In 1964 a series of five painted canvases were installed on the top floor of a Cambridge building belonging to Harvard. The works in question were cohesive rectangular forms saturated in dark colors by the artist Mark Rothko, commissioned especially for the university.

Almost as captivating as the Rothko Murals, apparently, were the views from the adjacent windows out onto the city—thus the curtains were often left open and the light allowed to stream freely into the penthouse dining room.

It doesn’t take a scientist to guess the level of deterioration to these works over several years of exposure to bright light. Even to an unobservant eye, it was a radical shift from their original state. But it does, however, take a conservation scientist—a whole team of them, in fact—to put it right. At the Harvard Art Museums in Cambridge, Massachusetts, this has become known as one of their spectacular restoration projects. Using noninvasive light technology, a digital projection seemingly restores the vibrancy of the murals, without leaving a single mark.

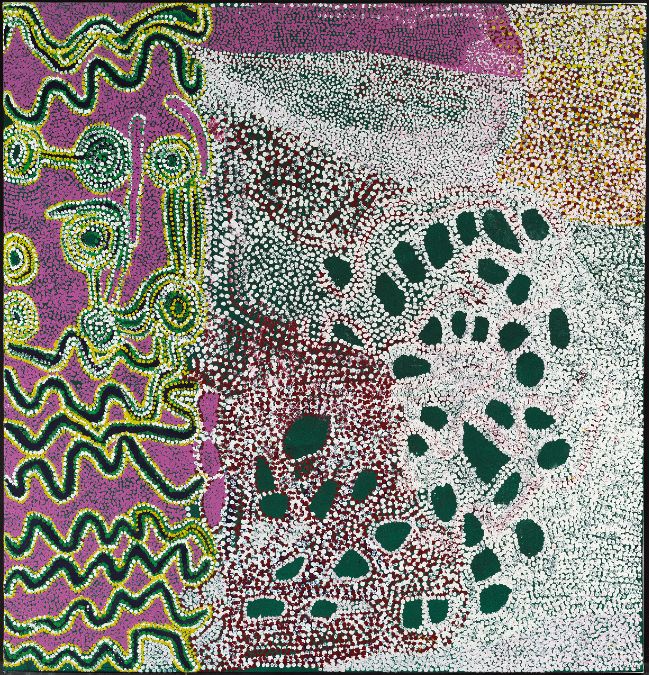

“This was a place of pioneering research, and is a place where new research and approaches to conservation still happen: The Mark Rothko Harvard Murals project, and an analysis of Aboriginal bark painting materials are two recent examples,” says Narayan Khandekar, director of the Straus Center for Conservation at Harvard Art Museums. Sitting in his fourth floor laboratory, the Australian conservation scientist is selecting pigment samples to be displayed in the Art Study Center. When we think of color pigments, most of us will think of red, orange, yellow, perhaps even Yves Klein blue or VantaBlack will spring to mind. But how about Stuart Semple’s Pinkest Pink? Or the lost, forgotten, and rediscovered 17th century lead-tin-antimony yellow? These are just a couple of examples from thousands of color pigments Narayan works with in his role. Newer selects he’s adding to the collection include ochres from Australia he personally dug up and pigments and dyed yarn samples from the Zapotec weaver Porfirio Gutiérrez.

When Narayan isn’t digging up golden ochre from Australia’s Arnhem Land coast, he can be found here at Harvard researching and better understanding the materials and techniques used by artists through the ages. Narayan likens his practise to that of forensic science—but in place of a crime scene there is a rare work of art. In essence, Narayan wants to discover not just when a painting was created but to decipher exactly what it was made of and how it was done.

We caught up with Narayan in his laboratory for art to discuss conservation, preserving Rothko murals, and the use of technology to future-proof fine paintings.

-

For those unfamiliar with the Harvard Art Museums, what does it mean to be the Director of the Straus Center, the world leader in fine arts conservation, research, and training?

The Straus Center has a long history in the field of conservation. Francesca Bewer wrote about it her book, A Laboratory for Art. The first scientist in a U.S. museum, Rutherford John Gettens, was employed here; George Stout, a conservator and researcher who developed the first systematic condition report, worked here before going on to be one of the Monuments Men and later director of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Edward Forbes established the field of technical art history here. Many of the publications they produced are still important reference resources and have not been bettered, such as Gettens’s and Stout’s Painting Materials: A Short Encyclopedia.

