How many ways can intimacy and desire be expressed? What role do they play in the creative sphere?

In media as well as other creative realms they often appear as mutually exclusive, or at least very closely intertwined. As newer perspectives are brought to the forefront of what is considered mainstream media, however, newer generations delve into ideas of intimacy and desire with fresh eyes and unconventional approaches.

The inclination of creatives to probe these themes through their work spans generations, cultures, and disciplines. Greek god of sexual desire Eros enjoys a steadfast, prominent role in many artworks and mythological tales, usually as a roguish child or a handsome youth. Songs of love and longing have been a mainstay for composers and musicians since ancient times, from the anonymous Greensleeves of the Renaissance era to Nina Simone’s My Baby Just Cares for Me to Leonard Cohen’s I’m Your Man. Depictions of innermost thoughts and desires in art, television, and theater have had a wide range for centuries, from Shakespearean soliloquies to Fleabag’s expert manipulation of her audience through breaking the fourth wall. But it would be disingenuous to suggest that certain representations of intimacy and desire haven’t prevailed: these have often embodied heteronormative, sexualized perspectives that denigrate those who stray from the perceived norm as taboo.

Today, this widespread narrative is shifting. Through the rise of the internet, trailblazing creatives, and their amplified voices, we are seeing the representation of intimacy and desire becoming more diverse, nuanced, and thoughtful. The connection between intimacy, desire, and shame are being reconsidered, challenged, and in some cases detached entirely. Our concept of what intimacy and desire look like, and how they ought to be, is being broadened by the day.

As such, we sought to gauge the scope and ever-evolving nature of intimacy and desire through the eyes of three creatives. With the insights of Atusa Jafari, Adam Munnings, and Jade O’Belle, we explore the role it plays in their practice, the importance of representation, and the potential for authenticity and self-expression through these themes.

Atusa Jafari on how art can be a vessel for intimacy

For Iranian-born, Darmstadt-raised, and now Berlin-based oil painter Atusa Jafari, “anything can be intimate.”

