Matthias Last and Antonia Siegmund’s reciprocal nature is unveiled through a series of common denominators and the way their ideas converge.

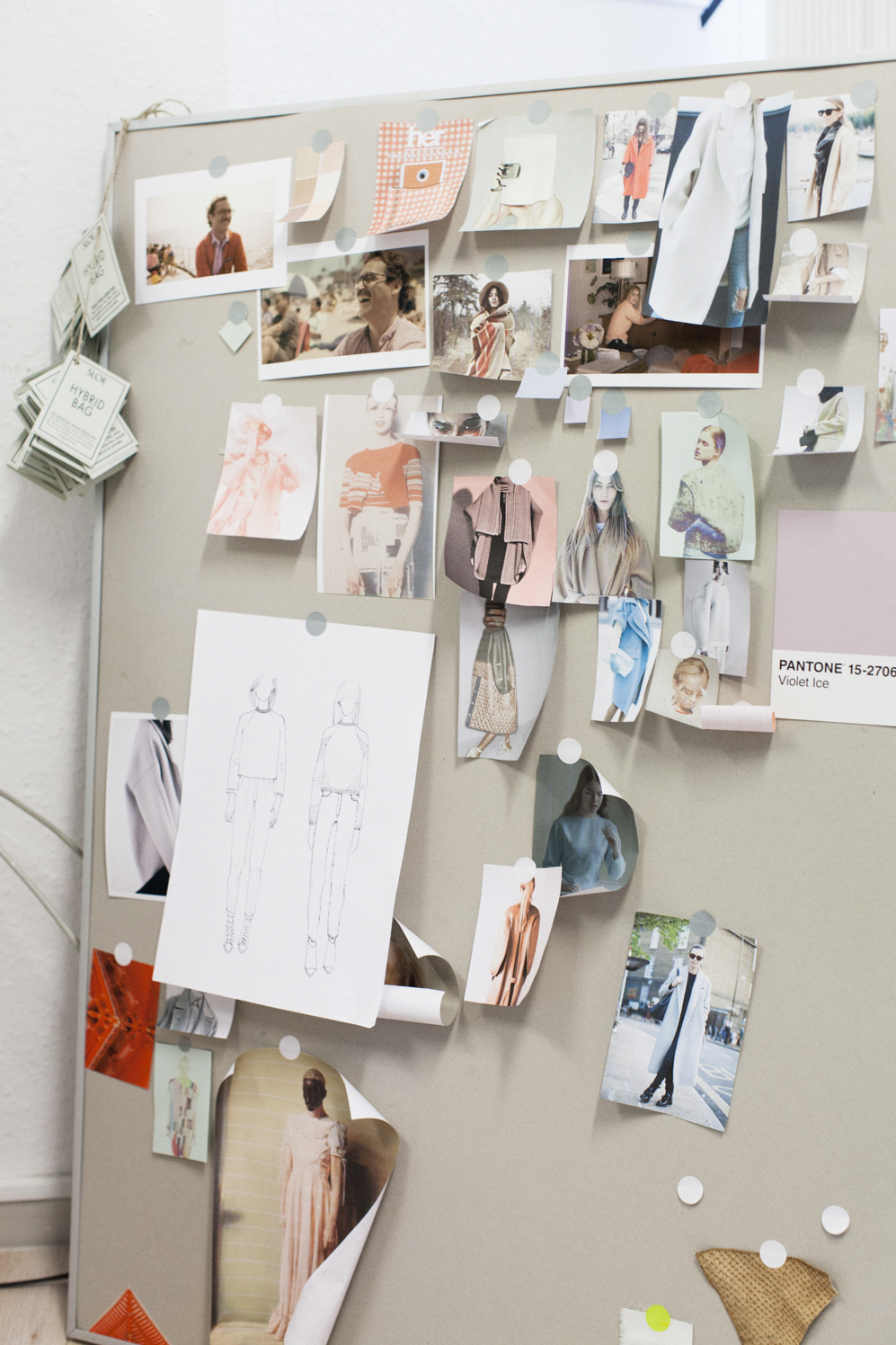

Antonia, a Central Saint Martin’s graduate, and Matthias, founder of design bureau Studio Last, started their elegant, understated and deceptively simple fashion and accessories label, SLOE, three years ago. They single-handedly revived the bucket bag and countless staple pieces to boot. Highly conceptual and fluid in its design, SLOE, like the creative team’s strange but streamlined Berlin-Kreuzberg apartment, is the result of that rare little thing that happens when two people, creative in their own right, connect to birth something new.

