When Tomás Saraceno speaks about humans and other lifeforms, he refers to them as passengers with planet Earth representing the fastest vehicle that ever existed. It moves at a speed of 108,000 kilometers per hour, and it will still do so even when we’re not here anymore.

Art and science are often described as two opposing disciplines. Looking at the practice of the Argentinian artist and trained architect Tomás Saraceno, such a differentiation is quickly disproved. Climbing atop one of his larger-than-life installations feels like becoming part of a scientific speculation about alternative habitats, letting one sense the often disregarded correlation of the human body and its environment in a new way. From his Cloud Cities projects, to installations such as In Orbit and On Space Time Foam and his experiments around spiderwebs and aerosolar journeys, the common thread in Tomás’ works lies in a life lifted off the ground.

“Everything is in everything.”

-

Let us start with a question about terminology as it’s often not easy to tell whether your works should be described as models, sculptures, experiments or tryouts. How do you tell one thing from another?

Tomás: This question occurs often here in the studio, as it also did earlier in my career. People come to my office, or studio—you see, the terminology is pretty unclear sometimes—like Thomas Bayrle often did when I was still studying under him, and they would say, ‘Oh Tomás, I love that thing, can I have it?’ Just some things from the huge mess in the studio all of a sudden receive that appreciation and I would start seeing everything differently. Or I would recognize some things I would otherwise not have noticed. As a result, I would give this particular aspect more space, in terms of physical presence, but also in my mind. Other ideas, thoughts and convictions would then start to move and rearrange. This is also how a model or an object transforms into an artwork: it occupies a certain space, physically and mentally.

-

Do the forms that your artworks take also have to do with how you went from architecture to fine arts?

I’ve been studying architecture and this is a discipline where you deal a lot with people. I remember Vito Acconci once said to me, “Don’t you come from a discipline that builds sculptures for humans?” What I am doing has never really been architecture, but what has always been at the center of my practise is incorporating the human scale and the relation of human bodies. And I was always more drawn to the experimental side of architecture or practices such as the one of Gordon Matta-Clark.

-

When was it that other species, such as the spider, came into your work?