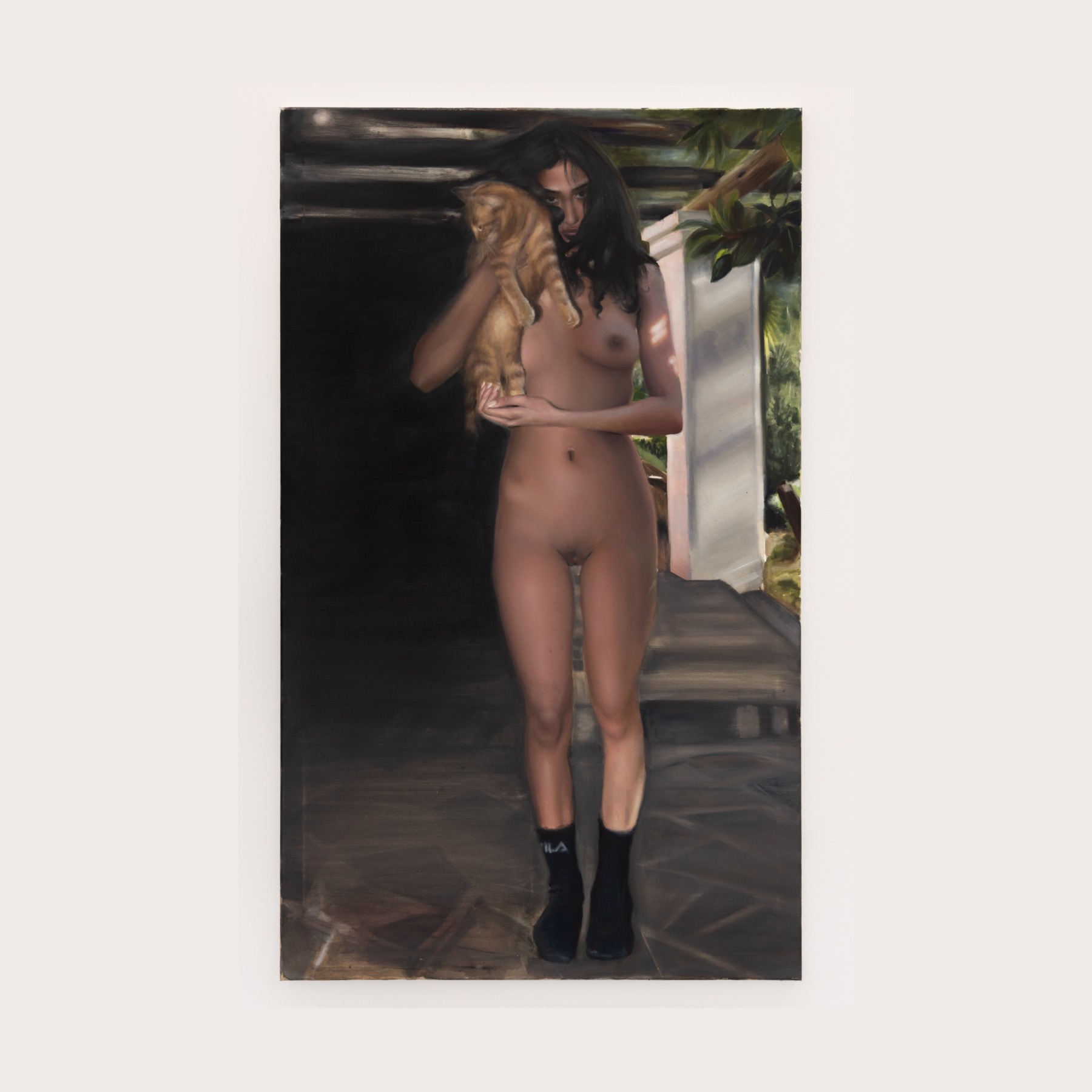

Portrayals of nude or half-dressed female figures are no new concept for the art world, but Atusa approaches nudity from an angle less orthodox. Atusa’s paintings are depictions of feminine bodies positioned intimately–but markedly captured without the typical heteronormative lens of gratuity. Her subjects squat within nature, half-clothed, chin in hands, face turned towards the viewer, or they recline on bedsheets, eyes downturned, clad in underwear and Ugg boots, sanguine. In her piece ‘Hiding but Not’, we don’t see the figure’s face. She is on the floor, displaced locks of blonde hair covering her features. One hand is curled between her legs, the other gripping the arch of her foot. ‘My Moon and Sun’ is a disconcertingly realistic painting featuring a woman standing face-on, utterly naked bar the pair of FILA socks she sports on her feet. She holds a stripy ginger cat aloft, and her visage is unapologetic, unwavering, knowing.

“My paintings are not about making demands,” Atusa says, on how the representation of intimacy and desire in creative practices is changing. And certainly, even as a “spectator” to her subjects, her gaze is decidedly undemanding. The figures in her paintings often emanate a sense of pure ease, unperturbed by their audience. Instead of tense poses vying for superficial eroticism, they appear to place themselves at their leisure. They are uncompromised.

Atusa does not operate solely as a spectator. In her own practice, she has evolved in how she depicts intimacy, by moving towards depicting, alongside her subjects, herself. In part, she has turned inwards, touting her self-examination and her growing ability in sharing self-portraits as an expression of intimacy, and how art can be a vessel for intimate connections between strangers. “The things I experience with myself, opening up to myself and really trying to understand myself, I’ve never considered something intimate, but exhibiting them and suddenly having a viewer makes them intimate,” she explains. “Standing in my studio were a few self-portraits I painted without thinking they would ever be shown […] We share intimate moments with people we trust, but art is different, we also share [it] with people we don’t know.”

“Exposing what we see as the dark sides of our personality, the parts that we deny most of the time because they complicate the image we project of ourselves, that is intimacy.”

Forthcoming about her fear in showing herself through her art, Atusa also notes this anxiety as a unique element to her creativity and practice. “…It makes me vulnerable. I show myself and the things I’m most afraid of.” Intimacy itself, alongside vulnerability, can be nebulous concepts, their meanings and conceptions varying and perhaps even contradictory to many, but Atusa separates intimacy from the sheer act of presenting to the world, and highlights it as an internal process: “Even though I think of it as being afraid to share the intimate parts of my body, the fear itself is actually much more intimate. Why am I afraid to show it? Exposing what we see as the dark sides of our personality, the parts that we deny most of the time because they complicate the image we project of ourselves, that is intimacy.”