This was a place of pioneering research, and is a place where new research and approaches to conservation still happen: The Mark Rothko Harvard Murals project, and an analysis of Aboriginal bark painting materials, to name two recent examples. Much of our work is dedicated to the exhibitions we hold in the Harvard Art Museums galleries; to understanding the materials and techniques of artists; to ensure the best storage and display conditions for the collection; and to teach and disseminate our research to students and colleagues. -

What are you currently working on?

We have just retrieved a very fine painting of Philip III of Spain by Juan Pantoja de la Cruz from storage. The painting is from the early 17th century and is unlined, which is very, very rare and it has a very early, if not original, strainer. We will investigate the painting and determine where in the chronology of the artist’s work our painting lies and how it relates to other versions in collections like the Prado.

-

Tell us about your background: Where did you grow up, where did you study, and were you always interested in art and chemistry?

I grew up in Australia, mostly Canberra and Melbourne. I studied chemistry at the University of Melbourne where I obtained my PhD in organic chemistry (marine chemistry). I then studied painting conservation at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London. I found I had a knack for chemistry and so it seemed natural to study it at university. When I was doing my PhD, I found that I was more and more drawn to art, and wanted to find a way to combine the two, which was why I turned to conservation.

-

Can you tell us a bit about your experience in Northern Australia when you were surveying traditional Aboriginal bark paintings?

The Harvard Art Museums had an exhibition called Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia, which was on display from February through September 2016. In association with that exhibition we carried out the first-ever large-scale survey of traditional bark painting techniques. The findings are included in the catalogue, and challenge some of the established conventions about Aboriginal bark paintings. We traveled to art centers at the Top End of Australia and talked to artists about how they painted, and how their ancestors painted. We traveled to ochre deposits with the artists and collected pigment, with their permission. Remoteness is a relative term, and from my perspective these were some of the most remote locations I could imagine. The artists were so open and welcoming to all my questions. It was an incredible experience in a part of the world I had never been to before. When I asked Gordon Pupungamirri, a senior artist from the Tiwi Islands, what I could do in return for all the help and kindness he had shown me, he said: “Tell the world!” which I have been doing as often as possible.

The Straus Center labs on the fourth and fifth floors of the Harvard Art Museums: Over 2,500 pigment samples are displayed in these glass cabinets along with a large collection of binding media, varnishes, and resins.

-

The fields of science and art don’t often correlate. As a conservation scientist, did you always wish to specialize in the field of art preservation?

I think there is an artificial divide between the humanities and the sciences, and I am happy to straddle the two as I am comfortable in both areas. I think the biggest challenge is to be able to present scientific information to curators who have not thought about science since high school, and presenting art to scientists who have maybe never been in a gallery. It’s important to be bilingual to break down the barriers between colleagues so that they can appreciate the other point of view.

When I was studying in London, I found that my niche was as a scientist interested in the materials and techniques of artists, and colleagues at the National Gallery, Tate, as well as the National Gallery of Art, D.C. encouraged me to pursue it as a career.

-

You’ve worked at universities and museums in London, Cambridge (England), Melbourne, Los Angeles, and now Cambridge (Massachusetts). What inspires each move?

At the beginning of your career, you spend time working out where your skill-set best fits, which entails moving around. I have learned an enormous amount at each place I have worked and am grateful for all the experiences I have been exposed to. Each move has been to take on bigger challenges and stretch my thinking and skills. I have been lucky to be able to land in a place, which in many ways has been the starting point of the field, and to be able to make contributions by standing on the shoulders of these giants.

“By understanding the materials used by an artist you are getting an insight into the artist’s thinking.”

-

Tell us about your latest book, Collecting Colour. How did it come about?

I was invited by the Sikkens Foundation to give a lecture to introduce the presentation of the Sikkens Prize to Hella Jongerius in March 2017 in Rotterdam. They wanted my lecture to be published in time for the event so I worked on it with the very talented people at ArtEZ Press. They produced a beautiful and informative publication. The book covers the history of the Forbes Pigment Collection, new additions, and current uses of the collection.

