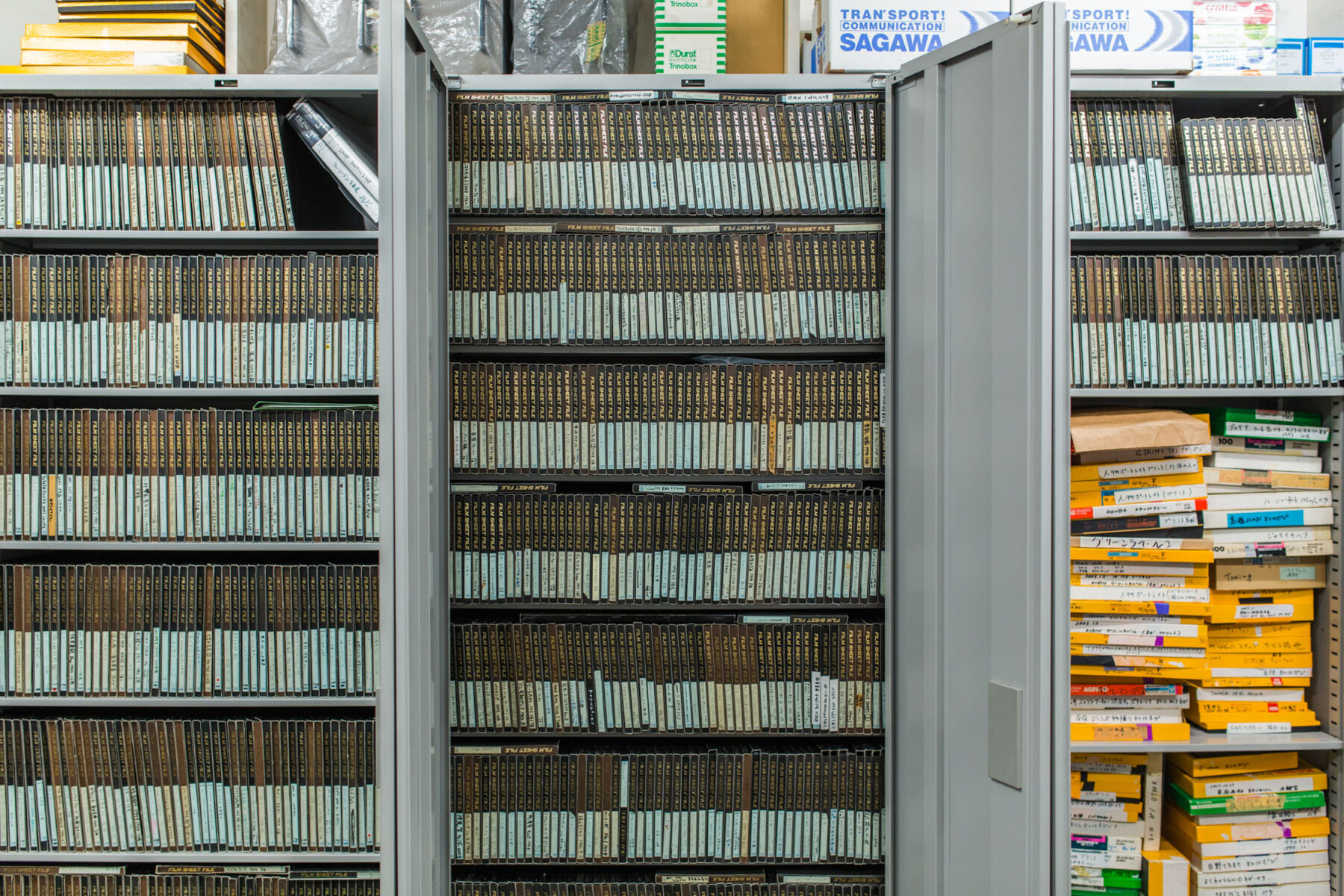

We divide the world into grids in order to better orient ourselves in it, to be able to better represent and search through it. We divide our homes in part using shelving units. We do this first and foremost for practical reasons.