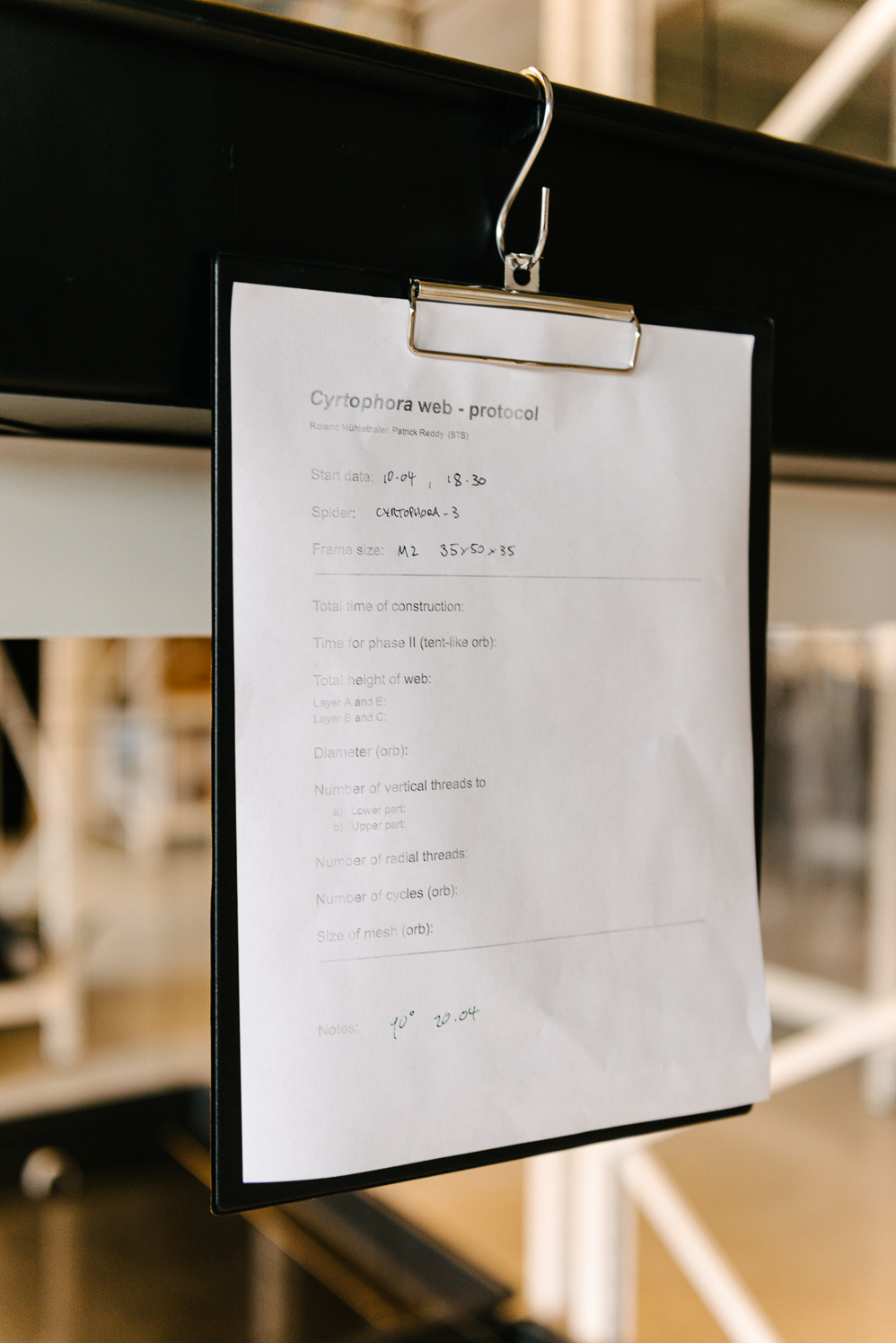

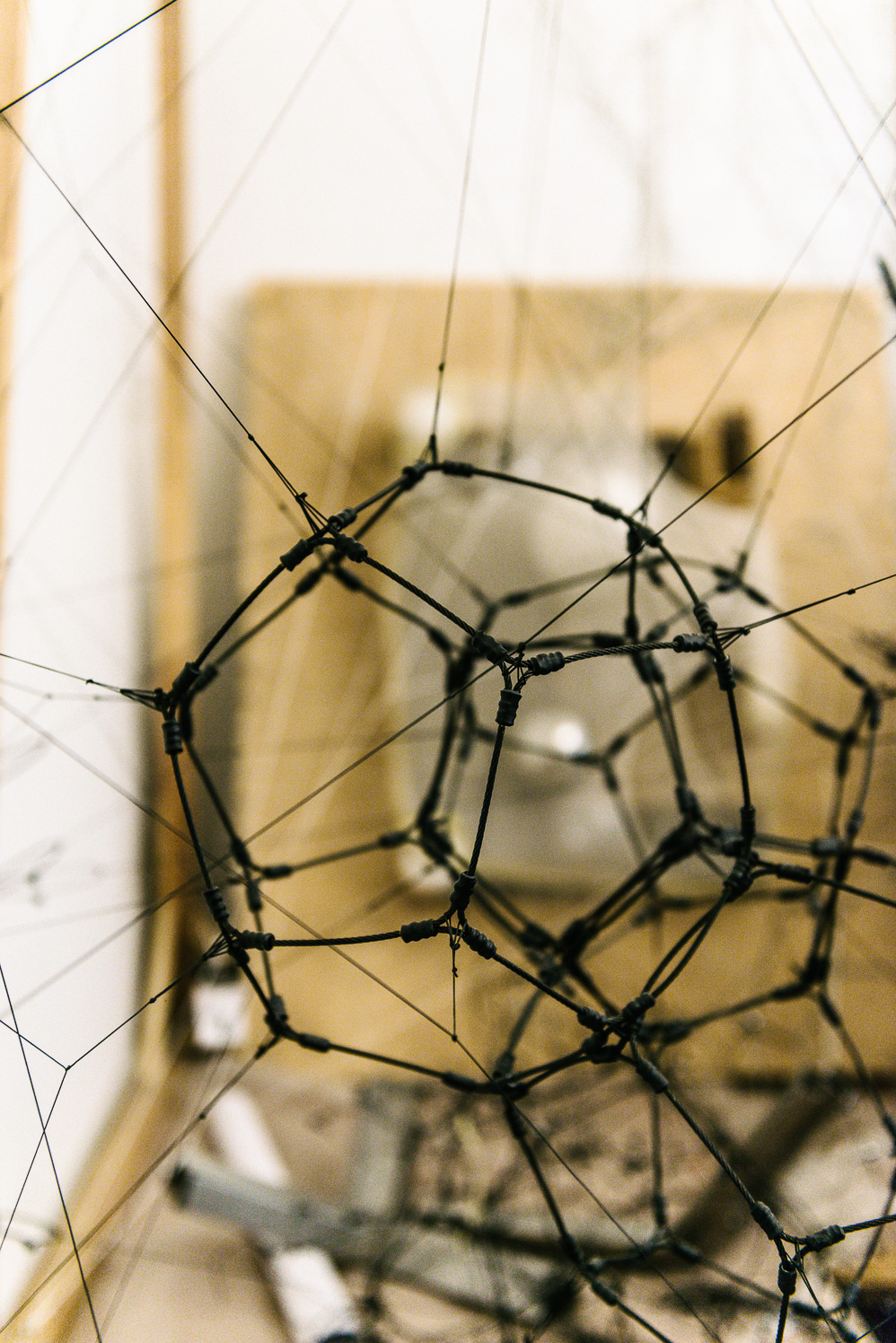

I actually find it boring to talk about chronologies, because I think everything is in everything, meaning many things happen simultaneously and it is often difficult to draw boundaries. But we could say that the preoccupation with spiderwebs started after my show at Hamburger Bahnhof in 2011, or maybe during On Space Time Foam a year later at HangarBicocca in Milan. When I was doing the show at Hamburger Bahnhof, what Udo Kittelmann, the curator and museum director, saw in my models—and for this occasion I have to call them models—was actually also a reference to the social sciences, more precisely the ANT (actor–network theory) by Bruno Latour. This was when my attention shifted and I started reading Latour’s Reassembling the Social. A year later I met Bruno during the panel discussion at HangarBicocca. It was a beautiful conversation about the effects of sharing a space, of bodies moving and interacting, of the dynamic space relations that existed in the installation.

What I also think a lot about is this thing called “focusing illusion”, something Daniel Kahneman wrote about in his book Thinking Fast and Slow. It describes a cognitive bias that has to do with putting too much emphasis on one particular aspect, and not being able to make up an accurate overview of a situation. So while I was already interested in spiderwebs and the way they function, how the web is part of the spider’s body, I was not aware of the whole realm it opens up. Or maybe it’s just that I didn’t notice, because I came from architecture where one deals with the human scale.

-

So the way you treated space in your installations had already been a reflection of how spiderwebs are organized?

While moving through the installation at HangarBicocca, it feels as if the space itself follows you, or as if it becomes a part of your body. You walk through it and while you do so you bend the space. Imagine a bubble of air that reacts to your movements. And when two people come together the bubble gets bigger. So the space will transform according to your position and movement, consequently the position of the other one is modified too. The structure allows you to be in one place or another until you come too close to someone else. I love this image of everyone collapsing in the same hole, because when you get too close, you make a mass, become heavier and heavier, and the side walls get steeper.

“Air became my material of choice. Air and tangible relations.”