Surrounded by ceramics, accompanied by 90-year-old framed butterflies, we sat down in Antonia and Matthias’ kitchen to discuss creative cross-pollination, the aesthetics of New Wave music and the life and death of fashion.

This portrait is part of our ongoing collaboration with ZEIT Online who present a special curation of our pictures on ZEIT Magazin Online.

-

The layout of your apartment is atypical for Berlin. What’s the story behind it?

Antonia: The apartment is definitely from the turn-of-the-century Art Nouveau era but is very distinct from classical architecture. For example, all windows are completely different. Usually, they are all the same – maybe one will have a bay window, maybe not. Here, some windows are rounded off or some are shaped like fans.

Matthias: Yes, the apartment is pretty special. They apparently call this layout a ‘General’s Apartment,’ because you can walk from room to room through the entire flat. Usually these service entrances, with those dark, boat-like metal stairs, are found in Parisian apartments.

-

Your interior is also different from the usual clean and minimalist Berlin apartment. How did that develop?

Antonia: I became very passionate about interior design. Maybe I’m a little obsessive-compulsive about it – I always have to create something. I’m creating all the time for work and of course I won’t lose my passion for it, but it’s still a job. Furnishing turned into an outlet that could offer a different kind of release. I’m a total perfectionist and, in combination with Matthias, breaks occur that are interesting but still coherent.

We were very conscious of what kind of atmosphere we wanted to create. That huge sofa that looks like a giant boat in our living room, for example, we built ourselves. It’s pretty dominant and we actually wanted it to feel solitary in the room. The space should feel free, but still warm. We can’t live in overly clean spaces.

“This music and its aesthetic holds immense emotional value for me. It’s almost like coming home.”

-

Does your taste differ sometimes?

