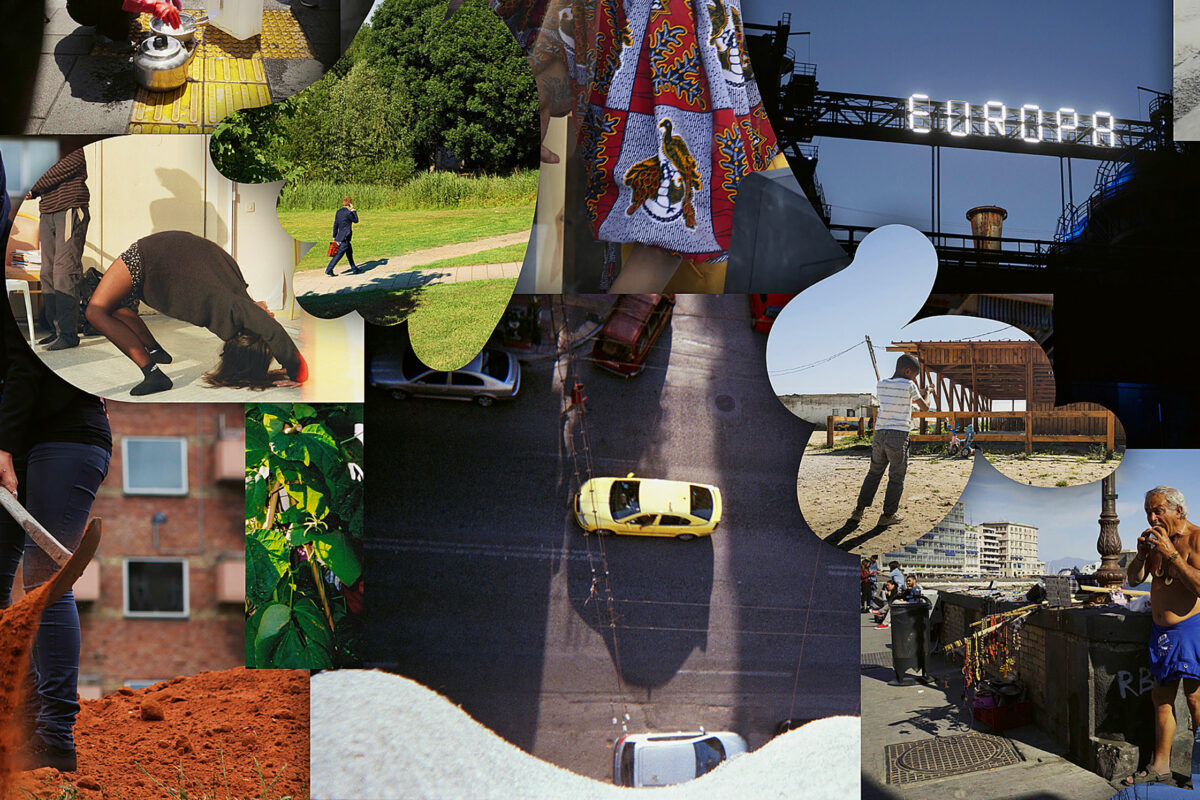

The concept of creating an environment is evident in one of Feireiss’ recent exhibitions, ‘Living the City,’ which he created in collaboration with Berlin-based design office TheGreenEyl and architectural theorist Tatjana Schneider. Exploring the notion of the European city and the people and stories that inhabit it, “the idea was to create a parallel or alternate world, which the visitor enters, engages, and has a tactile experience with,” says Feireiss. Like many other exhibitions, ‘Living the City’ was translated into an online, virtual exhibition due to COVID 19 restrictions. Since then, Feireiss has worked on many curatorial projects including a series of events dedicatd to the organization of knowledge spaces and spatial knowledges for the Bundesstiftung Baukultur, a curatorial research installation that speculates upon the content of three iconic counterculture publications about self-build architecture published half a century ago and was created in collaboration with Swiss architect Leopold Banchini and exhibited at the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale (2021). Earlier this year, on occasion of the 59th Venice Art Bienniale, Feireiss also transformed a small kiosk in Venice into a discursive platform for indie magazines and artist publications from around the world.

Much like ‘Living the City,’ one of Krzykowski’s exhibitions, ‘Total Space’—a contemporary design installation created in collaboration with Damian Fopp from Zurich’s Museum fur Gestaltung—was forced to respond to the digital realm. “We wanted to explore the idea of designing spaces and environments rather than singular objects, which a lot of designers we talked to said they were interested in,” she says. Five international and intergenerational design studios participated in the project. “We borrowed familiar tokens from digital space: a Wikipedia entry as a curatorial text, an interpreted cursor hand, and the blue color from our operating systems.”

