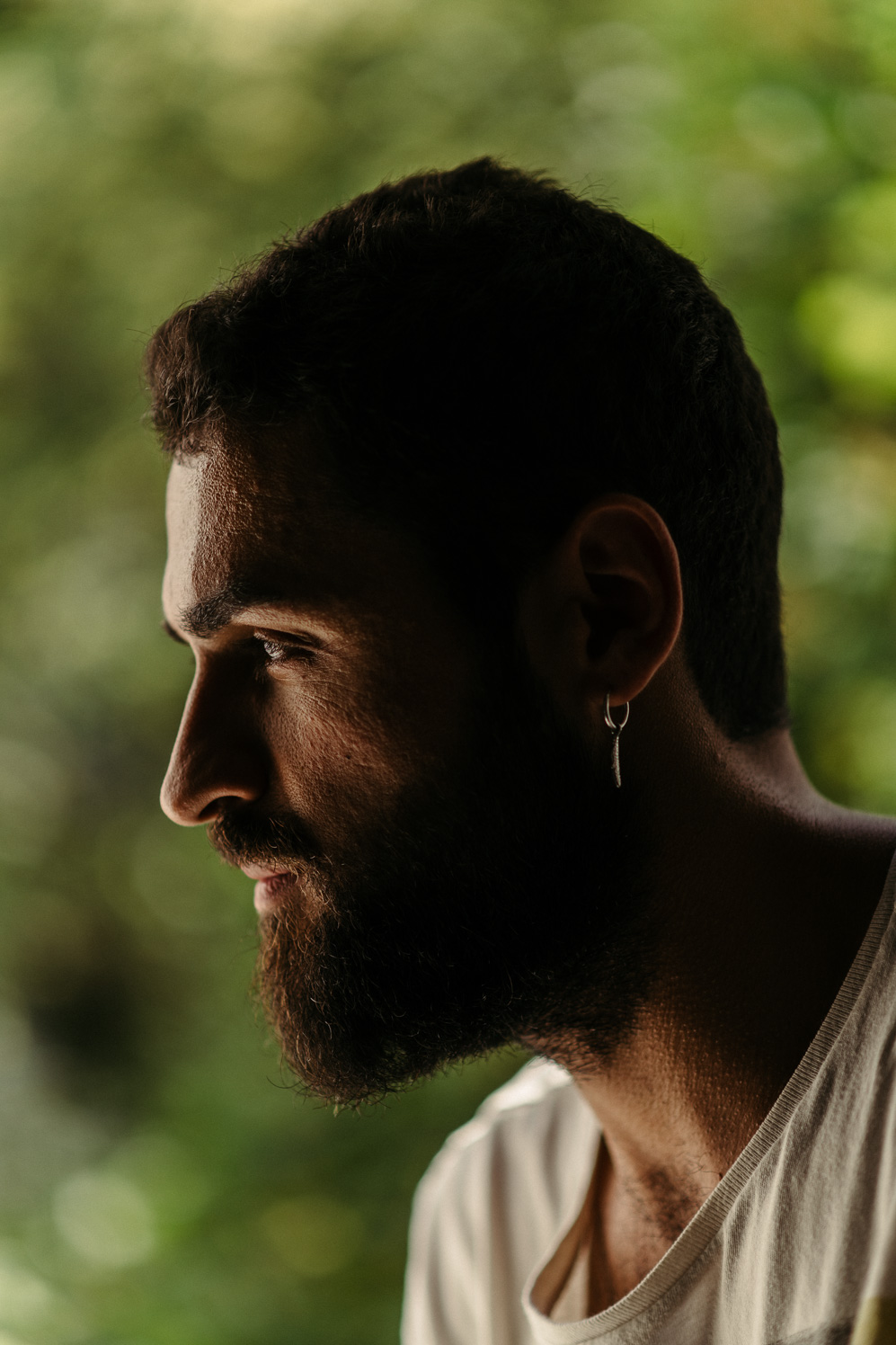

Medhat Aldaabal catches his breath after an improvised performance on the deck of the arts and theater center, Radialsystem V in Berlin.

It was in this exact spot two years ago that the contemporary dancer and choreographer’s first performance of his personal piece Amal took center stage. Amal depicts its four immigrant protagonists’ state of being in-between; between Syria, Medhat’s native country, and a new society in Berlin, his home since 2015. Or, as Medhat calls it, “a completely new world.” His group of dancers were acting out argument scenes between relatives and moments of inner conflict through the dance; their emotions juxtaposed anger and hate with peacefulness, love, and forgiveness. The audience likely ascribed their act to war or crisis. Medhat doesn’t mind such misperceptions, though. “With dance I can say what I want without judgement because my body hears what I’m saying, and I can say it in my language of dance,” Medhat notes.

It’s impossible to untangle Medhat’s professional path from his personal background. Amal is Medhat’s brainchild, both conceptually and choreographically (he co-created it with dancer Davide Camplani of Sasha Waltz & Guests), and encapsulates his artistic development as a contemporary dancer at Sasha Waltz & Guests—a partly state-funded company that involves artists from about 30 countries. Amal was created in 2016 as part of Zuhören (Listening), a conversation format founded by Sasha Waltz addressing artistic strategies with regards to political and humanitarian conflicts. The Arabic term ‘amal’ translates to hope, and as his hope continues to thrive, Medhat knows his dance piece of the same name will continue to develop and evolve. “The fighting becomes less apparent in Amal as it’s progressed. Naturally, if you tell a story several times, it becomes less painful.”