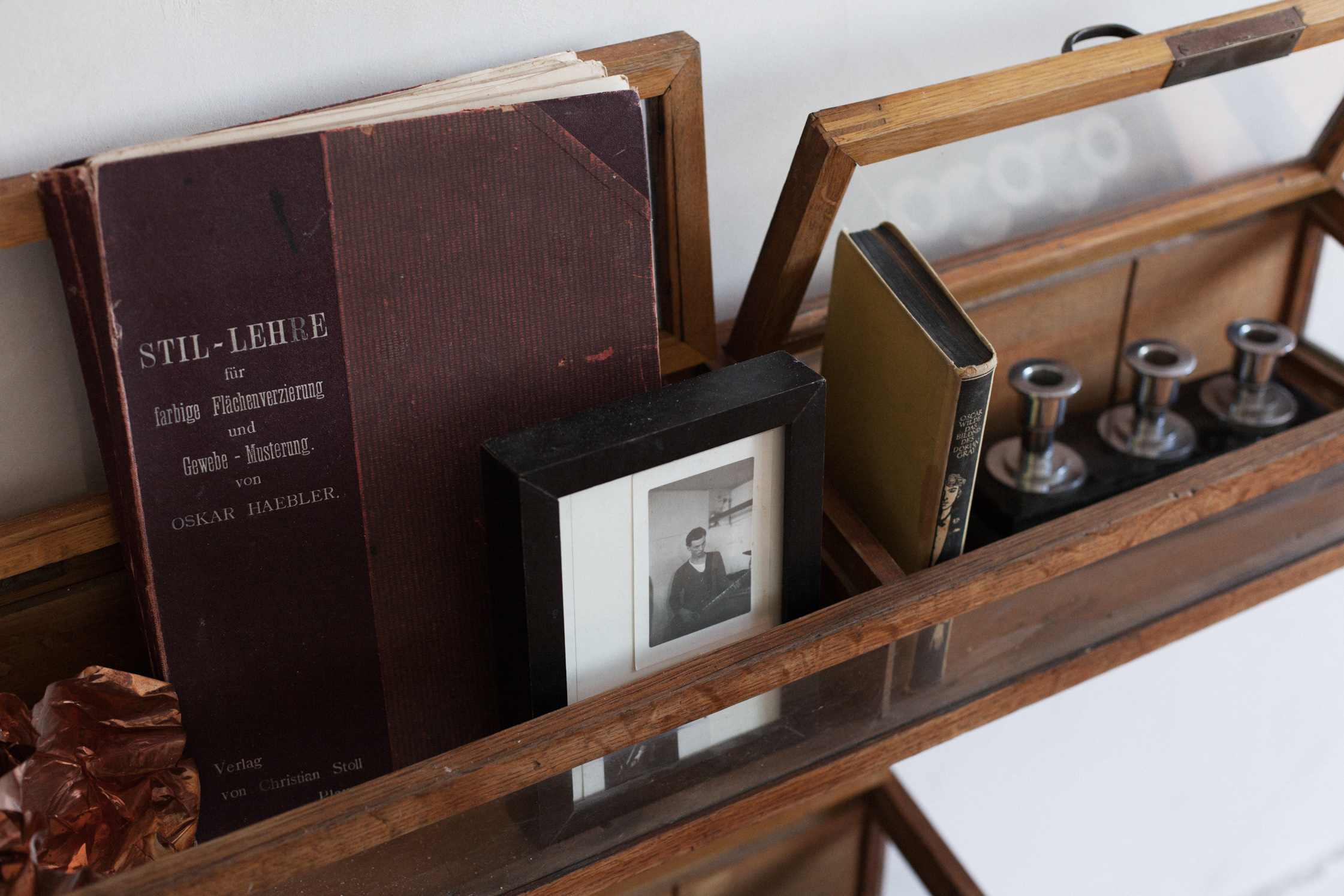

Matthias: Antonia is more opulent when it comes to furnishing; I’m a little cleaner. That’s how we create balance. The space is alive because there isn’t much in it. But I too have a few things that are close to my heart. Werner Amann’s picture in the bedroom, for example. I collaborated as art director on his book. The image is very expressive and I was very happy that it became his book cover. A lot of things in our home have a very personal history for us. This is the case for Nir Rackotch’s self-portrait over the sofa, for Axl Jansen’s photography in the hallway, for the poster from Jonathan Meese and the wood collages from Katharina Trudzinski.

-

What’s most important to you in this apartment Antonia?

