Ahead of her first solo show in Germany, the artist speaks about rebelling against her strict religious upbringing, drawing inspiration from a childhood spent in front of the television, and the importance of laughing in the face of adversity.

When eating out at restaurants, Jessica Westhafer’s father used to hand her napkins to draw on. “Draw that person over there. I’ll do the same. Let’s see how realistic we can be. At the end, we’ll decide whose picture is better.” An electrician by day, he was also a talented draughtsman who cultivated his daughter’s love for art, taking her to copious galleries during their summer vacations to New York and Washington DC. “I remember going to DC for the first time and seeing a Van Gogh painting in a gallery,” says Westhafer. “Me and my dad sat in front of it for over half an hour, in awe of what we were looking at.”

Despite having a close relationship with her father as a child, Westhafer, now 30-years-old, hasn’t spoken to him since she was 18, when she decided to leave the strict religious community of Jehovah’s Witnesses she was born into. “My whole family cut me off. It’s a very conservative and exclusive religion: you’re not allowed to celebrate birthdays or Christmas, participate in sports, or even associate with people outside of the organization,” she says. Westhafer, however, did attend a public school, as her parents didn’t have the time to educate her at home. Here, the art classroom became a rebellious space, and she made a diverse group of friends—who she describes as “punk kids”—who encouraged her to question the way she was being brought up. “They taught me how to be a human: how to be an individual and to think for myself,” she says, reminiscing about sneaking out with them at night to go to DIY music shows. “My friendships were a lot about music in those days. We listened to a lot of My Chemical Romance, Panic! at the Disco, and other shitty emo stuff. It fueled the anger within me.”

Several Jehovah’s Witness doctrines prompted Westhafer to leave the organisation, a big one being the fact the religion doesn’t believe in going to university. “It’s something that’s looked down upon because you’re surrounded by so many worldly people from outside of the religion,” she says. “I did it anyway: I took out student loans and went to the University of Arkansas to study art. I found friends who became my family, and I just threw myself into my work.”

After her undergraduate degree, Westhafer returned to her former high school to teach, hoping to “give back” to her former art teacher who had greatly encouraged her to follow her passion. After two years, she realised it wasn’t for her. “I wasn’t done learning myself. I realised I wanted to pursue painting full time. It’s what I love, I knew I should be doing it everyday.” As a result, Westhafer headed to Indiana University to complete their MFA Painting programme. Here, she had time to experiment and figure out who she was as a painter. “My undergraduate programme was very traditional, and taught me to paint really realistically from my surroundings. At IU, I had the chance to break free from that.” For Westhafer, this primarily meant allowing her interests in 90’s video games, trash TV, and cartoons which she had previously kept secret from her art professors, to influence her work in the studio. “Painting has always been viewed as the pinnacle of art. It can seem very elitist because of its lineage through art history,” she says, recounting how she was rebuked during her undergraduate for her work being too illustrative, and told that if she was interested in illustration, she was at the wrong school. “Cartoons are seen as low brow and just for kids. Some people think the two things can’t mesh well together. I think they can.

“Returning to cartoons as an adult has really made me appreciate the dichotomy between their childish levity and the darkness that lies beneath the surface.”

During her MFA, Westhafer’s depictions of figures and characters became “loose, wonky,” and surreal, just like the programs she was watching. Her thematic concerns also shifted. “Returning to cartoons as an adult has really made me appreciate the dichotomy between their childish levity and the darkness that lies beneath the surface,” says Westhafer. “There are so many things in cartoons that I missed when I was a kid, such as Rugrats commenting on the challenges of parenthood, or the penis-like spire on the castle in Disney’s The Little Mermaid. I think my work functions in the same way. Sometimes it can appear really whimsical, but then you can look at it and realise there’s some darkness in it too.”

Westhafer’s time at Indiana University came to an unconventional end last summer, as she graduated amidst the global coronavirus pandemic. “Leaving graduate school is a big transition. We all feel like we never got closure from that experience because there was no end mark,” she says, lamenting not having a physical graduation show. “The pandemic has bonded everyone, because we can all relate to what each other is going through: being stuck inside, losing jobs, and losing family members. In this context, being sad about not having a show seems like playing the world’s smallest violin: we feel shame for feeling sad, there are so many other larger issues at stake.”

Despite the unstable state of the world, Westhafer decided to relocate to New York City upon graduation. “There’s nothing going on right now: the world is literally frozen because of the pandemic. It seemed like the worst time, but also the best time to go full force and try it out,” she says of her move. Wanting to be in a “place where art thrives, where [she] could go and see work excessively,” Westhafer has based herself in Bushwick, Brooklyn. A 45-minute walk away from Manhattan’s vibrant gallery scene, the neighbourhood is also an art hub in its own right. “I’m a short walk away from other people’s studios, there are great coffee shops, and there are nice little parks. It’s a bit dirty compared to the beautiful Midwestern countryside I lived in previously, but I love it.”