Only recently, Medhat was given the opportunity to focus on just that when his local engagement gained him the fellowship ‘Weltoffenes Berlin’ (Cosmopolitan Berlin) which is given to artists who are unable to work in their home countries. The year-long fund, which required Medhat to apply with his supporting institution, is Medhat’s ticket to learn how to manage himself as a freelance dancer and choreographer—not only his ultimate goal, but the idea behind Sasha Waltz’ motivation to support and foster talent. Medhat compares Waltz to a godmother. “She never treated our relationship like teacher and student; she’s a friend. She has helped me throughout the entire process. I knew she had my back,” Medhat says about their collaboration which includes the teaching of young refugees and joint performances at Zuhören, among them hours of improvisation. “She opens her mind so much to inspire other dancers. If I worked with her for one year just every day, I would learn as much as I would in ten years.”

“People here have more trust in you as a dancer. I never had that before.”

The fellowship has also gained Medhat independence from the job center, an environment and corresponding experiences he and two other male dancers deal with in Come as you are which they created with choreographer Nir de Volff. “I always understood that if I want to share my opinion, there are going to be a lot of people who don’t like it. No problem. I’ll share it in a different way. Dancing is that different way. And it works,” Medhat states. Come as you are’s depiction of Medhat’s everyday reality of living in Germany—a reality dominated by council runs, paperwork, rejections, fears, new encounters, and mental challenges—is physical and intense. It also embodies his transition from a dance scene heavily focused on traditional principles to a contemporary dance landscape—one that, in Medhat’s words, is “full of opportunities, where no dance space is the same.” More importantly, Medhat’s recent creations no longer require him to conform to classical dance movements, or as he calls it, “destroy my body.” Medhat graduated in drama arts from the Higher Institute of Drama Arts in Damascus in 2014, and only in his fourth year realized that he could be a choreographer, a profession he wanted to pursue outside of Syria. “They need someone flexible who can jump, stretch legs, and so on. I don’t have that kind of flexibility.”

Since collaborating with Sasha Waltz & Guests, Medhat translates his ideas, emotions, and experiences into an expressive, eclectic, dynamic, and captivating aesthetic. He has found his platform not only as a dancer, but a choreographer. “I have found the time and space to figure out who I am, how to work, how to move. People here have more trust in you as a dancer. I never had that before,” Medhat says, as he finds his position back on the deck’s dance floor, raising his arms, spinning his body, his feet gently sliding across the grey flooring.

“I believe that we can live through our art, otherwise it makes no sense.”

Medhat’s techniques evolve through breathing, by controlling and not controlling himself at the same time. “You improvise,” he says as he theatrically gestures with one hand, then raises the other to shape the letter M. “If you want to talk about yourself, you figure out how to say ‘hey’ and ‘I’m Medhat’, for instance. You build up small movements, pick them up, and develop them into something else.” Everything else is emotion. “Why do you want to say that you’re here? Because you want attention. What does that mean for you? You may feel insecure. How does your body react? With a movement that you develop with a technique,” Medhat explains.

In Syria, such experiential methods are overshadowed by intricately rehearsed choreographies. The folk dance practice dabke is most common, which comes with a range of synchronized and rhythmic steps, stomps, jumps, and kicks, all guided by the hip. Medhat hasn’t abandoned what he learned in his home country—instead, he incorporates the traditional into Amal by building on movements generated from his hips. “Contemporary triggers something in you. As with anything, if you want a piece to be special to exist in a community, you have to find your own personal way to stand out.”

Medhat also communicates his idea of cultural understanding off stage; he has recently joined Berlin’s Humboldt University to talk about dance as a form of integration. “Everyone is an artist—everyone is crazy, creative, and talented—no matter the technique. You just need to find the right opportunity, time, and place to present your art to then see if the audience believes, accepts, understands, or even loves it. Just do something real, whatever it is, and you will send a message. And it’s not important if your legs are up or down, you jump or not, your arm is tense enough or not.” Medhat understands his fight for attention as one that involves training, gaining experience, and developing ideas. “It’s not really fighting for ‘listen to me’—it’s ‘please stay with me’,” he says.

Moving forward, Medhat aims to open more people’s eyes on issues that not only concern him. “I understand movement as an exchange, but it also embodies change. The way I deal with people is changing; I’m more open, more acceptable, and more understanding.” All that has developed with time. He was even at peace with the idea of giving up dancing professionally. “I always think about the worst things that could happen. If I have peace with the worst things then whatever happens will be okay. But I believe that we can live through our art, otherwise it makes no sense.”

Medhat Aldaabal is a Syrian dancer and choreographer trained in drama arts. Since 2016, he has collaborated with Sasha Waltz & Guests, a Berlin-based company dedicated to the exploration of contemporary dance and theater and creating exchanges with cultures from all over the world.

Aldaabal is a fellow of the programme Weltoffenes Berlin and the co-creator and dancer of Amal and Come as you are, a choreography by Nir de Volff that has been shown at Dock 11 and on tour. Amal has been shown at the arts center Radialsystem V in 2016 and 2018, at Berlin’s Sophiensaele in 2017, and on tour in Karlsruhe and Erfurt. Together with percussionist Ali Hassan, he regularly hosts the Dabke Community Dancing workshop to introduce people to his culture.

Text: Ann-Christin Schubert

Photography: Robert Rieger