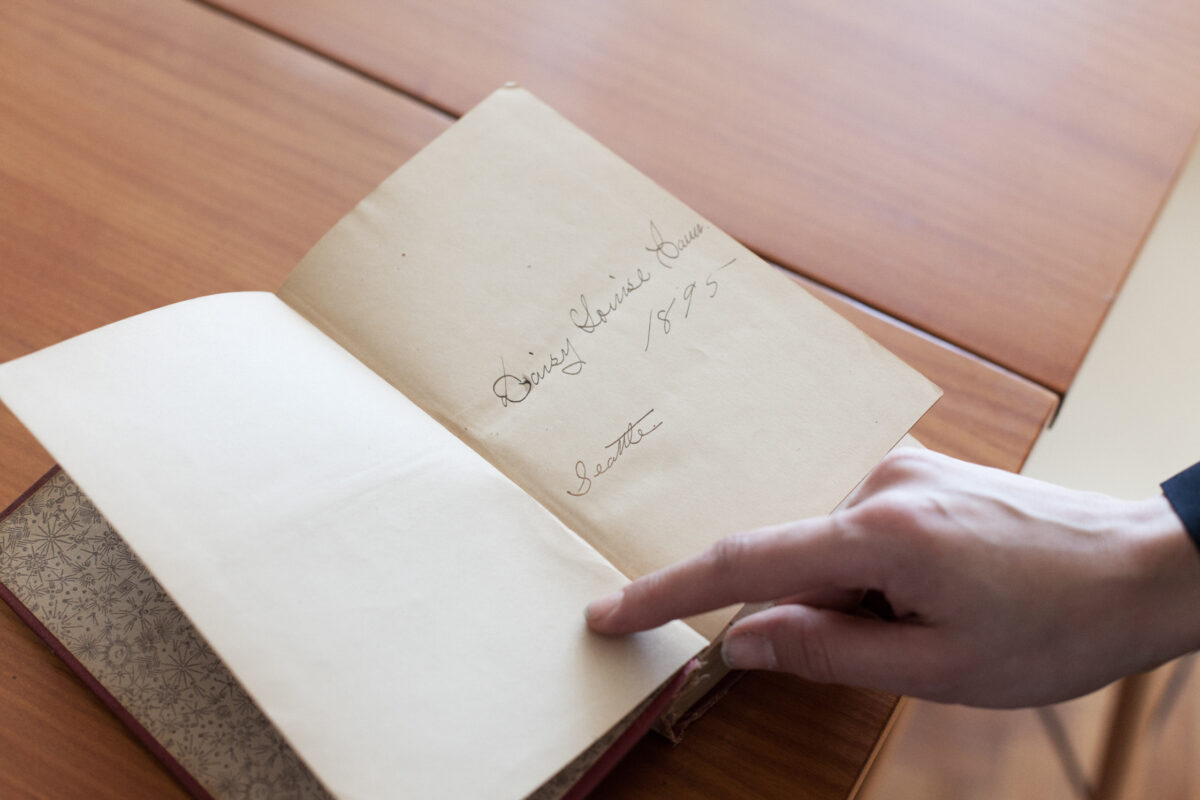

Antonia: My butterfly collection means so much to me. I’ve been moving them from apartment to apartment for ten years now. My great-grandmother gave them to me and, even though she passed away such a long time ago, she is still incredibly important to me. Her whole living room was covered in these butterflies, from the top of her sofa to the ceiling. A friend of hers, some time in the 20s, was a zoologist and traveled all over for these. He sent her a butterfly from everywhere in the world.

-

What’s the difference between the creative conception of a living space and that of SLOE or Studio Last?

Antonia: I do think there are parallels. At least in the way the process grows. There’s a concept, but it never stagnates. But SLOE does happen in a pretty rigid structure. The label has an identity and it stands for something specific – an ease, but also strictness and straightforwardness. Also, with good materials you realize that you don’t need much to create something amazing. If you want something simple, understated and demure, yet still interesting and special, then materials are just very important.

Matthias: Essentially, there’s no big difference. But I also lead a lot of commercial projects with Studio Last, so SLOE, or the creation of a living space, is a lot freer and more “me.”

-

Does the market influence SLOE’s designs?

Antonia: It’s not easy to create with an audience in mind. There are always moments when I think, People will like this. But I try not to be influenced by that. Once you start, the label will lose its identity. It begins with a small detail and at some point it’s all frayed around the edges. It’s important to listen to yourself, to keep your eyes open and play with it. If we wanted to produce for the market, we’d be doing something else.

“I became very passionate about interior design. Maybe I’m a little obsessive-compulsive about it, but I always have to create something.

-

You founded SLOE together. How do you divide the work?

Matthias: It’s a symbiosis, there’s no real division. At the end of the day, Antonia is the fashion designer. She knows all about materials and fashion; SLOE is her main focus.

Antonia: Without getting too concrete about it or sitting down to do drawings together, our products are always the result of how we communicate – our exchanges. Finding ideas is a joint process. The production of each item is my part, but finishing a product isn’t enough. That’s when Matthias jumps back in. We develop the product’s presentation as a whole.

-

Such creative symbiosis is hard to find. What defines it?