And what of the future of artists and how their creative processes and output intersects with intimacy and desire? As a member of Generation Z, Atusa was born into the role of social media expertise, with the presence of Snapchat geofilters, Instagram stories, and Twitter hashtags ever-present and pervasive: “Much of today’s world is staged and seems intimate but is actually constructed.” The permeation of social media into the art world greatly affects its future, and Atusa uses it to illustrate her predictions–from both an optimistic and pessimistic perspective.

“When I look optimistically into the future, I see that we prioritize our self-expression [.. ] as something intimate and wonderful and get to know each other better, so that we can indulge our authentic selves with a healthy collective consciousness. Pessimistic: that this is becoming less and less important, a kind of semblance of individualism is emerging, reality TV is considered an intimate insight, paparazzi photos are an honest snapshot.

But I’m more positive.”

Adam Munnings on celebrating and creating inclusive intimacy

Tasmanian-born, Berlin-based film director Adam Munnings’ works portrays intimacy and desire in a way that is both “unapologetic and celebratory.”

His visual aesthetic is ambitious and spontaneous; through bursts of color, flashes of whimsy, and cinematic flair, he constructs a world unique to each project. But Adam isn’t an example of style over substance. The aesthetic of his work is emboldened by the intense undercurrent of love for his community, of engagement with his surroundings. “I love to engage and partake with what excites me,” he says of his creative practice. “The queer community, radical self-expression, nightlife, dance, romance, adventure […] sometimes it’s beautiful and harmonious, at other times it’s intense and chaotic.”

Even in his more commercial work, Adam merges his vibrant aesthetic with earnest appreciation and compassion for his community. In ‘Zalando Pride’, it’s apparent that Adam’s connection with his subjects elevates what appears on camera. In this particular piece, we begin under a canopy fanned over a stretch of brilliant blue sky. The camera moves deftly, following a young person who races downstairs from a balcony overlooking a garden. Neon pink trainers fly through the grass. The voice-over talks about self-expression, whilst the attendants of Pride are captured in the sunshine, buoyant and unabashed. Poses are struck. Fashion is flaunted. The video is both dynamic and empathetic. The voice-over calls self-expression “absence from shame.” And Adam’s gaze reflects this: pride is abundant, happiness oozes from the screen, inhibitions are cast asunder.

Adam grew up in a small town in Tasmania, and he notes the distinct lack of gay role models he had access to during his youth. “To desire another man was made out to be evil or disgusting.” Certainly, growing access to the internet has made this easier in recent years, but queer desire is only freshly becoming mainstream: “I feel like I’m trying to create visual worlds I never saw as a teenager.” Within the visual arts, particularly photography and film, Adam notes the prominence of depictions of intimacy and desire–the inherent nature of such imagery to provoke human reaction–but draws attention to the problematic lack of representation. “Nowadays it’s so refreshing to see minority groups taking center stage in narratives, and the taboo of homosexuality and race is diluting. Not completely, unfortunately, but it’s on its way.”

The slow shift of who takes to the fore of mainstream narratives of intimacy and desire is represented within Adam’s work. During lockdown, he conceived of Lunchbox Candy alongside music producer Elninodiablo, described by the latter as, “sexy, inclusive, unapologetic, joyful and extravagant!” Inclusive, queer-friendly, and groove-focused, Lunchbox Candy operates as a sequin-studded nucleus for the Berlin’s creative community. Adam’s enthusiastic engagement with the queer, radical, diverse creative community in Berlin is infused in his work, and is partly what makes it so unique: he approaches what he captures on camera with understanding and the drive to forge true connections.

“Intimacy should not be exclusive.”

“I like to create a connected, safe space environment throughout my practices,” he says. “I’m fascinated by the way we navigate intimacy and desire in the current day, especially in the queer community in Berlin, which is ever-evolving. Intimacy goes hand in hand with vulnerability, trust, and surrender. Desire can be a stepping stone into intimacy.”