-

In your experience, have you noticed an increased interest in culturally relevant colors and the wish to preserve them?

Artists have been interested in the emotions that colors evoke, and have explored that for a long time. Gauguin, Kandinsky, and Marc are three artists who all explored the emotional meaning of color. In reading about this aspect of their work, it is apparent that there is no universal correlation between color and emotion; it is an individual experience. There is an undergraduate investigating her own synesthesia at the Harvard Art Museums and the metaLAB (at) Harvard this summer, which tells us that the connection between color and feelings is an ongoing fascination.

-

What excites you most about examining paintings and painting materials?

Every artist I have met cares enormously about the materials they use. The materials are fundamental to the practice of making art. Every work of art is made through a series of decisions. By understanding the materials used by an artist you are getting an insight into the artist’s thinking. Understanding the thinking that goes into making a work of art excites me a great deal. It’s a different perspective than what one normally thinks of, but no less valid.

“One rare pigment is Mummy, which requires an Egyptian mummy. It would be difficult to make synthetically as it uses asphaltum, which is itself a complex material of geological age.”

-

How do you use match color pigments to works of art? And is this one way in which a piece can be deemed authentic?

A painting starts changing as soon as it is finished. The colors change, the medium cracks, and so on. When we restore a painting, we are matching the current condition of the original paint. Also, any restoration work we do has to be reversible, and is separated from the original by a layer of varnish. We do not have to use the same pigments as the original painting, but simply match the color, so that you can enjoy the painting without being distracted by damages.

-

From your experience with fine paintings, did artists take huge risks with toxic pigments in order to pursue their chosen hues?

Very much so. Lead white is one of the most ubiquitous pigments, and we all know how harmful lead is. Artists have used pigment with lead (red lead, lead white, minium), mercury (vermilion, cinnabar), arsenic (emerald green, orpiment, realgar), cadmium (cadmium yellow, cadmium red, etc), cobalt (as a drier, Cobalt blue), and the list goes on. Every time an artist licked the tip of their brush to get a good point, they were taking a risk.

-

Can you tell us about some of the rarest pigments? And can these ever be recreated synthetically?

One rare pigment is Mummy, which requires an Egyptian mummy. It would be difficult to make synthetically as it uses asphaltum, which is itself a complex material of geological age. It has not been produced for around a hundred years. Another rare pigment is ultramarine, which was ground from lapis lazuli and was as expensive as gold and had to be mined in Afghanistan. However, in 1826, a synthetic version was manufactured, which changed the value of the color.

-

In layman’s terms, can you explain how you use science to understand and study great works of art?

We use scientific instruments to identify the materials an artist uses. For example, we use infrared and Raman spectroscopy to identify a pigment. We collect a spectrum and compare it to a library of standards, and then match up the peaks. We can use gas chromatography to identify the medium, determine if linseed, walnut or poppy seed was used, and if additives like resins or other oils were added. It’s a lot like forensic work, but we are looking at a work of art, and not a crime scene. We want to understand what a painting is made of, and how it was made.

-

The physical and chemical makeup of a work of art can contribute to its own deterioration. With this knowledge, are new painting materials adapted for improved wear over time? And if not, is this something you’d like to see?

I don’t think it is our place to tell an artist what to use or how to use it; if an artist uses food products, or bodily excrement, or commercially canned material, or hair, it is our job to work out the best way to care for that work of art. We never sit in judgement of the medium. We are happy to offer advice if asked.

I know paint manufacturers care enormously about their products, and companies like Golden Artist Colors and Gamblin Artist Colors have worked closely with the conservation community to produce the best possible paint.

-

Tell us about your work lab: Does it really house over 2,500 different color pigments?

The Straus Center labs are situated on the fourth and fifth floors of the Harvard Art Museums, with glass walls that overlook the interior courtyard and allow the public to see in. The pigments are stored in glass-fronted cabinets and on the fourth floor is my lab (the analytical lab). Yes, we do have over 2,500 pigment samples. We also have a large collection of binding media, varnishes, and resins that are also displayed in the cabinets.

“Pigments are used and forgotten about all the time, which means there are lots of discoveries yet to be made.”