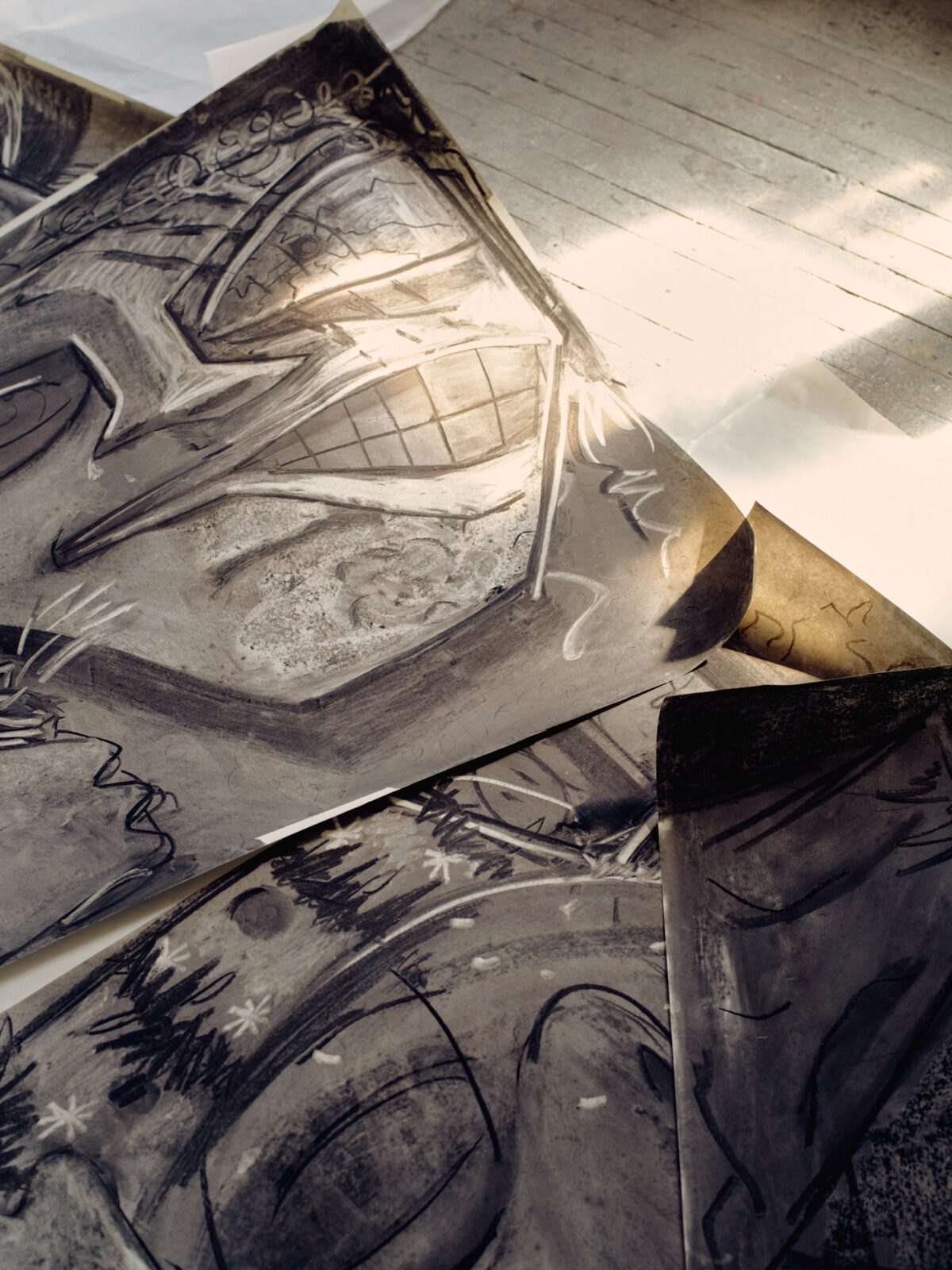

Moving to New York, however, hasn’t come without its challenges. Westhafer’s first week in the city in particular put her through her paces: her car was impounded and her apartment flooded. But rather than give up and leave, Westhafer channeled these experiences into her work, creating Mind Over Matter, which will open at Berlin’s Duve Gallery as part of Gallery Weekend 2021. The artist’s first solo-show in Germany, Mind Over Matter is a series of eight surreal oil paintings in which characters are forced to walk perilous tight ropes while attacked by violent crows, sink in rowing boats, and cry over large bowls of ice cream as they try to eat them with comically small spoons.

Despite being inspired by trying experiences, the artworks are far from despairing or helpless. Instead, they celebrate the power of the human spirit to tackle seemingly insurmountable obstacles. “I wanted to depict how, during this time, I felt powerful because I was overcoming all of these difficult things,” says Westhafer, who also hopes that, while somewhat autobiographical, Mind Over Matter will resonate with a wide audience. “We all have desires, we all have fears, and we all feel pressure. I want other people to be able to view the work and relate to it in their own way.” To achieve a sense of universality, the artist has painted most of her figures with their faces turned away or hidden. This is a new approach she has adopted since moving to New York in order to place greater emphasis on archetypes and emotions rather than her individual characters. “For a long time, the figures in my paintings were me,” says Westhafer. Her graduate collection, About A Girl, for example, drew on memories specific to her rebellious adolescence, causing mayhem with friends who opened her eyes to life beyond the strict religious community she was born into. “Now, the characters in my paintings are becoming more like archetypes and their genders are ambiguous. They’re almost not people at all, they are like the spirits of the paintings.”

Considering the past year the world has endured, in which people across the world have felt overwhelmed by having to adapt to an alternate reality, it seems likely that visitors to Duve Gallery will be able to empathize with Mind Over Matter, and the way in which Westhafer’s figures fight for survival amidst harsh landscapes. It also seems likely that they’ll raise a smile: with their bold colors and fantastical, melodramatic narratives, the paintings are also full of humor and lightness. “When you go through hard things, you have to laugh a little bit to get through it,” says the artist. “I feel like that’s been the story of my life. In the face of anything that I’ve had to go through that’s a bit tragic, or difficult to deal with, I’ve just decided to laugh at it and push on through.”

“When you go through hard things, you have to laugh a little bit to get through it.”

Jessica Westhafer is an artist based in New York City. Having recently graduated from Indiana University with an MFA in painting, she will be making her German debut with her solo show Mind Over Matter at Duve Gallery as part of Gallery Weekend 2021. For more information about her work, check out her website or her Instagram account. Or, for more Friends of Friends stories from New York City, click here.