Antonia: Well, I studied fashion design, first in Hamburg then at Central Saint Martins in London. After graduation, I wasn’t sure if I even wanted to stay in the fashion industry. I felt like my studies had influenced me too much. Even more so because I knew who I was, what I wanted to do, and what my style was even before I went into the degree. Throughout my studies they just kept telling me: “But you can’t be finished yet!” And of course, it’s good to push people beyond their limits. But, apart from these valuable aspects, I partially felt that by providing a broad spectrum I would lose my personal style. It didn’t help, but sometimes removed me from who I am and what I like. In the end I did all sorts of things and totally lost myself in the process. Then I came to Berlin and met Matthias. We had such an amazing exchange going and had a passion for finding new, exciting things and sharing them with one another. That was good for me. On the one hand, he introduced me to new things. On the other hand, it felt like I was finding my own design style again. I think, in the end, this common denominator is what created SLOE.

-

What exactly is this common denominator, then?

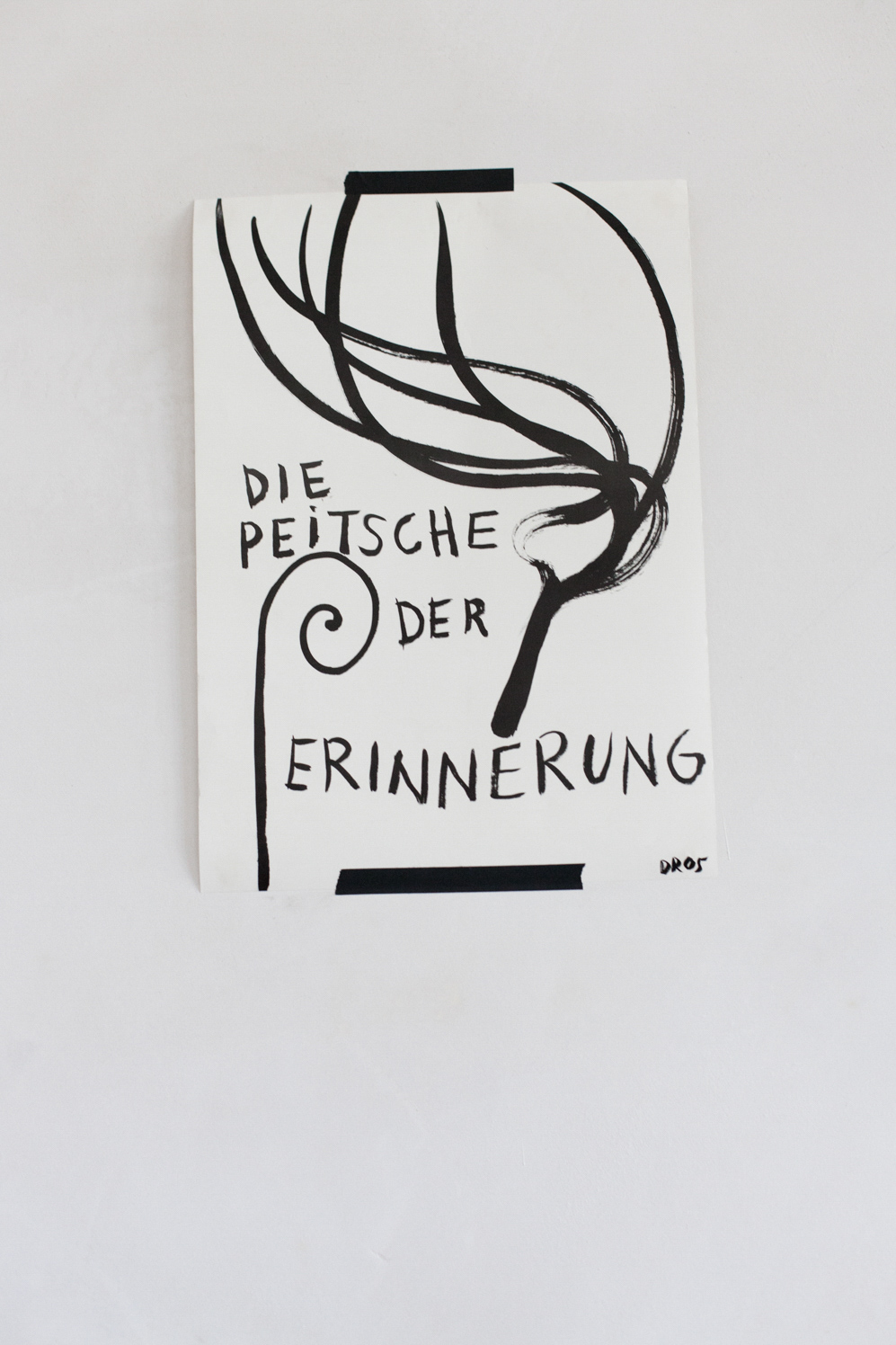

Matthias: Our taste in music, for example. Dark, edgy and angular. We’re both heavily influenced by New Wave and Punk music. Our campaigns express this love.

-

How did you develop this aesthetic?

Matthias: I had a pretty simple upbringing as a half-Norwegian in a GDR Plattenbau, where everything was pretty uniform.

I think my taste was shaped by curiosity. I was always in transition, maybe because of insecurities, but who knows. I always wanted something new. Inspiration and change are automatisms for me. I think both of us had to find a way to set ourselves apart. For me at least, it was through music and the aesthetic it carried. Bands like Psychic TV, Throbbing Gristle, Joy Division, but also Sonic Youth and corresponding designs like those of Raymond Pettibon.

Antonia: My story is pretty similar, even though my parents played a huge part. We didn’t listen to kids’ music. We had Nick Cave and Palais Schaumburg. I resisted that for a while. When I was 13, I wanted to be totally bourgeois. That was my rebellion. I still carry this dichotomy, in a good way. It’s about reconciling contradictions. Curiosity keeps you from latching on to the next best thing. You’re constantly searching for something that touches you.

I’m very close to my parents. When my dad was in a good mood on Sunday mornings, he’d put on Sunday Morning by Velvet Underground. He still does that sometimes. That music and aesthetic is very touching to me.