Conversations around art and culture transitioning into the online space, and the other way around, have been taking place for many years, and have become more relevant as a result of the pandemic’s heavy limitations to in-person experiences. Yet Krzykowski believes that we shouldn’t draw such clear distinctions between the virtual and physical realms. “I don’t do it, and I know the generation after me doesn’t do it.” Krzykowski’s project Desktop Exhibition is a key example of her investigations in this area. First developed in 2017, it is a presentation format in which the curator clicks through files on her desktop, guiding visitors through the exhibition in a manner akin to that of walking through a physical space. More recently, “while I was working on ‘Total Space,’ Alessandro Belliero from the design studio Sucuk & Bratwurst said to me that the internet is also space. I really liked that,” she says. “He underlined that the spatial elements of their contribution to the exhibition also had to work online, because after the physical installation has gone, the only thing that remains is the online documentation. The internet never forgets.”

On the other hand, Krzykowski notes that there is danger of people thinking that they can just make a digital replica of the physical world, not realizing that the internet is its own medium. “It’s more about how you can translate content into something that can be perceived, viewed, and enjoyed. The question is: how can these ideas that happen in the natural world be translated without being a one-to-one replica?” Feireiss agrees, adding that “this continuous exchange and chain of translations is what drives culture forward.” The impact and influence digital technologies have on creative processes today is also a central theme of Juxtapositions, a public lecture series held at the Berlin University of the Arts, during which Feiress led in-depth conversations with Krzykowski and other cultural producers, such as Tabita Rezaire, Kandis Williams, Katja Novitskova or Hans-Ulrich Obrist, to name but a few.

Aside from the rising importance of the digital sphere, other important shifts in contemporary culture include globalization and cross-cultural collaborations, both of which have resulted in a greater awareness of the need for diversity and inclusivity in creative practices. “It’s a given for me to try and get as many different voices to be heard through my projects. That means different backgrounds, fields of expertise, cultures, genders, and so on. It broadens the discourse and allows for multiple readings. It’s also about making new pathways of knowing through contradiction and seemingly impossible combinations.”

Feireiss is also “obsessed” with encouraging dialogues between different generations. “There’s so much knowledge in older generations that is lost. Bringing them back into conversation and seeing how young people can be inspired by someone who was in their prime 50 years ago, sparks something really interesting.”

“There’s so much knowledge in older generations that is lost. Bringing them back into conversation, and seeing how young people can be inspired by someone who was in their prime 50 years ago, sparks something really interesting.” – Lukas Feireiss

Krzykowski’s approach to inclusivity is much more mathematical: together with Vera Sachetti, with whom she also runs the curatorial and spatial initiative ‘Foreign Legion,’ she has developed a methodology called the 50% rule. “In every project, or everything you do in life—even just inviting people for dinner—you should try not to just invite people you know already. If 50% of your invitations are to people that you’ve never worked with, you won’t just stay in your limited network or bubble.” While the idea in principle seems simple, Krzykowski says that you need to formulate set methodologies in order to inspire other people to apply them. She and Sachetti are also working on a book underlining the long term effects of methodologies. “It’s like writing science fiction: when you develop something today, you have to think about what the consequence of it will be in the future.”

“In every project, or everything you do in life—even just inviting people for dinner—you should try not to just invite people you know already.” – Matylda Krzykowski

It’s actually very difficult to summarise all of Feireiss’ and Krzykowski’s practices in one word or job title. This is due to the importance they place on their work being transdisciplinary. “I don’t believe in any monodirectional approaches. If we want to understand our complex reality and accomodate the needs of today, it makes much more sense to work with a broad range of people,” says Fereiss, highlighting how for him, teamwork and collaboration are key facets of a transdisciplinary practice. “Transdisciplinarity doesn’t mean I can do everything myself. It rather means for me that I can draw analogies and transfer approaches between contexts and perspectives, beyond the borders of one’s own discipline and do that collaboratively and in a team.“

Krzykowski argues that, while transdisciplinarity has always been present in creative spheres, certain systemic factors have prevented it from thriving. In the media and in the context of cultural journalism, for example, we still rather “portray singular successful icons instead of collaborative, transdisciplinary projects. Funding structures are also an issue. “Even in the arts, when you want to apply for a grant, you have to specify whether you’re working in art, architecture, or design. The latter is usually not funded and remains in the commercial realm, despite its cultural potential ,” Krzykowski explains. “The system needs to catch up and establish support systems in which one doesn’t work in such singular ways.”