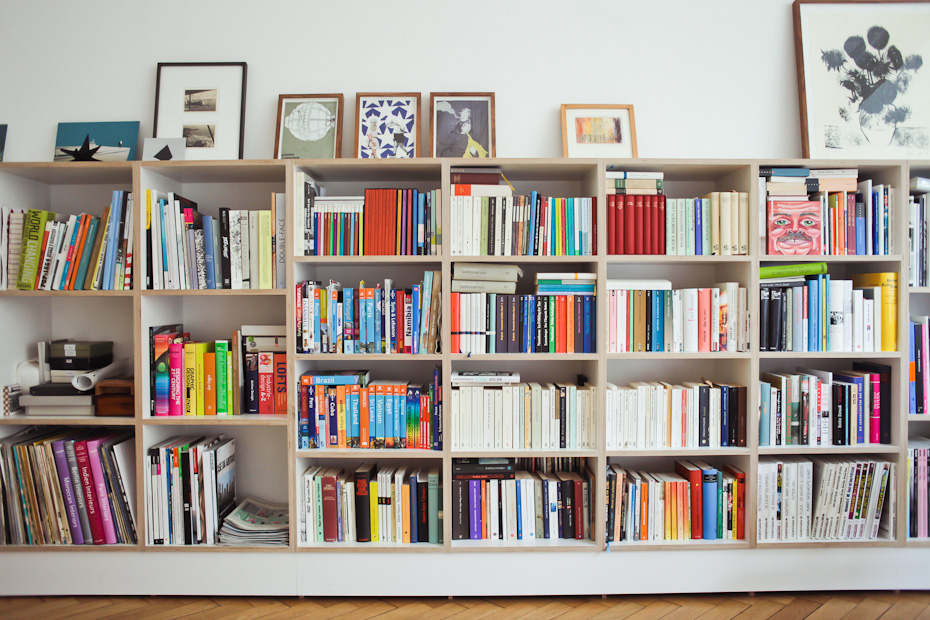

But in addition to books arranged in tight rows, record players, stacked dishes, and lots of potential as room partitions, shelving units hold personal histories. Like the frames of a film, their compartments tell of lives. And like many a picture, some shelves imprint themselves on an entire life.

In my mother’s bookshelves, Günther Grass’s Hundejahre (Dog Years) stood next to Der Butt (The Flounder) and Die Blechtrommel (The Tin Drum), to the left of them Hanif Kureishi’s The Buddha of Suburbia and The Best of Kishon. They were all white hardcover books with black, occasionally also red lettering. The shelf above was filled with an almost perfect color gradient of titles from the Suhrkamp series of paperbacks, and the uppermost—and for me as a child hardly visible—shelf, with a block of bright yellow Reclam books. It was the nineteen-eighties and Benetton had just launched the first United Colors campaign, Greenpeace rainbow stickers were omnipresent.

“We define ourselves through the things we possess, and our shelves are where they are displayed.”

Books (except perhaps for the self-help ones, travel guides, and the aforementioned Reclam and Suhrkamp series) were, however, generally not all that colorful. If they had been, our shelves would surely have looked like a huge box of Stabilo colored pencils, since my mother would have sorted them only roughly according to author, publishing house, and size, but primarily according to color. She herself wore bright pink Oilily sweaters combined with orange carrot jeans at the time, but when it came to shelves, she would place J. B. Metzler’s gray Deutsche Literaturgeschichte (History of German Literature) next to Stewart Homes’s gray Assault On Culture; that is to say that she placed more importance on harmony than on user-friendly organization.

Books whose spines were inconsistent in color, had gradients, or simply no relatives of a similar color, meaning they eluded categorization, found their way to the second row. The shelves were deep enough for pocket books to even be arranged in three rows. Spines that she deemed badly designed disappeared into the closed modules, in which my mother also stowed everything else that seemed too private or somehow embarrassing to her (chaos, pill boxes, and, later, CDs from Die Prinzen—a German pop band). She understood her shelving unit as a type of personal means of expression. Shortly before she bought it, Pierre Bourdieu described taste as a symbolic asset to society.