-

Does it bother you that the fashion industry cites sub and youth cultures, ultimately diluting the cultural message their aesthetic used to convey?

Matthias: I do think it’s a pity that there are very few clearly defined subcultures around nowadays. Clothes don’t take a stand anymore. But I think the reason for this is pretty obvious. You could argue that the fashion industry and advertising have been exploiting subcultures, draining them of any real meaning. But we can’t blame the fashion industry for this. That’d be too simple.

The origin of this dilution is partly due to an increase in tolerance, which, in itself, is a good thing. But applying the freedom of “anything goes” to all matters of taste has destroyed extremes. They’re just not effective anymore.

Antonia: Previous generations have fought for this kind of freedom. And I’m not just talking about the freedom to wear whatever you want. Back then, fashion, music, and politics were intertwined and influenced one another. Fashion was a political statement. The reason that nobody is taking a stance with fashion anymore is that we’re less political. The globalized world has become a lot more complex. Nowadays, we’ve become too comfortable, and current social and global problems don’t affect us enough to take a stance.

-

In a recent interview, Li Edelkoort declared that fashion is dead. What’s your take on that?

Antonia: People criticize a lack of innovation in fashion all the time. That annoys me. Not because I feel attacked, but because the statement is narrow-minded. Of course, nobody is going to reinvent the wheel. We’ve seen all sorts of silhouettes, everything’s been done before: on the catwalk, in subcultures or folklore. But that’s not new. Dior’s “New Look,” which was hailed as a totally new silhouette, is basically a short version of a Biedermeier dress, for example.

We can thank the high street market for our uniformed look and the fact that you can find exactly the same stores in every large city in nearly every country. We fill our closets with stuff and think our individuality is measured by the quality of our combination abilities. But either way, individuality is not a consumer product, and if you want your clothes to stand out you either have to go make something on your own or invest in smaller labels.

Matthias: The differences in fashion have become very subtle. You really have to take a close look nowadays. Details, combinations of materials and colors are what matter. But I think it’s good to really examine the intricacies of a product.

Learn more about the fashion label SLOE and Studio Last.

Photography: Mirjam Wählen

Interview: Jennifer-Naomi Hofmann