-

Did this in fact happen? Was this your original intention to facilitate such a collapsing of the space?

Yes. It’s a way to become aware of the distance you need to take from one another and of how close you can get. It’s called proxemics. I think it was Edward Hall who researched the cultural spaces that exist among people and the way this alters different perceptions of space. For example, if I did this interview with another Argentinian person, we might sit closer to each other, because we share a cultural understanding of space, which is bound to where we come from. So you see, space it not just given, it is a construct deriving from human behaviour.

There is a group of architects that have tried to bring the space back to the human scale. Yona Friedman or Frei Otto, for example. Humanizing architecture means considering proxemics in one’s scale. And I think the arts can contribute to that. For me, it also has to do with the presence of air that permeates every space we live in. Air became my material of choice. Air and tangible relations.

-

What other implications does the humanization of architecture have?

So coming back to Daniel Kahneman and the focusing illusion: All the time we were looking at webs, their architecture and web-like structures, and then suddenly it was obvious—what about spiders? And only then we started investigating how spiders live. But no one actually asked about mosquitos, the poor victims! So that’s the focusing illusion problem for me. We concentrate on something, while all the rest becomes very irrelevant to us. And that just leads to us forgetting, or not seeing how in an ecosystem everything is related. That’s a big problem we have, as human beings. That’s why everyone in the studio is also trying to take on responsibility and together focus on something that alone we could not see. I notice something, you notice something. Together we work on grasping the ecosystem. Art can help us see this multiplicity of scales and phenomena, use a multi-lens to show that we co-exist and share the space with more-than-human beings.

“I find it hard to believe that there will be a point in our evolution where we stop asking where we came from and where we will be living in the future.”

-

What do you think about the current plans of colonizing other planets, like Mars or the recently discovered Trappist-1? Is the idea of leaving Earth something you think of approaching in your work? Or is looking for another space for habitation something we should be critical of?