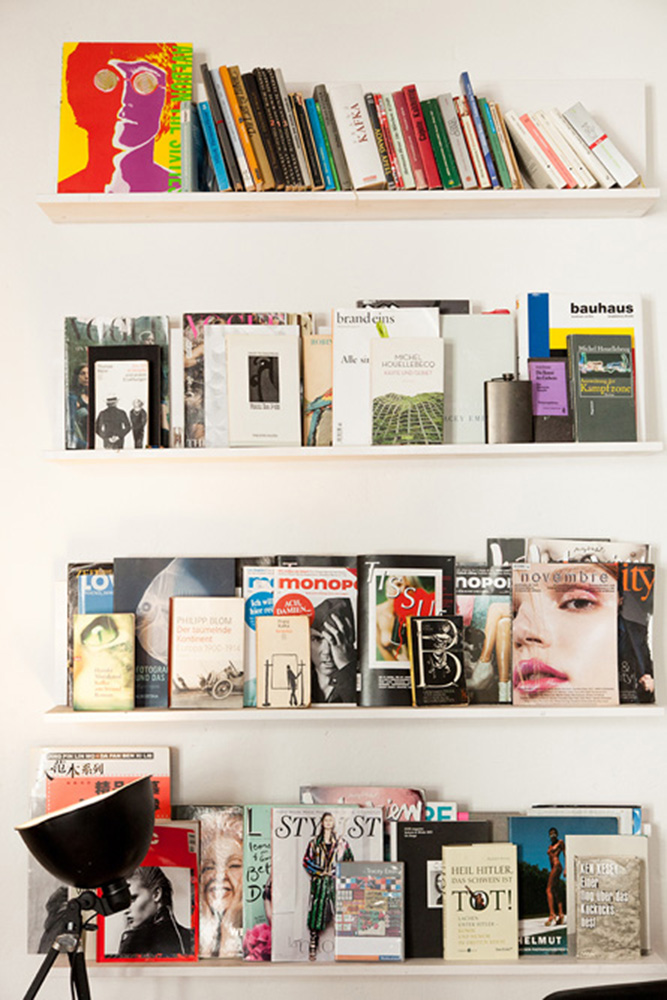

We define ourselves through the things we possess, and our shelves are where they are displayed. “Sharing your shelf is sharing yourself,” explained Peter Knox in the British Guardian; Knox established the Internet page ShareYourShelf.tumblr.com, on which people post pictures of their bookshelves and comment on them. Today, “express yourself” also means: “Exhibit yourself.” It is possible to see shelves not only as a statement, but also as a type case of ourselves. In place of seashells, Matchbox cars, or souvenirs, most of the shelves I know hold fashion magazines and monstrous monographs, records, and a couple of picture frames. My own too: an ailing cactus, a Beatles Illustrated Lyrics Puzzle in a Puzzle, a bird-shaped incense stick holder in ceramic with a Delft pattern, and a fraction of my mother’s library (meanwhile barely still sorted by color).

“Shelves propagate the DIY paradigm of punk.”

A large portion of the “stuff” in our shelving units may be relatively disjointed, but the structure of the piece of furniture makes it into a community. Into a temporary one, since the state of a shelving unit is moody; its open form invites restlessness, constant moving back and forth. A shelving unit is never finished, but is instead always a concept in its very becoming and such it resembles ourselves. Shelving units grow, and sometimes also run riot. As simple and skeleton-like as they actually are, just as much do they scream for interpretation. Intuition. And improvisation. Since things drift—in the most literal sense of Guy Louis Debord’s “dérive”—through the room often seemingly by chance.

Shelving units are universal (since nearly everyone has one) and individual (insofar as no one configures them the same way as someone else). It is possible to buy the most design-oriented shelving units—but, basically, people design them themselves. Seen this way, shelves propagate the DIY paradigm of punk. Seen another, they act as a manifesto of Minimalism, of the Mondrian among pieces of furniture, or even more minimal. Some shelving units are simple grids based on stringent structures. But the best break them. Grids represent rigidity. But, as soon as a system becomes too rigid, one has to liberated oneself from it—this is the essence of every revolution. And of every good shelving unit. Without the celebrated rupture, systems of order are dull, dogmatic, nugatory. They develop their aesthetic potential—and personality—as a result of flexible forms and the dynamic that generates the dialectic pair of order and disorder.

“It isn’t that the things we possess live in us, but rather that we live in the things we possess.”

In “Regal,” the German word for shelving unit, hides the little word “egal,” which means: “It doesn’t matter,” but basically every object in a shelving unit is there for some reason. Some objects have long since ceased being merely things and become symbols for places we once were, for people we once knew. Some remind us of who we actually are or want to become ourselves. While the present in the form of objects likes to float around on sideboards and desks, our shelves tell of the past and the future at the same time. And there are moments in life that such stories seem to us to be as cumbersome as the piece of furniture itself.

When I went to study in London, I left my large shelving unit in storage. Three years later, the box with all the old contents of the shelves seemed to me like one of Warhol’s time capsules, and cleaning out the shelves in Berlin like an introduction to the next chapter of life.

With reference to his home library, Walter Benjamin once appropriately wrote that it isn’t that the things we possess live in us, but rather that we live in the things we possess. My mother said if our house were on fire, then—apart from me and the cat—the books on the shelves would be the first things that she would rescue. Fortunately, our house never caught fire. But things certainly have fates.

“Shelving units grow, and sometimes also run riot.”

When my parents got divorced at the beginning of the nineteen-nineties, one single module of the white shelving unit stood in the bathroom in my father’s one-room apartment, and looked as lost there as he did between the unfamiliar mothers when he picked me up from school on Fridays. In the module was barely anything more than his toiletries bag and a bottle of Wash & Go. Symbols of passing through. He did not plan to stay there for long. The other eleven modules of the bookshelves remained in the living room of my mother, who had, however, sorted her books anew. A small block of brightly colored self-help books now separated Grass’s Blechtrommel and Kureishi’s Buddha of Suburbia. It was the end of one era—and more or less the beginning of the digital. Soon people would sort more data than things.

The overflowing “temp” folder on my computer’s desktop may be some sort of digital equivalent to the drawer modules of my mother’s shelving unit, but no “research” folder can replace long rows of books and in most places analogue collection points for things remain. However, I have been in homes where there is no shelving unit at all anymore. Some people now only still mount narrow prestige-object presentation boards on their walls, a couple of screen prints, and their bicycle. This can be called Minimalism. Hip. Or a new nomadism. The apartments of the post-shelving-unit generation speak of very great freedom. But they lack histories.

This essay was originally published in the Personalities book, a collaboration between USM and FvF.

Anna Sinofzik studied graphic design and design critique in London. She lives and works in Berlin as a freelance culture editor and author.

It would be hard to throw a rock around FvF without hitting a shelf, but to start, you might want to check out some of our USM portraits.