Educational systems are also culprits of discouraging individuals to cultivate talents in more than one area. With this in mind, Feireiss, who is currently visiting professor for transdisciplinary artistic education at the Berlin University of the Arts, has been piloting educational formats that transcend disciplinary boundaries and forge relations between a wide range of studies in an open and transparent critical dialogue. “It’s important to challenge fixed binaries that stabilize meaning and representation“ says Feireiss. “I like to keep meaning open-ended and in a perpetual state of becoming.”

Krzykowski adds that schools often pressure young people to decide on a career at a young age, and then to stick to it for the rest of their lives. “I’m in my late thirties, I’m still not precisely sure if I will stay on the road I’m on. I think it’s a very Western European belief that you cannot shift within your framework. People can’t handle the idea that you might be educated in a certain field and then turn 360 degrees and try something completely different.”

In order to further challenge pre-existing structures, Fereiss and Krzykowski have been working together on a new, holistic summer school or “educational format” called Methods of Operation. “We’re planning to bring together various practitioners from very different fields to elaborate on their respective methodologies,” says Feireiss. “They won’t speak about specific projects, but rather their approaches to things and how these can be applied to different fields or situations. How does a lawyer build a case, for example? How does a doctor make a diagnosis? How does a conceptual artist start a project? How does a shaman first look at the subject in front of him?” Scheduled to launch in the near future, the beta version of MOO will likely take place in locations across Berlin rather than in one fixed classroom. “We would like our participants to encounter the practitioners in their respective studios or homes,” adds Krzykowski.

But this isn’t Feireiss and Krzykowski’s first foray into education: the pair have both taught extensively throughout their careers. Aside the Berlin University of the Arts, Feireiss has been teaching and lecturing at various universities worldwide including Harvard University and the Massachussets Institute of Technology. At the Sandberg Institut in Amsterdam he developed and directed the temporary Master of Fine Arts and the Design program Radical Cut-Up, which examined cut-up and collage as a contemporary mode of creativity and dominant model of contemporary cultural production worldwide. Krzykowski has been a visiting professor in the Industrial / Interface Design department of the Muthesius University of Fine Arts and Design, and in 2018/2019 joined the faculty of The School of Arts Institute Chicago in the Department of Architecture, Interior Architecture, and Designed Objects. She teaches courses at HKB Bern and Design Academy Eindhoven and is the artistic lead of CIVIC, a new social infrastructure and exhibition space at the Academy of Art and Design in Basel.

For Feireiss, teaching is not only a way supporting others in their creative, intellectual, and personal development, it also helps him continue to develop himself. “I always say that the moment I really started learning was not as a student, but when I became a professor at a university,” he says. But while he sees himself as learning alongside his students, he also acknowledges that the hierarchy isn’t completely flat: as a course leader he has a specific set of responsibilities. “I’m an educator, and I’m paid for it. I’m a couple of steps ahead in the game and I have to take care of this group of participants. Nonetheless I try to approach the role as less of an authoritative figure, and as more of a coach of a team. We all have a common goal, and I’m in a position to help people to become even better players than they already are for the sake of the team,” Feireiss adds. “I really do believe that my calling is to bring people together. Whatever form that takes, I hope I will continue to do this in the future.” On a playful note, Krzykowski muses that in the future she might like to try out playground design, reflecting her earlier assertion that we should not feel limited to stick in one career for our entire lives. “I’m really not kidding. If someone wants to give me the chance to design a playground, call me.”

Lukas Feireiss and Matylda Krzkowski are transdisciplinary artists and curators. Based in Berlin, Feireiss’ eponymous studio “provides overall conceptual development, design and implementation for diverse formats of knowledge dissemination and visual communication,” while Krzykowski—who is based between Berlin and Basel—works across the fields of design, architecture, art, and performance. Among other collaborative projects, notably co-founded Depot Basel, a place for contemporary design which ran until 2018. She is also the co-founder of curatorial initiative Foreign Legion, which Friends of Friends interviewed her about back in 2018. The pair have also both taught extensively throughout their careers and Feireiss currently serves as a visiting professor for transdisciplinary artistic education at the Berlin University of the Arts.

This story is the first episode of Insights, Friends of Friends’ new content series bringing together leading visionaries to discuss their opinions and perspectives on the industries they work in.

Text: FF Team

Photography: Aimee Shirley