To Adam, the ultimate revolution in the future will be deconstructing gender binaries. “Intimacy should not be exclusive,” he explains. “It’s not about taking away, it’s about giving more.” Intertwined with deconstructing these binaries and oppressive systemic beliefs is, to Adam, the potential we have to explore intimacy and desire unburdened with shame. “With consent and trust we should be able to engage in an intimacy that serves our hearts and souls fully. How that’s expressed should just be honest. It’s happening and people need to see and understand it’s possible.”

Jade O’Belle on intimacy which is nurturing and supportive

When articulating intimacy and desire in her creative practice, Jade O’Belle tends to begin with a question. She may ask, “How do I relate to people, species, and objects?”—or it may be a question that begins as part of a conversation, or blossoms from a particular feeling.

Intuitive thinking is a critical part of Jade’s work. As a creative director, multidisciplinary artist, model, and performer, she has the unique perspective of a creative who has worked both in front of and behind the camera. She has been described as a muse for fashion designers and photographers, a moniker interlaced with mythology and intrigue. Within her creative practice, she takes a meditative approach of dissecting “notions of identity, queerness, and the body.” The breadth of her creative experience means that she’s not limited to a particular medium: she plays with film, costume, performance, and sound to engage with the topics, often through “mythical visual imagery”.

The trailer for Jade’s short film Birthright (her directorial debut) is a taste of her work. Ethereal music underscores dreamy visuals. Shots of slender candles being lit and the sea rushing the shore are spliced between dancers moving with grace and power beneath a hazy filter. The tone merges a sense of the fantastical with hints of gothic romanticism. Birthright focuses upon “concepts of queer femme identity, rituals, and the body [and] explores my paternal ancestral connection to Yoruba culture”. Through constructing costumes created from ritual objects, Birthright presents “a diasporic portrayal of Yoruba iconography”. The celestial visuals are enriched by Jade’s reflective process, and her openness to using her own rituals and emotions as an anchor for her work: “[I use daily rituals] to create connections to memories that have been passed through my body that inform the methods I use to move through the world.” Birthright is an invitation into an otherworld, in which you can embark on a journey alongside a High Priestess. Produced by Girls in Films, Birthright—as of yet unreleased—is a reclamation of selfhood, an escapist and magical musing on the body and empowerment.

In conversations within the creative realm, Jade, instead of establishing intimacy and desire as distinct, separate themes, speaks of intimacy as a result of desire: “When thinking about intimacy, the desire of emotional, physical, mental, and spirituality is needed to form some type of bond.” This perspective casts intimacy itself as a form of desire; there is a suggestion that intimacy can be approached as the culmination of encompassing desires. It’s a frame of mind that could be seen as divergent from the typical mindset towards intimacy and desire, but it can be a manner of spreading fulfillment and encouraging self-care. “The closeness between people, species and objects, conveys vulnerability that is shameless,” she says. “…this can be a unique way of expressing intimacy that is supportive and nurturing.”

In her work and philosophy, Jade highlights a connection between intimacy and community. Whilst intimacy is often explored in terms of the self, or beneath the lens of romantic or sexual relationships, Jade interrogates the importance it has within communities. “I really want to find a way to express topics and narratives to find community and a sense of belonging where I learn and understand myself and others in a more intimate way.”

The future of how we dissect intimacy and desire through art and creative processes is the prospect of uncovered ground, which future generations will have the capacity to excavate and examine. Prompting such discovery will be the dialogues opened by this generation: “Vulnerability and self-exposure are bled through our daily lives more intensely with the accessibility to each other’s lives and ways of thinking,” she says of the current creative climate. “For future generations, the change will cause the curiosity of finding deeper meaning [in] expressing intimacy.”

Our Deep Dives are a place to explore different themes, issues, or questions from more than one perspective or source. These regular features shed a light on creativity’s relationship with other fields and dimensions of life.

If you would like to read more about the intersection of intimacy, desire, and creativity, you may be interested in Caroline Tompkins’ Photo Essay, ‘An Anxious Romance’.

Text: Ellen McBride

Images courtesy of Atusa Jafari, Peter Kadeen, Adam Munnings, Jade O’Belle, and production company Girls in Films