One approach doesn’t necessarily contradict with the other. How can you not become obsessed watching the stars and imagining things, asking these questions? Where do we come from? Is there life on other planets? I find it hard to believe that there will be a point in our evolution where we stop asking where we came from and where we will be living in the future. We might be living somewhere else, maybe still on this planet, maybe somewhere else. But yes, we also need to be aware of the ethics that come together with this questioning.

A lot of scientists regard the biosphere experiment as an urgent need, since our habitat is very complex and not well understood. Those reduced scale models (like Biosphere 2) often fail due to our technocratic perspective of living systems and our predictions about them. For example, we may know or at least suspect that the reduction of food and space would decrease the sociability of a spider. But in fact, there are spiders, observed in Argentina, that behave in the exact opposite way: they become more social and cooperative upon times of scarcity, and have proven to be much more successful in surviving in the long term.

-

What is it that you are proposing with the Aerocene project? It seems that along with coining the term you wanted to challenge the idea of an Anthropocene that is so prevalent in current discourse.

We don’t know yet what it means. But what we know is that the term is an excuse for us to think of a new epoch that we would be proud and happy to be part of. So far I’m not very happy to be part of the Anthropocene, and we thought that by naming and imagining a new epoch we could change our current ways of acting and working, the ways we are used to doing things. The future will depend on us understanding and acknowledging our own influence on other species and this planet. And how we should better attune ourselves.

With Aerocene, we are by any means trying to understand how we can stay on board on this planet. We know that Earth might be sweeping us away very soon. And there might be other passengers, like the spider, who have been on board since 300 million years building their webs—they do not care if we are here or not. The Anthropocene is always about looking at us, our impact on the planet. With Aerocene, we also look at the sun, at correlations between bodies, planets and stars, and seek different ways of how to dwell on Earth. I think that Aerocene is a lot about different energies and an exchange that constitutes a countless variety of relations.

“What is our nature? Is the planet part of our body or not?”

-

What does that mean in practice?

What we are proposing is this idea of flying with one’s feet on the ground. The first reaction always is: ‘Oh my God, flying—where? At which speed?’ I respond 108 000 km/h, which is the speed of Earth in its orbit.

[Tomás starts unpacking the Aerocene Explorer] This backpack will allow you to experiment with thermodynamic energies of the atmosphere and of the sun, to reconnect with the way we fly with our feet on the ground. It is something very simple. All you need is an inflatable, sunshine and the wind. Once you inflate the black sculpture by running with its mouth open, let it simply sit in the sun, getting heated up, and then it will start to rise by itself.

There is Museo Aero Solar too: a community project which was initiated by a group of people in 2007—and I am proud I took a part in it. It has occurred in more than twenty places around the world. The principle is also simple: you collect many plastic bags together with others, and reuse them by pasting them all together. The envelop will lift up when it gets warm, without fossil fuels. It’s amazing how simple it is. And it is as much about the collective work that is required, as it is about the object itself.

-

Would you say in this respect the Aerocene Explorer acts as an extension to the human sensorium?

I think so. Because, what is our nature? Is the planet part of our body or not? I think it is part of our sensorium. Climate change was discovered because a man was looking at a landscape with the feeling that something had changed, and only then did he come up with a tool to measure that change. There are many scientists who can explain and measure things, but what comes first is always a feeling. Feeling and sensing gives the studio a base to work together with scientists, every collaboration starts with it.

We don’t really aspire to run a true transportation company, but we might be a transportation company of imagination, of thoughts, of feelings, of sensing things differently. Art rarely deals with quantitative means, and we probably struggle a lot to quantify different feelings. At the same time art can be really concrete, too. The level of concreteness and direct engagement that we can reach in the studio also represents a certain responsibility that may excuse me to still take a plane today. Because nowadays it’s not enough to do a painting and believe the world will get better by this.

Thank you, Tomás, for sharing a personal account about your (meta)physical journeys and letting us explore your studio in Berlin. We also thank Ignas Petronis for taking the time and coordinating this interview.

We highly recommend visiting either of Tomás Saraceno’s current exhibitions to experience his work first hand: The group show “Between Spaces” at ZKR in Berlin or his solo exhibition at Haus Konstruktiv in Zurich. Information about “Our Interplanetary Bodies” at ACC in Gwangju, Korea and further upcoming shows can be found on his website.

Did you know that Tomás actually holds the world record for the first and longest fully solar-powered flight? (Video proof here.) If you want to float yourself, check out the Aerocene explorer and calculate your itinerary.

Text:Vanessa Oberin

Photography:Daniel Müller