-

Many one-of-a-kind pigments each tell their very own story. Do you have any favorite stories you’d care to share?

I like the story of lead tin yellow. It was the predominant yellow up until about 1750. It disappeared from use, possibly replaced by Naples yellow. It was rediscovered in 1940 by researchers at the Doerner Institut in Germany. Another pigment used in the 17th century by Orazio Gentileschi was lead-tin-antimony yellow (see The Lute Player in the NGA), which was rediscovered by my colleagues Ashok Roy and Barbara Berrie in 1998. The reason I like these stories so much is that they tell us that pigments are used and forgotten about all the time, which means there are lots of discoveries yet to be made.

-

How is technology (the use of light or computer algorithms, for example) an integral part of the restoration process?

The five panels that make up Mark Rothko’s Harvard Murals had been on display in high light levels in the 1960s and ’70s in a university penthouse dining room. They became faded in an uneven way and the cycle no longer worked as a single unified work as the artist intended. The delicate, unvarnished matte surface of the Rothko murals meant that we could not restore them in the traditional sense by applying paint, as it would be irreversible, and it would cover the artist’s original paint. We decided instead that we could control the light that is shone onto the paintings so that it compensated for the lost colours. To do this we had to work out what the murals’ colours originally looked like, which involved the university of Basel and the expertise of Prof Dr. Rudolf Gschwind to digitally restore Ektachromes taken of the paintings in 1964. Then we worked with the Camera Culture Group of the MIT Media Lab to write software that would allow us to calculate and project the right colours, pixel by pixel—over 2 million pixels per painting—using InFocus widescreen short throw projectors that were carefully aligned with the paintings. This all required a great deal of programming, and as we were doing this for the first time, a lot of perseverance and support to see the project through. This project was only possible because the technology was in the right place, and the right group of people were all together at the same time, and the Harvard Art Museums had the foresight to invest in this groundbreaking work.

-

What future tools would you love to aid your work?

I am interested to see what augmented reality can yield as a way to restore museum objects. This is technology that is rapidly developing and very exciting.

“Forty years ago no one wanted to see cracks on a Mondrian, now these are seen as a sign of its authenticity.”

-

Where do you draw the line with preserving and restoring works of art? Is there a point where you need to let go and allow for the natural patina of time to develop or is the aim always to try and keep a work as close to how it was when originally painted as possible?

Patina is something that changes with fashion and with the age of a painting. Forty years ago no one wanted to see cracks on a Mondrian, now these are seen as a sign of its authenticity. When we restore a work of art we want to keep the good changes (these are called patina) and get rid of the bad changes. The trouble is that the definitions change all the time. In the museum world we are very cautious and do not make decisions about a work of art lightly. I have a thought that people see a work of art, when it’s new, in a human timeframe in the same way we look at ourselves, so that we do not want to see signs of age until an object is beyond late mid-life, then it becomes acceptable. It’s part of human narcissism, where we project our own values onto the things around us.

-

Outside of art preservation, do you ever collaborate with the fashion and design industry or new contemporary artists?

I have been working with Jonathan Olivares, a Los Angeles-based designer, who has been using the pigment collection as inspiration for the twill weave fabric on a twill weave carbon fibre daybed. We have had visits from fashion and sports companies who are fascinated with the colours and their origins.

-

Can you tell us about any milestone projects?

Every time we complete a project we publish the work in a catalogue or in an academic journal. I am the author of over 60 publications, which is another way of saying that we just keep on doing what we do, and we love doing it.

Maybe the most important work I have done is to help establish a post-doc fellowship for scientists who want to work in a museum. The fellowship provides the training and support needed to change career paths, and provides an established way into museum work for young scientists, something that did not exist when I was starting my career.

We were thrilled to be invited into the Harvard Art Museums laboratory for such a fascinating insight into the Forbes Pigment Collection and Narayan’s work in art conservation.

If Narayan’s role has whet your appetite for further research, check out Harvard Art Museums’ most recent exhibitions on their website. And learn more about how their art conservators and curators work together with this insightful digital tool. More information on Narayan’s book, Collecting Colour can be found here.

Interview: Andie Cusick

Photography: Webb Chappell